10th year of Syrian civil war: Schooling and psychosocial issues of syrian children in Turkey

Опубликована Окт. 1, 2021

Последнее обновление статьи Авг. 19, 2022

Abstract

Various studies claim that war has devastating effects on the psychological well-being of its victims. Such conflicts destroy not only cities and their infrastructure but also the established systems; such as the schooling system. In the wake of such destruction, millions of children are displaced and find themselves apart from their homes and their schools. Their attempts at accommodating themselves with the host communities are not easy, given the immense trauma they experienced. The resulting psychological and social problems make it more difficult for these children to fit in. The disruption to their education is yet another factor that affects their attempts at fitting in. The current paper aims to present a literature review focusing on the issues faced by child victims of war and conflicts. From their most apparent needs to the more subtle ones, this paper aims to evaluate the overall status of Syrian children in Turkey. This paper investigates the abovementioned issues by rewieving the previous literature with the help of the both quantitative and qualitative work from international NGOs and researchers. Although a large number of studies on the topic have been conducted, the majority of them focused on the current and short-term psychosocial effects that children face. However, there is much work to be done to prevent the long-term effects of the same.

Ключевые слова

Psychological well-being, education., Syrian children

INTRODUCTION

Turkey has witnessed a progressive increase in the migrant population throughout the last decade. Migrants are usually displaced from their homeland as a result of armed conflicts, politics, or economic crises. The European Commission (2016) defines the term 'migrant' as encompassed within a large spectrum. In a global context, any person who resides in another country for more than a year is a migrant irrespective of the purpose of their stay. In 2011, a devastating civil war broke out in Syria resulting in millions of Syrians losing their homes. In April 2021, more than 3.6 million Syrian people are under temporary protection, according to recent data from the Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM, 2021). Almost a third of this population is subject to compulsory twelve-year education at the moment. The Turkish government and other international organizations are continuously establishing opportunities for Syrian children to procure formal education and quality schooling. Notwithstanding the intensive efforts put forth by the Turkish Ministry of Education, an overwhelming 50% of these children are not utilizing formal education.

Parents from war-torn countries seek a safe environment for themselves and their children. One of the most vital interactions between migrants and the host community is through a child's schooling. Education is a critical element when it comes to integrating into a new society. A large number of migrant children attend institutions providing formal education, and they do so, from the kindergarten to the university level. Learning the language and culture of the host community from an early age is advantageous to migrant children (Yavuz and M?zrak, 2016). With the help of language and a basic understanding of the culture, children can help their parents navigate the differences between their own culture and the host community by acting as a cultural mediator. Consequently, migrant parents would benefit from their children as they attempt to integrate with the host community. Modern Turkey was founded as a nation-state and a successor of an old empire where minorities were allowed to preserve their own culture, language, and education system. Setting up a foundation code that requires and expects to melt different cultures into one single identity was ubiquitous at the time. We need a new solution to a historical event that would hardly ever happen any other time.

Considering that a contemporary worldview is widespread now, the authors need a more persistent political approach to harmonizing the recent migration waves.

METHODOLOGY

In order to investigate the role of education in facilitating the integration process of migrants, it is pertinent to make changes to the existing education system. There are but a few in-depth qualitative studies conducted on this topic.

Despite the efforts made by the Turkish education system including Syrian students, only a minuscule number of studies on the same were published in the last five years. A literature review summarizes and assesses the numerous writings regarding a spesific subject (Knopf, 2006). A systematic review of the literature has been carried through 29 articles. Therefore, the authors aim to present a literature review to evaluate the research findings at hand and to further pave the way for more qualitative and quantitative studies.

RESULTS

After the conflict emerged in Syria, Turkey has declared an open-door policy to anyone in need. Initially, the migrants in Turkey was thought to be short-term guests. Therefore, fewer precautions were taken in educating migrant children.

Interim plans were put in place until the understanding of the situation changed. It is believed that even if the conflict were to disappear in the future, most migrants would prefer not to go back to their country of origin. This could be because of the rich opportunities in the host country or because of the drastic change their country of origin has undergone post-war/conflict (Seydi, 2014). When Syrian migrants arrived in Turkey for the first time, policies to introduce a holistic formal education to migrants were initiated. The idea was the migrants would be empowered enough to continue their education back in their own countries after conflict ends. Therefore, their education was tailored according to the Syrian national education system. The main purpose of this was to make sure migrant children did not fall back on their education as compared to their peers back in their country. Unfortunately, this approach was ineffective and an attempt at a permanent solution resulted in the construction of Temporary Education Centers (TECs). TECs aims to provide formal education to migrant children in their native language (Dillio?lu, 2015). TECs were set up in camps given the large number of children living outside these camps. Consequently, many children were deprived of the chance at formal education, a fundamental right according to Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948).

Historically, Turkey has essentially experienced a domestic migration with some communities unable to speak Turkish leading to problems in integrating and harmonizing with the host communities. The education system did not provide satisfactory results, however, the newer generation showed better academic results than the previous ones. Previously, lower academic success and confidence in migrant students who have attended courses in the official language was reported (Ayd?n and Kaya, 2017; Atac, 2019). It is also important to note that the psychological impact of the civil war. It resulted in most of them experiencing trauma. In other words, Syrian children are more likely to face a wide range of psychological problems compared to their peers. A report from the Migration Policy Institute shows that 6 out of 10 Syrian children in camps suffer from trauma, ten times more than their peers’ average in the world (Sirin and Rogers-Sirin, 2015; Visentin et al., 2017). Children are the most vulnerable victims of this crisis. Therefore, it is necessary to facilitate beneficial psychosocial support to impede long-term hazardous outcomes of the war (Sirin and Rogers-Sirin, 2015; Visentin et al., 2017). The study from Migration Policy Institute points out early insights and needs which makes it unique in 2015 and can be considered as a fundamental work on the issue. Thus, this study is going to examine and analyzing the current status of the problem by evaluating newer studies and sources.

As the years passed and the approach to migrants have changed, authorities have decided to deliver comprehensive education in Turkish and introduce other projects that would include migrant children in the Turkish education system.

As of this point, the authors will evaluate how this process was accomplished and the solutions that can be suggested to provide better education opportunities for Syrian children (Çelik, 2018).

Landing in a new environment: Condition of Syrian children in 2021

Three phases of migration have been reported since Syrian migrants began fleeing the warzone. Firstly, there is an attempt to flee the conflict zone and find a temporary sanctuary. Then, an attempt is made to legally seek asylum in the host country and temporary accommodations in camps. Finally, a residence is established in the host country as they try to accommodate daily life in a new country. During this phase, children should not be separated from education opportunities. They can benefit from formal education in different ways such as learning the language, getting psychological support, integrating into the host community commences after settling in a place (Atac, 2019; Visentin et al., 2017). Younger migrants have an advantage in that they might not be as affected by the culture shock in a foreign environment. Besides, schools may act as a buffer for the children suffering from traumatic memories of the events back home. In addition, they can build personal relations with others and get peer support.

What is social integration? Why is terminology important?

The authors need to outline some of the essential terminologies to make a better understanding for readers. Therefore they would like to explain them to a particular extent in the upcoming sections. Social integration is the activity of individuals or groups of people by establishing a social system with harmony to be close to a larger and broader group and be members of that group. According to the United Nations Research Institute For Social Development (1994), this term brings different meanings to mind, including positive and negative perspectives. When thinking positively, one might imagine it as an effort to include all people socially and develop a humane society. This is a significant paradigm today when policies regarding migrants and refugees are set. Also, there is another perspective that may sound sensible for some. Understanding integration as forced homogeneity is not very common but essential thinking to address issues in migration. Finally, one last perspective between them is neutral and gives no more attention to the word than its dictionary meaning.

Discrimination and, as a consequence, social isolation are two essential terms important to this topic. A child may feel discriminated against when threatened, insulted, or bullied by other children at school. Discrimination has debilitating effects on the emotions of migrants. As a consequence, children will experience social isolation by withdrawing from society (Weichselbaumer, 2016). This two-term independently make it essential to ask research questions about the effects of discrimination on young Syrian children attending school or kindergarten. The preventative and inclusionary school environment we will cover later in this paper has paramount importance before spending another ten years losing almost a generation. In addition to discrimination, there are few other threats to Syrian children’s integration. Harmonization is usually used by Turkish policymakers and social workers instead of integration to facilitate an empathetic approach respecting the guest's original culture.

Needs in schooling of Syrian children

Children have a wide range of emotional and social needs to be met. It is crucial to address these needs with persisting stressors like civil war and the fight for survival. As such, it was an arduous task to meet these needs at the beginning of the crisis. Moreover, most children and parents could not speak any Turkish at all. One solution to this issue comes from Gay (2018:259), who points out the importance of culturally responsive education and clarifies the importance of awareness about past experiences raised by teachers while teaching refugee children. This should be the epicenter of education, including students with different mother tongues, cultures, religions, and ethnicities. Although the teachers may not have sufficient experience and resources to create a culturally sensitive classroom environment, a comprehensive project called PIKTES aims to teach the Turkish language to Syrian children of school ages (Shaherswasli et al., 2021).

Approximately ten thousand Turkish teachers were assigned to integrate almost a million students into the Turkish education system. This project is instrumental in bridging the gap between students' previous and current education systems. The project was funded by the European Union and is considered the most successful one amongst many others. These projects were developed due to the emergency need for proper education (Soylu et al., 2020). Few components affect the quality of the education for Syrian children at schools. The first one is learning the Turkish language. There are curriculum tracks that help students join Turkish preparatory classes and usual ones with their Turkish peers. According to a survey from almost eighty percent of the Syrian students attending the integration track learned the local language to an advanced degree. Afterward, they could comprehend the usual curriculum as their peers did. Teachers, who were otherwise not prepared to deal with migrant students, found it difficult to teach students who did not speak the Turkish language. Integration projects have raised the capacity of schools by recruiting new teachers and training these teachers with specific teaching methods for the students.

Between the years 2016 and 2020, there was a sharp increase in student fluency in the Turkish language, that too from 20% to 80%. However, certain students who have been attending school for more than three years and yet cannot speak the Turkish language posed an important problem. Fortunately, the projects introduced by the Turkish government have ensured positive outcomes, with more than a million Syrian students now attending schools (Shaherswasli et al., 2021).

Another aspect of education is the experience that students had at school with their peers. Several studies have reported that more than half of the Syrian students face some degree of discrimination or bullying from their peers.

Some reported that they could not interact with Turkish students and, as they had to isolate themselves in the end. Syrian students are less likely to strike a friendship with their peers. This may cause long-term emotional and behavioral drawbacks for them. By virtue of school counselors, teachers, and the inclusion of parents can create an optimal and friendly environment for intervention to take place. Note that, less than 50% of the students did not report any discriminative comments or behaviors from Turkish companies. It is promising for everyone while there are unmoving residual problems for both parties. It is mandated by the constitution and the right of the students in Turkey to attend K12 education entirely free of charge. However, certain parental contributions may be needed, which can pose an economic burden on underprivileged parents. At the beginning of integration progress, there were modest incentives for parents, but many families could not compensate their children's school expenses.

Child labor amongst Syrian families is still a significant problem. Such experiences can lead to the emotional, physical, and economic abuse of children who cannot attend schools. Most families cannot even afford the basic needs of the house such as rent, food, and electricity and the children are therefore exploited as a cheap labor force by employers (Sahin et al., 2020). In such cases, children are often presented with the choice of survival or education, leading to child labor.

Interruption of education is unacceptable for children; therefore, economic aid has to be delivered to those in need until they become independent. Other significant factors prevent children from attending schools such as child marriage and domestic violence. Child marriage and domestic violence affect not only schooling but also cause parental traumas among children. Child marriages are prevalent between low-income families as an economic survival mechanism. Compared to Turkish peers, migrant children under 18 are more likely to marry. Considering marriage under the age of 18 is illegal, there are not many credible statistics for the problem. According to the Hacettepe Institute of Population Studies (2019), the child marriage ratio is between 38% in Syrian children and 21% in Turkish children. When it comes to the need to survive, marrying for economic reasons is the priority before education for migrants. Domestic violence is also another factor that causes trauma in school-age children. A study from Jordan points out that child marriage is linked to poor social conditions, mental health problems and maternal disabilities (El Arab and Sagbakken, 2019). Therefore preventative measures are required to be set by authorities. At schools, teachers and school counselors must be aware of such cases. They need to take care of the student by conducting surveys and then performing a proper counseling service. Both preventative and intervention services should be delivered to the vulnerable population.

Educational assessment of Syrian students

Another common problem according to the survey INSAMER is that students who have difficulties complying with the instruction of teachers are considered requiring special education. Syrian children with disabilities residing in Lebanon faced severe barriers in term schooling (HRW, 2015). Furthermore, in Turkey, those students who are unable to attend classes and have lower grades in exams are required to be evaluated again before continuing in a regular school. The need for psychosocial support because of past traumas or simply lack of language skills is falsely regarded as a low intelligence indicator or special educational needs. Syrian students are more likely to be falsely referred to medical and educational evaluation than their peers according to the same study conducted by INSAMER. Lifting language skills and proper orientation before school has key importance for students to gather the same speed as their peers. Referrals to the Guidance Research Center for diagnostic educational evaluation should be made thoughtfully to prevent false referrals and their consequences, such as social stigmatization. Post-traumatic stress indicators have been observed in almost two-thirds of Syrian children who fled the war (Ceri et al., 2016). Therefore teachers should assess students' past and be aware of their actual needs and their academic performance. In addition, the same study showed that there could be religious and cultural facts specific to the child that affects their attendance and performance (Ceri et al., 2016; Sirin and Rogers-Sirin, 2015). On the other hand, the study also showed that Syrian students are two times more likely to be introverted than Turkish peers. This fact correlates positively with the effects of depressive symptoms mentioned in the research that volunteer psychiatrists conducted (Ceri et al., 2016; Shaherswasli et al., 2021).

According to the UN data from 2015, almost half the children who fled and resettled are out of school, therefore, the intergenerational loss is inevitable. Almost nine out of every ten girls are out of proper school in Lebanon. The ratio is way lower but still relevant in the case of Syrian girls in Turkey (UNHCR, 2021). Since September 2014, according to the Turkish National Ministry of Education, Circular 2014/21, Syrians under temporary protection regime are accepted to Turkish public schools. Grade placement is an issue for those who were cut out of school when the war began. According to the qualitative research from Human Rights Watch (HRW, 2016), students placed in lower grades suffered from language barriers and learned almost nothing. Afterward, there was a gradual increase in the number of students attending school. This may cause poverty and child marriages in the short term but also leaves many children economically exploited.

Social integration at school

A positive school environment for students plays a crucial role in gaining cognitive, emotional, and social abilities. Their attitude has to be favorable to the school wherein they can flourish and have a successful future life. The authors have projects for integrating into the system, but they also need projects to increase interaction between students. Teachers need to undergo culturally sensitive education and be trained to deal with specific populations. Otherwise, the outcomes of the education for Syrian children may be underwhelming. Academic success and social skills cannot be developed if children were to create friendships by ethnicity and language. Language is one of the predictors of harmonization, as discussed before. Projects that addressed this issue were prevalent and showed success in the past, and more students have international students as friends now. Teaching values like equality and respect is essential since students have a tendency of hating each other because of certain prejudices.

Surveys showed that only a third of the Syrian students reported a casual friendship with their Turkish peers. This matches with the similar answers from the parents. Half of the teachers reported that social harmonization between students is adequate, and the rest reported it as being inadequate. Teachers who joined the interviews believe that Syrian students show better perseverance and self-confidence than Turkish peers to succeed in the classroom. The schools in fields where migrants live densely also showed a lower degree of acceptance for international students (INSAMER, 2021).

The educational administration has critical role when implementing inclusive policies. Hence, educational leadership is essential to develop better communication between students and parents. Otherwise, vulnerable populations may not easily integrate into the new education system. Thus, there is an urgent need for social support for these communities. In-service training of teachers and principals and a counselor at school plays a crucial role in developing better communication and understanding.

Psychological well-being of Syrian children

In the last few decades, approaches to psychological well-being have attempted to measure fundamental human needs and functioning. Humanistic approaches to mental health have led to the development of scales to evaluate the positive functioning of people (Diener et al., 2009). It is defined as the difference between positive and negative effect as it ordinarily used in dictionary meaning (Ryff and Keyes, 1995). Under harsh conditions like war and natural disasters, the whole society may live traumatic events. These experiences may overtake biological and psychological coping mechanisms. Trauma is typically defined as the abrupt disruption of bonds that bring together humans. As a result, cognitive and emotional disorders can be seen, and subsequently, psychopathologies may emerge. Trauma in childhood is notably more severe than in adulthood because horrifying experiences have the most hazardous effects when cognitive functions and biological systems are not mature yet (Van der Kolk, 2003).

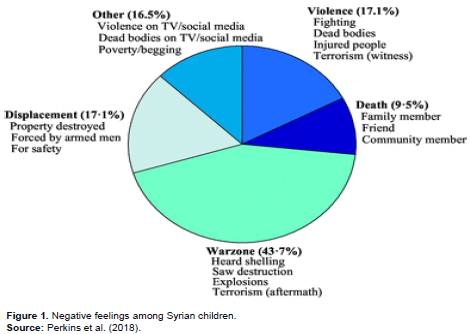

There are three types of psychological risk factors among Syrian children: personal, social, and environmental problems. The type of events that they are exposed to in their home country affects their psychological well-being in the long run. Psychopathologies emerge according to the intensity and degree of exposure. Direct exposure to violence and death are the biggest threats to mental health. The number of traumatic events and length of exposure to it, witnessing other traumatic events such as torture or captivity and killing a family member, affects psychological problems (Gormez et al., 2018). Figure 1 shows the distribution of negative feelings among Syrian children.

Syrian children experienced traumatic events and war- related stress, which is a critical factor affecting psychological well-being. Above figure indicated the variety of traumatic events that Syrian students are possibly experienced. One in tenth of Syrian children faced death of at least one person they know. Children who are witnessed violance such as fighting, dead bodies or terrrorism double the number of those who lost an acquintance. In particular, roughly half the children are exposed to warzone. There is an urgent need for mental health care services amongst those children. Schooling has a pivotal role in reaching out to children who are of school age. Proper guidance to students and their families and referring them to proper medical experts is essential to prevent the long-term effects of consistent trauma. Early childhood experiences have an essential role in both long-term development and also on society as a whole. Children subject to the war are at a higher risk of developing mental health problems. Mental health issues are present in a considerable margin of society and need to be addressed comprehensively (Sirin and Rogers-Sirin, 2015; Perkins et al., 2018). This paper primarily evaluated the importance of preventative measures such as schooling and particularly, the integration and guidance of children and families.

Accommodating a new culture can be a stressful task for children who are forcibly displaced from their homes.

Acculturative distress emerges as a consequence of adjusting to a new environment resulting in psychological distress, low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. However, studies show that sharing similar values such as religion, culture, and being a part of a family can reduce acculturative stress (Gormez et al., 2018; Ceri et al., 2016). Even though there is a five-year gap between the two studies mentioned here, the residual effects of war still exist among Syrian children. The children who fled the warzone might experience trauma and loss, among other long-term effects on their development. In addition, they might have experienced armed conflicts and gunfires, leading to devastating impacts on children's mental health. Studies show that nearly half of these children experience post-traumatic stress disorder or somatic disorders (Ceri et al., 2016; Sirin and Rogers-Sirin, 2015). Syrian students that has faced trauma may not succesfully accommodate as their Turkish peers. Thus the main focus should be on the psychological well-being of those children more than their harmony in the classroom. Subsequently, they need to be in an orientation program in adcance to their studies. Teachers should be aware of the children’s bacground and hidden effects of trauma on learning which requires in depth consideration at schools.

A study conducted by Gormez et al. (2018) unexpectedly discovered that there is no difference in the psychopathologies experienced by those who can speak Turkish and those who cannot. The reason for this finding has prompted further questions. Researchers commented provisionally on the cohabitation of Syrians in a large neighborhood with a comparatively sizeable Arabic-speaking community. Therefore they did not depend on the language for social support. Furthermore, studies have also revealed that psychological distress has a relation with time. Lack of social support may increase psychopathologies in the long term. The absence of social support in the early days of displacement can cause devastating outcomes (Gormez et al., 2018). Study shows that loss of a family member is a significant predictor of developing PTSD and suggest that there might be periodic screenings for Syrian Children at the child care hospitals (Yayan et al., 2019). Studies outline that many risk factors affect the psychological well-being of Syrian children. To adapt successfully to a new society, they need to reach psychosocial support and schooling, a significant harmonizer for students.

DISCUSSION

Traumatized children, no matter how safe their shelter can be, the suffering from the war continues. Memories persist, and unconsciously or consciously, they re-experience the events in their dreams. Somatic complaints persevere, and enuresis is prevalent. Researchers conducted a counseling group that consisted of displaced children and asked if they can draw a draw a place where they feel safe and protected. They could not draw anything but war memories. Most of the pictures contained graphic content and included dead people, shellings, and tanks (Hamdan-Mansour et al., 2017).

This signals the urgency of the situation. Some of these people have spent almost ten years experiencing the conflict. Large numbers of children do not participate in a mental health examination. As children become high school students, their needs are reshaped according to the current situation.

The needs of the children cannot be limited to basic physical needs. The study suggests that a comprehensive multidimensional approach and guidance to mental health services are needed for children. The immediate necessity for emotional and social support is evident. Services provided to the children should include counseling which is adjusted to their development. Their access to the proper counseling services should be increased as soon as possible after finding a new place in the host community. Officials and humanitarian agencies have to team up together and create solutions to address these problems comprehensively (Hamdan-Mansour et al., 2017). A particular study revealed that Syrian and Turkish doctors benefited from the mental health gap action program (mhGAP), whereby general practitioners and psychiatrists practicing in the field were given training. Beneficiaries of their service gave positive feedback, and they became more likely to seek psychological aid (Karao?lan et al., 2020).

CONCLUSION

Throughout the years, Syrian children living in Turkey have been exposed to various educational and mental health problems. There is a need to carefully investigate the sociocultural, psychosocial, and educational aspects of the issue.

Despite the substantial effort to address needs of Syrians under temporary protection, there have not been satisfactory results yet. Counseling and psychosocial support should be openly offered even if beneficiaries do not seek such services as a primary issue. These services should be assessed within the basic physical needs of children. Not only children but also their families need these services. Existing literature showed that Syrians even in different countries has commonly experienced trauma but sought and found limited psychosocial aid. In particular they must be encouraged to seek for help to get education and health care. Counselors, teachers, and doctors working with Syrian children are required to pay adequate attention to the sensitive issues that may persist. Trained practitioners must be assigned to empower children's psychological well-being. Further, to help them navigate their trauma and long-term psychopathologies like depression and anxiety.

Government institutions and international humanitarian organizations make an effort to help those still suffering from war. They need to collaborate effectively to create a solution-based intervention for emergencies and long-term positive outcomes. Other vulnerable populations are not mentioned in this paper, however, they all require counseling and mental health services. Every neighboring country of Syria has an official language of Arabic except for Turkey. Given, Turkey hosts the largest number of Syrians, the language constraints are quite important. Language is essential for education and to access basic mental health facilities. The language barrier might also be a significant obstacle in adapting to a new place and receiving proper services. It is recommended that the local language be learned to ease the everyday life in the host communities (Yalim and Kim, 2018).

Throughout the article, a relation between war and trauma established on the track of the different studies that took place in the field. Syria crisis has overwhelm the region within the region and hundreds of study conducted about its effects on people. Most of the research conducted on local places and did not adopt a hollistic approach to the issue.

This study agglomerated the various data from different countries that Syrian students had to flee. Thus, delivering an integrative approach to the problem by conducting a systematic literatur rewiev is going to help further studies to concentrate on the small prints that have a huge effects but gained less awareness.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

Atac E (2019). Modeling educational inequalities: Class, academic achievement, and regional differences in Turkey. Education and Urban Society 51(5):659-692. |

Aydin H, Kaya Y (2017). The educational needs of and barriers faced by Syrian refugee students in Turkey: A qualitative case study. Intercultural Education 28(5):456-473. |

Çelik Y (2018). Türkiye'de Suriyeli çocuklara yönelik uygulanan egitim politikalarinin incelenmesi: tespitler, sorunlar ve öneriler. Master Thesis. |

Ceri V, Özlü-Erkilic Z, Özer Ü, Yalcin M, Popow C, Akkaya-Kalayci T (2016). Psychiatric symptoms and disorders among Yazidi children and adolescents immediately after forced migration following ISIS attacks. Psychiatrische Symptome und Störungen bei jesidischen Kindern und Jugendlichen unmittelbar nach erzwungener Migration infolge von IS-Angriffen. Neuropsychiatrie: Klinik, Diagnostik, Therapie und Rehabilitation: Organ der Gesellschaft Osterreichischer Nervenarzte und Psychiater 30(3):145-150. |

Diener E, Wirtz D, Biswas-Diener R, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S (2009). New measures of well-being. assessing well-being: the collected works of Ed Diener. Social Indicators Research Series 39:247-266. |

Dillioglu B (2015). Suriyeli mültecilerin entegrasyonu: Türkiye'nin e?itim ve istihdam politikalari. Akademik Orta Dogu 10(1). |

Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) (2021). Temporary Protection Statistics. |

El Arab R, Sagbakken M (2019). Child marriage of female Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon: a literature review. Global Health Action 12(1):1585709. |

European Commission (2016). European Migration Network Glossary. |

Gay G (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press. |

Gormez V, Kiliç HN, Orengul AC, Demir MN, Demirlikan S, Demirbas S, Babacan B, Kinik K, Semerci B (2018). Psychopathology and associated risk factors among forcibly displaced Syrian children and adolescents. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 20(3):529-535. |

Hamdan-Mansour AM, Abdel Razeq NM, AbdulHaq B, Arabiat D, Khalil AA (2017). Displaced Syrian children's reported physical and mental well-being. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 22(4):186-193. |

Hacettepe Institute of Population Studies (HIPS) (2019). 2018 demographic and health survey-Syrian migrant sample (NEE-HÜ.19.03). |

Human Rights Watch (HRW) ( 2015). "When I Picture My Future, I See Nothing": Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Turkey. Human Rights Watch. |

Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2016). Growing Up Without an Education": Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Lebanon. Human Rights Watch. |

Karaoglan AK, Alatas E, Ertugrul F, Malaj A (2020). Responding to mental health needs of Syrian refugees in Turkey: mhGAP training impact assessment. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 14(1):1-9. |

Knopf JW (2006). Doing a Literature Review. PS: Political Science and Politics 39(1):127-132. |

Perkins JD, Ajeeb M, Fadel L, Saleh G (2018). Mental health in Syrian children with a focus on post-traumatic stress: a cross-sectional study from Syrian schools. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiology 53(11):1231-1239. |

Ryff CD, Keyes CLM (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69(4):719-727. |

Sahin E, Dagli TE, Acarturk C, Dagli FS (2020). Vulnerabilities of Syrian refugee children in Turkey and actions taken for prevention and management in terms of health and well-being. Child Abuse and Neglect 119:104628. |

Seydi AR (2014). Türkiye'nin Suriyeli siginmacilarin egitim sorununun çözümüne yönelik izledi?i politikalar. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 31. |

Shaherswasli K, Erel S, Özdenler M, Cengiz B (2021). Suriyeli Ö?rencilerin Türk E?itim Sistemine Entegrasyonu. INSAMER. |

Sirin SR, Rogers-Sirin L (2015). The educational and mental health needs of Syrian refugee children (P 13). Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. |

Soylu A, Kaysil? A, Sever M (2020). Refugee children and adaptation to school: An analysis through cultural responsivities of the teachers. Egitim ve Bilim 45(201). |

United Nations (1948). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. |

UNHCR (2021). Turkey: Education Sector Monthly Dashboard, UNHCR Operational Data Portal |

United Nations Research Institute For Social Development (UNRISD) (1994). Social Integration: Approaches and Issues. World Summit for Social Development, UNRISD Briefing Paper No. 1 |

Van der Kolk BA (2003). Psychological trauma. American Psychiatric Pub. |

Visentin S, Pelletti G, Bajanowski T (2017). Methodology for the identification of vulnerable asylum seekers. International Journal of Legal Medicine 131(6):1719-1730. |

Weichselbaumer D (2016) Discrimination Against Female Migrants Wearing Headscarves. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10217. |

Yalim AC, Kim I (2018). Mental health and psychosocial needs of Syrian refugees: A literature review and future directions. Advances in Social Work 18(3):833-852. |

Yavuz Ö, Mizrak S (2016). Education of School-age Children in Emergencies: The Case of Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Göç Dergisi 3(2):175-199. |

Yayan EH, Düken ME, Özdemir AA, Çelebioglu A (2019). Mental health problems of Syrian refugee children: Post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 51:e27-32. |