Cultural diversity and business schools’ curricula: a case from Egypt

Опубликована Июнь 1, 2016

Последнее обновление статьи Дек. 9, 2022

Abstract

The French Ecole Supérieure Libre des Sciences Commercial Appliquées (ESLSCA) in Paris is one of the most important global culturally diverse private business schools in terms of its number of branches and its history. ESLSCA has had a branch in Cairo in Egypt for about 17 years. This qualitative study seeks to focus on ESLSCA-Egypt branch to investigate the extent to which cultural diversity is included in its MBA curricula. The main methods for collecting data are document analysis, a number of semi-structured interviews, and a review of relevant literature. The study findings have meaningful implications for the practices of business schools’ education and training

Ключевые слова

Education, curricula, business schools, cultural diversity, Egypt

Introduction

Although research on cultural diversity has started in the 1970s by investigating the inequalities derived from racio-ethnic lines and gender, the definition of cultural diversity has expanded to represent “the differences in ethnicity, background, historical origins, religion, socio-economic status, personality, disposition, nature and many more” (Vuuren, Westhuizen and Walt, 2012).

Business schools have started to link their various levels of knowledge with the various social, political, emotional, psychic, legitimate, and symbolic concerns in their surrounding environment. They consider that being academically as well as socially integrated is a necessary paradigm to follow in the era of globalization and diversity (Misra and McMahon, 2006).

Consequently, many business schools have started to provide training and education for their students in the area of cultural diversity. They provide cultural diversity as a discrete course or as a standalone training/coaching program (Kormanik and Rajan, 2010; and Morrison, Lumby & Sood, 2006). Many of them provide it as a main part of human resource management/marketing or general management courses.

Due to the fact that one of the researchers is Egyptian, and his country witnessed two political revolutions in the last five years and, currently, a state of division and conflict as street fights, strikes and protests have become the main daily phenomenon in Egyptian life, this research focuses on Egypt. The researchers have considered that the lack of acceptance of others who Ruth Alas, Ph.D., Professor, Head of Management Department, Estonian Business School, Estonia.

Mohamed Mousa, Ph.D. Student, Estonian Business School, Estonia. are different in religion, gender, age, social class, income, educational background, and political affiliation might be the main dilemma facing the citizens of this country nowadays.

Accordingly, the two researchers have chosen to do their research in a French private post-graduate business school which started its business in Egypt 17 years ago. This school, the Ecole Superieure Libre des Sciences Commercial Appliquees (ESLSCA), provides both English and Arabic educational business programs.

The researcher examined the educational philosophy of ESLSCA-Egypt by seeking answers to the following research questions:

- To what extent is cultural diversity included in ESLSCA business school’s curricula (content and processes)?

- To what extent do the MBA students of ESLSCA business school experience, learn and find cultural diversity in their curricula and how?

- Literature review

1.1. Cultural diversity. Culture means “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005, p. 28). The concept diversity refers to “the state of being different or varied”. According to Vuuren, Westhuizen and Walt (2012, p. 156), cultural diversity is “the differences in ethnicity, background, historical origins, religion, socio-economic status, personality, disposition, nature and many more”. Moreover, Heuberger, Gerber and Anderson (2010, p. 107) defined it as “many types of differences, such as racial, ethnic, religious, gender, sexual orientation, and physical ability, among others”. The concept of cultural diversity has been referred to as “a source of sustained competitive advantage derived from a large pool of resources, ideas, opinions, values, resulting in a broader range of task-related knowledge, abilities and skills than homogeneous ones” (Zanoni et al., 2009, p. 11).

Ogbonna and Harris (2006) indicate that through a positive appraisal of cultural diversity, firms may decide to recruit diverse international workforces in order to have better access to and understanding of different markets. It is a case of enhancing business range by consciously selecting a broad variety of diverse personal qualifies in order to attain competitive success. Accordingly, Roberson and Park (2007) consider that a multicultural workforce results in productivity and competitive benefit. Moreover, working in/with a multicultural workforce helps in attracting and retaining talents. This helps in reducing absenteeism and turnover. Moreover, Humphrey et al. (2006) stress that educating people to appreciate cultural diversity entails a support for the values of inclusion and solidarity. Countries can’t mirror any democratic norms without promoting respect for diversity and its corresponding values of freedom, equality and tolerance.

1.2. Cultural diversity and business schools. Given the increasing trend of multinational firms to hire people from culturally diverse backgrounds and people who understand how to deal with different cultures as well, business schools are “called upon to demonstrate “commitment and actions in support of diversity in the educational experience” (AACSB, 2004, p. 10). In order to prepare their students for an era full of diversity, business schools need to integrate academic components in fight of social trends (Kormanik and Rajan, 2010; and Fenwick, Costa & D’netto, 2011). Moreover, attraction and retention of culturally diverse students and staff can lead to a greater awareness of diversity and more openness to the globalized world.

Educating in a culturally diverse environment: With the changing demographies around the world, cultural diversity within many communities is increasing. Business schools have the responsibility of providing their students with knowledge necessary for developing a kind of understanding of cultural diversity (AACSB, 2004). In order to instigate culturally diverse communities, any educational component is required to encourage students to not only respect differences among various groups but also demonstrate this respect towards all ethnicities, languages, religions and other cultural components that may exist in their society (Dogra, 2001; Hartel, 2004). That’s why the studies of Gay (2013) and Grobler et al. (2006) affirm the need to connect inschool learning to out-of-school living through accepting others’ recognizable values and beliefs.

Teaching cultural diversity: Universities have the responsibility of preparing their students for a diverse world. The fact behind this responsibility is that the more students become aware of diversity between people and cultures, the more effective they become in their jobs, lives, and future (Heuberger, Gerber and Anderson, 2010; Roberson & Park, 2007). Therefore, designing a cultural diversity course is a main requirement for developing personal and professional skills to be utilized in multicultural societies (Davis, 2005; Julius, 2000). In order to develop a course about cultural diversity, at least three main objectives need to be considered (Gay, 2013):

- The first is to understand social and individual characteristics (e.g., food, habits, time consciousness etc.) of a culture.

- The second is to understand the differences and similarities between one culture and another. What is essential for one culture may not be so vital to another.

- The third is to develop cross-cultural skills, especially in communication and negotiation. A course about cultural diversity illustrates that acknowledging another culture does not mean completely agreeing with it but, at least, understanding how to deal with it.

The content of this course should include material developed by instructors from various disciplines besides one or more textbooks (Heuberger et al., 2010). Accordingly, students are expected to gradually progress from perceiving simple concepts to more complex ideas (Hargreaves, 2001).

1.3. Egypt, when spring yields black flowers. The Arab Republic of Egypt, also known as “Misr” or “Egypt”, is the country that has the largest population in the Middle East and the Arab region. In April 2009, the development indicators database of the World Bank estimated the population in Egypt by about 83.1 million people (World Bank, 2009). Egypt is situated in the eastern part of North Africa. It occupies a strategic location owing to the Suez Canal, a vital waterway for the world’s commodities, especially oil. This country stretches from the border with Libya in the west to the Gaza strip in the east. Due to its history, location, population, culture, and military power, Egypt is perceived by the world as a leader in the Arab region. The following part shows more details about all facets of life inside Egypt throughout its last 33 years.

1.3.1. Egypt during Mubarak’s Era (1981-2011). Since 1981 fill January 2011, Egypt had Hosni Mubarak as a president. During all of his period of presidency, Mubarak was the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and the commander-in-chief of the police. He had the right to appoint the prime minister, security leaders, religious figures, and other high rank executives. Clearly, authoritarianism was the main feature of Mubarak’s era (Bauer, 2011) simply because he had the right to veto legislature. Furthermore, the parliament had little influence over the government.

Despite several trials to boost Egypt’s economic performance, a study made by the International Institute for Conflict Prevention and resolution in 2009 highlights that nearly 17% of Egypt’s population lives below the poverty line. Increasing unemployment further adds to this dilemma. Zoubir (2000) elaborates that the bad Egyptian economic situation during Mubarak’s era worked as a breeding ground for social and cultural tensions and subsequently, for religious extremism.

1.3.2. Egypt after January 2011. The first few weeks of 2011 witnessed a fundamental change in leadership and government in Egypt. Millions of Egyptian people went out for three weeks in the streets calling for their political freedom, social justice, and other rights. This historical break has remained open-ended and stimulates many questions, suggestions and expectations for the Egyptian rapid changing scene. What is disturbing in this status quo is that street conflicts, torture, and the rising and diminishing of Islamic conservative parties have tended to become phenomenal of the daily life of the country.

Given what is highlighted before, one of the main aims of business schools is to prepare their graduates to participate in the development of their society. This can be attained through addressing and solving existing problems as well as becoming ready to face any expected and/or unexpected problem, phenomena or crisis (Alzaroo and Hunt, 2003). Needless to say that designing up-to-date curricula and learning environment is an undisputed requirement for any system of higher education (Mahrous and Kortam, 2012). Although Egyptian society is experiencing new waves of political, social and economic challenges, the study of Soliman and Abd Elmegied (2010) has summarized that the main struggles facing the society are, to a great part, neglected in Egyptian higher education and schools. The matter that elaborates, to some part, the absence of many social, cultural, and economic problems (e.g., unemployment, illiteracy, the rising cost of living, and crimes) from the various curricula of Egyptian and foreign universities work in Egypt.

2. Research design

2.1. Procedures. This is a qualitative study conducted in ESLSCA-Egypt, a business school that offers post-graduate programs in Egypt. The school was carefully selected because it is a school that works in Egypt and provides its program in both English and Arabic and targets both Egyptian and non-Egyptian students. This indicates a clear case of cultural diversity. On the 4th of April, 2015, one of the researchers met with the marketing manager of ESLSCA-Egypt to agree on the methods of the interviews with the students.

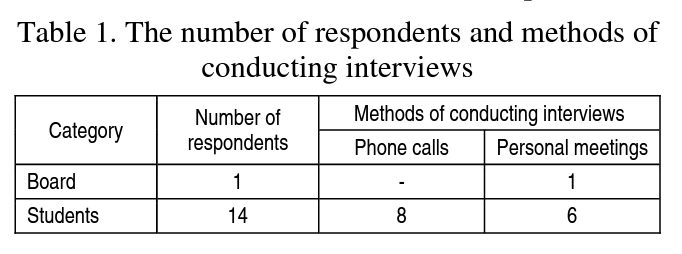

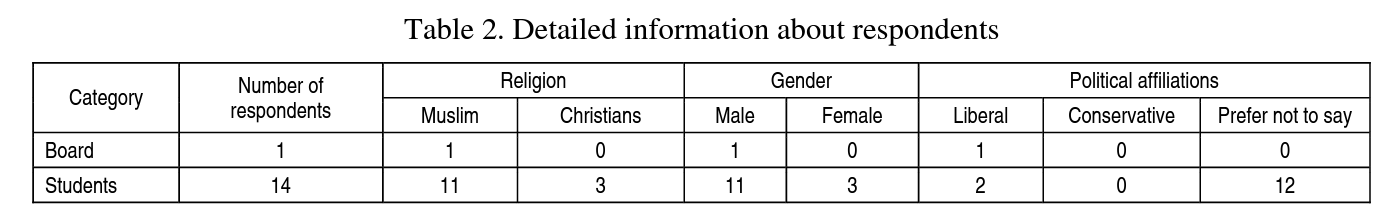

2.2. Participants. ESLSCA granted the researchers permission to conduct interviews with one member of the board, and four MBA students. However, out of personal initiative, the researchers were able to contact an additional number of current MBA students. Thus, the total number of interviews accounted for fifteen which included both phone calls and direct interviews.

2.3. Observations. It was observed that during the interviews the participants were reluctant to uncover critical details with regards to the school out of fear of giving a negative impression that may compromize their standing with the university and, in turn, their assessment and results. Some even went to the extent of refusing to have their interviews recorded when they were informed that the researcher would record them. Moreover, because of the novelty of the procedure for some and because of their overloaded schedules, many participants asked that the interview questions be answered via phone instead of face to face. Added to this, the marketing manager instructed the researcher to conduct all interviews in Arabic.

2.4. Interviews and documents. The interviews aimed at investigating the key terms of the research, which mainly focuses on two questions. To answer the first question, the researchers investigated if there were any policies or initiatives regarding equipping its staff and students with values of solidarity, tolerance, inclusion, and cultural sensitivity. Unfortunately, none of these values were found in any written form because the school lacks any written document outlining its practices and activities. Furthermore, the researcher found difficulty accessing the course descriptions, field notes, and professor handouts, and it was only through students’ personal notes that the researchers were able to get a glimpse of the content and materials actually referred to in order to prepare for the exams. As for the second question, the researchers discovered during the interviews that the participants were, to a great part, unaware of the concept of cultural diversity and its repercussions on the Egyptian scene as most showed no interest in the impact of the current sociopolitical events on their studies.

2.5. Analysis. After conducting the interviews, detailed transcripts were made in which the contents of the interviews were typed out. Needless to say that the most interesting findings and information derived from the transcripts were coded. Owing to the specific focus of this research, questions and answers of the research were related to one of these concepts, namely, cultural diversity, teaching cultural diversity and accepting others.

2.6. Research quality indicators. Within the research, three criteria of trustworthiness were used to investigate the quality of the research: reliability, internal validity, and external validity. Reliability was enhanced through audio recording for some of the conducted interviews. Moreover, the researchers tried as much as they could to carefully select his participants. Internal validity was enhanced by cyclical proceedings of data collection and analysis. Owing to ESLSCA’s desire, the interviews were conducted in Arabic. However, this didn’t affect the accuracy of the information provided because one of the researchers has Arabic as native language. To establish external validity, the researchers examined peripheral documents such as students’ handouts and textbooks.

3. Results

The ESLSCA’s marketing manager sampled for the researchers four students who are of different religions (Muslim and Christian), political affiliations (liberal and conservative), and ages. ESLSCA’s marketing manager thought that selecting respondents from different ages, religions, educational backgrounds, and political affiliations serves, to some degree, to establish external validity of the results. As mentioned earlier, the researchers depended on their personal relations and networks to find more students for his research. Table 1 elaborates a number of facts about the respondents.

3.1. Document analysis. The researchers started out their endeavor by analyzing ESLSCA’s policies and MBA’s content and, subsequently, conducting interviews with ESLSCA’s suggested participants. Unfortunately, the researcher couldn’t find any written policy in ESLSCA-Egypt with regards to cultural diversity, or even its MBA’s content. Upon inquiring about the MBA prospectus, the researchers were merely given a small (2 pages) brochure about ESLSCA’s MBA program outlining objectives and courses from ESLSCA’s marketing manager. Moreover, the researcher found the same content of the small brochure available on ESLSCA’S website (www.eslsca.org). This brochure only offers the names of the courses included without any description of the content of each course, the weight of each course credit, or any other relevant data. Accordingly, the researchers investigated the textbooks, course descriptions, and courses materials of ESLSCA’s MBA through discussions with students, on the one hand, and examination of student handouts, on the other.

The researchers found that the obligatory courses at ESLSCA’s MBA are twelve. Of these, there are four courses in management (contemporary management, leadership, entrepreneurship, and strategic management), two courses in research (quantitative methods and research methods for managers) besides a course in economics (managerial economics), a course in marketing (marketing management), a course called international business law, and, finally, a course called cross-cultural communication and negotiation. The latter course was carefully investigated to check if its content is related to the issues of cultural diversity, identity, equal opportunity, affirmative action, and preferential selection; however, this was not the case. The researchers also investigated if ESLSCA-Egypt organizes any initiatives (training course, workshop, conferences, etc.) related to cultural diversity issues and/or the Egyptian current political and social shifts, but, unfortunately, they couldn’t find any evident effort in this regard; the result that was confirmed through the interviews as well.

3.2. Interviews analysis. Given the fact that a number of respondents were chosen through ESLSCA’s marketing manager upon the delegation he received from ESLSCA’s board, they were not so much eager to talk and express their opinions; however, the researcher did his best to extract as much information as he could through reiterating the same questions to the same respondent in various ways and repeating the same questions to multiple participants. The following are the main points extracted from the researchers’ questions and the respondents’ replies after transcribing the interviews conducted:

When asked about the meaning of cultural diversity, the majority of interviewees referred only to gender and religious equality. Only respondent five mentioned that “cultural diversity includes the differences in gender, religion, educational background, political affiliation, and so on”. The researchers found that the respondent was not only a graduate of a Faculty of Arts but had also participated, as a representative for the company he works in, in a workshop about marketing across diverse cultures in Italy before.

The third question concerns the link between ESLSCA’s MBA courses and the changes in the Egyptian society. In this regard, the majority of interviewed students considered that there is no link between their courses and the changes in the Egyptian society, and there shouldn’t be any link because as they claim they are business students. Respondent seven said: “I am here to gain knowledge about marketing not the tolerance between Muslims and Christians. It is the job of sociology majors”. Moreover, many of them confirmed that the professors asked them not to talk about politics during their lectures. Accordingly, when asked about any cases of discrimination because of political affiliations or religion faced by any of ESLSCA’s students, all of the interviewed students clearly said that they didn’t face any kind of discrimination or any problem resulting from differences in religion, gender, and/or political affiliation.

Five of the interviewed students mentioned that the majority of their lectures were delivered in a mix of Arabic and English. Some of them preferred it this way because the official and usable language for them is Arabic; however, many others indicated their need to be taught in English. This is to enhance their linguistic capabilities from the one side and to compensate the fact that ESLSCA-Egypt doesn’t offer them any language training/course from the other. Three of the students expressed their desire to find professors from other nationalities/backgrounds because all of their professors are from Egypt, and even ESLSCA’s administration staff is completely Egyptian.

One of the researchers’ important questions was whether any of ESLSCA’s-Egypt business school course content offers some knowledge about accepting others or not. Most of the students there elaborated that despite the main focus being on commerce and business management, they may have heard something before about accepting others, tolerance, and solidarity; however, this wasn’t a main part of their courses and was merely mentioned incidentally in one or two lectures.

The Paris trip was a matter of debate between the researcher and many of the interviewed students. The website of ESLSCA reveals that ESLSCA organizes a trip for a month to Paris every year. The students confirmed that this trip is only for five days and many of them had asked ESLSCA’S board to make it 14 days, but ESLSCA refused to do so.

Asking about whether ESLSCA’s MBA curricula meet the student’s expectations or not yields many conflicting views. Some of the students who seek just the certificate consider that ESLSCA’s MBA meets their expectations, and they don’t want any other courses or training in cultural diversity or any other topic. Other students consider that ESLSCA’s MBA needs many improvements. Both respondent four and thirteen consider recruiting European professors will add more value to the program. In a phone call with the respondent four, he stated “I can’t see the difference between ESLSCA’s MBA which is French and an MBA from any Egyptian governmental university; same methods of teaching, to a large degree, same courses, and even the same way of assessment. Even the English proficiency level of both professors and students needs to be reviewed”.

4. Findings

Although the present thesis was aimed to determine the extent to which cultural diversity is included in ESLSCA’s business school, Egypt and the extent to which cultural diversity is taught, experienced, and adopted in its curricula, the researchers unintentionally found themselves responsible for evaluating the whole educational process practiced by the school. Consequently, the following are the answers to the questions of the research.

- To what extent is cultural diversity included in ESLSCA business school’s curricula, its content and processes?

After careful review of the courses included in ESLSCA’s MBA, the researchers found that the obligatory courses for all students in the program are twelve. These are classified into two courses in accounting (accounting for managers and financial management), four courses in management (contemporary management, leadership, entrepreneurship, and strategic management), two courses in research (quantitative methods and research methods for managers) besides a course in economics, a course in marketing, course in international business law, and, finally, a course in cross-cultural communication and negotiation. The researchers expected at first that the latter course would cover issues pertaining to cultural diversity, diverse identities, affirmative action, and preferential selection; however, this was not the case as will be discussed later.

The researchers also investigated the textbooks, course descriptions, and course material of all ESLSCA’s MBA courses, but found that all these courses do not show any significant concern for cultural diversity, cultural differences, and cultural sensitivities.

Gay (2013) indicates that teaching in a cultural diverse environment (Egypt is currently witnessing a status of diversity) requires a culturally responsive approach to connect in-school learning to out-of-school living - the matter that forces course content to be expanded and, subsequently, to include expressions, beliefs, and recognizable values in surrounding societies. Unfortunately, that is not the case in ESLSCA business school, Egypt. The contents of all courses focus only on business, commercial transactions, and managerial decision making without paying attention to the political, cultural and social shifts in the Egyptian environment. The aspects of women empowerment, youth empowerment, social justice, and the big discrepancy in wages among different classes in the Egyptian society, which constitute a hot daily discourse in media and even among layman, are to a great extent absent in ESLSCA’s business school, Egypt.

In its cross-cultural communication and negotiation course, discussions with the students demonstrated that the main aim of this course is to develop cross-cultural skills to assist in global interactions and negotiations. This reflects only a part of what is highlighted by both Heuberger et al. (2010) and Gay (2013) when expressing that teaching a course in cultural diversity should first start with understanding both individual and social characteristics such as communication, dress, food, time consciousness, and habits in a given society, comparing the differences and similarities between cultures because what is essential for one culture may not be vital to another, and, finally, developing these cross-cultural skills for communication and negotiation.

Another important point that deserves to be mentioned is the method of assessment of ESLSCA’s students, which consists of written tests of material rote learned mostly from teachers’ handouts. This method of education doesn’t make any effective contribution to the country’s economic, social, and political development because it depends for a great part on memorization rather than any investigation of practical value (Hargreaves, 2001). It also doesn’t grant opportunities to investigate case studies of cultural diversity in its surrounding environment such as factories, companies, universities, and diverse forms of governmental organizations.

Furthermore, although a study made by the AACSB (2004) confirmed that business schools should make business cases for diversity, provide opportunities for intergroup contact, and also adopt cultural relevant concepts through experimental learning, ESLSCA school doesn’t offer any kind of training in cultural diversity, which is a most surprising issue. The school is working in a country witnessing subsequent revolutions and, subsequently, social shifts, movement toward democracy, and, at the same time, a lack of tolerance between some classes of the society. This climate should ideally foster initiatives (training, coaching, workshops, and mentoring) to develop a kind of awareness towards accepting cultural differences (Roberson et al., 2001). However, ESLSCA shows little commitment in support of harmony among different social groups. It, seemingly, considers providing the theoretical content of an MBA and a few postgraduate diplomas in banking and marketing the whole role it should do.

It seems clear that the educational content of all ESLSCA’s MBA courses doesn’t fully touch on the elements of primary social heritage, nor does it express the current political, cultural and social values. ESLSCA, to a great part, doesn’t consider cultural diversity as a part of its strategy. Therefore, it neglects the fact that cultural diversity training is much more required than before to respond to the challenges in both the Egyptian and global world, on the one hand, and to disseminate the soul of accepting the other in the society it works in, on the other.

- To what extent do the MBA students of ESLSCA business school experience, learn and find cultural diversity in their HRD curricula and how?

Despite the fact that the Egyptian society now is increasingly facing a state of division and diversity, the researchers have found difficulty in identifying aspects of cultural diversity in ESLSCA curricula. ESLSCA curricula do not respond to this state, and there are no course components directly addressing it. This is a disturbing fact because many organizations see cultural diversity not just as a one-time seminar experience but as an ongoing training program offered at regular intervals (Misra and McMahon, 2006). Moreover, many international organizations are already integrating aspects of cultural diversity into professional development training such as that for marketing, sales, production, and communication (Roberson et al., 2001). Furthermore, Codling and Meek (2006) illustrate that the inclusion of cultural diversity in higher education requires devoting attention to religious groups, ethnic minorities, and local communities when designing the content and educational components. This may affirm the commitment to diversity in ideas and people (AACSB, 2004).

Much uncertainty is also evident from the interviews on what cultural diversity means to ESLSCA-Egypt. When asking about the possibility of preparing a course about cultural diversity in Egypt, four of the interviewed students mentioned that there is no difference between Muslims and Christians in Egypt, nor men and women in the corporate sphere. They explained that many Egyptian women are currently occupying many leading positions. Their answers reflect that there is no full understanding for the meaning of cultural diversity which goes beyond the aspects of gender and religion to include differences among individuals (tall, short, thin, bald, blonde and so on) and differences among subgroups in all societies (age groups, sexual preferences, socioeconomic status, languages and so on) (Vuuren et al., 2012). This lack of understanding of the meaning of cultural diversity negatively affects the issue of training ESLSCA’s academic staff in the area of cultural diversity.

Furthermore, the researchers didn’t touch upon the ongoing relationship between ESLSCA and the Egyptian business community in forms of consultations, feasibility studies, and other means of collaboration. With this regard, ESLSCA lacks the potential and initiative to handle real cases of cultural diversity inside the Egyptian corporate environment.

Although Grobler et al. (2006) highlights that any discourse about cultural diversity should involve an expansion of students’ linguistic knowledge by teaching them more than a language, yet it has also been noticed that ESLSCA doesn’t offer any language courses. Moreover, the majority of lectures are conducted in Arabic and English despite the desire of many students that English be used as the medium of instruction as voiced in the interviews.

With regard to the educational background of most students, it was noticed that the two students with a humanities and social sciences background regard the content of most courses at ESLSCA lacking in depth and practical value. The same content is offered to all students regardless of whether they work in the field of manufacturing or services, and no hands-on practice is observed. Respondent four confirmed that most of the professors have either a medical or business background. This contradicts with the results of the study of Morrison et al. (2006) which confirms that selecting academic staff from various disciplines is essential for the success of a cultural diversity course and climate. Furthermore, it was observed that most MBA students take on the degree as a step towards getting promoted at work and, as such, have no motivation to seek research opportunities or enhance analytical or methodological skills. This is another factor hindering any development, study or investigation of cultural diversity cases because individual habits are one of two main components for deciding the human resources’ responses to education and training (Julius, 2000).

From what has preceded, it can be concluded that there is hardly any understanding of the meaning of cultural diversity in ESLSCA-Egypt branch.

Conclusion

Although the website of ESLSCA business school reveals that openness to and encouragement of cultural diversity is a main part of the educational philosophy of this school, the researchers, having carefully investigated the practices, learning environment, and educational components of ESLSCA-Egypt, can confirm that they could not find evidence of any planned or systematic approach by ESLSCA-Egypt to consider, support and/or promote cultural diversity as a part of its curricula or even as a climate the school is committed to create.

It is evident that ESLSCA-Egypt does not fully realize its institutional role in the area of cultural diversity. This role should be both educational and social, driven by the tendency to build the managerial capabilities of its students as well as their political, economic, societal and cultural concerns. However, the interviews have shown that there is a lack of understanding of the concept cultural diversity. The majority of interviewed students together with the board member have defined it as differences in religion and gender although, and as mentioned earlier, cultural diversity has expanded to include much more differences such as educational background, social class, income, work experience, and so on. The school board thinks that, given the fact that the school is French and is providing a mix of English and Arabic educational programs, it reflects a case of valuing and managing cultural diversity. Consequently, the entire content of its MBA curricula neglects, to a maximum degree, the aspects of cultural diversity. Moreover, it completely ignores the hot issues occupying the Egyptian street currently, such as women empowerment, youth empowerment, class inequality, persecution of religious figures, and so on. In fact, the researchers have found that the whole educational content of ESLSCA-Egypt aims to provide a detailed theoretical knowledge base of various business aspects (e.g., strategic management, marketing, economics, accounting and business research).

Finally, ESLSCA-Egypt fails to integrate cultural diversity into its management policies. ESLSCA- Egypt has not arranged any initiatives (e.g., training, coaching, mentoring, etc.) to equip its students with the values of cultural diversity (inclusion, tolerance, solidarity, equality, etc.).

This may reflect that the school is not fully aware of the status of division threatening the society which it serves, on the one hand, and it isn’t completely aware of how to support its students in an updatable academic and professional way, on the other.

References

- AACSB: Association to advance collegiate schools of business. (2004). Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accreditation (Rev. ed).

- Alzaroo, S. & Hunt, G. (2003). Education in the context of conflict and instability: the Palestinian case, Social policy and administration, 37 (2), 165-180.

- Bauer, P. (2011). The transition of Egypt in 2011: A New Springtime for the European Neighborhood policy, Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 12 (4), pp. 420-439.

- Codling, A. & Meek, L. (2006). Twelve propositions on diversity in higher education. Higher education management and policy, OECD, 18 (3), pp. 1-25.

- Davis, P. (2005). Enhancing multicultural harmony: ten actions for managers, Nursing management, 26 (7).

- Dogra, N. (2001). The development and evaluation of a program to teach cultural diversity to medical undergraduate students, Medical education, 35, pp. 232-241.

- ESLSCA MBA. Available at: http://www.eslsca.org/web/Why%20MBA.aspx.

- ESLSCA philosophy. Available at: http://www.dirige.eslsca.fr/aboutus/advantage/advantage.htm.

- Fenwick, M., Costa, C. & D’netto, B. (2011). Cultural diversity management in Australian manufacturing organizations, Asia pacific journal of human resources, 49 (4).

- Gay, G. (2013). Teaching to and through cultural diversity, Cultural diversity and multicultural education, 43 (1), pp. 38-70.

- Grobler, B.R., Moloi, K.C., Loock, C.F., Bisschoff, T.C. & Mestry, R.J. (2006).Creating a School Environment for the Effective Management of Cultural Diversity, Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 34 (4).

- Hargreaves, E. (2001). Profiles of educational assessment systems world-wide: Assessment in Egypt, Assessment in Education, 8 (2), pp. 247-260.

- Hartei, C. (2004). Towards a multicultural world: identifying work systems, practices and employee attitudes that embrace diversity, Australian journal of management, 29 (2).

- Heuberger, В., Gerber, D. & Anderson, R. (2010). Strength through Cultural Diversity: Developing and Teaching a Diversity Course, College Teaching, 47 (3), pp. 107-113.

- Hofstede, G. & Hofstede, G.J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. McGraw Hill.

- Humphrey, N., Bartolo, P., Ale, P., Calleja, C., Hofsaess, T., Janikofa, V., Lous, M., Vilkiene, V. &Westo, G. (2006). Understanding and Responding to diversity in the primary classroom: an international study, European Journal of Teacher Education, 29 (3), pp. 305-313.

- Julius, D. (2000). Human Resources. New directions for higher Education. (111).

- Kormanik, M. & Rajan, H. (2010). Implications for diversity in the HRD curriculum drawn from current organizational practices on addressing workforce diversity in management training, Advances in developing Human resources, 12 (3), pp. 367-384.

- Mahrous, A. & Kortam, W. (2012). Students’ evaluations and perceptions of learning within business schools in Egypt, Journal of Marketing for higher education, 22 (1), pp. 55-70.

- Misra, S. & McMahon, G. (2006). Diversity in higher education: the three Rs, Journal of education of business, 40-43.

- Morrison, M., Lumby, J. & Sood, K. (2006). Diversity and diversity management: Messages from recent research, Educational management administration and leadership, 34 (3), pp. 227-295.

- Ogbonna, E. & Harris, L. (2006). The dynamics of employee relationships in an ethnically diverse workforce, Human relations, 59 (3), pp. 379-407.

- Roberson, L., Kulik, C. & Pepper, M. (2001). Designing effective diversity training: influence of group composition and trainee experience, Journal of organizational behavior, 22, pp. 871-885.

- Roberson, Q. and Park, H. (2007). Examining the link between diversity and firm performance, Group and organization management, 32 (5), pp. 548-568.

- Soliman, H. & Abd Elmegied, H. (2010). The challenges of modernization of social work education in developing countries: the case of Egypt, International social work, 53 (1), pp. 101-114.

- Vuuren, H., Westhuizen, P. & Walt, V. (2012). The management of diversity in schools - a balancing act, International Journal of Education Development, 32, pp. 155-162.

- World Bank. (2009). Egypt, Arab Rep. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/country/egypt-arab-republic.

- Zanoni, P., Janssens, M., Benschop, Y. & Nkomo, S. (2009). Unpacking diversity, grasping inequality: rethinking difference through critical perspectives, Organization, 17 (1), pp. 9-29.

- Zoubir, Y. (2000). Doing Business in Egypt, Thunderbird International Business Reviews, 42 (2), pp. 329-347.