Effect of work motivation and job satisfaction on employee performance: Mediating role of employee engagement

Опубликована Авг. 20, 2021

Последнее обновление статьи Дек. 12, 2022

Abstract

Technological developments are things that must be followed by companies to achieve a competitive advantage to improve performance. To achieve and improve performance, companies need active employee engagement by encouraging motivation and fulfilling their job satisfaction. This study aims to analyze the effect of motivation and job satisfaction on performance with employee engagement as a mediating variable. The research sample is Information Technology (IT) companies located in the cities of Jakarta and Bandung, Indonesia. Research respondents are system developers who handle system development activities for a project or part of an ongoing project. By using the convenience sampling technique 103 responses were obtained from IT developers. The research model analysis method uses Partial Least Square (PLS) with SMART PLS Ver 3.0 software. Empirical findings prove that motivation has a positive effect on the performance of IT employees, while job satisfaction is independent. Employee engagement does not directly affect employee performance, but the effect of mediation through motivation and job satisfaction can have a significant effect on employee performance. The research findings have managerial implications, in increasing high employee involvement, motivation needs to be encouraged to be more active and innovative, and facilitate the achievement of the desired results

Ключевые слова

Behavior, IT employees, engagement, organizations, management

INTRODUCTION

The rapidly changing business environment, including increasingly fierce competition, requires companies to carry out various strategies to survive. One of the strategies is related to active employee engagement to achieve the best performance. Today organizations face the formidable challenge of how to manage the labor turnover that will be caused by the migration of many industrial workers; meanwhile, the Information Technology (IT) industry relies heavily on the inherent competence of humans, namely system developers. Several previous studies have shown that such massive competitive pressure, high company demands, and work situations have caused a decrease in the motivation of system developers to stay in the company; this is due to a lack of motivation and employee commitment to the organization (Varma, 2017).

Human resource management (HRM) policies and practices should be directed in a manner that is in line with the organizations strategy and employee expectations. Therefore, it is important to study and understand the factors that can motivate and build job satisfaction among employees because employees are a very valuable asset for the company. Company performance will increase if they are actively involved with motivation and job satisfaction. However, getting or maintaining good employee performance is not easy. Managers must understand the case and know how employees are involved in their work because low involvement can affect company performance. There are not a few problems that can be caused by moving a system developer from one company to another; this is due to the transfer of intellectual capital. Gallup Institute data shows that globally, employee engagement is only 15 percent, while 85 percent are not engaged or inactive. The explanation for the deepening “return crisis” lies in demotivating employees due to low support for achieving the best performance in their jobs. Based on the phenomena described above, this study was conducted to examine the effect of motivation and job satisfaction on employee engagement and their impact on employee performance. Therefore, in general, the problem can be formulated with the question “How can job satisfaction and motivation increase employee engagement, and what are the implications for employee performance?”

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.1. Work motivation

Work motivation is an impulse that appears in a person consciously or unconsciously to demand action with a specific goal. It can be an important component, be it in work, education, or lifestyle. Motivational energy can move any job easier and faster. Work motivation theory is usually associated with justification, not ability; that is, some people when compared to others can get the job done well (Dal Borno & Merlone, 2010). Motivation is generally a function of equity in social exchange based on equity theory. With an understanding of organizational truth, employees can be actively involved in the organization. Meanwhile, with the injustice they get, employees reduce their involvement. As a result, employees at work want the organization to restore a balance between their contribution and the work situation (Giauque et al., 2012). Measurement of work motivation determines the goals, behavioral persistence, and work-related intensity desired by the organization (Virgiawan et al, 2021; Arshadia, 2010). Situational stimuli, personal preferences, and also interactions can determine a person’s motivation in pursuing a desired goal. The resulting tendency can be a combination of several incentives based on internal (self-evaluation) and external activities, outcomes, and consequences, each of which is weighted according to personal motives (Barbuto & Story, 2011). Sometimes there can be a conflict between the original intention and the action taken. Therefore, the right balance between intrinsic and extrinsic motivators will help (Farrell & Finkelstein, 2011). Workers are proud enough of their work that every business can reach a certain level and increasing utility is an implied motivation. This assumption can be tested considering that the utility of choice can be a quadratic function of working hours (Kattenbach et al., 2010). There is a difference between the terms motive and motivation, where the term motive is used in certain contexts in everyday language. Psychologists use this term in general terms describing people, who are thought to have a motive for everything they do (Yurchisin & Park, 2010). The emergence of worker motivation can be observed with some of the new task-oriented approaches to goals, whereas others perform tasks in any way to get good grades or avoid bad prejudice from others (Reio & Ghosh, 2009; Ryan, 2010). If contemplated together, there are three motivational perspectives used (the value of hope, hope, and self-determination), which show that one’s motivation can grow through contextual conditions (Kenny et al., 2010; Setiyani et al., 2020).

1.2. Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction has a very broad definition so that it cannot be seen from just one definition. Happy or positive emotions that result from assessing a person’s work and work experience are also called job satisfaction (Permana et al., 2021; Valentine et al., 2011). The definition given by Tnay et al. (2013) states that job satisfaction is seen as a combination of environmental styles and psychological conditions that can make someone honestly admit satisfaction with the work done. To support this definition, the amount of job satisfaction is represented by what causes the sensation of satisfaction (Darmon, 2011). The essence of job satisfaction is feeling of comfort. During work, job satisfaction becomes unstable, which can be influenced by mood and emotions. Mood states usually last longer, have a causal object and are short-lived. Events at work that trigger emotions are easier to remember than bad moods (Tabarsa & Nazari, 2016). Job satisfaction consists of intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction. Extrinsic job satisfaction includes traits outside of the job itself, for example, pay, the way the company is managed, while intrinsic job satisfaction includes reactions that affect people’s feelings and emotions towards job features related to the job itself, for example, expertise, autonomy, and variety (Spies, 2006). Internal job satisfaction can also be said to be in the form of employee fulfillment and job descriptions (Yurchisin & Park, 2010). Job satisfaction influences organizational citizenship behavior, which is in line with the hypothesis which states that the higher the job satisfaction of the employees, the better the behavior of the workers. Satisfied employees are more likely to speak well of the organization; they are more sensitive to helping coworkers and satisfied employees are more in line with task decisions (Vizano et al., 2021; Husin & Nurwati, 2014). However, dissatisfied workers are reluctant to accept the goals and values of the organization (Wu et al., 2019). It is important to do research related to organizational behavior and work psychology. Psychological research can be evaluated from two different perspectives (Albrech, 2011). First, from a utilitarian perspective, satisfaction should lead to employee behavior that supports organizational functioning (Spies, 2006). Second, from a humanitarian point of view, fair treatment and respect are evidence of the excellent treatment of employees. Job satisfaction can also arise from the need to remain in the organization by choosing a career, learning, and development opportunities (Tnay et al., 2013). Workers have a high commitment to their organization before they develop attitudes such as job satisfaction (Neininger et al., 2010).

Employee job satisfaction significantly determines both forms of perceived fairness. It is the attitude of employees towards various aspects of their work (Choudhary et al., 2013). And it is usually studied in a comprehensive manner, such as when examining the work as a whole or when exploring aspects of a particular task. There are many benefits of job satisfaction, namely the benefits for the organization are providing maximum work productivity and high profitability, while the benefits for workers are fun work, worker participation, control of the work environment, and feeling part of the company’s work environment (Earle, 2003). It cannot be denied that certain characteristics associated with work addiction can have positive implications for workers and organizations, such as job satisfaction, career success, and high labor productivity. In addition, satisfaction is also a reflection of employees’ perceptions of the work done and what roles are assigned to valuable employees. From an organizational perspective, this reflects good job satisfaction and a very supportive organizational climate that leads to employee recruitment and survival. Job satisfaction can even predict the distribution of outcomes at the organizational level, including productivity, turnover and absenteeism rates, service quality, customer satisfaction, and financial performance (Holland et al., 2011). Factors related to supportive personnel management are indirectly related to intention through the mediating effect of job satisfaction (Chang et al., 2013). Performance and job satisfaction that are interrelated are goals that are highly desired by managers. Their relationship is a major focus of diverse studies in organizational behavior and sales management. Understanding of the two main constructs is of interest (i.e., suitability and workplace aggression) because of the previous relationship between these variables. The conflict between these roles is thought to have an impact on job satisfaction. Increased conflict between roles usually leads to decreased job satisfaction (Love et al., 2010). Therefore, satisfaction is very important to predict job satisfaction by showing new relationships between the two while controlling for individual differences and other conceptually relevant variables such as communication and team satisfaction (Rogelberg et al., 2010).

1.3. Employee engagement

In the terminology of “employee engagement” introduced by Gallup Institute, attachment is defined as the status (in a positive sense) of an employee regarding the work environment or the company where he works. The definition of employee engagement varies widely across organizations. Among them is the Caterpillar company, which reveals that engagement is a commitment, morale, and participation of employees who remain in the organization. Employee engagement is the antithesis of job fatigue. Engagement may be an employee’s status that stems from the social exchange at work and ends with higher organizational performance. An employee shows a higher performance when he finds meaning in work, company culture, and policies. Employee involvement is also caused by self-association with job roles, which includes persistence in the workplace, strong involvement in work, and deepening in work activities (Srivastava & Madan, 2016). This is supported by the concept that the psychological experience of the workforce encourages individual attitudes, behavior, and therefore levels of engagement and discharge from work. Margaretha et al. (2021) believes that psychological meaning is an important driver of work engagement. This suggests that the main drivers of total employee engagement are “individual goals and focused energy, adaptability, effects, and persistence directed toward organizational goals” (Albrech, 2011). Engagement above and beyond simple gratification with a utilization arrangement or basic loyalty to the employer - a characteristic nearly all firms have measured over the years. Engagement, on the other hand, is about desire and commitment - the willingness to take one’s place and exert one’s discretionary efforts to help employers succeed (Rai, 2012). In all areas, employee engagement is linked to long-term work, transformations in the way people work, where they work, what they expect from work, and in the workplace. In addition, providing clear communication is important not only for employees to know and process information but also for them to believe that the company is committed to its involvement. Within every engagement, there is an identical pattern: executives, managers, and employees know exactly what’s going on. They know what the problem is, what is not working, where communication, trust, cohesion, harmony, and communication are weak.

To interact with employees, it was decided that a talent management and employee engagement program was needed to help attract, retain, and develop the simplest staff. Then a consultant is obliged to keep detailed written records of how they spent their time during client engagement and new record-keeping procedures for client collections introduced by finance. The impact of technology on job creation and destruction is also a very relevant issue in community motivation and engagement. In general, HR managers use social media because of the convenience and also thanks to the competitive scenario. The use of social media is believed to provide more benefits in the recruitment process, such as broadening the candidate’s background base, both active and passive. Besides that, it also encourages employee interaction and effective collaborative activities, so that mutually beneficial two-way communication is established (Nagendra, 2014). Organizations using force-based interventions have seen significantly higher employee community growth compared to organizational effects groups. Employee involvement shows positive and proactive behavior in the workplace which is a combination of motivational drive and emotionally attached and managers have a high concern for work that is communicated to achieve company goals.

1.4. Employee performance

Performance is an important assessment for companies so that the company’s sustainability can be guaranteed (Zhang, 2010). Employee performance includes behavior that is under control but provides limits for irrelevant behavior (Dewettinck & van Ameijde, 2011). Meanwhile, the performance also assesses the active role of employees in carrying out obligations according to the formal contract given to them by the company (Biswas, 2009). Employee performance is divided into task performance and performance behavior. This behavior involves factors related to work. In the workplace, employee behavior is reflected in instantaneous behavior and extra roles. Behavior also consists of positive and negative behavior. The existence of employee performance appraisals can increase motivation and encourage them to be actively involved in innovative programs, and make it easier to reach the desired goals (Minavand & Lorkojouri, 2013). Employee performance appraisal provides feedback, and programs are prepared to improve performance that can help employees develop skills to maximize their potential (Cascio, 2014; Susanto et al., 2020). Employees with high perceived organizational support (POS) indicate that they have a greater responsibility which collectively helps the organization achieve its goals, increases rewards for key performance, and such employees are highly committed to the organization (Neves & Eisenberger, 2012; Silitonga et al., 2020). Managers and employees may also view performance differently based on cultural and cross-cultural diversity in the definition and interpretation of performance. Thus, with an individualistic culture, stress will affect individual efforts and outcomes, demanding objective and measurable performance criteria. Managers expect much higher performance in both quality and quantity, longer hours, greater responsibility, and less demand for various types of rewards. The company’s business strategy to get the best performance recognizes the need for talented managers who are ready to see opportunities. Therefore, currently, the organization continues to concentrate on implementing HR practices and methods that can create good performance through improving the quality of employees, such as both formal and informal training, compensation, teamwork, career development, and others (Hapsari et al., 2021; Mangaleswaran & Thevanes, 2018). The concept of numerical performance has not been able to explain performance systems and faces obstacles when used for direct qualitative evaluation and requires resources to handle even challenging tasks and situations (Huo, 2012). Managers perform their functions to support people development and employee performance, as well as to enable a positive work context and co-worker relationships. Therefore, a study is needed to ascertain whether having such enthusiasm can also be beneficial for employee performance and what mechanisms are related to passion (Ho et al., 2011). The broader concept encompassing various activities in which organizations seek to assess employees and develop their competencies, improve performance and distribute rewards is the concept of employee performance management (Decramer et al., 2012). Inherent knowledge capacity can be poured into the work so that it can affect employee performance (Smith-Crowe et al., 2003). Such employees are generally anxious about their work, performance, and relationships with coworkers. In addition, some of them have poor performance. Poor performance conditions also weaken resistance to various changes (Liu et al., 2012). Performance management is consistently among the lowest areas. However, performance management is the main process to get the job done. This is how organizations communicate expectations and encourage the behavior to achieve important goals for development programs or other personnel actions.

One example of a management program in carrying out work alignment is to implement a work from the home system for workers, including adjustable working hours, work and rest balance, and suggesting better performance appraisals. Employee performance can be assessed on two scales: performance in roles and assistance as the main dimensions of OCB. Employee performance is assessed by participants and colleagues at work (Yurchisin & Park, 2010; Kattenbach et al., 2010). Companies with high commitment and high performance are ready to provide sustainable performance because they need to develop the next organizational pillars: 1. Performance alignment; 2. Psychological harmony; and 3. Capacity to learn and change.

2. HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Based on an in-depth literature review, empirical evidence shows contradictory findings on the impact of motivation and job satisfaction on employee engagement and their implications for employee performance. Therefore, the hypotheses to be tested in the study are as follows:

H1: Work motivation affects employee performance.

H2: Job satisfaction affects employee engagement.

H3: Motivation and job satisfaction through employee engagement affect employee performance.

3. AIMS AND METHODOLOGY

The objective of this study is to prove empirically that motivation and job satisfaction can increase employee engagement and have implications for achieving optimal employee performance.

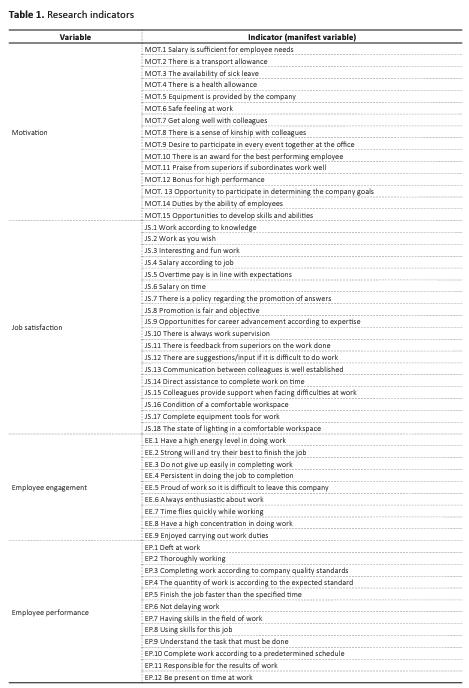

The stages of the study process were first carried out by collecting data according to the tested variables obtained through surveys. This study uses qualitative data quantified with a Likert scale of 1-5, with research variables consisting of motivation, job satisfaction, employee engagement, and employee performance. The following is an explanation of these variables. This study was conducted on IT companies in Indonesia, with respondents who are system developers who handle system development activities for a project or part of an ongoing project. The study was conducted from January 2020 to May 2020. The locations of the companies studied were Jakarta and Bandung. The number of respondents in this study was 103 IT developers who were carried out using the convenience sampling method. The analysis used is Partial Least Square (PLS) using SMART PLS Ver 3.0 software with independent variables of motivation and job satisfaction.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

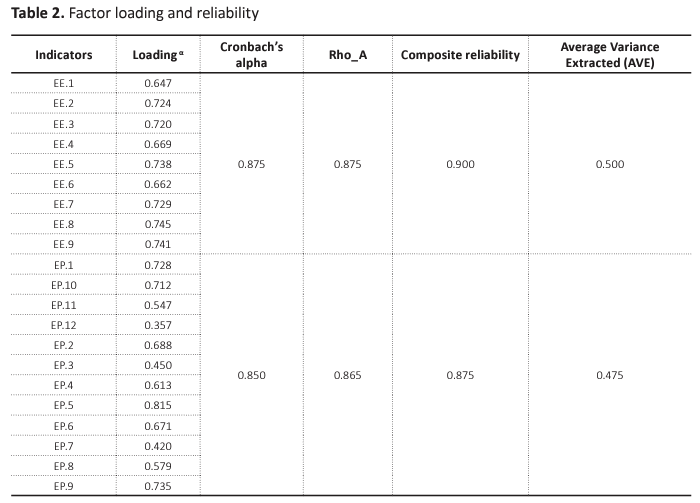

The outer model test results are discussed in the following section which shows the outer loading value using the SmartPLS analysis tool.

4.1. Test validation

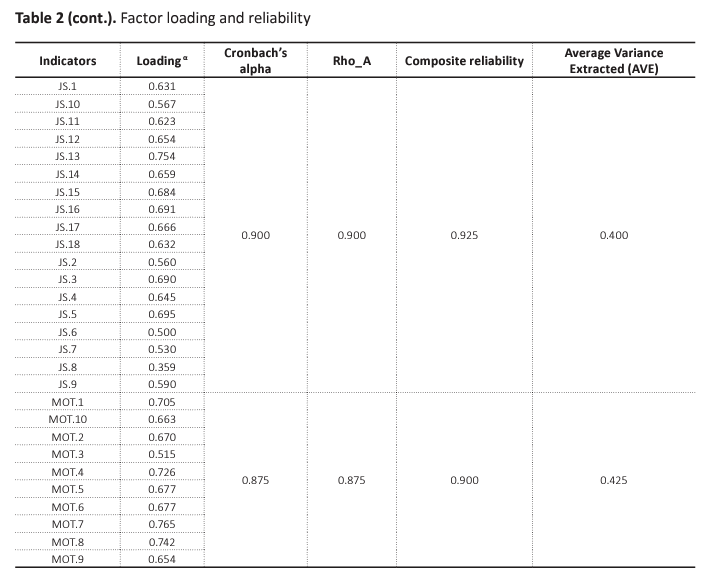

If the loading factor has a value above 0.5 for the construct in question, then the indicator is said to be valid. Table 2 shows the Smart PLS Output for the loading factor.

First, a discussion of the impact of indicators on each variable that has been determined is carried out. In the motivation variable, it can be seen that establishing good socialization with colleagues (MOT.7) has a greater influence on motivation by 0.765, and MOT.3 (presence of sick leave) has a small effect, namely 0.515. 2. At the point of job satisfaction, communication between colleagues that goes well (JS.13 = 754) has a major effect on job satisfaction, while the existence of objective promotion (JS.8 = 359) is the smallest point in improving job satisfaction. Employee involvement with a high concentration in doing work (EE.8 - 0.745) has a major effect on employee engagement, whereas EE.l - 0.647. The high energy level in doing work is the lowest indicator in influencing employee engagement. Furthermore, the results of the analysis for each variable reflect that motivation has a positive effect on the formation of employee performance when compared to job satisfaction and employee engagement with a value of 0.437, then job satisfaction with a value of 0.319, and finally employee engagement of 0.193. According to Table 2, there is still an indicator effect on each variable below 0.5, namely:

- 8 with a value of 0.359

- 12 with a value of 0.357

- 7 with a value of 0.420

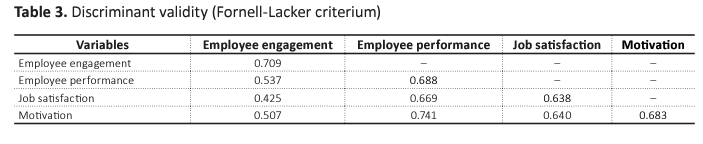

After modifying the indicators, JS.8, EP.12, and EP.7 are no longer done. The value of the loading factor of motivation increased to 0.459 for employee performance, while the value of work performance decreased to 0.301, and the value of employee engagement decreased to 0.176. However, to see discriminant validity Fornell- Lacker criterium values that are above 0.5, only employee engagement. Therefore, the variables tested other than employee engagement was not reliable or did not meet the criteria for convergent validity.

Table 3 states that the square root of the AVE for each construct has a value greater than the correlation value, so the construct of this research model is said to have good discriminant validity.

4.2. Reliability test

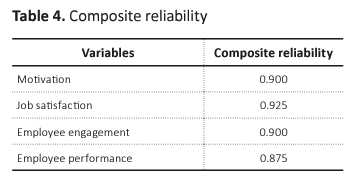

The reliability test is useful for calculating the composite reliability value of the indicator block that measures the construct. The results of the composite reliability calculation get a satisfactory value if it exceeds 0.7. The composite reliability values for the output are shown in Table 4.

The calculation results show that all variables meet the desired composite reliability value, which is above 0.7, which means that all variables are realistic.

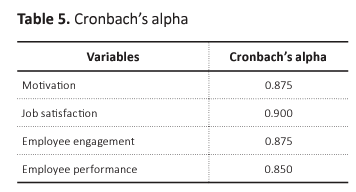

Table 5 shows the recommended value is above 0.6, where Cronbach’s alpha > 0.6 and the lowest value is 0.850 meaning that it meets the desired criteria.

4.3. Structural model testing (inner model)

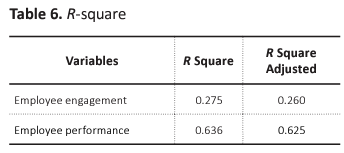

The estimated model meets the performance of the outer model, then the next step is to test the structural model (inner model). The value of R-Square in the construct is shown in Table 6.

The results show that the variables of motivation and job satisfaction affect employee performance by 63.60%, while employee engagement is not very influential.

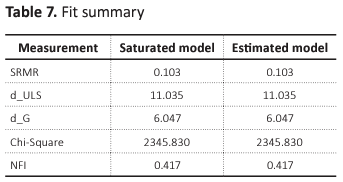

Hypothesis is accepted or rejected based on the significance value between the constructs, t-statis- tics, and p-values. With the test results, standard errors and measurement estimates are no longer calculated based on statistical assumptions but depend on empirical observations. In the bootstrap resampling method, the hypothesis is accepted if the significance value of t-value is greater than 1.96 andp-value is less than 0.05 then the hypothesis is accepted, and vice versa.

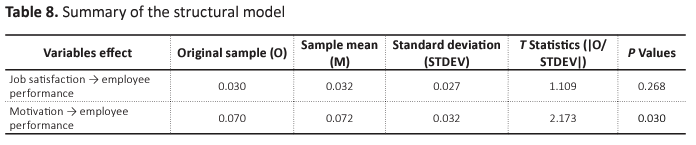

The results of testing the hypothesis of the influence of motivation (Hl) and job satisfaction (H2) on performance are shown in Table 8. Table 8 shows that job satisfaction does not affect employee performance where the t-statistic value is 1.109 (< 1.96). The estimated value of the original sample is 0.030 that indicates the relationship between motivation and employee performance is positive. The probability value obtained is 0.268 (< 0.05). Thus, H2 is rejected: there is no effect of job satisfaction on employee performance. Table 8 shows that motivation affects employee performance where the t-statistic value is 2.173 (> 1.96). The estimated value of the original sample is 0.070 that indicates the relationship between motivation and employee performance is positive. The probability value obtained is 0.030 (< 0.05). So, Hl is accepted: there is an influence of motivation on employee performance. Testing the effect of employee engagement mediation on performance (H3) is shown by the structural model in Figure 3 where the value of t-statistics is based on the output with Smart PLS.

Based on Table 2, the results of the analysis show that the overall indicator value is above 5. Now the indicator can influence the variable. First, for the motivation variable, the highest indicator is MOT.7, and the lowest is MOT.3. Second, regarding job satisfaction, the highest indicator is JS.13, and the lowest is JS.6. Third, for employee engagement, the highest indicator is EE.9, and the lowest is EE.4. Fourth, regarding employee performance, the highest indicator is EP.5, and the lowest is EP. 11. So it can be said that motivation has a more significant influence on employee engagement when compared to job satisfaction. Then employee performance is more significant and positively influenced by motivation with a value of 6.972, then job satisfaction with a value of 3.619, and the smallest is employee engagement with a value of 2.274.

CONCLUSION

Empirical findings proved that the motivation variable has a positive effect on employee performance variables; on the other hand, job satisfaction does not have any impact. Motivation and job satisfaction have a positive and significant effect on employee performance. The direct involvement of workers does not affect employee performance, but mediating the effect through motivation and job satisfaction can significantly affect employee performance. The results of this study provide recommendations for company management, in increasing high employee engagement, employee motivation needs to be encouraged to be more active and innovative, and facilitate the achievement of desired results, reviews generate feedback, and performance improvement plans help employees develop skills that maximize their potential. The organization communicates expectations and encourages personnel behavior to achieve important goals for the development program so that personnel who have this passion can benefit from employee performance. Active employee involvement needs to be encouraged to provide job satisfaction and motivation according to employee expectations so that passion for work is high and performance achievement can be optimal.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Setyo Riyanto.

Data curation: Novita Herlisha.

Formal analysis: Endri Endri, Novita Herlisha.

Funding acquisition: Setyo Riyanto.

Investigation: Novita Herlisha.

Methodology: Novita Herlisha.

Project administration: Setyo Riyanto, Endri Endri.

Resources: Setyo Riyanto, Endri Endri.

Software: Novita Herlisha.

Supervision: Setyo Riyanto.

Validation: Endri Endri.

Visualization: Novita Herlisha.

Writing - original draft: Novita Herlisha.

Writing - review & editing: Endri Endri.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was made possible because of the full support of the Region III Education Service Institute (LL-DIKTI III), the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia, and the Research Center at Mercu Luana University, Jakarta.

REFERENCES

- Albrech, S. L. (2011). Handbook of Employee Engagement: Perspectives, Issues, Research, and Practice. Human Resource Management International Digest, 19(7), 176-178.

- Arshadia, N. (2010). Basic need satisfaction, work motivation, and job performance in an industrial company in Iran. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1267-1272.

- Barbuto, J. E., & Story, S. P. J. (2011). Work Motivation and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Journal of Leadership Studies, 5(1), 23-34.

- Biswas, S. (2009). HR practices as a mediator between organizational culture and transformational leadership: Implications for employee performance. Psychological Studies, 54(2), 114-123.

- Cascio, W. F. (2014). Leveraging employer branding, performance management, and human resource development to enhance employee retention. Human Resource Development International, 17(2), 121-128.

- Chang, W.-J. A., Wang, Y.-S., & Huang, T.-C. (2013). Work design-related antecedents of turnover intention: a multilevel approach. Human Resource Management, 52(1), 1-26.

- Choudhary, N., Kumar, R., & Philip, P. (2013). Links between Organisational Citizenship Behaviour, Organisational Justice, and Job Behaviours at the Workplace. LBS Journal of Management & Research, 11(2), 3-11.

- Dal Forno, A., & Merlone, U. (2010). Incentives and individual motivation in supervised workgroups. European Journal of Operational Research, 207(2), 878-885.

- Darmon, R. Y. (2011). Processes underlying the development and evolution of salespersons’ job satisfaction/dissatisfaction: A conceptual framework. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 28(4), 388-401.

- Decramer, A., Smolders, C., Vanderstraeten, A., & Christiaens, J. (2012). The Impact of Institutional Pressures on Employee Performance Management Systems in Higher Education in the Low Countries. British Journal of Management, 23(S1), S88-S103.

- Dewettinck, K., & van Ameijde, M. (2011). Linking leadership empowerment behaviour to employee attitudes and behavioural intentions: Testing the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Personnel Review, 40(3), 284-305.

- Earle, H. A. (2003). Building a workplace of choice: Using the work environment to attract and retain top talent. Journal of facilities management, 2(3), 244-257.

- Farrell, S. K., & Finkelstein, L. M. (2011). The Impact of Motive Attributions on Coworker Justice Perceptions of Rewarded Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(1), 57-69.

- Giauque, D., Ritz, A., Varone, F., & Anderfuhren-Biget, S. (2012). Resigned but satisfied: The negative impact of public service motivation and red tape on work satisfaction. Public Administration, 90(1), 175-193.

- Hapsari, D., Riyanto, S. & Endri, E. (2021). The Role of Transformational Leadership in Building Organizational Citizenship: The Civil Servants of Indonesia. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(2), 595-604.

- Ho, V. T., Wong, S. S., & Lee, C. H. (2011). A Tale of Passion: Linking Job Passion and Cognitive Engagement to Employee Work Performance. Journal of Management Studies, 48(1), 26-47.

- Holland, P., Pyman, A., Cooper, B. K., & Teicher, J. (2011). Employee voice and job satisfaction in Australia: the centrality of direct voice. Human Resource Management, 50(1), 95-111.

- Huo, B. (2012). The impact of supply chain integration on company performance: An organizational capability perspective. Supply Chain Management, 17(6), 596-610.

- Husin & Nurwati. (2014). The Role of Accounting Information, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment to Job Performance through Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) (Studies in Small and Medium Enterprises in Southeast Sulawesi). IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16(11), 25-31.

- Kattenbach, R., Demerouti, E., & Nachreiner, F. (2010). Flexible working times: Effects on employees’ exhaustion, work-nonwork conflict, and job performance. Career Development International, 15(3), 279-295.

- Kenny, M. E., Walsh-Blair, L. Y., Blustein, D. L., Bempechat, J., & Seltzer, J. (2010). Achievement motivation among urban adolescents: Work hope, autonomy support, and achievement-related beliefs. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 205-212.

- Liu, Y., Valenti, M. A., & Yu, H.-Y. (2012). Presuccession performance, CEO succession, top management team, and change in a firm’s internationalization: The moderating effect of CEO/chairperson dissimilarity. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 29(1), 67-78.

- Love, K. M., Tatman, A. W., & Chapman, B. P. (2010). Role stress, inter-role conflict, and job satisfaction among university employees: The creation and test of a model. Journal of Employment Counseling, 47(1), 30-37.

- Mangaleswaran, T., & Thevanes, N. (2018). Relationship between Work-Life Balance and Job Performance of Employees. IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 20(5), 11-16.

- Margaretha, M., Saragih, S., Zaniarti, S., & Parayow, B. (2021). Workplace spirituality, employee engagement, and professional commitment: A study of lecturers from Indonesian universities. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 19(2), 346-356.

- Minavand, H., & Lorkojouri, Z. (2013). The linkage between strategic human resource management, innovation, and firm performance. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 11(2), 85-90.

- Nagendra, A. (2014). Paradigm Shift in HR Practices on Employee Life Cycle Due to the Influence of Social Media. Procedia Economics and Finance, 11, 197-207.

- Neininger, A., Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., Kauffeld, S., & Henschel, A. (2010). Effects of the team and organizational commitment – A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(3), 567-579.

- Neves, P., & Eisenberger, R. (2012). Management Communication and Employee Performance: The Contribution of Perceived Organizational Support. Human Performance, 25(5), 452-464.

- Permana, A., Aima, M. H., Ariyanto, E., Nurmahdi, A., Sutawidjaya, A. H., & Endri, E. (2021). The effect of compensation and career development on lecturer job satisfaction. Accounting, 7(6), 1287-1292.

- Rai, S. (2012). Engaging Young Employees (Gen Y) in a Social Media Dominated World – Review and Retrospection. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 37, 257-266.

- Reio, T., & Ghosh, R. (2009). Antecedents and Outcomes of Workplace Incivility: Implications for human resource development research and practice. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 20(3), 237-264.

- Rogelberg, S. G., Allen, J. A., Shanock, L., Scott, C., & Shuffler, M. (2010). Employee satisfaction with meetings: a contemporary facet of job satisfaction. Human Resource Management, 49(2), 149-172.

- Ryan, J. C. (2010). An examination of the factor structure and scale reliability of the work motivation scale, the motivation sources inventory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(6), 1566-1577.

- Setiyani, A., Sutawijaya, A., Nawangsari, L.C., Riyanto, S., & Endri, E. (2020). Motivation and the Millennial Generation. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 13(6), 1124-1136.

- Silitonga, T. B., Sujanto, B., Luddin, M. R., & Susita, D., & Endri, E. (2020). Evaluation of Overseas Field Study Program at the Indonesia Defense University. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity, and Change, 12(10), 554-573.

- Smith-Crowe, K., Burke, M. J., & Landis, R. S. (2003). Organizational climate as a moderator of safety knowledge-safety performance relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(7), 861-876.

- Spies, M. (2006). Distance between home and workplace as a factor for job satisfaction in the North-West Russian oil industry. Fennia, 184(2), 133-149.

- Srivastava, S., & Madan, P. (2016). Understanding the Roles of Organizational Identification, Trust, and Corporate Ethical Values in Employee Engagement–Organizational Citizenship Behaviour Relationship: A Study on Indian Managers. Management and Labour Studies, 41(4), 314-330.

- Susanto, Y., Nuraini, Sutanta, Gunadi, Basrie, Mulyadi, & Endri, E. (2020). The Effect of Task Complexity, Independence and Competence on the Quality of Audit Results with Auditor Integrity as a Moderating Variable. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity, and Change, 12(12), 742-755.

- Tabarsa, G., & Nazari, A. J. (2016). Examining the moderating role of mentoring relationship in-between content plateauing with job satisfaction and willingness to leave the organization (case study: Iran ministry of industry, mines, and trade). Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 9(7), 1-8.

- Tnay, E., Othman, A. E. A., Siong, H. C., & Lim, S. L. O. (2013). The Influences of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment on Turnover Intention. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 97, 201-208.

- Valentine, S., Godkin, L., Fleischman, G. M., & Kidwell, R. (2011). Corporate Ethical Values, Group Creativity, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention: The Impact of Work Context on Work Response. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(3), 353-372.

- Varma, C. (2017). Importance of Employee Motivation & Job Satisfaction for Organizational Performance. International Journal of Social Science & Interdisciplinary Research, 6(2), 10-20.

- Virgiawan, A. R., Riyanto, S., & Endri, E. (2021). Organizational Culture as a Mediator Motivation and Transformational Leadership on Employee Performance. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 10(3), 67.

- Vizano, N. A., Sutawidjaya, A. A., & Endri, E. (2021). The Effect of Compensation and Career on Turnover Intention: Evidence from Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 8(1), 471-478.

- Wu, T., Shen, Q., Liu, H., & Zheng, C. (2019). Work Stress, Perceived Career Opportunity, and Organizational Loyalty in Organizational Change: A Moderated Mediation Model. Social Behavior and Personality, 47(4), 1-11.

- Yurchisin, J., & Park, J. (2010). Effects of retail store image attractiveness and self-evaluated job performance on employee retention. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 441-450.

- Yurchisin, J., & Park, J. (2010). Effects of retail store image attractiveness and self-evaluated job performance on employee retention. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 441-450.

- Zhang, J. (2010). Employee Orientation and Performance: An Exploration of the Mediating Role of Customer Orientation. Journal of Business Ethics, 91, 111-121.