Ethno- medicine of Bhotia tribe in Mana village of Uttarakhand

Опубликована Окт. 30, 2014

Последнее обновление статьи Авг. 21, 2022

Abstract

The present paper is based on field work conducted in village Mana in Joshimath subdivision of the District Chamoli, Uttarakhand, among Bhotias. The group of Bhotias residing in this village belongs to the Marcha Bhotia category and is transhumant in nature. The paper gives an ethnographic background of the Bhotias and then focuses on the major ethno-medicines which are used by these people. These medicines have been in use through the ages. This traditional knowledge is of significance since the health services in this region are limited and these medicines are effective in curing patients. The intellectual property right of these medicines belongs to these people and they must be given the credit for it.

Ключевые слова

Ethno-medicine, Mana village, traditional knowledge., Bhotias

INTRODUCTION

Area and the people

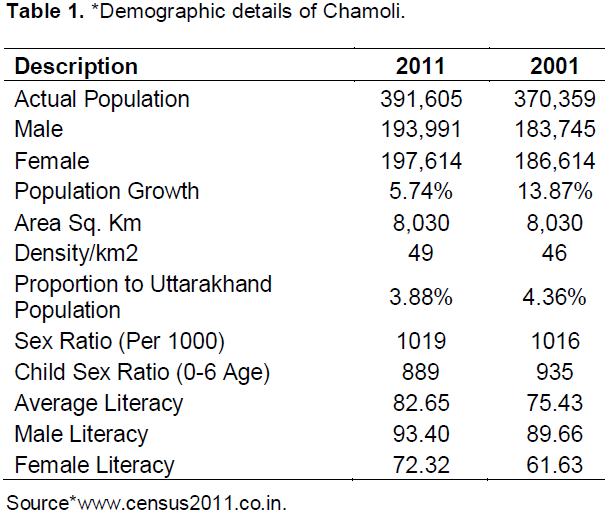

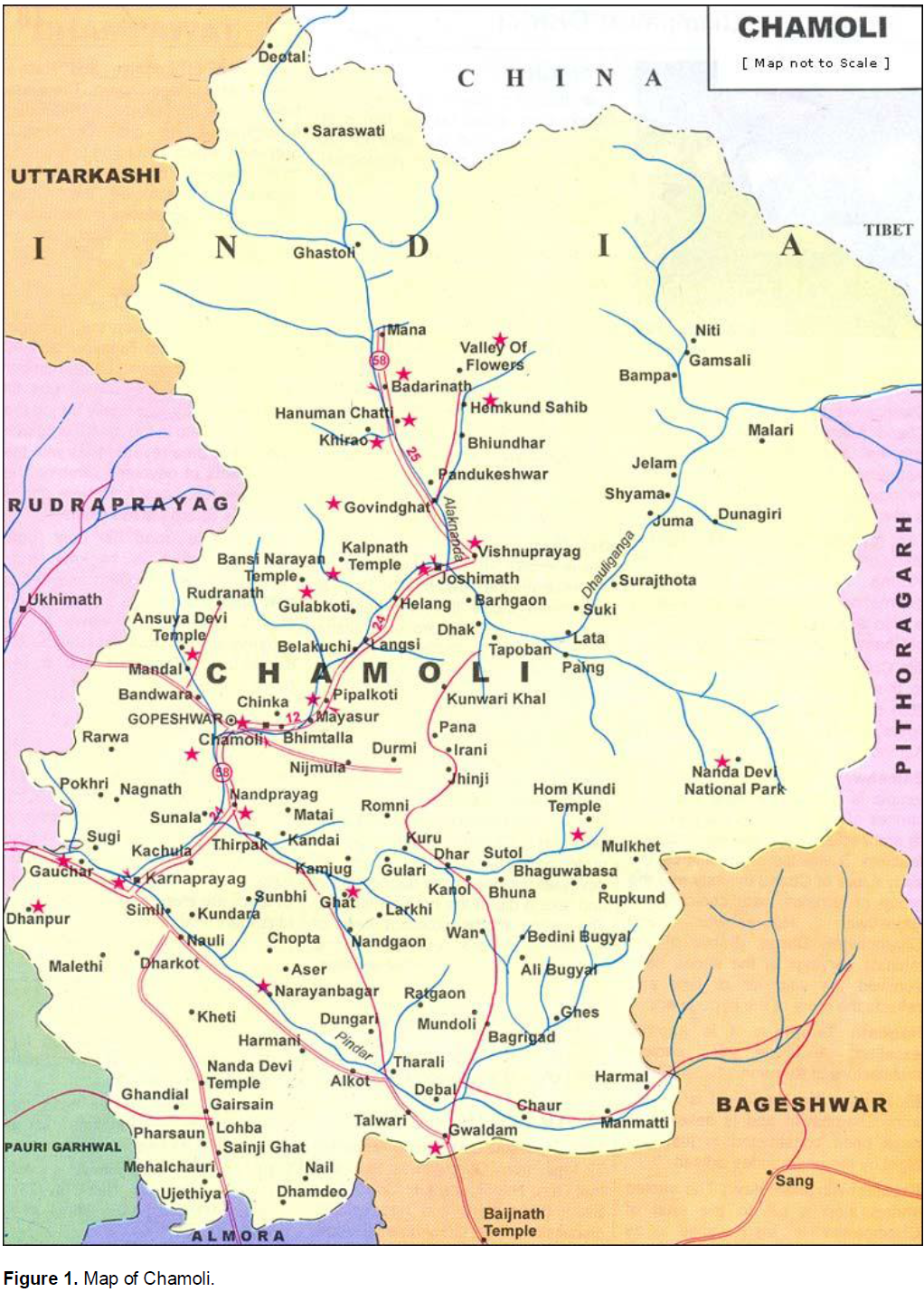

Mana village is situated on the bank of River Saraswati. It is a part of Tehsil Joshimath in the District Chamoli. Mana is situated at an elevation of 10,510 feet above sea level. The population is constituted by Marcha Bhotias. There are a few houses of Harijans also. Mana is the last village on the Indian side of the International border between India and China in the Himalayan state of Uttaranchal. It is the last village on the Indian side where people cultivate the land. Mana is covered by snow for about six months and the people living there go down to villages situated in lower altitude. This movement occurs approximately from 16th November onwards. They return to the higher altitudes in the month of May, in the summer season, when the glaciers start melting (Table 1).

According to 2001 census, village Mana which falls in Joshimath sub-division had 188 houses with the total population being 594. Out of this, there were 254 males and 340 females. 395 people were educated, 207 of them were males and 188 were females. Among the uneducated population 47 were males and 152 were females. The researcher found during the present study that the women were taking interest in education and would like to get a job as a teacher if it would be offered to them in their own area. The younger Bhotias were found to be taking interest in education, but they were more interested in doing government jobs. Before the partition of the state of Uttar Pradesh in Uttaranchal and U.P. (2000), the Bhotia were given the special status of a Schedule-Tribe (ST) by the government of India in 1967. Now Mana also has been given the status of a Heritage Village. Due to their special status, education, awareness of government policy and comradery among themselves the Bhotias have always received concessions from the government and benefits of the reservation policy of India. Undoubtedly the Bhotias have a better Socio-Economic standard of living compared to the Non-Scheduled castes of the Garhwalis in their neighborhood. By tradition they were used to traveling and indulging in fruitful economic activities and trade across the border which was banned by the government later on in 1962. Those Bhotias who are engaged in service are not able to return to their village, frequently. They come only on special occasions and festivals, like marriages and Sankrant (Figure 1).

The Bhotia people are monogamous. They do not practice widow-remarriage. There are some cases of love marriage outside their community, but mostly, they are endogamous. They were earlier living in joint families but now their families are changing into small nuclear families.

They are subdivided into the following sub-castes (as enumerated by themselves): Badwal, Parmar, Pankholi, Rawat, Bisht, Daliya, Molpha, Chauhan, Takola, Jitwan and Kandari.

Their chief God is called ‘Ghant?karna’. Besides, they have their own goddesses for each sub-caste like ‘Nanda Bhagwati’ of Pankholi, ‘Bhawani Devi’ of Badwal etc. They have their own temples and priest. They also worship Hindu gods and goddesses. They participate in Hindu festivals like Dussehra and Diwali. Their own special festival is the ‘Jeth Ki Sankrati’, which occurs in June, when the gates of Ghant?karna temple are opened and sacrifices and worships are offered.

They practice seasonal migration in winter (from mid-November to April); they go down to Ghinghran, Negwad and Lambaggad villages in and around Gopeshwar. In summer (from May to mid-November) they go up to Mana village near Badrinath. Mana village is the last village on the Indian side of the international border. In Mana (their summer home) they cultivate potato, a few vegetables, beans and mustard. They sell woolen carpets and sweaters. In winter, they weave woollen carpets on handloom, and knit sweaters to collect for sale in the tourist season. They breed cattle and keep dogs and mules, which they take with themselves when they migrate. They keep small stalls for tourists, pilgrims and other temples.

Before the Chinese occupation of Tibet, the Bhotias used to travel to and trade with Tibet. For centuries Bhotias had trade relations with Tibet to bring salt, borax, animal skins, wool, gold, mules, sheep and goats. After the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1962, this trade was stopped and the migration route across the Indian border was closed. Because of the century old habit of trade and long route of migration, the Bhotias are very strong and hardy people and have the capacity to adapt to tough Himalayan conditions. Now they confine their seasonal migration to Mana in the north and Gopeshwar in the South.

The traditional knowledge of medicines and herbs is now confined to the elders only. The youths of the Bhotia community have no knowledge of the traditional herbs and health treatments. The use of Allopathic medicines is very popular there. There is a Primary Health Centre and Army Camp-health centre in Badrinath. In Gopeshwar there is also a district hospital. The Bhotia use these facilities provided by the government.

If medicines fail, they go to the ‘Puchher’ a sacred priest who has the knowledge of super natural powers. ‘Puchher’ can be the priest of ‘Ghant?karna’ or the priest of any local temple of the goddesses. Bhotia consult these ‘Puchher’ and have a firm belief in their knowledge and skill.

The rules of the Department of Forest and the government policies prohibit frequent exploitation of the forest for herbs and plant. This discourages the Bhotias to make extensive use of these herbal plants. However, they do get a few herbs and use them for some minor illnesses, consulting their elders.

Socio-economic life

The Bhotia people living in Mana call themselves Marcha Bhotia. The Bhotia people of nearby Niti valley also call themselves Marcha. In the neighbouring villages we do not find Bhotia, for example in Báhmani village near Mana there are Gharwali people, belonging to a caste called Duriyal. These people have their settlements near Badrinath temple which is one of the four major dhaam (Hindu pilgrimage center).

During the months of winter, they live in Pandukesh-war, which is at lower altitude. The main characteristic of Bhotia lifestyle is being ‘Transmigrant’. “Transhumance is the seasonal movement of people with their livestock, between fixed summer and winter pastures. In mountainous regions (vertical transhumance), it implies movement from higher pastures in summer to lower valleys in winter. Herders have a permanent home, typically in valleys. Only the herds travel, accompanied by the people necessary to tend them. In contrast, horizontal transhumance is more susceptible to being disrupted by climatic, economic or political change (Blench, 2001).

In the month of May when they come up, they use heavy four wheelers such as Tata Sumo, and other kinds of vehicles for the purpose. They move their animals by road. It takes six to seven days to reach the village of Mana. The eldest member of family walks along the animals and takes halts in the way. They carry their beddings, some eatables and utensils. They cook and eat on their way. All other people come by taxi. It was not the same in previous days. They did not have all these facilities earlier. But now because of Badrinath pilgrimage they get a lot of facilities. They do not bring along their groceries; now they can get it from Badrinath. By September-October their crops are ripped and then they go back downwards after selling their crops till 16th November.

In Mana the people cultivate some vegetables like potato, green peas, beans, cauliflowers, radish and some varieties of lentils and grains like Rajma, Kutu, Phaphar and mustard. Apart from cultivation they also breed cow, oxen and goat. They keep mules and dogs. These animals and cattle also move with them when they migrate from a higher altitude to a lower altitude, and vice versa, with the changing season. This life style of semi-nomadic movement is called ‘Transhumance’. Because of high altitude and six month of snow the climate is mostly cold throughout the year. However, the winter is considered between middle of November to middle of March. From June to September they have rain. The summer season starts from the middle of March and continues through the middle of June.

At that height of trees of the region are both of broad leaves and pointed leaves. Most of the trees there are Pine, Burans, Kharasu, Tun, Tilong, Kail and Fir. The fauna here is constituted by leopard, cheetah, tiger, panther, Himalayan black bear, brown bear, deer, wild dogs, wild goat and sheep.

The Bhotia people live on the border district of Garhwal and Kumaun in Uttaranchal. Bhotias have always been a transhumant community and have migrated up and down the Himalayan hills after every six months. Therefore, they have two houses. The Bhotias of Mana village live in Ghingran, Negwad and Lambaggad in the lower altitudes from middle of November to April. They start coming up to Mana when gates of Badrinath temple are opened for Pilgrimage, in summer months. When they come up to Mana they start cultivating grains, potato and other vegetables. Once planting of crops is completed, these people pay their attention to earning money by selling woolen sweaters, socks, caps, ‘Dun’; carpets, ‘Aasan’ (small carpets for sitting)’; ‘Pankhi’, ‘Shawl’, ‘Lava’ etc. They also keep shops for these things, along with tea shops, where they sell tea and snacks to tourist and pilgrims. Some of them supply milk to other shopkeepers. Sometimes outsiders visit their houses to get local liquor on cash payment. Some people also sell popular herbs for common ailments like hair-loss, stomach ache, head ache, cold and cough. These things allow them to get extra cash from pilgrims and tourist in the summer season. Some Bhotias work as drivers to earn money.

The winter months they spend in weaving and knitting woolen items and carpets. Male and female, old and young know this craft of weaving and knitting beautiful carpets and sweaters.

Many Bhotias go out to big cities like Dehradun, Delhi, Meerut, Kanpur and Lucknow for higher education and jobs. Some of them are also occupying good posts of engineers, doctors, bank managers and teachers. They are also serving in the Indian Army.

Earlier they mostly had joint families, but now since they are going to different places for employment, there are forming more nuclear families.

Bhotias practice monogamy and they do not believe in widow remarriage. Marcha Bhotias do not marry in the same caste, as they take one caste as a family (Exogamous), Earlier Marcha Bhotias were against the marriage with Tolcha Bhotias, but now-a-days there is a trend towards change. Now they also support love marriage and many outside Bhotia community. Although, there are very few cases of such marriage. The age of marriage is around 20-27 years. They get married after they complete there studies and specially boys like to marry only when they are settled with some occupation.

Socio-religious life

The Bhotias of this region have many subdivisions which they call ‘Jatis’. The main subdivisions which they recognize are: Badwal, Paramar, Pankholi, Rawat, Bisht, Dalia, Molpha, Chauhan, Takola, Jitwan and Kandari. They believe that people of Molpha caste are the original inhabitants of village Mana. They have 13 houses of Molphas in this village. Other people are believed to have come here from different neighbouring places. The Harijans living in the village have a similar life style but some of these Harijans serve the Bhotias by doing odd jobs and stitching their clothes.

The main god of Mana people is ‘Ghant?Karna Devta’ who is called ‘Kshetrapal’ by them. This means that he is the protector of this region. Apart from this, all the caste has their own goddesses (Kuldevi) as, Pankholi people worship goddess Nanda Bhagwati, Badwal worship Bhawani Devi, Bisht worship Siddhnath and so on. They have separate temples and priests devoted to different duties. When Bhotia people come to live in Mana, these temples are opened on Sankranti of the month of Jeth (June). After that ceremony, they worship their gods with all the rituals. They believed that the ‘devta’ (deity) comes over the temple priest which means that the priest is possessed by the supernatural power for some time. ‘Ghant?karna Devta’ is offered mainly ‘Jaan’ (a type of raw liquor). Apart from this people offer ‘Prasad’ as per their wishes. A goat is sacrificed to the deity. Anyone whose wish has been fulfilled sacrifices a goat. Normally they offer ‘Halwa’, ‘Kheer’, ‘Puri’ and sometimes a goat also to the goddess (kuldevi). Other than this Bhotias celebrate all the festivals celebrated by Hindus and worship “Brahma’, ‘Vishnu’, ‘Mahesh’ and goddess Durga.

Ethno- medicine

Traditional medicine includes diverse health practices, approaches, knowledge and beliefs. It incorporates plant, animal and/or mineral based medicines, spiritual thera-pies, manual techniques and exercises applied singularly or combined with each other, to maintain well-being as well as to treat, diagnose or prevent illness. ‘Traditional medicine has a long history. It is the sum total of the knowledge, skills and practices based on the theories, beliefs and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health, as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improve-ment or treatment of physical and mental illnesses. The terms complementary/alternative/non-conventional medicine are used interchangeably with traditional medicine in some countries (http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2000/WHO_EDM_TRM_2000.1.pdf?ua=1).

‘Ethno-medicine is a study or comparison of the traditional medicine practiced by various ethnic groups, and especially by indigenous peoples. The word ethnomedicine is sometimes used as a synonym for traditional medicine. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnomedicine).

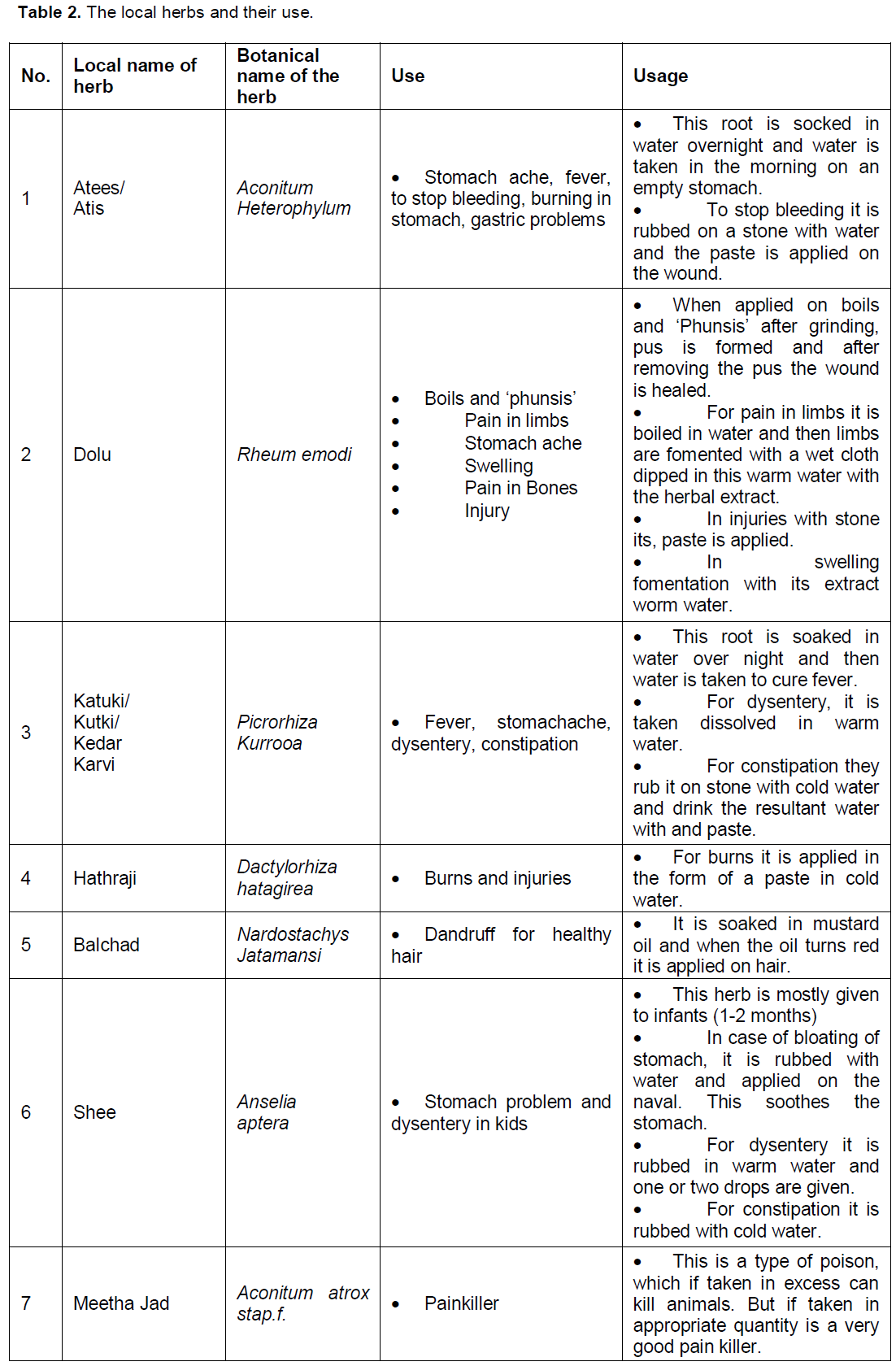

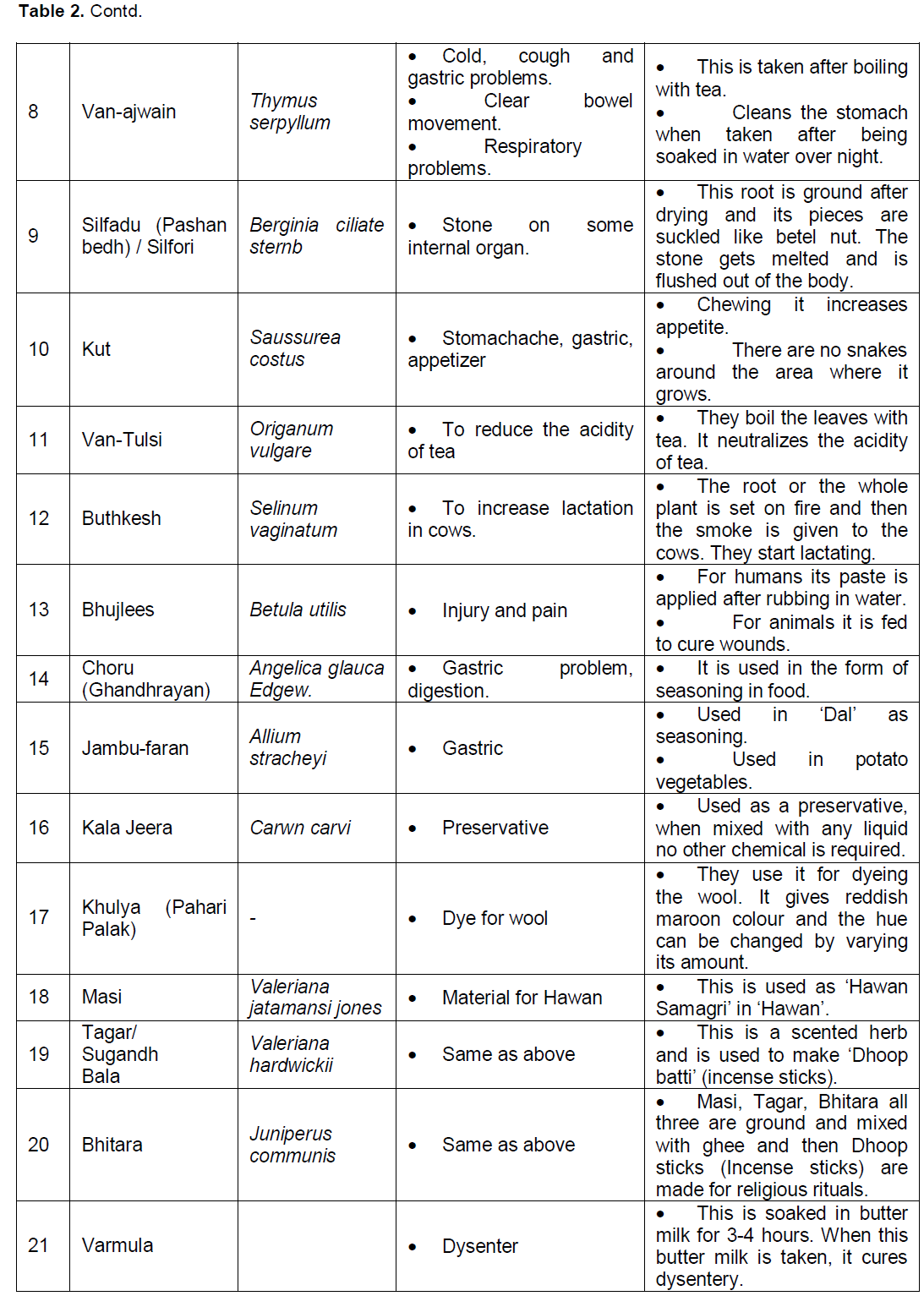

Bhotia people also practice traditional therapies and medicines. Long time back they used to go to the jungle to collect useful medicinal plants and herbs to use them for their treatment. At that time modern medicines were not in use. Nowadays, many elders still know about the medicinal herbs and whenever they get the time and opportunity they collect them from the jungle. The following table contains the names and use of the medicinal plants found here.

METHODOLOGY

The present paper is based on Anthropological fieldwork conducted in Mana Village of Joshimath Sub-division of Chamoli in 2006. We conducted in-depth interviews regarding the indigenous medicine among the Bhotia people of the aforesaid village. Such knowledge was restricted to the older generation. We conducted about 50 interviews. The younger generation showed no inclination in this sphere. We also questioned the respondents regarding the identification of these herbs by actually asking them to show us the samples of them. We explored their use and how it could be made available to the public. Most of these herbs are now being scientifically tested at the Central Herbs Institute (Government of India) at Mandal village of Chamoli (Table 2).

It is important to mention here that in Mana village there are no professional practitioners of folk medicine. All the Bhotia elders know the usage of their traditional medicinal plants. They keep and use them according to their need and convenience. But they do not force any educated youngster to follow these medicines. Being transmigrant and traders, they have a great ability to adapt to changed circumstances, ecology and political scenario. That is why they also have accepted modern medicines and modern education.

Now, they mainly depend on modern medicine. When they live in lower altitudes, they go to Gopeshwar and other hospitals and to the private practitioner for treatment; but when they live in Mana, they go to the Primary Health Centre (PHC) and Army Camp in Badrinath. There, they get free treatment and medicines. They are satisfied with this facility and they depend on it. But serious diseases cannot be cured there. So, when an emergency occurs, they have to go to Gopeshwar. There is no facility of delivery in Badrinath, so pregnant women and mothers of infants do not go to higher altitudes during the summer. These days all the women give birth to their children in hospitals and they also get their vaccination there.

The use of medicinal plants in Bhotias is decreasing and the modern medicines are in vogue. The knowledge of medicinal plants is now restricted to seniors and is on decline. Members of the younger generation neither have the knowledge of these plants nor do they recognize these plants. They are not even interested in gaining the knowledge about it. According to them, when modern medicines are giving fast relief, there is no use of learning these old things. That is why this knowledge is now confined to the older generation of the Bhotia people. Mostly the leaves, flowers or fruits and stem have medicinal value but rarely the root of plants have such medicinal value.

Apart from modern health centers, the Forest Department and Government policies are playing a negative role in the decline of the traditional medicine. As per forest policies, bringing medicinal herbs from jungle is prohibited. The Bhotias have been living here since decades, and they have been using these plants, but now, the younger generation is departing from traditional treatment. Therefore the need of collecting them has also decreased.

Belief in the supernatural power

In the case of any sickness, they first go to Allopathic doctors and use the medicine prescribed by them. But when they find that the treatment is not enough to cure them, they go to ‘Puchher’ a sacred priest, who has the knowledge of the supernatural powers. The ‘Puchher’ can be any spiritual person like a priest of ‘Ghant?karna’ (local deity) or a priest of ‘Kuldevis’. The Bhotia people not only consult instead they have a firm belief in them. When they go to ‘Puchher’, he reveals the cause of their problem. He diagnoses, defining the cause of affliction.

Whether it is ‘Chhaya’/’Bay?l’, ‘Mas?n’ or ‘Edi’, which caused the problem. Afterwards the relevant pooja (ritual) is offered to solve their problems. This pooja is performed by the local priests at the bank of a river or ridge of a mountain. Most of the time their problems are solved and their faith in them is confirmed.

They believe that the main reason behind their sickness is caused by being possessed by a ‘Chhaya’, during their visit to the mountains. It can be cured by interference of a priest or a devta. When the women are lonely on the mountains or in caves, singing or gossiping, they experience the effect of some ‘Chhaya’ (a super-natural presence). They consult the Puchher to get rid of this evil effect which causes them discomfort or illness.

The knowledge of Bhotias is on the verge of extinction and it is our responsibility to save this traditional knowledge of herbal medicines. A lot of projects and researches are being run in Mana and other villages by outsiders. Many people come and gain knowledge but nothing fruitful happens. Bhotias and other tribal groups are the one who have actual and in depth knowledge of traditional medicinal plants and herbs.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our Suggestion is that Bhotian elders should not be stopped from using the forest herbs, so that the traditional knowledge is transmitted to the next generation and perpetuated.

The youths of this ethnic group should be trained to learn their traditional medicine. The Intellectual Property Laws must be amended in India such that the Intellectual Property Rights over ethno-medicines belongs to the locals or natives. ‘Intellectual property rights should guarantee both individual and a group rights to protect and benefit from their own cultural discoveries, creations, and products. But the current IPR system cannot protect traditional knowledge, for three reasons. First, the current system seeks to privatize ownership and is designed to be held by individuals or corporations, whereas traditional knowledge has a collective ownership. Second, this protection is time-bound, whereas traditional knowledge is held in perpetuity from generation to generation. Third, it adopts a restricted interpretation of invention which should satisfy the criteria of novelty and be capable of industrial application, whereas traditional innovation is incremental, informal and occurs over time. An alternative law is therefore necessary to protect traditional knowledge (Bag and Pramanik, 2012). They should also be permitted for the trade of medicinal plants and herbs. It will boost up their economy and thus encourage the perpetuation of the folk medicine among the Bhotias.

If the traditional knowledge is not preserved it shall be lost in the near present. At present the older generation is well-versed in this knowledge, but they are reluctant in disclosing this information to others, especially to ‘outsiders.’ As far as documentation of these ethno-medicines is concerned, the local people are not interested, because they do not realize its worth as an alternative medicine, secondly illiteracy may also be an impediment. ‘The protection of indigenous knowledge has become a major concern and an issue of much debate internationally at organizations such as the United Nations, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the World Intellectual Property Organization. Therefore, developing nations also should promote awareness of indigenous peoples’ rights stemming from their valuable knowledge, and the trustee should invoke trade secret protection whenever possible to prevent the misappropriation and misuse of indigenous peoples’ knowledge. This approach would have several advantages including helping prevent unjust enrichment and cultural theft. Furthermore, indigenous people would be empowered and would have a means to obtain monetary compensation if outsiders misused their knowledge or resources. Indigenous people also would have a means to protect their resources and control the use of their resources (Bag and Pramanik, 2012).

The vast population and the scarce medical facilities increase the need for alternative medical systems. In a state like Uttarakhand the difficult terrain is one of the reasons for lack of medical facilities and paucity of doctors. Hence, here the traditional knowledge systems can be of great help in solving health problems and aid human survival. ‘Revitalizing the traditional healing system, based on native knowledge and resources this is a bottom up approach and shall be enduring. This will help sustain the healthy but fast disappearing native model of traditional healthcare, together with the biodiversity. With the state administered healthcare systems based on modern medicine unable to tackle the mammoth challenges in the country and the acute shortage of resources to effectively target this, the choice before the nation is to practically address the issues on hand. Repositioning the traditions and their delivery systems shall go a long way in this. For knowledge alone is not sufficient there has to be mechanisms to take these to people in a modern society. With policy plans and action modules this can be achieved with minimum expenses for the raw materials are readily available, only it has to be processed and fine tuned where things shall fall in place. But for a huge country like India with its mosaic of cultures and diversities it is no easy task either. Giving uniform guidelines can work only if there are given the space to incorporate the local variations, the herbal medicines used in the Himalayas shall not be the ones used in the coastal regions of India. The large number of traditional healers present in the peninsular tip tribal areas or the North east may not be there in the upper Indian regions. The marked ecosystem and biodiversity variations have to be inbuilt in the policy if it has to achieve the desired results. If the present model is effectively implemented then the results shall be multi-fold better v health of the population, conservation of the rich biodiversity of India and value addition to the presently neglected herbal resources are among these. Recognition to the native healers and their time tested practices shall add to this. In short together with the infrastructure in modern medicine a totally new health-care paradigm shall be available with innate capabilities to complement various sectors of medicine (Pushpangdan and George, 2010).

In order to preserve the ethno-medicine Information and Communication Technology (ICT) can also be used. By using this new technology one can also keep a track of source of information. ‘ICTs can be used to: Capture, store and disseminate indigenous knowledge so that traditional knowledge is preserved for the future generation; Promote cost-effective dissemination of indigenous knowledge; Create easily accessible indigenous knowledge information systems; Promote integration of indigenous knowledge into formal and non-formal training and education; Provide a platform for advocating for improved benefit from IK systems of the poor (Adam, 2007).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

Adam L (2007). Information and Communication Technologies, Knowledge Management and Indigenous Knowledge: Implications to Livelihood of Communities in Ethiopia. | |

| |

Blench R (2001). 'You can't go home again' – Pastoralism in the new millennium. London: Overseas Development Institute. p. 12 | |

| |

Bag M, Pramanik R (2012). Commodification of Indigenous Knowledge: It's Impact on Ethno- medicine, IOSR Journal of Computer Engineering (IOSRJCE) 7(4):08-15. | |

| |

Pushpangdan P, George V (2010). Ethnomedical practices of rural and tribal population of India with special reference to mother and childcare P and V. Indian J. Tradit. Knowledge 9(1):9-17. | |

| |

WHO (2000). General Guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine.WHO/EDM/TRM/2000.1 Distr.: General Original: English. | |