Perceived problems associated with the implementation of the balanced scorecard: evidence from Scandinavia

Опубликована Апрель 1, 2014

Последнее обновление статьи Дек. 8, 2022

Abstract

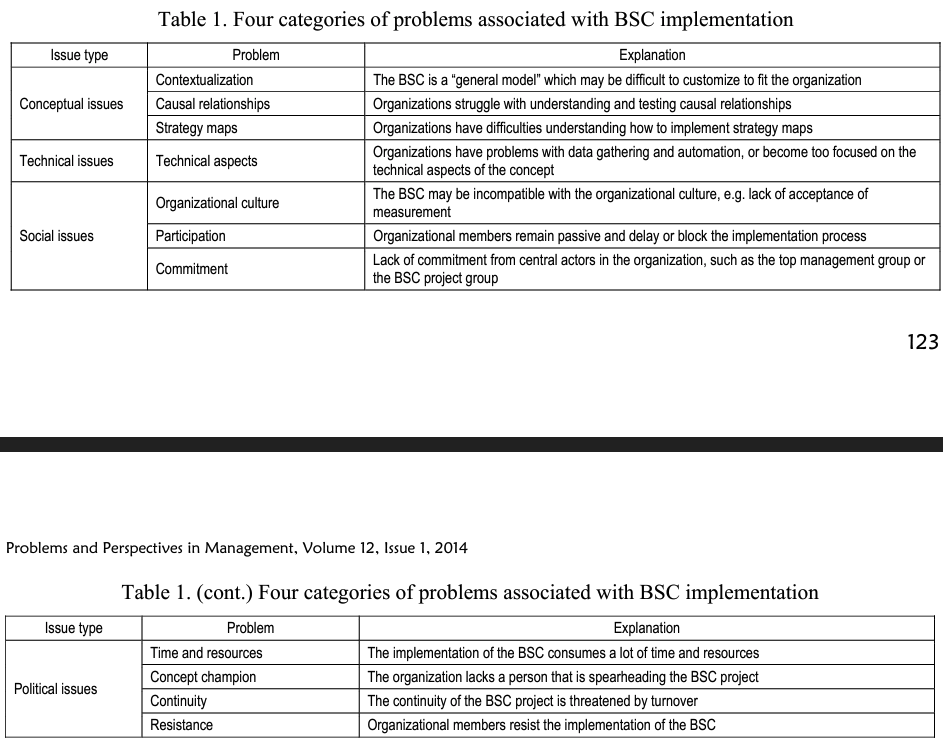

The balanced scorecard (BSC) is one of the most widely used and discussed management concepts in the world. Although many BSC success stories have been cited in the practitioner-oriented literature and in the business media, researchers have shown that the implementation of BSC can be a complicated process. There are many pitfalls and dysfunctional consequences associated with the implementation and use of the BSC. Still, little research is conducted on BSC implementation issues. This paper reports on a qualitative study of Scandinavian BSC users. Based on interview data, the paper identifies four main problem areas associated with the implementation of the BSC concept: conceptual, technical, social and political issues. These problematic issues are discussed with reference to the existing BSC literature, and more generally, the literature on the implementation of management concepts in organizations

Ключевые слова

Problems, balanced scorecard, implementation, management concepts, barriers, perceptions

Introduction

Kaplan and Norton’s ‘The Balanced Scorecard’ (e.g. Kaplan & Norton, 1992; Kaplan & Norton, 1996) is one of the most widely used and discussed management concepts in the world. The BSC has attracted lots of interest both in academic research (for recent reviews, see e.g. Banchieri, Planas & Rebull, 2011; Hoque, 2013; Lueg & e Silva, 2013; Perkins, Grey & Remmers, 2014), and among managers (e.g. Rigby & Bilodeau, 2011, 2013). Despite all the attention the BSC has received in recent years, possible implementation problems are to a large extent neglected in the research literature. As Tayler (2010, p. 1099) points out: “though scorecard proponents have begun to address scorecard implementation, little academic research has been done on balanced- scorecard implementation issues ”.

Against this background, the purpose of this paper is to explore what BSC users perceive to be the main problems associated with BSC implementation. The paper draws on qualitative data gathered by means of interviews with consultants and managers involved in BSC implementation projects in Scandinavian organizations. This research approach is suggested in previous BSC literature. Al Sawalqa, Holloway and Alam (2011, p. 206), for example, suggest that “future studies could discuss the problems and perceived benefits associated -with BSC implementation using a qualitative approach (e.g. case studies or face-to-face interviews) ”.

The paper adds to the emerging literature on BSC implementation issues (Braam, 2012; Hoque, 2013; Kasurinen, 2002; Lueg & e Silva, 2013; Modell, 2012; Norreklit, Jacobsen & Mitchell, 2008; Norreklit, Norreklit, Mitchell & Bjomenak, 2012; Oriot & Misiaszek, 2004; Tayler, 2010). It also makes an empirical contribution since organizations are generally not open about problematic issues (Francis & Holloway, 2007, p. 177). Managers may find it in their best interests to paint a glossy portrait of the organization. This is especially the case with managers recently involved in the adoption and the implementation of a new ‘fashionable’ concept since they are still in the so-called ‘honeymoon phase’.

The paper also provides practical implications for managers grappling with BSC implementation in their organizations. A better understanding of the various factors affecting the implementation and change process could help organizations to avoid potential problems (Kasurinen, 2002, p. 337). The need for a better understanding of the implementation issues is also demonstrated in the following quotation from one of the informants in this study: “Kaplan and Norton ’s concept is a good populist concept, but they [Kaplan and Norton] don’t give you any help with implementation difficulties. The concept gives you a theoretical frame of reference, but the adaptation to your organization is solely your own job ”.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. In section one we provide a review of the literature dealing with the implementation of management concepts, and more specifically the BSC. In section two follows a description of the research methodology employed in the paper. In section three we present the empirical findings, and discuss them in relation to existing research. The fourth and last section of the paper discusses the implications of the findings, both

1. The implementation of the BSC

1.1. The adoption and implementation of management concepts. Management concepts are prescriptions or recipes on how to organize certain organizational activities, i.e. business processes or reporting systems, in order to reach an organization’s long-term goals (Birkinshaw, Hamel & Mol, 2008; Braarn, Benders & Heusinkveld, 2007; Rovik, 2007). Moreover, management concepts are ideational and lack a material component (Benders & Van Bijsterveld, 2000). Hence, being ideational, management concepts are ‘interpreted’ (Benders & Van Veen, 2001), ‘translated’ (Czamiawska & Sevbn, 1996) or ‘edited’ (Sahlin-Andersson, 1996) in various ways as they are adopted as practices in organizations. As a result, the adoption and implementation of management concepts should not be seen as a discrete event isolated from its wider organizational and social context (Westphal, Gulati & Shortell, 1997). Adoption should not be treated as a dichotomous variable, i.e. as an either-or decision since organizations ‘handle’ concepts in many different ways subsequent to adoption (Rovik, 2011).

While the decision of whether or not to adopt a concept may be straightforward, the process of implementing a management concept is complex. Research on the implementation of innovations underlines that the post-adoption (i.e. implementation) phase is where most of the problems arise (Gallivan, 2001). A whole array of factors may influence the trajectory and lifecycle of a concept in an organization subsequent to its adoption. For example, studies have shown that both social and political processes play roles in the introduction and implementation of concepts and ideas in organizations (Burgelman, 1983; Burgelman & Sayles, 1986; Damanpour & Daniel Wischnevsky, 2006; Pettigrew, 1973; Wolfe, 1994). A large body of literature on organizational change has highlighted the role of ‘champions’ (e.g. Chakrabarti, 1974; Howell & Higgins, 1990) or ‘souls-of-fire’ (Stjemberg & Philips, 1993) in the implementation process, and the importance of ‘issue selling’ in order to make organizational members more receptive to change efforts and the concept itself (Dutton, Ashford, O’Neill & Lawrence, 2001).

1.2. The adoption and implementation of the BSC. The BSC is an example of a management concept which can be interpreted, enacted and implemented in various ways (Aidemark, 2001; Ax & Bjomenak, 2005; Braarn, 2012; Braarn et al., 2007; Braarn, Heusinkveld, Benders & Anbei, 2002; Braarn & Nijssen, 2004; Lueg & e Silva, 2013; Madsen & Slätten, 2013; Madsen, 2012; Modell, 2012; Norreklit, 2003). Although BSC implementation issues is an under-researched area (Tayler, 2010), there are some studies that have investigated different aspects of the BSC implementation process.

In a case study of the BSC implementation in a large Finnish company, Kasurinen (2002) identified different types of barriers to change in the BSC implementation process. For example, Kasurinen found that lack of time and resources was a potential problem, as not everyone in the organization was willing to invest sufficient time and resources on the BSC project. In another study, Andon, Baxter and Maharna (2005) showed how the BSC may upend existing performance measurement practices in an organization. This can lead to resistance from different individuals and groups in the organization. These individuals may feel that the BSC is unable to serve their interests. They may also feel threatened by the introduction of the concept. Therefore, individuals may resist the introduction of the BSC and attempt to bring the BSC project to a stand-still. Moreover, these authors identified other problems with the BSC concept such as trade-offs between the measures in the BSC, which sometimes may be in conflict.

Oriot and Misiaszek (2004) found that organizational issues played a role in the implementation of the BSC in a space technology company. BSC was found difficult to implement due to an organizational culture dominated by engineering professionals. Wickramasinghe, Gooneratne and Jayakody (2007) identified political issues related to BSC implementation, such as power games between different professional groups in the organization (e.g. engineering and finance). The authors also found that the owner-manager lacked commitment to the concept. The owner-manager was ultimately more interested in the financial indicators than the non- financial indicators. This finding is consistent with most claims in the normative BSC literature where it is assumed that top management commitment is crucial for a successful implementation.

Norreklit et al. (2008) identified several pitfalls and possible dysfunctional consequences of the BSC usage. For example, these authors found that the BSC does not sufficiently take into account the complexity of organizations as it tends to view the organizations as rational and able to plan its strategy in a top-down manner. They also found that the BSC gives little insight into the relative importance of the different measures in the BSC, and that the causal relationships between non-financial and financial measures not necessarily are valid. Thompson and Mathys (2008) identified four potentially problematic issues in the application of the BSC. First, they argue that there is often a lack of understanding of organizational processes. Second, there is a lack of understanding of alignment between different BSC elements. Third, it is often difficult to measure what the organization intends to measure. Finally, understanding how the organization’s strategy is related to the BSC can be difficult. In many ways, these authors are touching on the same issues as Norreklit et al. (2008). In another related study, Voelpel, Leibold and Eckhoff (2006) argue that the BSC can become a measurement ‘straight jacket’ which can hinder innovation and creativity.

More recently, researchers have emphasized that the BSC is implemented within an organizational and social context where various types of political and social issues may arise (Dechow, 2012; Modell, 2012). However, political and social issues have only to a limited extent been examined empirically in relation to the BSC (Modell, 2012). In a recent study, Antonsen (forthcoming) looks at how the BSC is implemented in a bank, and finds that the BSC can very easily lead to excessive control and a strong emphasis on performance measurement, which may hinder interaction and organizational learning.

Taken together, this brief literature review shows that BSC implementation is a complex process where organizations may encounter many types of problems. Despite these studies, implementation issues related to the BSC still remains an underresearched area (Tayler, 2010). Besides, a common characteristic of the extant studies is that they have predominantly employed a case study method. This has admittedly provided deep insight into the types of problems individual organizations face during the implementation phase of the BSC, but has shed less light on the extent to which these experiences are shared by other organizations. In the next section, we outline the research methodology employed to investigate what Scandinavian organizations perceive to be the main issues related to BSC implementation.

2. Research methodology

The research reported in this paper was conducted using a qualitative and explorative approach. The goal was to obtain an understanding of what users of the BSC perceive to be the problems associated with the implementation of the concept.

We conducted a total of 61 interviews in Scandinavia with both BSC organizations which were users of the concept, and BSC consultants who had experiences with implementing the concept from numerous projects in client organizations. The interviews were conducted in 2004 and 2005 as part of a larger research project on the BSC in Scandinavia (Madsen, 2011). Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions allowed for more in-depth insight than would have been possible in a traditional postal survey. The interview schedule covered several main topics. The consultants were asked about their general experiences with using the concept, both in their own client projects and as participants and observers of what was going on in their local BSC market. Many were experienced BSC-consultants and had a longitudinal overview of the BSC usage in their local market. The organizations were asked about their main experiences from the adoption and implementation of the BSC. At the time the interviews were conducted, many had worked with the BSC concept for several years and were past the ‘honeymoon period’ where they may find it hard to criticize a recently adopted concept (cf. Malmi, 2001, p. 213).

The interviews lasted between 30 and 90 minutes, and were tape-recorded and fully transcribed. An issue-focused approach (Weiss, 1994) was used to analyze the transcripts. This allowed for comparing and contrasting across informants and themes.

3. Findings

Based on the interview data, four general themes related to BSC implementation were identified: conceptual, technical, social and political issues.

3.1. Conceptual issues. A central theme that emerged from the data is what can be classified as conceptual issues. These issues concern the interpretation and understanding of the BSC concept.

3.1.1. Most of the informants tended to agree that the BSC lends itself to various interpretations. This characteristic was found useful since the concept could be modified and thereby used for different purposes (cf. Braarn, 2012; Lueg & e Silva, 2013). However, many managers appeared to struggle with the contextualization of the ‘vague’ and ‘theoretical’ BSC concept. One manager noted: ‘‘You should not underestimate the resources needed to actually tailor-make the balanced scorecard to match your company. The knowledge you get from the theory books and also from some of the cases is rather theoretical, and you need adjustments to use it in your company. ” This quote illustrates how challenging the process of contextualization can be, and that many organizations are lacking what Rovik (2001) refers to as ‘translation competence’, i.e. the knowledge or know-how to contextualize abstract and theoretical management concepts. Even a former BSC consultant admitted having problems understanding how the concept worked in practice: “I used to work with this concept as a consultant. I thought it was going to be different. I didn ’t really know how this worked in practice. So in that respect it was exciting to work with the BSC. ”

3.1.2. Causal relationships. Developing and testing causal relationships between the measures in the BSC is an essential part of Kaplan and Norton’s ‘BSC theory’. As pointed out by Hoque and James (2000, p. 3): “the use of a BSC does not mean just using more measures; it means putting a handful of strategically critical measures together in a single report, in a way that makes cause-and-effect relations transparent.” Despite the focus on causal relationships in the normative BSC literature, the informants generally admitted that little effort had been done to establish and test causal relationships in the BSC. For example, one Danish manager noted: “ When it comes to cause- and-effect relationships we have a missing link. We haven’t spent much time on that. We ought to have done that. ” Another Danish organization had done a bit more work on causal relationships, but admitted it was not a top priority: “Now and then we discuss a little bit about cause-and-effect, but it is not very much in focus, because it is so complicated. Of course we discuss it now and then when we look at the strategy map. Ok this causes that and so on. ” Similar comments were common in the interviews. “We haven’t worked much with cause-and-effect and strategy maps because it takes time. ” Many of the informants did not use, or were not even aware of these more advanced parts of the BSC concept.

The finding that few organizations are working with causal relationships is not completely surprising given previous findings in the BSC research literature. For example, Speckbacher, Bischof and Pfeiffer (2003) found that about half of the companies they investigated had not developed a causal model. Moreover, the studies of Davis and Albright (2004) and Ittner and Larcker (2003) found that an even lower percentage (about 25%) of firms developed causal models. However, the lack of causal models may be a potential problem since Othman (2006) found that organizations that had not developed a causal model experienced additional problems not faced by organizations with causal models.

3.1.3. Strategy maps. Related to causal relationships is the development of strategy maps. Strategy maps are a central part of Kaplan and Norton’s more recent books on the BSC (Kaplan & Norton, 2004, 2006, 2008). Few informants, however, had developed strategy maps, and many had not heard of this part of the BSC concept. One organization noted that “we have discussed strategy maps, but never made one ”. Moreover, several consultants commented that the use of strategy maps was rarely seen in practice. For example, one consultant noted that: “My impression is that a lot of organizations have focused very much on the original balanced scorecard model, i.e. more measurement and development of the scorecard. The focus is on the scorecard, while strategy maps etc. have been overlooked. ” Again, these observations are in line with previous findings of Speckbacher et al. (2003) who reported that less than 10% of the firms investigated used strategy maps. Instead, most firms focus on the BSC as a measurement system. As one manager said: “We haven’t worked with the strategy maps, because for us it has become more of a measurement thing. ”

The use of strategy maps may have an effect on performance. Lucianetti (2010) found that companies that used strategy maps outperformed other companies. Wilkes (2005, p. 45, cited in Lucianetti,

2010) found that in the absence of strategy maps, organizations may end up with a collection of loosely connected key performance indicators not linked to the organization’s strategy, but instead are chosen to represent the goals of different groups and individuals in the organization.

3.2. Technical issues. The second main theme that emerged from the data was issues related to the more technical aspects of the BSC, such as how to automate data gathering, but also more behavioral aspects such as the tendency to get too boggled down by a very narrow focus on technical tools (e.g. BSC software packages).

3.2.1. Technical infrastructure. One of the most common problems mentioned in the interviews was getting in place a good infrastructure that can support the BSC, e.g. automated data gathering. Many of the organizations had spent much time and resources on developing IT infrastructures to support these processes. At the same time, it was emphasized by some informants that organizations had a tendency to focus too much on technical aspects of the BSC: ‘‘I think the novices -with regards to balanced scorecard -will typically use tremendous amounts of resources on IT infrastructure. Typically 75% of the resources on IT infrastructure and only 25% on the content of the balanced scorecard. In my opinion it should be 10% IT and 90% should be focused on getting meaningful links between the KPIs and your strategy. ”

3.2.2. Most of the organizations used some kind of software tool to support their work with the BSC. Some organizations had developed their own Excel-based software application while others had purchased a BSC software package from one of the many software vendors in the BSC market. Several consultants noted that use of these software tools may lead to certain types of dysfunctional behavior since organizations may focus too much on the technical aspects of the concept, while ignoring the conceptual issues, e.g. modifying the concept to fit then- organizations. Consider this quote from Norwegian user of the concept: “I think a lot of organizations have focused too much on the tool. They have measured and measured without really focusing on what they have been measuring. The measures have not at all been linked to strategy, and then they are meaningless. If you let loose a bunch of accountants, and let them play with a scorecard, they can do a lot of harm. A lot of organizations have moved straight to measurement, and viewed this as a project within the accounting department, measuring bits, pieces and millimetres without giving any arguments as to how it is linked to the strategy. ”

A consultant commented on the tendency for managers to rely too much on software tools: “There are these people who come home from these conferences where they have seen these red, yellow and green lights, and would love to have these computer screens where they can sit and run their business. If the light is green, they can go home and relax. ’’

3.2.3. Too much focus on measurement. The interview data suggest that the use of BSC software has a tendency to lead to a stronger focus on measurement at the expense of developing the concept in the organization. It was mentioned in the interviews that this problem can be exacerbated if the concept is owned by the accounting/finance department. Accounting/finance people tend to interpret the BSC as an technical measurement tool (cf. Braarn et al., 2002), and have less focus on organizational and strategic issues. Several of the consultants commented on the tendency for organizations to be very focused on measurement. For example, one consultant noted: “A lot of organizations just brainstorm and find a lot of indicators that they measure, but have no process around it. The goal is to find some indicators along several dimensions and measure those. ” Similarly, another consultant pointed out that “a lot of organizations say that ‘this is a strategic tool’. They call it a strategic tool, but they use it just for reporting, and it has nothing to do with strategy. ”

3.3. Social issues. A third theme was social issues related to the implementation of the BSC, including incompatible organizational culture, lack of participation, and a lack of commitment.

3.3.1. Organizational culture. First, the BSC may be incompatible with the culture in the organization. For example, one Danish informant explained how his organization has always been dominated by financial numbers and control: “We have met some organizational resistance when implementing the concept. Our organization has always been dominated by numbers. ” This organization resisted the implementation of a multi-dimensional measurement system since it upended existing power structures in the organization by focusing on other aspects than just the traditional financial numbers. In this case, power shifted from the accounting and finance department to other parts of the organization. Another project manager stated that his organization resisted the BSC because it was not ‘culturally and intellectually ready’ for the introduction of the BSC: “At the time when we started, the organization wasn’t ready. (...) it has something to do with the cultural and in some ways the intellectual level of our organization. ”

3.3.2. Organizational members may remain passive and slow down the implementation process. One Danish organization pointed out that ‘‘some members of the organization thought this was very academic and theoretically difficult to understand. They didn’t understand that the system we used to have just wasn ’t good enough. They felt that we intervened in their daily activities, and that we in the accounting department implemented this for our own sake and not to help them. ” In this case, the project leaders had not succeeded in selling the BSC concept to the organization (cf. Dutton et al., 2001).

3.3.3 Commitment. Lack of commitment from central actors in the organization, such as the top management group or the project group can be a serious problem in BSC projects. Consider this quote from a project manager: “It is important to have 100% commitment from the top managers. If not, you can forget it. It is extremely important”. The level of commitment also has a tendency to vary over time, as a result of organizational events such as turnover in the top management team. Such disruptions may affect the BSC project negatively, as noted by one informant: “The top management had ownership to the process, but the project died when we were in the implementation phase. We got a new CEO who wasn’t as interested in the balanced scorecard. That was in the end of 2002. In 2003 when we going to implement all over again, there was no commitment from the top management group. The CEO wasn’t interested. Then we got a new CEO - again. He had worked with Business Performance Measurement in his earlier job, and would really like a tool such as Balanced Scorecard”.

Another project manager pointed out that the rest of the organization showed very tittle interest in the BSC project: “Since we started one year ago, only one person has asked how the project is going. Only one of the top managers! People don’t feel that they need this in their daily work”. Lack of commitment means that the BSC becomes ‘stowed away’ somewhere in the organization, and that the project manager becomes marginalized. The interviews also revealed that lack of commitment can be crucial for the survival of the concept in the organization. This manager shared his experiences from talking to BSC users in other organizations: “Getting the management’s backing and focus on the implementation of the Balanced Scorecard is a common problem. I have plenty of examples here. I have many colleagues who have had difficulties in their organizations getting acceptance and support from top management to run such a process. And then it dies. ”

Lack of commitment is the result of the BSC not being a ‘company-wide’ project. Instead, the concept is only driven by the project group, and top managers are not participating or giving the work much thought. A project manager noted: “Commitment is our biggest problem. We’re talking at the top level. It’s not good, and we’re not proud of it. The reason might be that they have somebody like me who does much of the work. So they don’t have to do anything. So when I have updated the numbers and people have given me input, and I present the scorecardfor about an hour. The reaction is often “fine, let’s move on”. And it’s not looked at until next time. Unless we come up with some initiatives and specific actions, then they might have to do something. ”

3.4. Political issues. The final theme that emerged from the data is related to political issues in BSC implementation. The most frequently mentioned issues were insufficient time and resources, the lack of concept champion, lack of continuity and resistance from different parts of the organization.

3.4.1. Time and resources. Papalexandris, loannou and Prastacos (2004) found that the need of time and resources during the implementation process may cause implementation costs to outweigh the benefits from using the concept. Several of the informants noted that the use of the BSC consumes a lot of time and resources. One manager noted that the BSC “takes time to get under people’s skin”. Another manager noted how “it takes time for the organization to understand and use a concept or method like the BSC. It is not something you do overnight. ” Time and resources can also be related to a lack of commitment from top managers who are unwilling to make the BSC project enough of a priority in the organization. One informant explained: “I know many examples where the top management has agreed to go forward with a balanced scorecard process, but not been willing to invest the time, resources and patience needed to succeed. ”

3.4.2. Concept champion. Quite often organizations lack a person who is spearheading the BSC project. One consultant noted that “In some cases consultants have hyped up this concept, and written nice reports, done some minor things, but when the consultant leaves the organization, the wheels come of the balanced scorecard wagon. ” In other words, the organization lacked a ‘champion’ (Chakrabarti, 1974) or ‘soul-of-fire’ (Stjemberg & Philips, 1993) who could sustain the work on the BSC concept after the consultants had left the organization.

3.4.3. The interviews indicate that many organizations struggle to keep the ‘BSC flame’ burning. For example, one project managers pointed out how this can be difficult in organizations with high turnover and many new hires: “The difficult

part is that everybody should be engaged and in the meantime we have a few new members and they have not been part of the process since the beginning, so they haven’t got the same feelings about the system. ”

The BSC process is affected by external factors such as economic decline. Organizations and managers stated that they tend to revert back to old habits and ways of doing things during downturns. One manager pointed out how the concept had gone through phases in terms of the level of interest: “Our journey from 1996 onwards has had ups and downs with respect to focus and interest. ”

The continuity of the BSC project is also often threatened by personnel turnover. Many informants pointed out the lack of continuity as a potential problem in the implementation phase, particularly, in times of economic decline. As one manager of a large Danish company pointed out: “1.5 years ago our CEO restructured the top management group and said that ‘now we have a period where we are going to focus on making money and retaining our customers’. In this period we haven’t had much emphasis on balanced scorecard in our top management group. (...) But things are better now. After a turnaround, we now have strength too start looking at the softer stuff again. (...) It ’s an important question in relation to balanced scorecard, what you do when you have a crisis. Do you keep using the balanced scorecard or do you go back to the traditional systems that you know? Everybody can understand the soft stuff when things are going well, but when you are struggling this changes. People go for the sure thing, what will deliver results in the short run. ”

Another factor that appears to have a negative impact on the continuity is the turnover among the top managers. As one project manager lamented: “Our tragedy was that we had turnover in the top management group. If that had not been the case, I think we would have come a lot further. ”

3.4.4. There are potential pitfalls related to the use of words and labels that are recognized as being ‘fashionable’ in the business community. Particularly if an organization has experienced failure when introducing other concepts, this can lead to resistance against new concepts and ideas. As Rovik (2011) puts it, the organization acquires ‘immunity’ to fashionable ideas. One consultant described his experiences from past implementation projects in organizations where the employees had a history of failed implementations of management concepts. He pointed out that “in Scandinavia people have their own opinions, and people are cynical in the sense that if the manager is tricking them every year with “new concepts ” and see that nothing really happens, then why should they bother? It is like giving candy to children and then taking it away”.

The resistance may be directed towards the label ‘BSC’ which for some may be ‘toxic’ if they have experiences other failed implementations of fashionable concepts in the past (cf. Benders & Van Veen, 2001). The resistance may also be a more general skepticism towards change initiatives if the new management concept is not compatible with the cultural values of the organization. For example, one manager noted that “we have met some organizational resistance when implementing the concept. Our organization has always been dominated by numbers. It is very difficult to introduce to some of the regional offices that the financial results are a result of our customer, process and employee results. ”

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical implications. The data show that organizations perceive a wide range of problems related to BSC implementation, spanning from conceptual/technical to social/political problems. In several cases, these problems appear to be interrelated. Organizations that struggle with conceptual or technical issues appear more likely to experience social and political problems related to the BSC. For example, organizations that struggle with conceptual issues related to causal relationships and strategy maps may just use the BSC as ‘measurement instrument’ and not attempt to use it as a strategic management system. Studies suggest that many of the benefits of the BSC are derived from the process where organizations use the BSC as a way of complementing their strategy process (Braarn & Nijssen, 2004; Davis & Albright, 2004; De Geuser, Mooraj, & Oyon, 2009), e.g. by using strategy maps (Lucianetti, 2010). In addition, an overemphasis on technical tools such as software packages and ‘cockpits’ may lead some managers to lose sight of the social and political context in which the BSC is implemented.

More generally, the findings can be discussed in light of the literature on the implementation of management concepts. The data show that organizations ‘handle’ management concepts in various ways in the post-adoption phase (cf. Rovik, 2011). In addition, the abstractness and vagueness of the concepts open up a range of implementation problems, as organizations struggle with contextualizing and ‘translating’ the concept to fit their specific organizational structure, culture and strategies.

4.2. Practical implications. Based on the interview data and the existing research on BSC implementation reviewed in this paper, several key success factors for practitioners can be identified. First, it is important to not underestimate the time and resources needed to implement a full-fledged BSC. Second, it is important to have the commitment and support of the top management to ensure that the BSC receives the necessary level of attention and sufficient time and resources. Third, it is vital to have a ‘BSC general’ in charge of the project that can keep the ‘flame burning’ even when the organization experiences difficult economic times, or experiences turnover among key personnel involved in the project. Finally, possible implementation problems appear to be related to how an organization interprets and applies the BSC.

Conclusions

Summary. Based on the interview data, four categories of potential implementation problems were identified: conceptual, technical, social and political issues. First, the conceptual issues are related to understanding the more complex part of the BSC concept, like cause-and-effect relationships and the development of strategy maps, and how to modify and adapt the standard BSC model to fit the organization. Second, technical issues are related to technical infrastructure, software and too much focus on measurement. Third, social issues are related to incompatibility between the BSC and the organizational culture, lack of participation by key members of the organization, and lack of commitment from the top management. Finally, political issues are related to underestimation of time and resources required to implement the concept, lack of a concept champion, difficulties in keeping continuity during bad times, and different types of organizational resistance to the concept.

Limitations. The research carried out in this paper is explorative in nature, and has several limitations. First, the exposure to each organization was limited and only one interview was conducted within each organization. Typically the interviewee was a BSC project leader. Hence, it is not possible to know whether these perceived problems are the actual problems experienced by the rest of the organization.

Furthermore, the research has relied on informants’ recollections of past events, which may result in biases and distortions, such as post hoc rationalization. For example, it is possible that the informants downplayed negative experiences. As pointed out by Mahni (2001, p. 213), informants may find it difficult to be critical of something they have just started using. However, most of the organizations that participated in this study had at least a couple of years of experience with the BSC, and most seemed honest about what they thought were the potential problems related to the BSC. Since informants have a tendency to report what reflects positively on them (Cook, Campbell & Day, 1979), the fact that they were willing to share negative experiences is an indication that they gave a relatively fair representation of their experiences.

Finally, the research design is not able to link the interpretations and design of the BSC in the organization to what types of problems are experienced. Researchers have pointed out that whether or not a BSC project is successful, depends to a large extent on how the BSC is interpreted, implemented and used (Braarn & Nijssen, 2004, p. 335). It is conceivable that organizations imple-menting a well- fitted version of the BSC, will be more successful (Braarn & Nijssen, 2004; Davis & Albright, 2004; De Geuser et al., 2009) and will perceive fewer problems in the implementation phase.

Future research. The findings in this paper are tentative and should be investigated more in-depth in future studies. Researchers should make use of more advanced methodological designs, such as case studies drawing on various types of micro-data, direct observations of the BSC usage and interviews of multiple informants at different levels of the organization. This echoes recent calls for more research on the politics of the BSC at different levels of the organization (Modell, 2012). Future studies should also be conducted longitudinally, as different types of implementation problems are likely to be experienced at different points in time in the implementation process of a concept.

Future studies could also attempt to design multiple case studies to compare how the BSC is implemented in organizations that interpret, design and use the BSC in different ways. For example, it would be interesting to study how the implementation process unfolds in organizations that use the concept either as a ‘performance measurement system’ or as a ‘strategic management system’ (Braarn & Nijssen, 2004; Speckbacher et al., 2003). Such research could provide useful insights into the main pitfalls and problems companies encounter in different types of BSC usage. This would be very valuable for managers struggling to implement the BSC or other types of management concepts.

References

- Aidemark, L.G. (2001). The Meaning of Balanced Scorecards in the Health Care Organization, Financial Accountability & Management, 17 (1), pp. 23-40.

- Al Sawalqa, F., Holloway, D. & Alam, M. (2011). Balanced Scorecard implementation in Jordan: An initial analysis, International Journal of Electronic Business Management, 9 (3), pp. 196-210.

- Andon, ?., Baxter, J. & Mahama, H. (2005). The Balanced Scorecard: Slogans, Seduction and State of Play, Australian Accounting Review, 15 (1), pp. 29-38.

- Antonsen, Y. (forthcoming). The downside of the Balanced Scorecard: A case study from Norway, Scandinavian Journal of Management.

- Ax, C. & Bjorn enak, T. (2005). Bundling and diffusion of management accounting innovations - the case of the balanced scorecard in Sweden, Management Accounting Research, 16, pp. 1-20.

- Banchieri, L.C., Planas, F.C. & Rebull, M.V.S. (2011). What has been said, and what remains to be said, about the balanced scorecard? Proceedings of Rijeka Faculty of Economics - Journal of Economics and Business, 29 (1), pp. 155-192.

- Benders, J. & Van Bijsterveld, M. (2000). Leaning on lean: The reception of management fashion in Germany, New Technology, Work and Employment, 15, pp. 50-64.

- Benders, J. & Van Veen, K. (2001). What’s in a fashion? Interpretive viability and management fashions, Organization, 8 (1), pp. 33-53.

- Birkinshaw, J., Hamel, G. & Mol, M.J. (2008). Management innovation, Academy of Management Review, 33 (4), pp. 825-845.

- Braam, G. (2012). Balanced Scorecard’s Interpretative Variability and Organizational Change. In C.-H. Quah & O. L. Dar (eds.), Business Dynamics in the 21st Century:

- Braam, G., Benders, J. & Heusinkveld, S. (2007). The balanced scorecard in the Netherlands: An analysis of its evolution using print-media indicators, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 20 (6), pp. 866-879.

- Braam, G., Heusinkveld, S., Benders, J. & Aubel, A. (2002). The reception pattern of the balanced scorecard: Accounting for interpretative viability, SOM-Theme G: Cross-contextual comparison of institutions and organisations, Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Nijmegen School of Management, University of Nijmegen.

- Braam, G. & Nijssen, E. (2004). Performance effects of using the Balanced Scorecard: a note on the Dutch experience, Long Range Planning, 37, pp. 335-349.

- Burgelman, R.A. (1983). A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in the Diversified Major Firm, Administrative Science Quarterly, 28 (2), pp. 223-244.

- Burgelman, R.A. & Sayles, L.R. (1986). Inside corporate innovation : strategy, structure, and managerial skills, New York Free Press.

- Chakrabarti, A.K. (1974). Role of Champions in Product Innovation, California Management Review, 17 (2).

- Cook, T.D., Campbell, D.T. & Day, A. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: design & analysis issues for field settings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Czamiawska, B. & Sevön, G. (1996). Translating organizational change, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Damanpour, F. & Daniel Wischnevsky, J. (2006). Research on innovation in organizations: Distinguishing innovation-generating from innovation-adopting organizations, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 23 (4), pp. 269-291.

- Davis, S. & Albright, T. (2004). An investigation of the effect of Balanced Scorecard implementation on financial performance, Management Accounting Research, 15 (2), pp. 135-153.

- De Geuser, F., Mooraj, S. & Oyon, D. (2009). Does the Balanced Scorecard Add Value? Empirical Evidence on its Effect on Performance, European Accounting Review, 18 (1), pp. 93-122.

- Dechow, N. (2012). The Balanced Scorecard-Subjects, Concept and Objects - A Commentary, Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 8 (4), pp. 511-527.

- Dutton, J.E., Ashford, S.J., O’Neill, R.M. & Lawrence, K.A. (2001). Moves That Matter: Issue Selling and Organizational Change, Academy of Management Journal, 44 (4), pp. 716-736.

- Francis, G. & Holloway, J. (2007). What have we learned? Themes from the literature on best-practice benchmarking, International Journal of Management Reviews, 9 (3), pp. 171-189.

- Gallivan, M.J. (2001). Organisational Adoption and Assimilation of Complex Technological Innovations: Development and Application of a New Framework, The Database for Advances in Information Systems, 32 (3), pp. 51-85.

- Hoque, Z. (2013). 20 years of studies on the Balanced Scorecard: Trends, accomplishments, gaps and opportunities for future research, The British Accounting Review,

- Hoque, Z. & James, W. (2000). Linking Balanced Scorecard measures to size and market factors: impact on organizational performance, Journal of Management Accounting Research, 12,pp. 1-17.

- Howell, J.M. & Higgins, C.A. (1990). Champions of technological innovation, Administrative Science Quarterly, 35 (2), pp. 317-341.

- Ittner, C D. & Larcker, D.F. (2003). Coming up short on nonfinancial performance measurement, Harvard Business Review, 81(11), pp. 88-95.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1992). The balanced scorecard - Measures that drive performance, Harvard Business Review (January-February), pp. 71-79.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (2004). Strategy Maps: Converting intangible assets into tangible outcomes, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (2006). Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Synergies, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (2008). Execution Premium: Linking Strategy to Operations for Competitive Advantage, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kasurinen, T. (2002). Exploring management accounting change: The case of balanced scorecard implementation, Management Accounting Research (September), pp. 323-343.

- Lucianetti, L. (2010). The impact of the strategy maps on balanced scorecard performance, International Journal of Business Performance Management, 12 (1), pp. 21-36.

- Lueg, R. & e Silva, A.L.C. (2013). When one size does not fit all: a literature review on the modifications of the balanced scorecard, Problems and Perspectives in Management, 11 (3), pp. 86-94.

- Madsen, D. & Slatten, K. (2013). The Role of the Management Fashion Arena in the Cross-National Diffusion of Management Concepts: The Case of the Balanced Scorecard in the Scandinavian Countries, Administrative Sciences, 3 (3), pp. 110-142.

- Madsen, D.0. (2011). The impact of the balanced scorecard in the Scandinavian countries: a comparative study of three national management fashion markets, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian School of Economics, Department of Strategy and Management, Bergen, Norway.

- Madsen, D.0. (2012). The Balanced Scorecard i Norge: En Studie av konseptets utviklingsforlop fra 1992 til 2011, Praktisk okonomi ogfmans, 4, pp. 55-66.

- Malmi, T. (2001). Balanced scorecards in Finnish companies: A research note, Management Accounting Research, 12, pp. 207-220.

- Modell, S. (2012). The Politics of the Balanced Scorecard, Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 8 (4), pp. 475-489.

- Norreklit, H. (2003). The balanced scorecard: What is the score? A rhetorical analysis of the balanced scorecard, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28 (6), pp. 591-619.

- Norreklit, H., Jacobsen, M. & Mitchell, F. (2008). Pitfalls in using the balanced scorecard, Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 19, pp. 65-68.

- Nerreklit, H., Norreklit, L., Mitchell, F. & Bjornenak, T. (2012). The rise of the balanced scorecard! Relevance regained? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 8 (4), pp. 490-510.

- Oriot, F. & Misiaszek, E. (2004). Technical and organizational barriers hindering the implementation of a balanced scorecard: the case of a European space company. In M.J. Epstein, & J.F. Manzoni (eds.), Studies in Managerial and Financial Accounting, 14, pp. 265-301. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Othman, R. (2006). Balanced scorecard and causal model development: preliminary findings, Management Decision, 44 (5), pp. 690-702.

- Papalexandris, A., loannou, G. & Prastacos, G.P. (2004). Implementing the balanced scorecard in Greece: a Software Firm’s Experience, Long Range Planning, 37 (4), pp. 351-366.

- Perkins, M., Grey, A. & Remmers, H. (2014). What do we really mean by “Balanced Scorecard?” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63 (2), pp. 148-169.

- Pettigrew, A.M. (1973). The Politics of Organizational Decision-Making, London: Tavistock.

- Rigby, D. & Bilodeau, B. (2011). Management Tools & Trends 2011, London: Bain & Company.

- Rigby, D. & Bilodeau, B. (2013). Management Tools & Trends 2013, London: Bain & Company.

- Ravik, K.A. (2001). Overforing og oversettelse av ledelsesteknologier i den globale organisasjonslandsby. In S. Jönsson & B. Larsen (eds.), Teori & Praksis - Skandinaviske perspektiver pa ledelse og okonomistyring. Kobenhavn: Jurist- og 0konomforbundets Forlag.

- Ravik, K.A. (2007). Trender og translasjoner - ideer som former det 21. arhundrets organisasjon. Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget.

- Ravik, K.A. (2011). From Fashion to Virus: An Alternative Theory of Organizations’ Handling of Management Ideas, Organization Studies, 32 (5), pp. 631-653.

- Sahlin-Andersson, K. (1996). The construction of organizational fields. In B. Czamiawska, & G. Sevön (eds.), Translating organizational change, 69-92. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Speckbacher, G., Bischof, J. & Pfeiffer, T. (2003). A descriptive analysis of the implementation of balanced scorecards in German-speaking countries, Management Accounting Research (December), pp. 361-388.

- Stjemberg, T. & Philips, A. (1993). Organizational innovations in a long-term perspective: Legitimacy and souls- of-fire as critical factors of change and viability, Human Relations, 46, pp. 1193-1219.

- Tayler, W.B. (2010). The Balanced Scorecard as a Strategy-Evaluation Tool: The Effects of Implementation Involvement and a Causal-Chain Focus, The Accounting Review, 85 (3), pp. 1095-1117.

- Thompson, K. & Mathys, N. (2008). An improved tool for building high performance organizations, Organizational Dynamics, 37 (4), pp. 378-393.

- Voelpel, S.C., Leibold, M. & Eckhoff, R.A. (2006). The tyranny of the Balanced Scorecard in the innovation economy, Journal of Intellectual Capital, 7 (1), pp. 43-60.

- Weiss, R.S. (1994). Learning from strangers: The art and method of qualitative interview studies, New York: Free Press.

- Westphal, J.D., Gulati, R. & Shortell, R.S. (1997). Customization or conformity? An institutional and network perspective on the content and consequences of TQM adoption, Administrative Science Quarterly, 42 (2), pp. 366-394.

- Wickramasinghe, D., Gooneratne, T. & Jayakody, J. (2007). Interest lost: the rise and fall of a balanced scorecard project in Sri Lanka, Advances in Public Interest Accounting, 13, pp. 237-271.

- Wilkes, J. (2005). Leading and lagging practices in performance management, Measuring Business Excellence, 9 (3).

- Wolfe, R.A. (1994). Organizational Innovation: Review, Critique and Suggested Research Directions, Journal of Management Studies, 31 (3), pp. 405-431.