Summertime plankton ecology in Fram Strait - a compilation of long- and short-term observations

Опубликована Дек. 1, 2015

Последнее обновление статьи Авг. 15, 2023

Abstract

Between Greenland and Spitsbergen, Fram Strait is a region where cold ice-covered Polar Water exits the Arctic Ocean with the East Greenland Current (EGC) and warm Atlantic Water enters the Arctic Ocean with the West Spitsbergen Current (WSC). In this compilation, we present two different data sets from plankton ecological observations in Fram Strait: (1) long-term measurements of satellite-derived (1998–2012) and in situ chlorophyll a (chl a) measurements (mainly summer cruises, 1991–2012) plus protist compositions (a station in WSC, eight summer cruises, 1998–2011); and (2) short-term measurements of a multidisciplinary approach that includes traditional plankton investigations, remote sensing, zooplankton, microbiological and molecular studies, and biogeochemical analyses carried out during two expeditions in June/July in the years 2010 and 2011. Both summer satellite-derived and in situ chl a concentrations showed slight trends towards higher values in the WSC since 1998 and 1991, respectively. In contrast, no trends were visible in the EGC. The protist composition in the WSC showed differences for the summer months: a dominance of diatoms was replaced by a dominance of Phaeocystis pouchetii and other small pico- and nanoplankton species. The observed differences in eastern Fram Strait were partially due to a warm anomaly in the WSC. Although changes associated with warmer water temperatures were observed, further long-term investigations are needed to distinguish between natural variability and climate change in Fram Strait. Results of two summer studies in 2010 and 2011 revealed the variability in plankton ecology in Fram Strait.

Ключевые слова

Climate change, Fram Strait, biogeochemistry, Arctic Ocean, Plankton, ecology

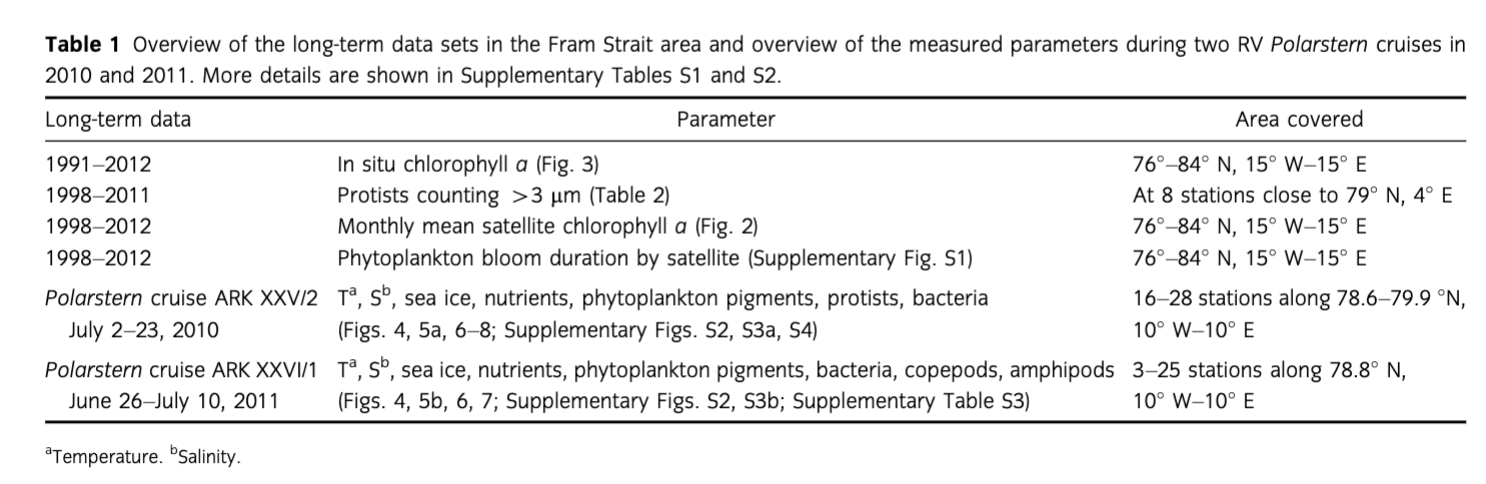

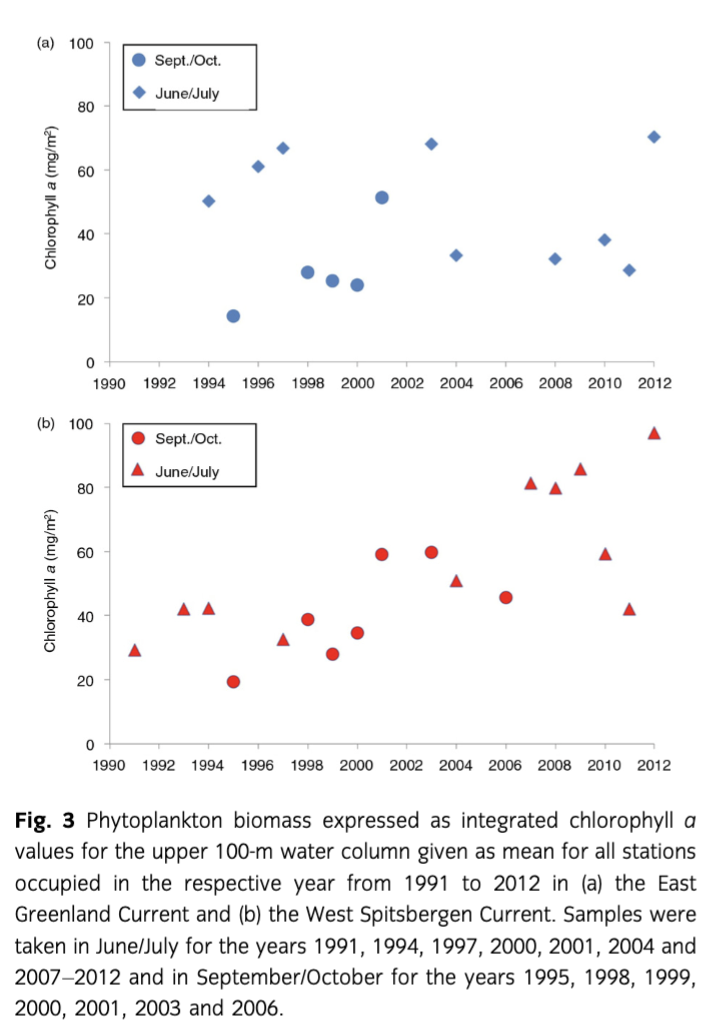

Fram Strait, located in the transition zone between the northern North Atlantic and the central Arctic Ocean, is a deep gateway where two hydrographic regimes partly converge (Fig. 1). In eastern Fram Strait, the West Spitsbergen Current (WSC) transports warm (2.7°C–8°C) Atlantic Water (AW) into the Arctic Ocean, while the East Greenland Current (EGC) carries cold (ca. −1.7°C–0°C) Polar Water (PW) in the upper 150 m towards the south in the western part of the strait.

Recently, a warming of AW entering the Arctic Ocean with the WSC was recorded in eastern Fram Strait, with an increase of the mean temperature of 0.068°C yr−1 from 1997 to 2010 (Beszczynska-Möller et al. 2012). In addition to this long-term trend, a warm anomaly event was also observed in eastern Fram Strait during the past decade. The warmer period began in late 2004, reached a peak in September 2006 and persisted until a significant decrease in temperature was recorded in 2008 (Beszczynska-Möller et al. 2012). This period of increased water temperature was defined as the warm anomaly of 2005–07, when temperature anomalies exceeding 1°C were observed in eastern Fram Strait (Beszczynska-Möller et al. 2012).

In addition to warmer temperatures, the eastern part of Fram Strait is generally characterized as a region of low ice cover and is intermittently affected by ice drifting out of the Arctic Ocean. In contrast, the western part of Fram Strait is ice-covered for most of the year and exhibits high variability in sea-ice extent depending largely on ice transported with the Transpolar Drift. Higher southward ice drift velocities caused by stronger geostrophic winds increased the volume of ice exported through Fram Strait from 2005 to 2008 (Smedsrud et al. 2008; Smedsrud et al. 2011). In the central Arctic Ocean, an accelerated decrease in sea-ice extent and thickness has recently been observed (e.g., Symon et al. 2005; Maslanik et al. 2007; Solomon et al. 2007; Comiso et al. 2008; Maslanik et al. 2011; Comiso 2012). The thinning of sea ice in the central Arctic Ocean could be one reason for an increasing ice transport south through Fram Strait.

Despite its dynamic hydrography, Fram Strait is well suited for studies of the impact of changes in ice cover and water temperature on planktonic variability on account of its relatively good accessibility. During the past decades, Fram Strait has been the investigation area of several studies, though detailed and continuous studies of the pelagic ecosystems are rare, particularly in the western part. Exceptions consist of the large interdisciplinary study Marginal Ice Zone Experiment in the mid-1980s (e.g., Smith et al. 1987; Gradinger & Baumann 1991; Hirche et al. 1991) and the Northeast Water polynya project as part of the International Arctic Polynya Programme in the 1990s (e.g., Bauerfeind et al. 1997).

More recently, a comprehensive characterization of the physical and biological properties of the pelagic system indicated an average primary production of ca. 80 g C m−2 yr−1 for the entire Fram Strait (Hop et al. 2006). Results from another assessments made by Wassmann et al. (2010) using a three-dimensional SINMOD model for the period from 1995 to 2007 in Fram Strait identified three zones of annual primary productivity: AW, where annual primary production estimates ranged between 100 and 150 g C m−2 yr−1; partly ice-covered cold waters, where annual productivity is lower and ranged between 50 and 100 g C m−2 yr−1; and permanently ice-covered regions, where annual primary production values are <50 g C m−2 yr−1. The lowest variability of gross primary production in the model was found in the Atlantic-influenced domain that did not change significantly from 1995 to 2007 (Wassmann et al. 2010; Wassmann 2011). Reigstad et al. (2011) described in another model approach a slight increase in primary production in the WSC from 2001 to 2004 probably due to reduced sea-ice cover. Forest et al. (2010) predicted a pelagic system with increasing retention, decreasing productivity and decreasing vertical particle flux should the warming trend continue in the WSC. Lalande et al. (2013) showed that the warm anomaly event from 2005 to 2007 in eastern Fram Strait also had an impact on the composition of particles in sedimenting matter; export of biogenic matter shifted from large diatoms towards smaller cells. The recent investigations reveal possible differences in productivity for the WSC and EGC as well as indicate changes of physics and biology. However, more and longer long-term field observations are essential to ground truth predictions of change in regional ecosystems.

In this overview, we present long-term data of satellite-derived chlorophyll a (chl a; 1998–2012, 15 years) and in situ chl a measurements (1991–2012, 22 years with 19 summer, one spring and two fall cruises). Data for both were obtained for the area between 76° N and 84° N and 15° W and 15° E in Fram Strait (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). We also show long-term data of unicellular plankton species (1998–2011, eight summer cruises) obtained at one permanent station situated in the long-term observatory Hausgarten (ca. 79° N, 4° E; Supplementary Table S1).

Finally, we present an integrated data set consisting of physical, biogeochemical and biological parameters (including traditional plankton investigations, remote sensing, zooplankton, microbiological and molecular studies, and biogeochemical analyses) measured at Hausgarten and along an oceanographic transect across Fram Strait at ca. 78° 50′ N during summer 2010 and 2011 (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S2). This work supplements information on pelagic communities and biogeochemistry to the deep-sea monitoring programme at Hausgarten, a long-term deep-sea observatory established by the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research.

Material and methods

Long-term measurements

To facilitate the interpretation of satellite and field measurements, the prime meridian was selected to separate the EGC and the WSC. A lack of satellite data in the ice-covered EGC region prevented a differentiation into three zones as was done in the following section on the summer cruises of 2010 and 2011. The mixed water (MW) zone we introduce in the next section is therefore not distinctively considered in the long-term study.

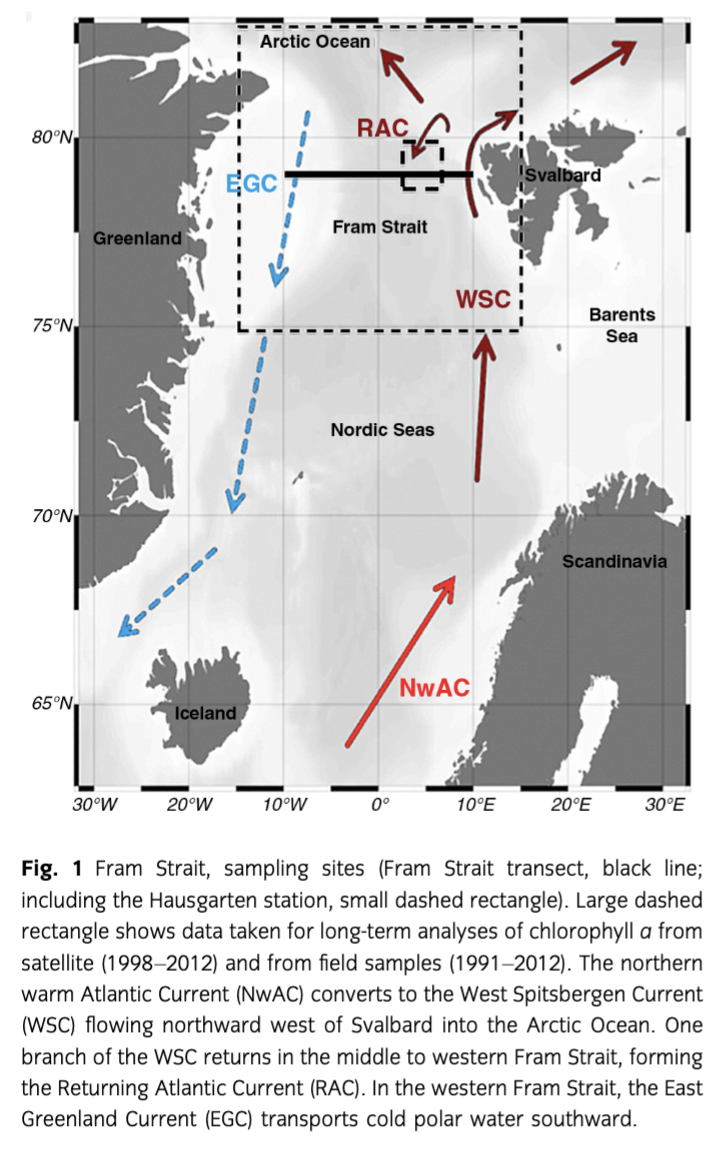

Satellite-derived chl a

Satellite chl a level-3 data for open ocean (case-1 waters) were taken from the GlobColour archive (www.hermes.acri.fr). This product of 4.6-km spatial resolution is based on the merging of level-2 data from three ocean colour sensors: Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS), Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and Sea-Viewing Wide Field-of-View Sensor (SeaWiFS) using an algorithm developed by Maritorena & Siegel (2005). The spatially averaged monthly chl a concentrations were studied for the region from April 1998 to August 2012 (Fig. 2, Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). The variability and trend of phytoplankton biomass in the regions west and east of the prime meridian were determined considering the monthly mean values. In addition, the timing and duration of the phytoplankton blooms was calculated (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In situ chl a and protistian plankton composition

In situ chl a concentrations were determined mainly during summer from 1991 to 2012 (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). Seawater (0.5–2.0 L, from 8 to 12 depths from surface to 100 m) collected with a conductivity–temperature–depth (CTD) rosette seawater sampling system equipped with 24 Niskin bottles was filtered onto 25-mm diameter GF/F filters (Whatman, Kent, UK) for chl a measurements. Filters were stored deep-frozen below −18°C and −25°C until they were extracted (ca. three months after the cruise) in 90% acetone and analysed with a spectrophotometer for higher values and/or a fluorometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) for lower values slightly modified to the methods described in Edler (1979) and Evans et al. (1987), respectively. (For more details, see the Supplementary File.)

In order to study the species composition of unicellular plankton organisms, water samples were collected from distinctive depths between the surface and 50 m at one single station: the central station at Hausgarten during eight summer expeditions between 1998 and 2011 (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). Samples were collected in July or August, except in 1998, when samples were collected in early September. Cell abundances presented here were counted at the chl a maximum of the respective station. In the laboratory, quantitative microscopic analysis of phytoplankton and protozooplankton was conducted according to Utermöhl (1958) using 50 mL aliquots. (For more details, see the Supplementary File.)

Multidisciplinary studies, summer 2010 and 2011

Sampling times and parameters analysed are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2. Molecular biological studies are only shown for 2010, zooplankton sampling started in 2011.

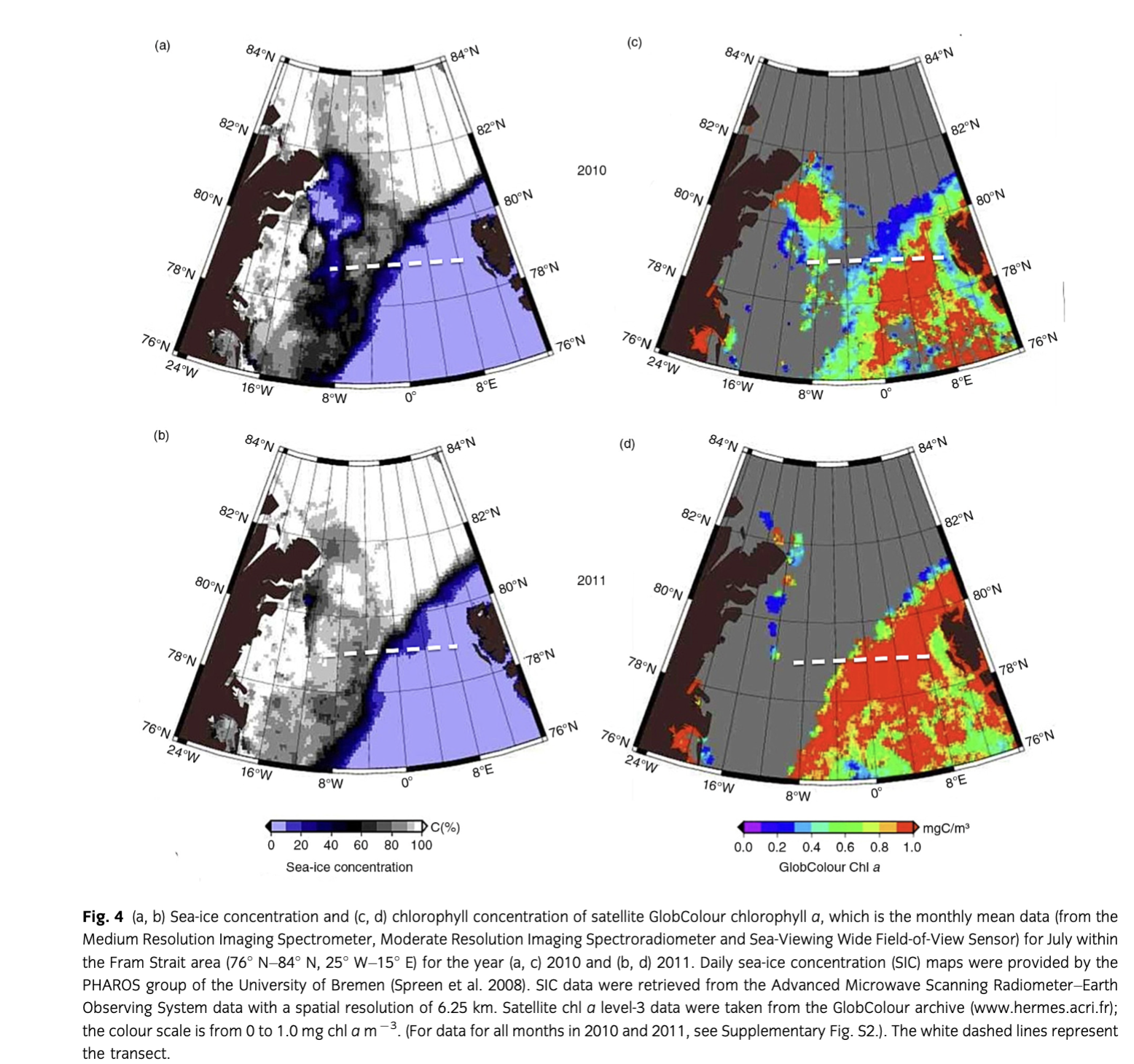

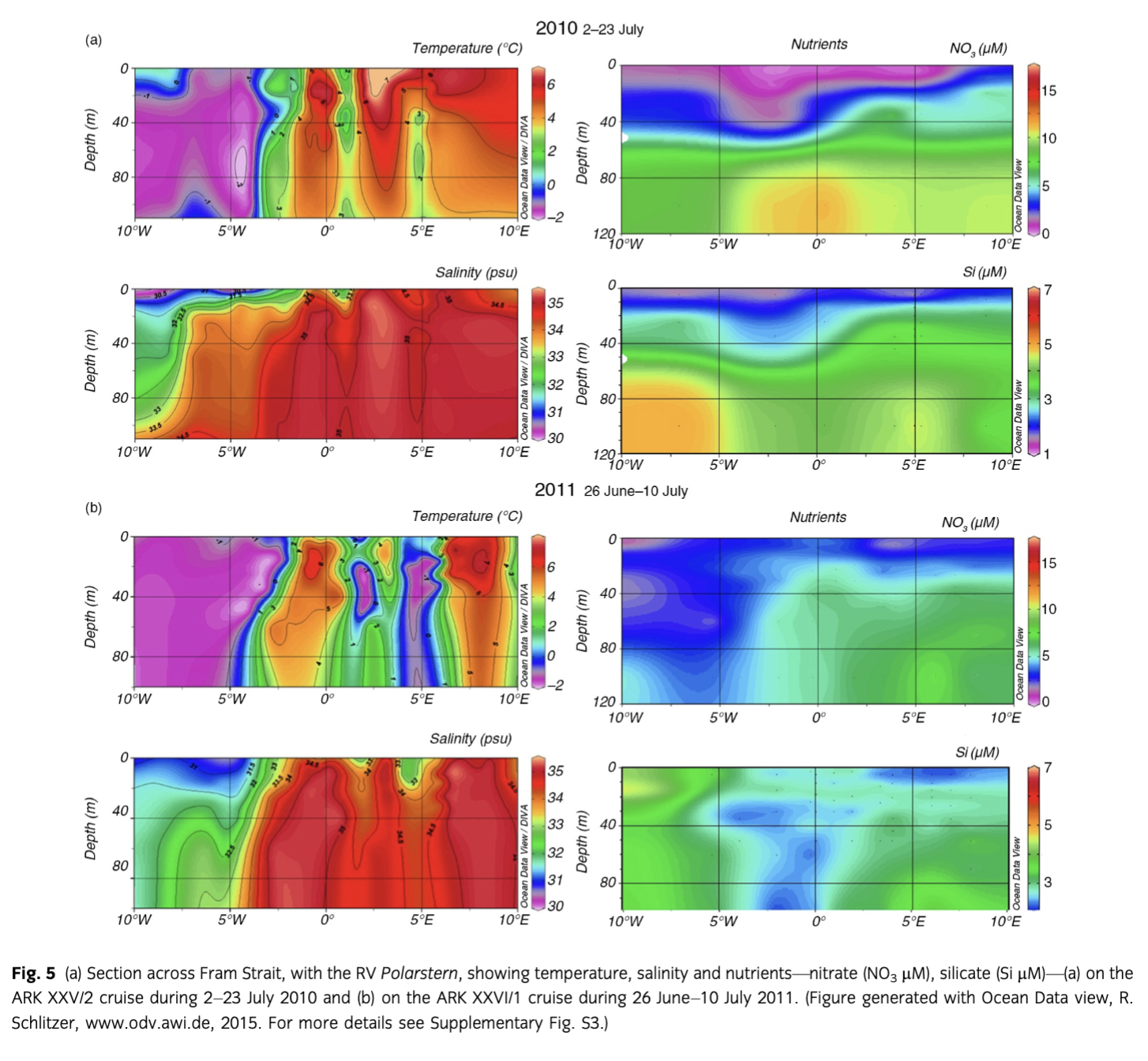

Ice concentration, water temperature, salinity and nutrients

Daily sea-ice concentration maps were provided by the Physical Analysis of Remote Sensing Images Group (PHAROS) of the University of Bremen (Spreen et al. 2008). Sea-ice concentration data were retrieved from the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer–Earth Observing System (AMSR-E) data with a spatial resolution of 6.25 km. Satellite chl a level-3 data were retrieved from the GlobColour archive (www.hermes.acri.fr). Temperature and salinity data were obtained with a CTD probe and retrieved from the Pangaea database (www.pangaea.de/; Beszczynska-Möller & Wisotzki 2010, 2012). To analyse inorganic nutrients (P, Si, N), seawater (50 mL) was obtained from 5–8 depths ranging between 2 and 100 m with a CTD rosette seawater sampling system equipped with 24 Niskin bottles. Subsamples were measured with an Evolution 3 auto-analyser (Alliance Instruments, Frepillon, France) according to Grasshoff et al. (1999).

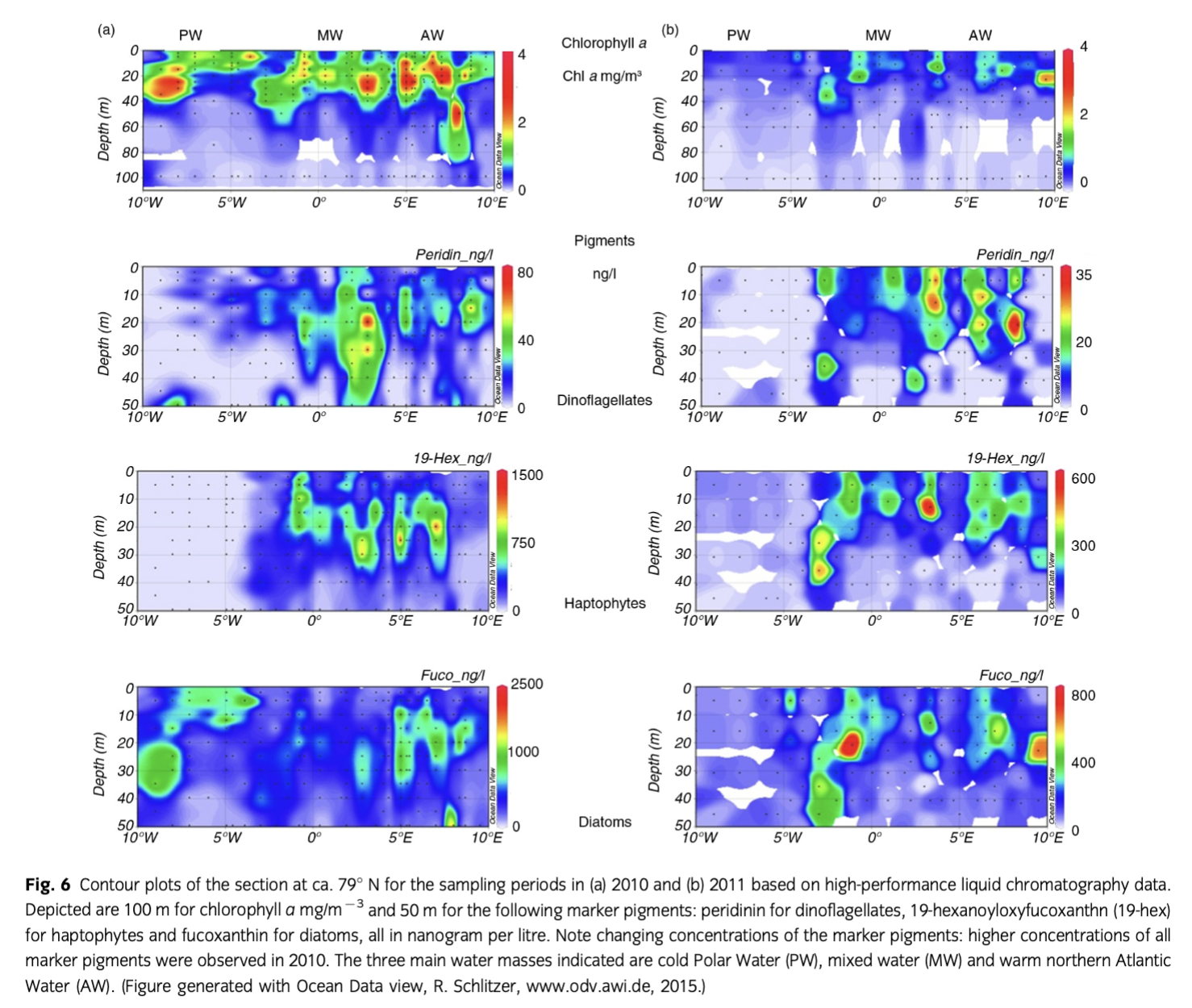

Pigments

Seawater (0.5–2.0 L, from 8–12 depths from surface to 100-m water depth) was filtered through Whatman GF/F filters, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C prior to analysis. Chl a, fucoxanthin, 19-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin and peridinin were measured with a Waters high-performance liquid chromatography system (Milford, MA, USA) in 2010 and 2011; for details, see Tran et al. (2013). Chl a was used as a biomass indicator, while the marker pigments fucoxanthin, 19-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin and peridinin were used as indicators of diatoms, haptophytes and autotroph dinoflagellates, respectively (Jeffrey & Vesk 1997).

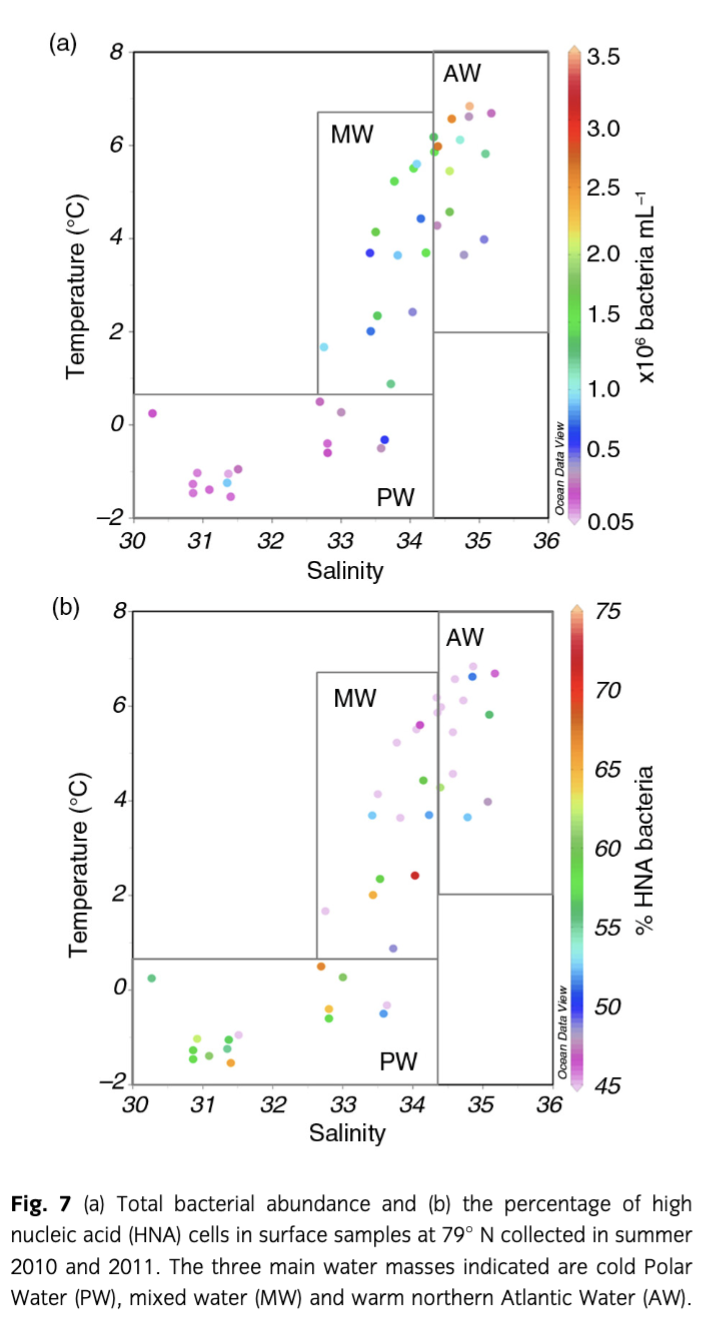

Bacterial abundance

For the determination of bacterial abundances, surface samples were collected at ca. 79° N in summer 2010 and 2011. Bacterial cell numbers were distinguished by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur platform (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) after staining with the DNA binding dye SYBR Green I (Invitrogen–Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Samples were fixed on board with glutardialdehyde at 2% final concentration and stored at −20°C until analysis within four months. Bacterial cell numbers were estimated after visual inspection and manual gating of the bacterial population in the cytogram of side scatter versus green fluorescence. Fluorescent latex beads (BD Biosciences and Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA) were used to normalize the counted events to volume (Gasol & del Giorgio 2000). Cytograms revealed two subpopulations with different levels of green fluorescence intensity proportional to the cellular nucleic acid content. Accordingly, the proportion of cells with high nucleic acid (HNA) was quantified (Robertson & Button 1989; Sherr et al. 2006; Bouvier et al. 2007).

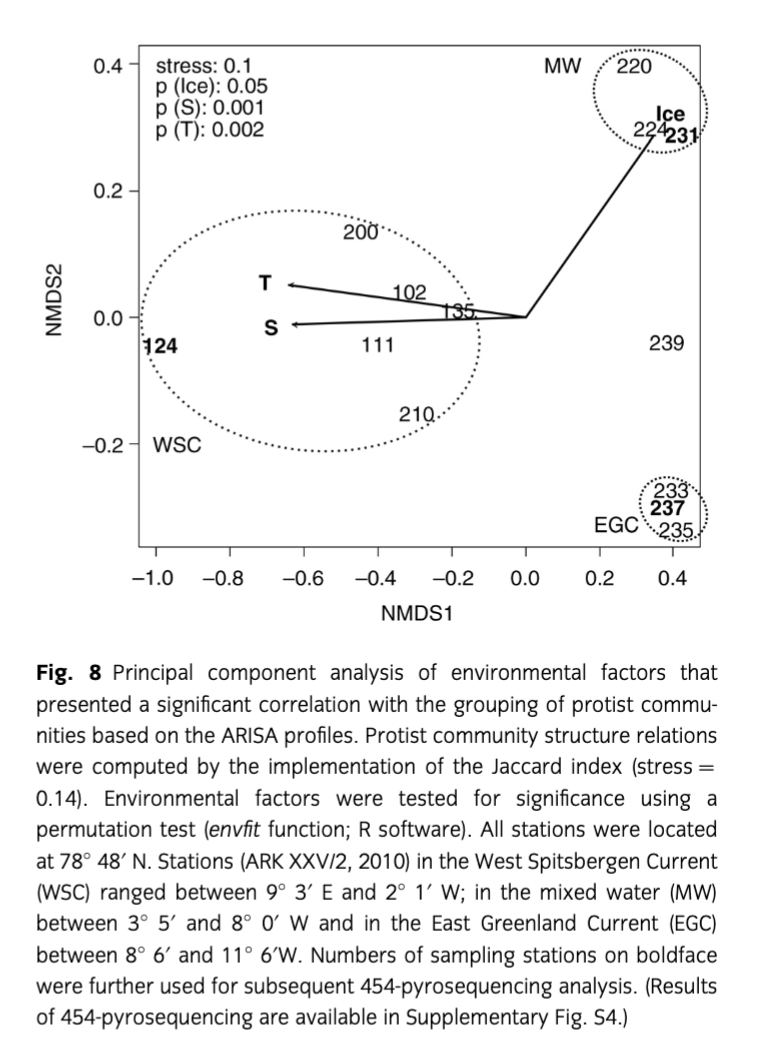

Ribosomal DNA–based protist community structure

Protist communities including the pico- and nanoplankton species were assessed with automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis (ARISA) and 454-pyrosequencing. ARISA is based on analysing the size of intergenic spacer regions of the ribosomal operon from different DNA fragments. The composite of the resulting differently sized DNA fragments in a sample is a characteristic fingerprint of a microbial community (e.g., Wolf et al. 2013). To assess the protist communities with comparatively low effort, but with high resolution based on sufficient deep taxon sampling, 454-pyrosequencing was applied (Margulies et al. 2005; Stoeck et al. 2010). The use of molecular techniques for species identification allows investigations of protist communities including rare species previously missed by the classical approaches (Sogin et al. 2006).

Samples for the molecular assessment of protist communities were collected at the chl a maximum along the transect at 78° 50′ N across northern Fram Strait. Two-litre water subsamples were transferred into polycarbonate bottles for subsequent filtration. In order to obtain a best possible representation of all cell sizes in the molecular approach, protist cells were collected immediately by fractionated filtration (200 mbar low pressure), through Millipore isopore membrane filters (Billerica, MA, USA) with pore sizes of 10 µm, 3 µm and 0.4 µm. Filters were then transferred into Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80°C until further processing. DNA extraction of each filter was carried out with an Omega Bio-Tek E.Z.N.A SP Plant DNA Kit, dry specimen protocol (Norcross, GA, USA). Genomic DNA was eluted from the column with 60-µl elution buffer. Extracts were stored at −20°C until further processing.

Initially, identical DNA volumes of each size class (10 µm, 3 µm and 0.4 µm) of each sample were pooled for the ARISA. The analyses were carried out as described by Kilias et al. (2013). The resulting data were converted to a presence/absence matrix, and differences in the phytoplankton community structure represented by differences in the respective ARISA data sets were determined by calculating the Jaccard index with an ordination of 10 000 restarts under the implementation of the Vegan package (Oksanen 2011). Multidimensional scaling plots were computed and possible clusters were identified using the hclust function of the Vegan package. An analysis of similarity test was conducted to test the significance of the clustering. A Mantel test (10 000 permutations) was used to test the correlation of the protist community structure distance matrix (Jaccard) and the environmental distance matrix (Euclidean). For the Mantel test, the ade4 R package was applied (Dray & Dufour 2007). To assess the significance of the single environmental variables, a permutation test was calculated using the envfit function of the Vegan package. Subsequently, a PCA of the protist community and the significant environmental factor distances was performed (ade4 R package).

DNA extracts from three representative stations from EGC PW, WSC MW and WSC AW were subjected to 454 pyrosequencing. The analysis was carried out as described by Kilias et al. (2013).

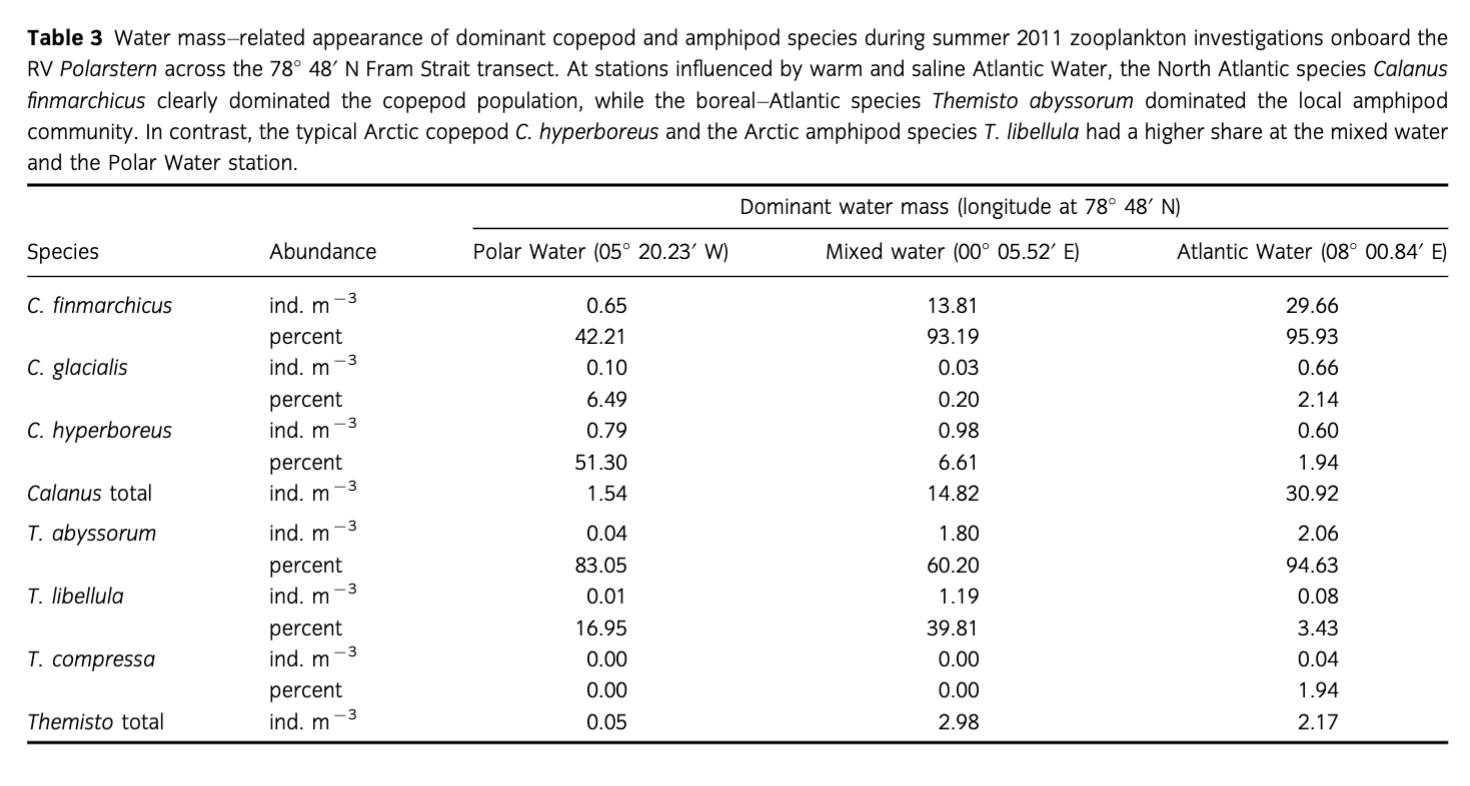

Zooplankton

The present study focusses on the three dominant calanoid copepod species of Fram Strait—Calanus finmarchicus, C. glacialis and C. hyperboreus—and on the amphipod family Hyperiidae, including the species Themisto compressa, T. abyssorum and T. libellula. These species are of different geographical origin and are associated with North Atlantic (C. finmarchicus and T. compressa), boreal (T. abyssorum), shelf (C. glacialis) and polar (C. hyperboreus and T. libellula) waters (Hirche et al. 1991; Koszteyn et al. 1995; Richter 1995; Mumm et al. 1998; Dalpadado 2002; Dalpadado et al. 2008).

Zooplankton sampling was started in 2011 along the transect at 78° 50′ N across northern Fram Strait. Depth-stratified samples were collected from 1000 m or the sea bed to the surface. Here the species composition of three stations, which were influenced by PW, MW and AW masses, is presented, respectively. To account for the different sizes of the target organisms, we used a Hydro-Bios (Kiel, Germany) Midi multiple closing net (net opening of 0.25 m2, 150-µm mesh size) for collecting mesozooplankton and a Hydro-Bios Maxi net (net opening of 0.5 m2, 1000-µm mesh size) for collecting macrozooplankton.

Samples were routinely collected from five depth ranges (0–50 m, 50–200 m, 200–500/600 m, 500/600–1000 m, 1000–1500 m), immediately transferred into buckets with cold seawater and brought to a cooling container (4°C). Some copepods, i.e., late copepodite stages, Calanus spp. adults and all amphipods of the family Hpyeriidae were sorted alive, identified to the species level under a Leica Microsystems MZ9 stereomicroscope (Wetzlar, Germany), counted, measured and stored deep-frozen for further analyses at the Alfred Wegener Institute home laboratory. The rest of each sample was preserved in 4% formaldehyde in seawater buffered with hexamethylentetramin. For species identification, specimens were sorted in Bogorov plates and identified under a Leica Microsystems MZ12.5 stereomicroscope (maximum magnification 100×). The two sibling Calanus species, C. finmarchicus and C. glacialis, were separated by means of prosome length measurements (Unstad & Tande 1991; Kwasniewski et al. 2003) with an ocular micrometer at a magnification of 10–25× (error 0.01–0.02 mm). Copepod nauplii were not determined to genus or species level, as they are not sampled quantitatively by a mesh size of 150 µm. Abundances of both copepods and amphipods were calculated as individuals per cubic metre.

Results

Long-term data

Satellite-derived chl a

Satellite-derived chl a expressed as monthly mean values for April to August from 1998 to 2012 for the EGC and WSC regions showed the typical seasonal variation (Fig. 2). However, the two regions showed slightly different variability and trends. In the EGC, the highest chl a concentration occurred in May or June, except in 2006, when the maximum concentration was reached in July. In the WSC, chl a peaked in June and July during the 2002–09 period; before and after that period, maximum chl a values were also reached during May or June. Overall, there was no significant trend of increase in chl a concentration in the EGC region (+0.19 mg chl a m−3 over all years; p value: 0.14), but the seasonal variability increased in recent years and the maximum chl a concentrations increased to values ranging between 1.5 and 2.0 mg m−3 for the period between 2009 and 2012, in contrast to 1–1.5 mg m−3 from 1998 to 2003, and 0.7–0.9 mg m−3 in 2002, 2004 and 2005. Whereas no significant increase in the chl a concentration was observed in the EGC, a significant increase of chl a (+0.54 mg m−3) occurred in the WSC (p<0.01) from 1998 to 2012. In both regions, the seasonal cycle (range between minimum and maximum chl a) was significantly enhanced after 2008 (Fig. 2).

Bloom duration was more variable and shorter in the ice-covered EGC region, ranging from 73 days in 2008 to 128 days in 1998, in contrast to the WSC region, which ranged from 112 days in 1998 to 142 days in 2006 and varied differently among years for the two regions (Supplementary Fig. S1).

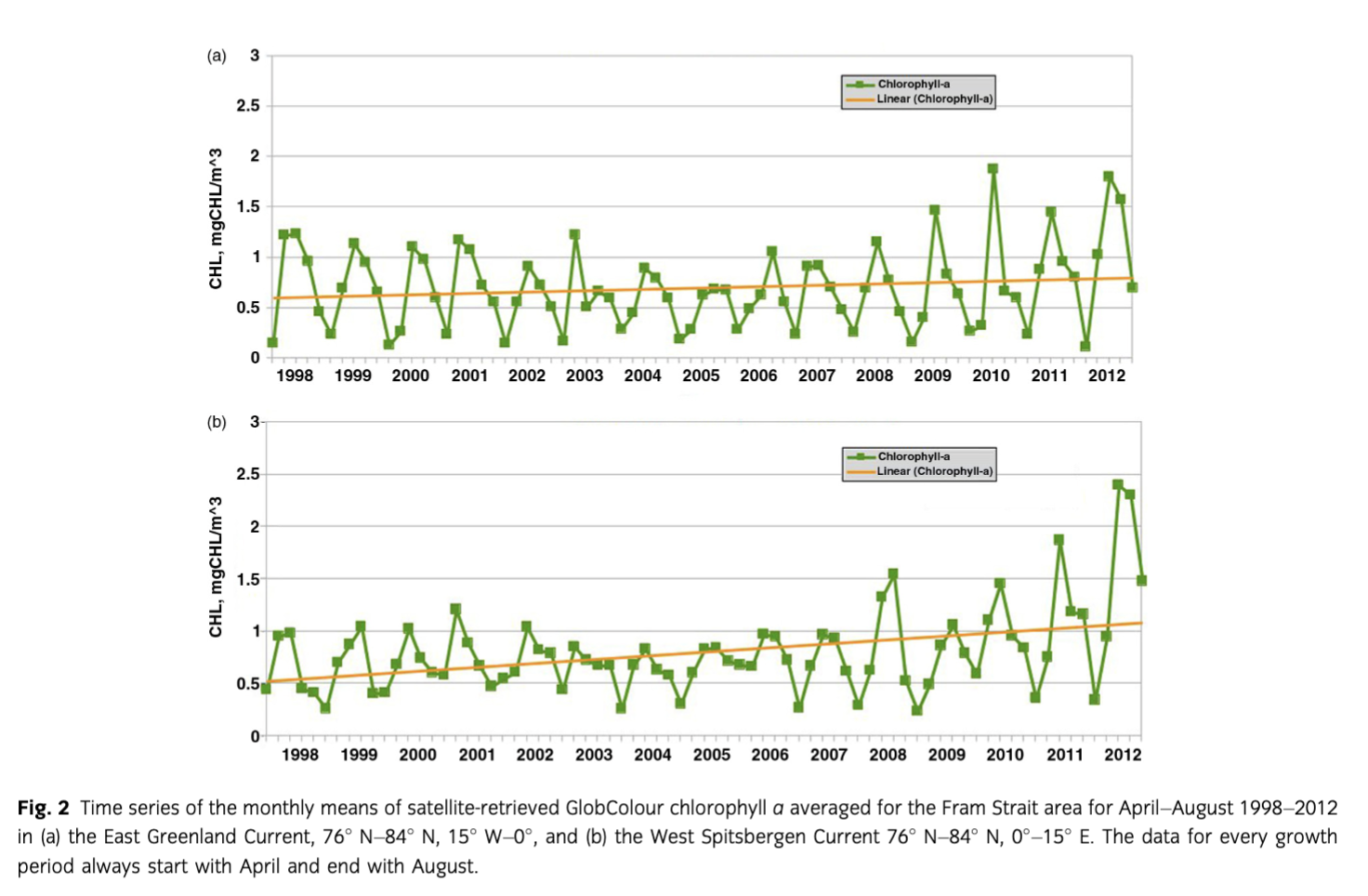

In situ chl a and protistian plankton species composition

In situ chl a—here given as one mean integrated (0–100 m) chl a m−2 value of all stations of each cruise—showed a trend towards higher concentrations from 1991 to 2012 in Fram Strait during the summer months. Those integrated mean summer chl a values showed similar trends as the satellite-derived chl a values. Integrated in situ chl a principally increased, although not significantly, in the WSC, while no such trend was observed in the EGC region (Fig. 3). The chl a concentrations measured in distinct depths (not shown) reached maximum values >4 mg m−3 during summer, mainly in subsurface waters below 10–20 m. In late summer, where only a small number of measurements of the long-term data sets were available, most values were below 0.1 mg m−3 and concentrations >1 mg m−3 were rare.

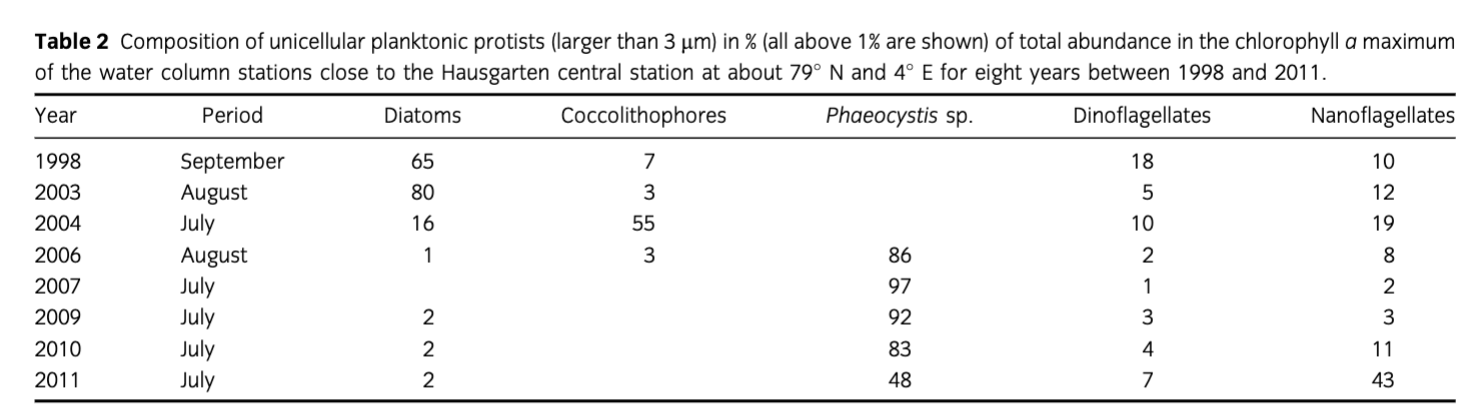

Protistian plankton (>3 µm) composition changed close to the Hausgarten central station in eastern Fram Strait from summer 1998 to summer 2011 (Table 2). Whereas diatoms, belonging mainly to the genera Thalassiosira, Chaetoceros and Fragilariopsis, prevailed from 1998 to 2003, coccolithophores, mainly Emiliania huxleyi, dominated in 2004. From 2006 onwards, Phaeocystis spp.—mainly P. pouchetii—increased in cell numbers and dominated the phytoplankton assemblages. In 2011, autotrophic and heterotrophic nanoflagellates were as abundant as P. pouchetii.

Table 2 Composition of unicellular planktonic protists (larger than 3 µm) in % (all above 1% are shown) of total abundance in the chlorophyll a maximum of the water column stations close to the Hausgarten central station at about 79° N and 4° E for eight years between 1998 and 2011. | ||||||

Year | Period | Diatoms | Coccolithophores | Phaeocystis sp. | Dinoflagellates | Nanoflagellates |

1998 | September | 65 | 7 |

| 18 | 10 |

2003 | August | 80 | 3 |

| 5 | 12 |

2004 | July | 16 | 55 |

| 10 | 19 |

2006 | August | 1 | 3 | 86 | 2 | 8 |

2007 | July |

|

| 97 | 1 | 2 |

2009 | July | 2 |

| 92 | 3 | 3 |

2010 | July | 2 |

| 83 | 4 | 11 |

2011 | July | 2 |

| 48 | 7 | 43 |

Multidisciplinary studies, summer 2010 and 2011

Ice concentration, water temperature, salinity and nutrients

During both years, the upper 100 m of the water column could be separated into three zones: the region west of ca. 3° W with PW, a zone between ca. 3° W and 5° E with a mixture of warm and cold water masses (MW), and east of ca. 5° E where warm AW prevailed. Sea-ice cover was nearly similar in 2010 and 2011 (Fig. 4) although slightly less and thinner sea ice was observed from June to August in 2010 in PW (Supplementary Fig. S2). Water temperatures in MW were lower in July 2011 than in 2010 (Fig. 5). Salinity was similar both years in AW, MW and PW, except for slightly lower salinity values in PW in 2010, which indicated intensified melting in the upper 20 m (Fig. 5). Lower nutrient concentrations were observed in AW in 2010 (Fig. 5); however, nitrate depletion only occurred at a few stations. There was no complete drawdown of nutrients in the upper 50 m of the water column during both years along the Fram Strait transect (Supplementary Table S3). However, nitrate concentrations were below the detection limit in the upper 20 m at half of the stations in 2010. The three different water masses encountered in the upper 100 m along the transect were reflected in the temperature/salinity and temperature/chl a diagrams (Supplementary Fig. S3), representing three different habitats for plankton communities.

Satellite-derived chl a

The data presented here originate from a closer look at the long-term monthly averaged satellite-derived chl a data. Chl a values peaked in June in 2010 and 2011 (Fig. 2). In 2010, the peak was higher in the EGC (ca. 1.9 chl a m−3) than in the WSC (ca. 1.5 chl a m−3). The opposite situation was observed in 2011, with higher chl a peaks in the WSC (ca. 1.9 chl a m−3) than in the EGC (ca. 1.5 chl a m−3). Lower chl a values were observed in July 2010 compared to July 2011 in both regions (ca. −0.3 mg m−3). However, chl a values in July were higher in the WSC than in the EGC.

The duration of the bloom in 2011 was the same (120 days) in both regions, but quite different in 2010 (137 days in the WSC and 102 days in the EGC; Supplementary Fig. S1). The onset of the blooms in the WSC occurred at nearly the same time both years (at day 105 and 116, respectively) and over three weeks later in the EGC in 2010 (at day 138) as compared to 2011 (at day 116).

In situ chl a

The pronounced bloom estimated by satellite in 2010 was confirmed with in situ chl a sampling (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S3a). However, our sampling during the cruises occurred slightly after the main increase in the surface waters. Deep maxima could be observed for the in situ chl a concentration. Those concentrations were somewhat higher than the mean of the surface values observed by satellite during both cruises. Maximum values of chl a concentrations were >4 mg m−3 in 2010 and the maximum never exceeded 2.5 mg m−3 during the cruise in 2011. The lack of chl a at the surface of various stations and the enhanced subsurface maximum was likely caused by the depletion of nitrate during 2010. The 2011 cruise occurred one week earlier and was shorter than the 2010 cruise.

Pigments

The vertical and horizontal small-scale sampling of pigments conducted during 2010 showed the co-occurring bands of organisms groups with water parcels of the three different water masses (Fig. 6). A distinct separation was obvious among PW, MW and AW. While the diatom marker fucoxanthin was present in all three domains, it dominated at the ice edge in 2010. In contrast, the dinoflagellate marker peridinin dominated in MW. The high concentration of 19-hexanoyl-oxyfucoxanthin, mainly in AW, indicated the presence of haptophytes. In 2011, its relative proportion was higher, reflecting the presence of haptophytes, here mainly of Phaeocystis species. The high concentrations of fucoxanthin and 19-hex below 40 m at the border between PW and MW in 2011 indicated the downward transport of a decaying bloom in the MW zone.

Bacterial abundance

Bacterial abundances were clearly different among AW, MW and PW in summer 2010 and 2011 (Fig. 7). Average cell numbers of 1.2×106 cells mL−1 in AW were roughly five times higher than in PW, where bacterial abundances ranged from 6.0×104 cells mL−1 to 9.0×105 cells mL−1; bacterial abundances in MW ranged between the values in PW and AW, indicating the mixed character of this water mass (Fig. 7a). The percentage of HNA cells showed the opposite trend. On average, HNA cells contributed 56% to total bacterial abundances in both PW and MW but only 44% in AW (Fig. 7b). Bacterial abundances were significantly higher in 2010 than in 2011 in both AW (t-test, n=27, p<0.001) and PW (Mann–Whitney rank sum test, n=9, p=0.024); here again the values in MW reflected the intermediate nature of this water mass. In contrast, proportions of HNA bacteria were significantly higher in 2011 than in 2010 in both water masses (AW: t-test, n=27, p<0.001; PW: t-test, n=9, p=0.038).

Ribosomal DNA–based protist community structure

Automated ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis of 14 samples from the 2010 cruise resulted in 252 different PCR fragments. Based on Jaccard’s distances, the ARISA profiles grouped into three significantly distinct clusters in a meta-multidimensional scaling plot (Fig. 8). The community profiles within a cluster were more similar to each other than to the community profiles of the other clusters. The clustering is supported by an analysis of similarity test (R=1, p=0.001). The biggest cluster was composed of eight samples that were all located in the AW of the WSC. A second cluster was composed of three stations originating from the MW zone between AW and PW, and a third cluster contained three samples, originating from the PW of the EGC. Distances of the ARISA profiles are significantly correlated with the ones of the environmental factors (temperature, salinity and sea-ice cover), computed by the Euclidean index (Mantel test: p=0.001). Temperature and salinity presented a higher significance (p=0.002) than ice coverage (p=0.018). The PCA of both profiles reveals that samples from the AW are primarily distinguished from the other clusters (MW and PW) by higher temperature and salinity, but lower ice coverage. The separation of the MW and the PW clusters was not based on the investigated environmental parameters. Monoclonal cultures taken for genetic analyses of Phaeocystis pouchetii also showed a zonation of different clones for the different regions. Protist communities originating from different water bodies in Fram Strait were further elucidated by sequencing the V4 region of the 18S rDNA using 454-pyrosequencing. We analysed one representative samples from each water body. Overall, we identified 233 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of 3977 total sequences (AW), 361 OTUs of 10 995 total sequences (PW) and 659 OTUs of 17 372 total sequences (MW). The genetic diversity of the protist communities was different at all three stations (Supplementary Fig. S4). Diatoms prevailed in PW and dinoflagellates in MW, and in AW a mixture of haptophytes, dinoflagellates and diatoms was found. In detail, the composition of protistian plankton in PW showed a high abundance of stramenopiles (ca. 83%) that were mainly composed of centric (76.7%) and some pennate diatoms (4.4%). Other abundant taxonomic groups were haptophytes and dinophytes, dominated by Phaeocystis pouchetii (8.6%) and Gyrodinium sp. (2.3%), respectively. In contrast, the MW station presented a protist community that was strongly dominated by alveolates (ca. 93%), particularly dinophytes (77.5%). The WSC station (AW) was characterized by a more balanced community structure. In descending relative abundances, haptophytes (40.3%) and alveolates (30.9%) accounted for the highest contributions, followed by chlorophytes (13.2%), stramenopiles (9.9%) and cryptophytes (2.4%). Haptophytes were represented by P. pouchetii (28.6%) and P. cordata (8.5%), and chlorophytes showed two abundant phylotypes such as the picoeukaryote species Micromonas pusilla (6.5%) and Bathycoccus prasinos (4.7%). Stramenopiles presented just one abundant phylotype that was classified as a pennate diatom (3.2%) but could not be characterized in more detail.

Zooplankton

The highest abundances of Calanus spp. and Themisto spp. were observed in the surface layers at the MW and AW stations with 15 and 31 ind. M−3 of Calanus spp., and three and two ind. m−3 of Themisto spp., respectively. The species composition also differed among stations. At the PW station, the Arctic deep-water copepod Calanus hyperboreus dominated the Calanus community, contributing 51%. At stations influenced by warm and saline AW, temperature >3°C and salinity >34.9 psu, the North Atlantic species C. finmarchicus clearly dominated the population, with up to 95.9% (Table 3). The Arctic shelf species C. glacialis was generally found in low numbers, contributing at maximum 6.5% to the population at the PW station. Similarly, the boreal–Atlantic species Themisto abyssorum dominated the local amphipod population (94.6%) at the station influenced by AW, whereas T. libellula, typical of the Arctic, had a higher share at the MW and the PW station. In addition, the North Atlantic species T. compressa occurred only at the easternmost AW station (Table 3).

Discussion

The Arctic Ocean experienced severe changes in temperatures and sea ice during the last decade (e.g., Symon et al. 2005; Maslanik et al. 2007; Solomon et al. 2007; Comiso et al. 2008; Maslanik et al. 2011; Comiso 2012). These environmental changes will likely have consequences for the biogeochemistry and ecology of the Arctic pelagic system (e.g., Piepenburg & Bluhm 2009; Weslawski et al. 2009; Bluhm et al. 2011; Wassmann 2011). Major impacts are expected for species composition, the pelagic food web, elemental and matter fluxes, i.e., carbon sequestering (e.g., Fortier et al. 2002; Hirche & Kosobokova 2007; Li et al. 2009; Morán et al. 2010; Hilligsøe et al. 2011; Lalande et al. 2011; Wassmann & Reigstad 2011; Engel et al. 2013). Warming and rapid decrease in sea-ice extent and thickness in the Arctic Ocean eventually have an impact on primary productivity, species composition and thus on carbon export (Arrigo et al. 2011; Wassmann 2011; Arrigo et al. 2012; Boetius et al. 2013). Some observations already indicate an alteration. Primary production increased by 20% on average from 1998 to 2009 (Arrigo et al. 2008; Arrigo & Dijkin 2011), and the freshening of Arctic surface waters seems to promote growth of picoplankton (Li et al. 2009).

However, the Fram Strait area is affected in a different manner than the central Arctic Ocean since here warm AW and cold PW meet and partly mix. Because of its geographic position, Fram Strait is a permanent outlet for Arctic Ocean sea ice via the Transpolar Drift. This transport of sea ice varies but ice area export increased by 25% since the 1960s due to stronger geostrophic winds, with particularly high values during 2005–2008 (Smedsrud et al. 2011). Whereas time series studies showed that in some regions phytoplankton blooms occur earlier because of the Arctic-wide seasonal sea-ice decrease (e.g., Wassmann & Reigstad 2011), at Fram Strait, only a minor change or even delay in phytoplankton bloom timing was recorded (Kahru et al. 2011; Harrison et al. 2013).

Consistent with earlier observations, our results show that only minor changes in bloom timing and duration occur in Fram Strait, but we see in the satellite data that the seasonal variability in the shallow upper water layers has recently increased. Although satellite-derived data can only describe the upper metres of the water column, we can confirm most of our arguments with the in situ data sets, except for very deep maxima (Cherkasheva et al. 2013; Cherkasheva et al. 2014). Furthermore, our long-term satellite-derived and in situ chl a data sets reveal that the EGC and WSC regions showed different variability and trends (Figs. 2, 3, Supplementary Fig. S1). In general, chl a values stayed relatively constant during the last 20 years (1991 to 2012) in Fram Strait and Greenland Sea, similar to the estimations of primary productivity of Wassmann et al. (2010). However, a minor increase in satellite-derived surface and in situ chl a (integrated for the upper 100 m water column) was observed in the warm AW of the WSC. These trends point to an increase in phytoplankton biomass concomitant with warmer AW entering eastern Fram Strait. A recent study of satellite-retrieved chl a concentrations from temporarily ice-free zones validated with in situ data indicated a regional separation of physical processes affecting phytoplankton distribution in Fram Strait (Cherkasheva et al. 2014; this study). Temperature is one of them, but ice and stratification also play a role. During the 12 years of observations, chl a concentrations increased in the southern part of Fram Strait in conjunction with an increase in sea-surface temperature and a decrease in Svalbard coastal ice (Cherkasheva et al. 2014). Whereas no substantial changes were observed over the ice-covered EGC by satellite nor in situ data, an overall increase of 0.4 mg chl a m−3 in the eastern part of Fram Strait was derived from satellite data, and is supported by an increasing phytoplankton biomass shown by in situ chl a measurements in the WSC. Like Reigstad et al. (2011), we did not see a strong change of biomass in the Svalbard area. In their model approach, primary production in the WSC from 1995 to 2007 seemed to have been slightly increased after the year 2000 but then declined again. The latter we cannot support with our investigations.

We cannot clearly prove that temperature is the only important factor influencing biomass and species composition in eastern Fram Strait. Nevertheless, temperature increase happens in the entire Atlantic Ocean and what we see in eastern Fram Strait is a “passing by” of warmer AW on its way towards the Arctic Ocean. The warming of Atlantic water masses also overlaps with two oscillation systems: the North Atlantic Oscillation and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. To distinguish warming trends from natural fluctuations, we need to observe the Fram Strait pelagic system on longer time scales. However, we argue that we see differences in the biomass and species composition coupled with the observed temperature increase and that this is possibly due to a change in water mass characteristics of the WSC over the last 20 years.

Viewed over the long-term, different water mass properties seem to be most responsible for increasing mean chl a concentrations in the WSC. On time scales of weeks, however, the amount of sea-ice cover in the western part of the investigation area, in combination with the hydrography of the WSC, influences bloom developments. In 2010, somewhat less sea ice was found during the months June through August. Nutrients, in situ chl a and phytoplankton species composition of our expedition in July 2010 showed that the bloom had occurred and a higher biomass was measured in 2010 compared to 2011. Besides sea-ice cover, another reason for differences between the results of the two summer cruises might be that the 2011 cruise occurred one week earlier and was shorter than the 2010 cruise. From the satellite data, we see that in the western region the bloom occurred nearly one month earlier and reached higher values in 2010 compared to 2011. In the eastern region, higher maximum chl a occurred in 2011 than in 2010. This was only evident in the satellite data but not in the three weeks of our 2011 expedition. Nevertheless, the 2011 bloom in eastern Fram Strait seemed suppressed by the lower light conditions caused by ice cover. Furthermore, we assume the larger ice extent in 2011 did not allow diatoms to grow early or to grow in the far west.

Regarding the long-term data, complex physical interactions seem to also have considerable influence on the species composition and distribution in the Fram Strait region. In 2004, a remarkable change in the phytoplankton species composition from a dominance of diatoms to a dominance of coccolithophores, mainly the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi, occurred close to the Hausgarten central station. This shift was also observed both in the water column and in the yearly-deployed long-term sediment trap series of Bauerfeind et al. (2009). In the sediment trap samples, we found increasing numbers of E. huxleyi starting in the year 2000 until 2004. After that period, they disappeared again. Hegseth & Sundfjord (2008) also reported an E. huxleyi bloom north-east of Spitsbergen in summer 2003, which was transported with the WSC far in that northern region. The dominance of coccolithophores was not observed again and was eventually replaced by the haptophyte Phaeocystis pouchetii. However, P. pouchetii is an organism that is almost unrecognizable in sediment trap samples with a microscope. Nevertheless, combining our long-term data from the water column and sediment traps samples (Bauerfeind et al. 2009; Bauerfeind & Nöthig et al. unpubl. data) suggests a shift in species composition during summer months between 2005 and 2007, during the warm anomaly event of the AW, with an increase in flagellates after that period, mainly by the colony-forming P. pouchetii.

Interestingly, P. pouchetii biomass continued to increase from 2006 to 2012, although the temperature of AW passing eastern Fram Strait decreased slightly. In 2012, a massive bloom was observed (Nöthig et al. unpubl. data). Massive blooms of P. pouchetii were also observed in 2006 and 2007 in Kongsfjorden (Hegseth & Tverberg 2013) and in Fram Strait (Saiz et al. 2013). Diatoms seem to become of minor importance particularly during summer in eastern Fram Strait. The long-term deployed sediment trap samples from the Hausgarten central station underline this trend by showing a decrease in the flux of biogenic silica, a proxy for diatoms (Lalande et al. 2013). Diatoms also did not increase their biomass as they usually did during May in Kongsfjorden in the study of Hegseth & Tverberg (2013). The reasons for this phenomenon remain unclear. Phaeocystis blooms occurred although silicate concentrations were still sufficient for diatom growth.

Phaeocystis pouchetii in high abundances in the marginal ice zone have also been reported during the 1980s–1990s (Smith et al. 1987; Gradinger & Baumann 1991). So Phaeocystis blooms are not a new feature in this region. The lack of early long-term observations in eastern Fram Strait makes it impossible to determine if the increase observed during 2006 was due to climate change. However, species composition of the swimmers (zooplankton that actively enters sediment trap samples) collected in the long-term sediment traps at the central station at Hausgarten supports the assumption of a shift in species composition for the summer periods. During the warm anomaly in 2004–2007, a change in the dominant pteropod species was observed, from Limacina helicina, the cold-water form, to L. retroversa, the Atlantic species (Bauerfeind et al. 2014; Busch et al. 2015). This trend is still continuing. Kraft et al. (2013) reported the first evidence of successful reproduction in Fram Strait of Themisto compressa, an Atlantic pelagic crustacean. Themisto compressa was also shown to have expanded its range from more southerly and warmer waters from 2004 onwards (Kraft et al. 2013).

In the course of our observation, nano- and picoplankton have increased in importance at the central station in Hausgarten during the summers (Bauerfeind et al. 2009; Mebrahtom Kidane 2011; this study; Bauerfeind & Nöthig et al. unpubl. data). Cascading effects on all trophic levels from the euphotic zone to the deep sea are expected. Therefore, starting in 2009, the annual sampling campaigns in Fram Strait were complemented with microbiological and molecular assessments of nano- and picoplankton and bacteria. Those short-term investigations show a clear separation in the distribution of species composition in the three prevailing surface water masses in Fram Strait. Distinct communities in waters of Arctic and Atlantic origin were identified and suggest that less ice-coverage and higher water temperatures favour the abundances of, for example, picoeukaryotes dominated by the chlorophyte Micromonas sp. (Kilias et al. 2013; Kilias et al. 2014).

Bacterial abundances in AW and PW were significantly different between the summers of 2010 and 2011, suggesting a substantial influence of interannual variability in seawater temperature, sea-ice cover and phytoplankton biomass on bacterial growth. Interestingly, the proportion of HNA was also different among the different water masses and the two consecutive years. The proportion of HNA cells in Arctic bacterioplankton communities was shown to increase during spring, a few weeks after phytoplankton growth resumed (Belzile et al. 2008; Seuthe et al. 2011). Many field and laboratory studies show that the HNA subgroup in bacterioplankton communities is responsible for the largest share of bulk activity (Lebaron et al. 2001; Servais et al. 2003). Also in Fram Strait at 79° N, direct relationships between the proportion of HNA cells and cell-specific metabolic rates support this interpretation of a metabolically very active HNA subpopulation (Piontek et al. 2014).

A considerable alteration of the zooplankton community is expected if the general warming trend in the Arctic Ocean persists and biogeographic boundaries of zooplankton species shift (Falk-Petersen et al. 2007; Hirche & Kosobokova 2007, Weslawski et al. 2009). Accordingly, we have already observed a decrease in polar species and an increase in boreal species in the swimmer fraction of sediment trap samples from Fram Strait (Kraft et al. 2011; Kraft et al. 2012; Kraft et al. 2013; Bauerfeind et al. 2014). However, in summer 2011 the observed mesozooplankton community structure—with a pronounced numerical dominance of copepods—was in accordance with results reported from earlier investigations (e.g., Richter 1995; Hop et al. 2006; Blachowiak-Samolyk et al. 2007), although detailed studies of changing zooplankton communities are rare. In 2011, more sea ice and colder water was observed mainly in the MW domain than during 2010. This could explain the occurrence of the cold-adapted Themisto libellula in MW in 2011 as well as the relatively low numbers of copepod species in the WSC compared to earlier studies (Hop et al. 2006). Until now, only a few recent investigations have focussed on possible effects of physical change in the environment on composition and structure to mesozooplankton communities around Svalbard (Blachowiak-Samolyk et al. 2007; Trudnowska et al. 2012).

Also, the performance of Calanus spp., which dominates zooplankton communities at high latitudes, could change in the future with changing environmental conditions. Long-term incubations of C. hyperboreus indicated that higher temperatures during over-wintering led to higher losses in body mass and earlier reproduction, while elevated CO2 concentrations had no effect (Hildebrandt et al. 2014). The shift in the phytoplankton community composition could probably influence copepod diversity growth and reproduction. Data on trophic flexibility of most species are scarce, and there is an urgent need for studies assessing the response of the calanoid copepods to a changing food regime, i.e., the shift from diatoms to smaller flagellates (Bauerfeind et al. 2009).

Concluding remarks and outlook

Long-term sampling was carried out for almost 20 years in Fram Strait, and for 14 years for the Alfred Wegener Institute’s Hausgarten project. Starting with traditional methods, such as water sampling, microscope counts and bulk measurements (e.g., chl a), we have now added modern approaches, such as microbiological and molecular tools as well as high-performance liquid chromatography, flow cytometry and optical measurements, in order to determine the bacteria and phytoplankton of all size classes in more detail and at better resolution. In addition, net sampling for zooplankton studies has been included recently to understand the reaction of higher trophic levels to changes in food supply. With this approach, we established a baseline in the summer of 2010 and 2011 for a larger variety of parameters ranging from bacteria to pico-, nano- and microplankton and to larger zooplankton. The continuous observation of the different compartments of the pelagic foodweb in the coming years will give detailed answers in regard to changes due to global climate change or natural variability in both regimes, polar and Atlantic, in Fram Strait. Effects of changing environmental conditions on heterotrophic plankton in Fram Strait will be decisive for the phytoplankton diversity and productivity and, therefore, for potential changes in carbon cycling. Effects of climate change on the balance between autotrophic carbon production and heterotrophic carbon transformation and remineralization in microbial food webs would have a high potential to change export fluxes of organic carbon in the future Arctic Ocean. Our goal is to continue our long-term sampling to evaluate and detect further changes in the biota of the different water masses of Fram Strait. (More outlook details are found in the Supplementary File.)

Acknowledgements

We thank the captains and crew of the RVs Polarstern, Maria S. Merian and Lance for their support during all cruises. We thank N. Knüppel, C. Lorenzen, S. Murawski, A. Nicolaus, K. Oetjen, A. Schröer and S. Wiegmann for excellent technical support in the laboratory and many student helpers for their assistance during cruises and in the laboratory. We also thank F. Kilpert and B. Beszteri for their support in bioinformatics for the molecular and biological analyses. This work was partly supported by the POLMAR Helmholtz Graduate School for Polar and Marine Research and by the Helmholtz Impulse and Network Fund at the Alfred Wegener Institute (Phytooptics and Planktosens projects). This study was also partly financed by institutional funds of the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (project BMBF 03F0629A) as well as the Deutsche Forschungs Gemeinschaft. Oceanographic data were retrieved from the Alfred Wegener Institute’s Pangaea data bank (doi:10.1594/pangaea.754250; doi:10.1594/pangaea.774196). Satellite data were provided by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (SeaWiFS, MODIS), the European Space Agency (MERIS, GlobColour) and the PHAROS group of University of Bremen. The work was carried out by the Plankton Ecology and Biogeochemistry in a Changing Arctic Ocean (PEBCAO) group.

References

- Arrigo K.R. & Dijkin G.V. 2011. Secular trends in Arctic Ocean net primary production. Journal of Geophysical Research—Oceans 116, C09011, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007151 Publisher Full Text

- Arrigo K.R., Dijkin G.V. & Pabi S. 2008. Impact of a shrinking Arctic ice cover on marine primary production. Geophysical Research Letters 35, L19603, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2008GL035028 Publisher Full Text

- Arrigo K.R., Matrai P.A. & van Dijken G.L. 2011. Primary productivity in the Arctic Ocean: impacts of complex optical properties and subsurface chlorophyll maxima on large-scale estimates, Journal of Geophysical Research—Oceans 116, C11022, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2011JC007273 Publisher Full Text

- Arrigo K.R., Perovich D.K., Pickart R.S., Brown Z.W., van Dijken G.L., Lowry K.E., Mills M.M., Palmer M.A., Balch W.M., Bahr F., Bates N.R., Benitez-Nelson C., Bowler B., Brownlee E., Ehn J.K., Frey K.E., Garley R., Laney S.R., Lubelczyk L., Mathis J., Matsuoka A., Mitchell B.G., Moore G.W., Ortega-Retuerta E., Pal S., Polashenski C.M., Reynolds R.A., Schieber B., Sosik H.M., Stephens M. & Swift J.H. 2012. Massive phytoplankton blooms under Arctic sea ice. Science 336, 1408. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Bauerfeind E., Garrity C., Krumbholz M., Ramseier R.O. & Voß M. 1997. Seasonal variability of sediment trap collections in the Northeast Water Polynya. Part 2. Biochemical and microscopic composition of sedimenting matter. Journal of Marine Systems 10, 371–389. Publisher Full Text

- Bauerfeind E., Nöthig E.-M., Beszczynska A., Fahl K., Kaleschke L., Kreker K., Klages M., Soltwedel T., Lorenzen C. & Wegner J. 2009. Particle sedimentation patterns in the eastern Fram Strait during 2000–2005: results from the Arctic long-term observatory Hausgarten. Deep-Sea Research Part I 56, 1471–1487. Publisher Full Text

- Bauerfeind E., Nöthig E.-M., Pauls B., Kraft A. & Beszczynska-Möller A. 2014. Variability in pteropod sedimentation and corresponding aragonite flux at the Arctic deep-sea long-term observatory Hausgarten in the eastern Fram Strait from 2000 to 2009. Journal of Marine Systems 132, 95–105. Publisher Full Text

- Belzile C., Brugel S., Nozais C., Gratton Y. & Demers S. 2008. Variations of the abundance and nucleic acid content of heterotrophic bacteria in Beaufort Shelf waters during winter and spring. Journal of Marine Systems 74, 946–956. Publisher Full Text

- Beszczynska-Möller A., Fahrbach E., Schauer U. & Hansen E. 2012. Variability in Atlantic water temperature and transport at the entrance to the Arctic Ocean, 1997–2010. ICES Journal of Marine Science 69, 852–863. Publisher Full Text

- Beszczynska-Möller A. & Wisotzki A. 2010. Physical oceanography during Polarstern cruise ARK-XXV/2. Bremerhaven: Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research, Alfred Wegener Institute. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1594/pangaea.754250

- Beszczynska-Möller A. & Wisotzki A. 2012. Physical oceanography during Polarstern cruise ARK-XXVI/1. Bremerhaven: Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research, Alfred Wegener Institute. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1594/pangaea.774196

- Blachowiak-Samolyk K., Kwasniewski S., Dmoch K., Hop H. & Falk-Petersen S. 2007. Trophic structure of zooplankton in the Fram Strait in spring and autumn 2003. Deep-Sea Research Part II 54, 2716–2728. Publisher Full Text

- Bluhm B.A., Gebruk A.V., Gradinger R., Hopcroft R.R., Huettmann F., Kosobokova K.N., Sirenko B.I. & Weslawski J.M. 2011. Arctic marine biodiversity: an update of species richness and examples of biodiversity change. Oceanography 24, 232–248. Publisher Full Text

- Boetius A., Albrecht S., Bakker K., Bienhold C., Felden J., Fernández-Méndez M., Hendricks S., Katlein C., Lalande C., Krumpen T., Nicolaus M., Peeken I., Rabe B., Rogacheva A., Rybakova E., Somavilla R., Wenzhöfer F. & RV Polarstern ARK27-3-Shipboard 2013. Export of algal biomass from the melting Arctic sea ice. Science 339 1430–1432. Publisher Full Text

- Bouvier T., del Giorgio P.A. & Gasol J.M. 2007. A comparative study of the cytometric characteristics of high and low nucleic-acid bacterioplankton cells from different aquatic ecosystems. Environmental Microbiology 9, 2050–2066. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Busch K., Bauerfeind E. & Nöthig E.-M. 2015. Pteropod sedimentation patterns in different water depths observed with moored sediment traps over a 4-year period at the LTER station Hausgarten in eastern Fram Strait. Polar Biology 38, 845–859. Publisher Full Text

- Cherkasheva A., Bracher A., Melsheimer C., Köberle C., Gerdes R., Nöthig E.-M., Bauerfeind E. & Boetius A. 2014. Influence of the physical environment on polar phytoplankton blooms: a case study in the Fram Strait. Journal of Marine Systems 132, 196–207. Publisher Full Text

- Cherkasheva A., Nöthig E.-M., Bauerfeind E., Melsheimer C. & Bracher A. 2013. From the chlorophyll a in the surface layer to its vertical profile: a Greenland Sea relationship for satellite applications. Ocean Science 9, 431–445. Publisher Full Text

- Comiso J.C. 2012. Large decadal decline of the Arctic multiyear ice cover. Journal of Climate 25, 1176–1193. Publisher Full Text

- Comiso J.C.P., Parkinson C.L., Gersten R. & Stock L. 2008. Accelerated decline in the Arctic sea ice cover. Geophysical Research Letters 35, L01703, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2007GL031972 Publisher Full Text

- Dalpadado P. 2002. Inter-specific variations in distribution, abundance and possible life-cycle patterns of Themisto spp. (Amphipoda) in the Barents Sea. Polar Biology 25, 656–666.

- Dalpadado P., Ellertsen B. & Johannessen S. 2008. Inter-specific variations in distribution, abundance and reproduction strategies of krill and amphipods in the marginal ice zone of the Barents Sea. Deep-Sea Research Part II 55, 2257–2265. Publisher Full Text

- Dray S. & Dufour A.-B. 2007. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. Journal of Statistical Software 22, 1–20. Publisher Full Text

- Edler L. 1979. Recommendations on methods for marine biological studies in the Baltic Sea. Phytoplankton and chlorophyll. Baltic Marine Biologists Publication 5. Uppsala: Baltic Marine Biologists.

- Engel A., Borchard C., Piontek J., Schulz K., Riebesell U. & Bellerby R. 2013. CO2 increases 14C primary production in an Arctic plankton community. Biogeosciences 10, 1291–1308. Publisher Full Text

- Evans C.A., O’Reily J.E. & Thomas J.P. 1987. A handbook for measurement of chlorophyll a and primary production. College Station, TX: Texas A & M University.

- Falk-Petersen S., Timofeev S., Pavlov V. & Sargent J.R. 2007. Climate variability and the effect on Arctic food chains. In J.B. Ørbæk et al. (eds.): Arctic–alpine ecosystems and people in a changing environment. Pp. 147–161. Berlin: Springer.

- Forest A., Wassmann P., Slagstad D., Bauerfeind E., Nöthig E.-M. & Klages M. 2010. Relationships between primary production and vertical particle export at the Atlantic–Arctic boundary (Fram Strait, Hausgarten). Polar Biology 33, 1733–1746. Publisher Full Text

- Fortier M., Fortier L., Michel C. & Legendre L. 2002. Climatic and biological forcing of the vertical flux of biogenic particles under seasonal Arctic sea ice. Marine Ecology Progress Series 225, 1–16. Publisher Full Text

- Gasol J.M. & del Giorgio P.A. 2000. Using flow cytometry for counting natural planktonic bacteria and understanding the structure of planktonic bacterial communities. Scientia Marina 64, 197–224. Publisher Full Text

- Gradinger R.R. & Baumann M.E.M. 1991. Distribution of phytoplankton communities in relation to the large-scale hydrographical regime in the Fram Strait. Marine Biology 111, 311–321. Publisher Full Text

- Grasshoff K., Ehrhardt M. & Kremling K. 1999. Methods of seawater analysis, 3rd edn. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley.

- Harrison W.G., Børsheim K.Y., Li W.K.W., Maillet G.L., Pepin P., Sakshaug E., Skogen M.D. & Yeats P.A. 2013. Phytoplankton production and growth regulation in the Subarctic North Atlantic: a comparative study of the Labrador Sea–Labrador/Newfoundland shelves and Barents/Norwegian/Greenland seas and shelves. Progress in Oceanography 114, 26–45. Publisher Full Text

- Hegseth E.N. & Sundfjord A. 2008. Intrusion and blooming of Atlantic phytoplankton species in the High Arctic. Journal of Marine Systems 113–114, 108–119. Publisher Full Text

- Hegseth E.N. & Tverberg V. 2013. Effect of Atlantic Water inflow on timing of the phytoplankton spring bloom in a High Arctic fjord (Kongsfjorden, Svalbard). Journal of Marine Systems 74, 94–105. Publisher Full Text

- Hildebrandt N., Niehoff B. & Sartoris F.J. 2014. Long-term effects of elevated CO2 and temperature on the Arctic calanoid copepods Calanus glacialis and C. hyperboreus. Marine Pollution Bulletin 80, 59–70. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Hilligsøe K.M., Richardson K., Bendtsen J., Sørensen L.L., Nielsen T.G. & Lyngsgaard M.M. 2011. Linking phytoplankton community size composition with temperature, plankton food web structure and sea–air CO2 flux. Deep-Sea Research Part I 58, 826–838. Publisher Full Text

- Hirche H.J., Baumann M.E.M., Kattner G. & Gradinger R. 1991. Plankton distribution and the impact of copepod grazing on primary production in Fram Strait, Greenland Sea. Journal of Marine Systems 2, 477–494. Publisher Full Text

- Hirche H.J. & Kosobokova K.N. 2007. Distribution of Calanus finmarchicus in the northern North Atlantic and Arctic Ocean—expatriation and potential colonization. Deep-Sea Research Part II 54, 2729–2747. Publisher Full Text

- Hop H., Falk-Petersen S., Svendsen H., Kwasniewski S., Pavlov V., Pavlova O. & Søreide J.E. 2006. Physical and biological characteristics of the pelagic system across Fram Strait to Kongsfjorden. Progress in Oceanography 71, 182–231. Publisher Full Text

- Jeffrey S.W. & Vesk M. 1997. Introduction to marine phytoplankton and their pigment signatures. In S.W. Jeffrey et al. (eds.): Phytoplankton pigments in oceanography: guideline to modern methods. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Kahru M., Brotas V., Manzano-Sarabia M. & Mitchell B.G. 2011. Are phytoplankton blooms occurring earlier in the Arctic? Global Change Biology 17, 1733–1739. Publisher Full Text

- Kilias E., Wolf C., Nöthig E.-M., Peeken I. & Metfies K. 2013. Protist distribution in the western Fram Strait in summer 2010 based on 454-pyrosequencing of 18S rDNA. Journal of Phycology 49, 996–1010.

- Kilias E.S., Nöthig E.-M., Wolf C. & Metfies K. 2014. Picoeukaryote plankton composition off west Spitsbergen at the entrance to the Arctic Ocean. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 61, 569–579. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Koszteyn J., Timofeev S., Weslawski J.M. & Malinga B. 1995. Size structure of Themisto abyssorum Boeck and Themisto libellula (Mandt) populations in the European Arctic seas. Polar Biology 15, 85–92. Publisher Full Text

- Kraft A., Bauerfeind E. & Nöthig E.-M. 2011. Amphipod abundance in sediment trap samples at the long-term observatory Hausgarten (Fram Strait, ~79°N/4°E). Variability in species community patterns. Marine Biodiversity 41, 353–364. Publisher Full Text

- Kraft A., Bauerfeind E., Nöthig E.-M. & Bathmann U. 2012. Size structure and life cycle patterns of dominant pelagic amphipods collected as swimmers in sediment traps in the eastern Fram Strait. Journal of Marine Systems 95, 1–15. Publisher Full Text

- Kraft A., Nöthig E.-M., Bauerfeind E., Wildish D.J., Pohle G.W., Bathmann U.V., Beszczynska-Möller A. & Klages M. 2013. First evidence of reproductive success in a southern invader indicates possible community shifts among Arctic zooplankton. Marine Ecology Progress Series 493, 291–296. Publisher Full Text

- Kwasniewski S., Hop H., Falk-Petersen S. & Pedersen G. 2003. Distribution of Calanus species in Kongsfjorden, a glacial fjord in Svalbard. Journal of Plankton Research 25, 1–20. Publisher Full Text

- Lalande C., Bauerfeind E. & Nöthig E.-M. 2011. Downward particulate organic carbon export at high temporal resolution in the eastern Fram Strait: influence of Atlantic Water on flux composition. Marine Ecology Progress Series 440, 127–136. Publisher Full Text

- Lalande C., Bauerfeind E., Nöthig E.-M. & Beszczynska-Möller A. 2013. Impact of a warm anomaly on export fluxes of biogenic matter in the eastern Fram Strait. Progress in Oceanography 109, 70–77. Publisher Full Text

- Lebaron P., Servais P., Agogue H., Courties C. & Joux F. 2001. Does the high nucleic acid content of individual bacterial cells allow us to discriminate between active cells and inactive cells in aquatic systems? Applied and Environmental Microbiology 67, 1775–1782. PubMed Abstract | PubMed Central Full Text | Publisher Full Text

- Li W.K.W., McLaughlin F.A., Lovejoy C. & Carmack E. 2009. Smallest algae thrive as the Arctic Ocean freshens. Science 326, 539. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Margulies M., Egholm M., Altman W.E., Attiya S., Bader J.S., Bemben L.A., Berka J., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z.T., Dewell S.B., Du L., Fierro J.M., Gomes X.V., Godwin B.C., He W., Helgesen S., Ho C.H., Irzyk G.P., Jando S.C., Alenquer M.L.I., Jarvie T.P., Jirage K.B., Kim J.B., Knight J.R., Lanza J.R., Leamon J.H., Lefkowitz S.M., Lei M., Li J., Lohman K.L., Lu H., Makhijani V.B., McDade K.E., McKenna M.P., Myers E.W., Nickerson E., Nobile J.R., Plant R., Puc B.P., Ronan M.T., Roth G.T., Sarkis G.J., Simons J.F., Simpson J.W., Srinivasan M., Tartaro K.R., Tomasz A., Vogt K.A., Volkmer G.A., Wang S.H., Wang Y., Weiner M.P., Yu P.G., Begley R.F. & Rothberg J.M. 2005. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437, 376–380. PubMed Abstract | PubMed Central Full Text

- Maritorena S. & Siegel D.A. 2005. Consistent merging of satellite ocean color data sets using a bio-optical model. Remote Sensing of the Environment 94, 429–440. Publisher Full Text

- Maslanik J.A., Fowler C., Stroeve J., Drobot S., Zwally J., Yi D. & Emery W. 2007. A younger, thinner Arctic ice cover: increased potential for rapid, extensive sea-ice loss. Geophysical Research Letters 34, L24501, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2007GL032043 Publisher Full Text

- Maslanik J.A., Stroeve J., Fowler C. & Emery W. 2011. Distribution and trends in Arctic sea ice age though spring 2011. Geophysical Research Letters 38, L13502, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2011GL047735 Publisher Full Text

- Mebrahtom Kidane Y. 2011. Distribution of unicellular plankton organisms in the ‘AWI Hausgarten’ (79°N/4°E) during summer in relation to a changing Arctic environment. Master’s thesis, University of Bremen.

- Morán X.A.G., López-Urrutia A., Calvo-Díaz A. & Li W.K.W. 2010. Increasing importance of small phytoplankton in a warmer ocean. Global Change Biology 16, 1137–1144. Publisher Full Text

- Mumm N., Auel H., Hanssen H., Hagen W., Richter C. & Hirche H.-J. 1998. Breaking the ice: large-scale distribution of mesozooplankton after a decade of Arctic and transpolar cruises. Polar Biology 20, 189–197. Publisher Full Text

- Oksanen J., Blanchet F.G., Kindt R., Legendre P., O’Hara R.B., Simpson G.L., Solymos P., Stevens M.H.H. & Wagner H. 2011. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 1.17–6.

- Piepenburg D. & Bluhm B.A. 2009. Arctic seafloor life, glasnost and climate change. In G. Hempel & I. Hempel (eds.): Biological studies in polar oceans: exploration of life in icy waters. Pp. 133–142. Wilhelmshaven, Germany: Wirtschaftsverlag Nordwest.

- Piontek J., Sperling M., Nöthig E.-M. & Engel A. 2014. Regulation of bacterioplankton activity in Fram Strait (Arctic Ocean) during early summer: the role of organic matter supply and temperature. Journal of Marine Systems 132, 83–94. Publisher Full Text

- Reigstad M., Carroll J., Slagstad D., Ellingsen I.H. & Wassmann P. 2011. Intra-regional comparison of productivity, carbon flux and ecosystem composition within the northern Barents Sea. Progress in Oceanography 90, 33–46. Publisher Full Text

- Richter C. 1995. Seasonal changes in the vertical distribution of mesozooplankton in the Greenland Sea Gyre (75°N): distribution strategies of calanoid copepods. ICES Journal of Marine Science 52, 533–539. Publisher Full Text

- Robertson B.R. & Button D.K. 1989. Characterizing aquatic bacteria according to population, cell-size, and apparent DNA content by flow-cytometry. Cytometry 10, 70–76. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Saiz E., Calbet A., Isari S., Anto M., Velasco E.M., Almeda R., Movilla J. & Alcaraz M. 2013. Zooplankton distribution and feeding in the Arctic Ocean during a Phaeocystis pouchetii bloom. Deep-Sea Research Part I 72, 17–33. Publisher Full Text

- Servais P., Casamayor E.O., Courties C., Catala P., Parthuisot N. & Lebaron P. 2003. Activity and diversity of bacterial cells with high and low nucleic acid content. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 33, 41–51. Publisher Full Text

- Seuthe L., Töpper B., Reigstad M., Thyrhaug R. & Vaquer-Sunyer R. 2011. Microbial communities and processes in ice-covered Arctic waters of the northwestern Fram Strait (75 to 80°N) during the vernal pre-bloom phase. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 64, 253–266. Publisher Full Text

- Sherr E.B., Sherr B.F. & Longnecker K. 2006. Distribution of bacterial abundance and cell-specific nucleic acid content in the northeast Pacific Ocean. Deep-Sea Research Part I 53, 713–725. Publisher Full Text

- Smedsrud L.H., Sirevaag A., Kloster K., Sorteberg A. & Sandven S. 2011. Recent wind driven high sea ice area export in the Fram Strait contributes to Arctic sea ice decline. The Cryosphere 5, 821–829. Publisher Full Text

- Smedsrud L.H., Sorteberg A. & Kloster K. 2008. Recent and future changes of the Arctic sea-ice cover. Geophysical Research Letters 35, L20503, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/ 2008GL034813 Publisher Full Text

- Smith W.O., Baumann M.E.M., Wilson D.L. & Aletsee L. 1987. Phytoplankton biomass and productivity in the marginal ice zone of the Fram Strait during summer 1984. Journal of Geophysical Research 92, 6777–6786. Publisher Full Text

- Sogin M.L., Morrison H.G., Huber J.A., Mark Welch D., Huse S.M., Neal P.R., Arrieta J.M. & Herndl G.J. 2006. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored “rare biosphere”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America 103, 12115–12120. Publisher Full Text

- Solomon S., Qin D., Manning M., Chen Marquis M., Averyt K.B., Tignor M. & Miller H.L. (eds.) 2007. Climate change 2007. The physical science basis: contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Spreen G., Kaleschke L. & Heygster G. 2008. Sea ice remote sensing using AMSR-E 89 GHz channels. Journal of Geophysical Research—Oceans 113, C02S03, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2005JC003384

- Stoeck T., Bass D., Nebel M., Christen R., Jones M.D.M., Breiner H.W. & Richards T.A. 2010. Multiple marker parallel tag environmental DNA sequencing reveals a highly complex eukaryotic community in marine anoxic water. Molecular Ecology 19, 21–31. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Symon C., Arris L. & Heal B. 2005. Arctic climate impact assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tran S., Bonsang B., Gros V., Peeken I., Sarda-Esteve R., Berhardt A. & Belvisio S. 2013. A survey of carbon monoxide and non-methane hydrocarbons in the Arctic Ocean during summer 2010. Biogeosciences 10, 1909–1935. Publisher Full Text

- Trudnowska E., Szczucka J., Hoppe L., Boehnke R., Hop H. & Blachowiak-Samolyk K. 2012. Multidimensional zooplankton observations on the northern West Spitsbergen Shelf. Journal of Marine Systems 98–99, 18–25. Publisher Full Text

- Unstad K.H. & Tande K.S. 1991. Depth distribution of Calanus finmarchicus and C. glacialis in relation to environmental conditions in the Barents Sea. Polar Research 10, 409–420. Publisher Full Text

- Utermöhl H. 1958. Zur Vervollkommnung der quantitativen Phytoplankton-Methodik. (Improvement of the quantitative phytoplankton methodology.) Stuttgart: International Association of Theoretical and Applied Limnology.

- Wassmann P. 2011. Arctic marine ecosystems in an era of rapid climate change. Progress in Oceanography 90, 1–17. Publisher Full Text

- Wassmann P. & Reigstad M. 2011. Future Arctic Ocean seasonal ice zones and implications for pelagic–benthic coupling. Oceanography 24, 220–231. Publisher Full Text

- Wassmann P.F., Slagstad D. & Ellingsen I.H. 2010. Primary production and climatic variability in the European sector of the Arctic Ocean prior to 2007: preliminary results. Polar Biology 33, 1641–1650. Publisher Full Text

- Weslawski J.M., Kwasniewski S. & Stempniewicz L. 2009. Warming in the Arctic may result in the negative effects of increased biodiversity. Polarforschung 78, 105–108.

- Wolf C., Frickenhaus S., Kilias E.S., Peeken I. & Metfies K. 2013. Regional variability in eukaryotic protist communities in the Amundsen Sea. Antarctic Science 25, 741–751. Publisher Full Text