The green care code: How nature connectedness and simple activities help explain pro-nature conservation behaviours

Опубликована Янв. 1, 2020

Последнее обновление статьи Окт. 17, 2022

Abstract

The biodiversity crisis demands greater engagement in pro-nature conservation behaviours. Research has examined factors which account for general pro-environmental behaviour; that is, behaviour geared to minimizing one's impact on the environment. Yet, a dearth of research exists examining factors that account for pro-nature conservation behaviour specifically—behaviour that directly and actively supports conservation of biodiversity.

This study is the first of its kind to use a validated scale of pro-nature conservation behaviour. Using online data from a United Kingdom population survey of 1,298 adults (16+ years), we examined factors (composed of nine variable-blocks of items) that accounted for pro-nature conservation behaviour.

These were: individual characteristics (demographics, nature connectedness), nature experiences (time spent in nature, engaging with nature through simple activities, indirect engagement with nature), knowledge and attitudes (knowledge/study of nature, valuing and concern for nature) and pro-environmental behaviour.

Together, these explained 70% of the variation in people's actions for nature.

Importantly, in a linear regression examining the relative importance of these variables to the prediction of pro-nature conservation behaviour, time in nature did not emerge as significant.

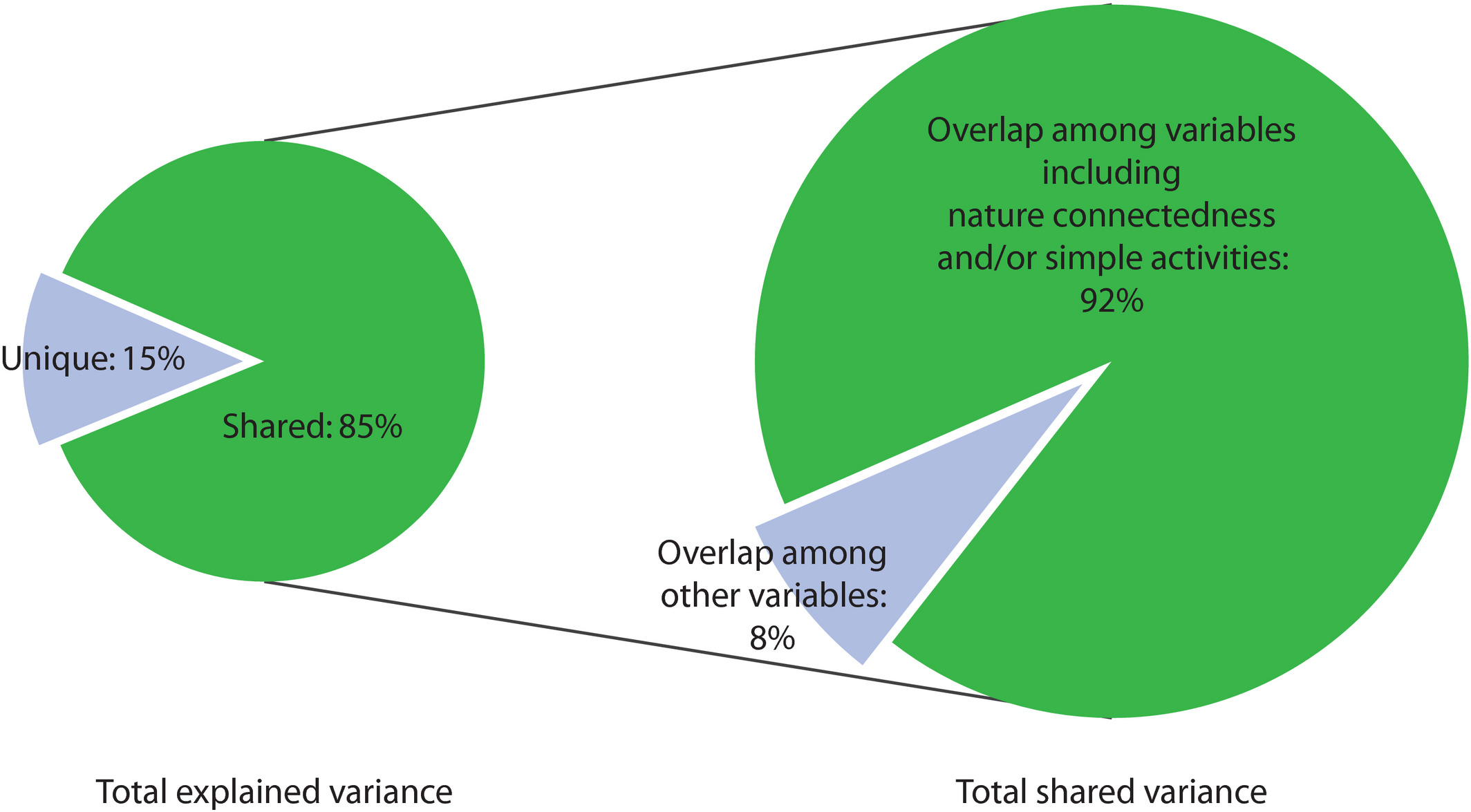

Engaging in simple nature activities (which is related to nature connectedness) emerged as the largest significant contributor to pro-nature conservation behaviour. Commonality analysis revealed that variables worked together, with nature connectedness and engagement in simple activities being involved in the largest portion of explained variance.

Overall, findings from the current study reinforce the critical role that having a close relationship with nature through simple everyday engagement plays in pro-nature conservation behaviour. Policy recommendations are made.

Ключевые слова

Simple activities, nature connectedness, biodiversity, pro-nature conservation behaviour

Global warming (Al-Ghussain, 2018), sea-level rise (Nerem et al., 2018), permafrost degradation (Colucci & Guglielmin, 2019), glacier melting and retreat (Brighenti et al., 2019)—headline news and scientific reports about the disastrous effects of climate change are ubiquitous. However, biodiversity loss is ‘just as catastrophic as climate change’ (Watson, 2019). Biodiversity is a key to the flourishing of all life on Earth—plant and animal, human and other-than-human alike (Diaz, Fargione, Chapin III, & Tilman, 2006; Isbell et al., 2017; Mergeay & Santamaria, 2012; Spicer, 2006), and scientists have long been sounding the alarm over increasing rates of biodiversity loss and the outright extinction of plant and animal species (Wilson & Peter, 1988). Even using extremely conservative assumptions, research clearly identifies an accelerated mass extinction that threatens civilization (Ceballos et al., 2015). To aide nature's recovery, there is an urgent need to understand and promote pro-nature conservation behaviours. However, relatively less attention has been paid to this aspect of sustainability. For example, nearly six times as many Google-hits are returned for a search on ‘climate change’ than for searches for ‘biodiversity loss’ and ‘mass extinction’ combined. Indeed, biodiversity loss and mass extinction have been referred to as ‘the biggest crisis you've probably never heard of’ (Hamiliton, 2018) and ‘an unnoticed apocalypse’ (Goulson, 2019). Nonetheless, awareness is growing as to the seriousness of the problem. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) recently released a report emphasizing how our current era of mass extinction poses an urgent threat to our existence (IPBES, 2019). The report states that approximately a million animal and plant species are currently threatened; an additional approximately 500,000 terrestrial species of animals and plants are labelled ‘dead species walking’ because they are already doomed to extinction due to habitat loss and degradation; and that globally, biodiversity loss and the rate of species extinction have transgressed previously proposed precautionary ‘Planetary Boundaries’. As scientific evidence mounts regarding the seriousness of our current situation (Beaugrand, Edwards, Raybaud, Goberville, & Kirby, 2015; Newbold et al., 2016), newspaper stories on biodiversity loss are becoming increasingly common place (e.g. McKeever, 2016; Watts, 2019). Even the magazine Popular Mechanics recently ran a story under the headline ‘400,000 insect species face extinction’ (Delbert, 2019). Reflecting this growing awareness, socially and demographically representative population surveys of Europeans (European Commission, 2013, 2015, 2018) indicate that while in 2013 only 44% of respondents were familiar with the term ‘biodiversity’, this percentage rose to 60% in 2015, and rose again in the latest survey in 2018 to 70%. While this does not necessarily mean that people better understand the biodiversity concept, conservation stakes, or the complexity of human–nature interrelations, it is encouraging that the percentage of people who acknowledged ‘human responsibility to look after nature’ stood at 96% in 2018, an increase of 20% from 2015. This may indicate a moral shift in the public's perception of the human—nature relationship; that is, moving away from an attitude of ‘mastery over’ nature towards a broad ‘stewardship of nature’ position entailing partnership and participation (see de Groot, Drenthen, & de Groot, 2011). Moreover, while in 2013 only 40% of Europeans reported making active efforts to protect biodiversity, this percentage had risen to 65% in 2018. Clearly, awareness and concern are growing among the general population. It is important to note that while pro-nature conservation behaviours may be seen to overlap with or be embedded within pro-environmental behaviours, these behaviours can be distinguished between. Although research focused on pro-environmental behaviours sometimes includes pro-nature conservation behaviours, factor analysis has evidenced that these behaviours can be distinguished from each other (Martin et al., 2019). While pro-nature conservation behaviours may, at times, be difficult to separately identify due to the diversity of the spectrum of such actions (individual/collective actions, political, economic, etc), one classification method is that of intentionality. Importantly, nature-conservation organizations and scientists acknowledge the differential between pro-nature conservation behaviours and pro-environmental behaviours in published research studies involving leading nature conservation organizations (Hughes, Richardson, & Lumber, 2018; Richardson, Cormack, McRobert, & Underhill, 2016). In general, pro-environmental behaviours are focused on reducing one's carbon footprint and/or minimizing the impact of one's actions on the environment (see reviews by Lange & Dewitte, 2019; Li, Zhao, Ma, Shao, & Zhang, 2019). Behaviours such as recycling, reducing consumption and waste, and taking transit or cycling as modes of transport can be categorized as primarily pro-environmental behaviours. Such actions are vitally important. At the same time, the ecological crises we are now facing also requires individuals to engage in activities that actively and directly support the restoration of the biodiversity of plant and animal species (Ceballos, Ehrlich, & Dirzo, 2017). Such behaviours can be classified as pro-nature conservation behaviours. Examples of pro-nature conservation behaviours include voting for parties/candidates with strong pro-nature conservation policies, volunteering with conservation organizations, installing a bee hotel, planting native plants and leaving undisturbed/unmaintained areas for wildlife (Barbett, Strupple, Sweet, & Richardson, 2019). Although pro-nature conservation behaviours fit within broader definitions (e.g. Steg & Vlek, 2009), as yet, behaviours related to directly supporting habitats for wildlife (i.e. pro-nature conservation) are rarely included in pro-environmental behaviour scales (see summary provided by Gkargkavouzi, Halkos, & Matsiori, 2019, p. 862). Furthermore, as Bamberg and Rees (2015) concluded, the focus of most studies on (and measures of) ‘pro-environmental’ behaviour is geared towards providing ‘information that can be helpful in reducing the negative environmental impact of human activities’ (p. 704). Importantly, nature conservation organizations and conservation scientists acknowledge the differential between pro-nature conservation behaviours and pro-environmental behaviours in published research studies involving leading nature conservation organizations (Hughes et al., 2018; Richardson et al., 2016). Growing awareness of biodiversity notwithstanding, to date, relatively limited attention has been paid to pro-nature conservation behaviours specifically, while a great deal of attention has been paid to general pro-environmental behaviours which mitigate the impact of climate change (e.g. Huynh, 2018; Wynes, 2019; Wynes & Nicholas, 2017). For example, paralleling the imbalanced results of our Google search for the terms ‘climate change’ versus ‘biodiversity’ and ‘mass extinction’, we found that searching for ‘pro-environmental behaviour’ yielded about four times more result-hits than did a search for ‘pro-conservation behaviour’ or ‘pro-nature conservation behaviour’. (Albeit, this could also be a function of conservation behaviour being encompassed within a larger category environmental behaviours.) This lack of focus on biodiversity-specific behaviours has been noted (Prévot, Cheval, Raymond, & Cosquer, 2018). This imbalance is also reflected by the lack of validated psychometric scales for pro-nature conservation behaviours, with the first such scale produced only recently (Barbett, Strupple, Sweet, Schofield, & Richardson, 2020). Research thus far investigating pro-nature conservation behaviour has generally used a selection of ad hoc items. To some extent, this approach can be justified given differing research approaches (e.g. qualitative studies) and contexts (i.e. some behaviours do not make sense in a given context or are not applicable to a particular sample). Understanding individual and contextual factors that influence, account for, and predict both pro-environmental and pro-nature conservation behaviours is vital to informing efforts (individual, organizational, and governmental) geared towards encouraging and boosting engagement in such activities (Stern, 2011; Swim et al., 2011). Much research has been devoted to understanding factors which are associated with or predict pro-environmental behaviours (see reviews Gifford & Nilsson, 2014; Li et al., 2019; Steg & Vlek, 2009; Stern, 2000). Factors including individual traits, experiences in nature, and knowledge and attitudes relating to nature have been examined. For example, socio-demographics such as age, income, and marital status have consistently been associated with one's propensity to engage in environmentally responsible behaviour (see reviews by Gifford & Nilsson, 2014; Li et al., 2019). Consistent evidence has also emerged linking nature connectedness to greater pro-environmental behaviour (see meta-analyses by Mackay & Schmitt, 2019; Whitburn, Linklater, & Abrahamse, 2019), particularly if that attachment to nature was cultivated in childhood through spending free time in nature engaged in unstructured play (Asah, Bengston, Westphal, & Gowan, 2018). Indeed, several researchers have argued that engagement in nature-friendly sustainable behaviours necessarily requires the motivational pre-requisite of feeling connected to nature (Frantz & Mayer, 2014; Kossack & Bogner, 2012; Otto, Kaiser, & Arnold, 2014; Roczen, Kaiser, Bogner, & Wilson, 2014). Given such a causal link of nature connectedness to pro-environmental behaviours (Mackay & Schmitt, 2019) and its dominant role in predicting ecological concern (Otto & Pensini, 2017), there is clear evidence to test the relationship between nature connectedness and pro-nature conservation behaviours. In one of the few studies which have examined this relationship, significant positive correlations were found between nature connectedness and four biodiversity practices (Prévot et al., 2018). Pro-environmental behaviour has been demonstrated to be linked with spending time in nature (Coldwell & Evans, 2017; Larson, Whiting, & Green, 2011; Rosa, Cabicieri Profice, & Collado, 2018; Whitburn, Linklater, & Milfont, 2019), and engaging with nature through simple activities, such as birdwatching or gardening, has been linked to pro-environmental (Sanvichith, 2011) and pro-nature conservation (Cooper, Larson, Dayer, Stedman, & Decker, 2015) behaviours. Simple engagement with nature is also related to nature connectedness (Lumber, Richardson, & Sheffield, 2017; McEwan, Ferguson, Richardson, & Cameron, 2020; Richardson, Hallam, & Lumber, 2015). Engagement with nature through indirect (or vicarious) contact with nature has been shown to play a factor in predicting pro-environmental behaviours. For example, reading books about nature (Mobley, Vagias, & DeWard, 2010), watching nature documentaries (Arendt & Matthes, 2016; Hofman & Hughes, 2018; Holbert, Kwak, & Shah, 2003) or short nature videos (Zelenski, Dopko, & Capaldi, 2015) have all been shown to be positively associated with greater pro-environmental behaviour and/or greater intention to engage in pro-nature conservation behaviours. Additional determinants of environmentally responsible behaviour include having knowledge of nature and holding positive attitudes towards nature such as valuing and being concerned for the environment (Chan, Hon, Chan, & Okumus, 2014; Gungor, Chen, Wu, Zhou, & Shirkey, 2018; Otto & Pensini, 2017; Schneller, Schofield, Frank, Hollister, & Mamuszka, 2015). It is important to note that these are all individual indicators, which have been evidenced across a diverse array of social and cultural contexts (including non-European contexts). A paucity of research exists, however, that investigates factors involved in individual's likelihood to engage in pro-nature conservation behaviour. Thus, in the current study, factors likely to account for and be associated with pro-nature conservation behaviour specifically were examined, using the first validated measure of pro-nature conservation behaviour. The relative importance of such factors was also examined. Data were obtained from a nationally representative survey of adults (16+ years) in the United Kingdom. YouGov is an international public opinion and research data group based in London, United Kingdom that conducts objective demographically representative surveys. YouGov is a member of the British Polling Council, a corporate member of ESOMAR, and is registered with the Information Commissioner; as such, YouGov abides by all of these agencies' respective rules regarding ethical consent of all survey respondents. As per these rules, all respondents provide informed consent to participate in the survey. These rules specify that participants’ rights and well-being are respected via procedures which include complete transparency as to the purpose of the research/survey, how data will be used, and what participation involves; informing participants that their participation is voluntary and they have a right to withdraw at any time. Consent to participate is on this basis.1 The National Trust is a large non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the integrity of the UK's heritage sites and natural places. In 2019, The National Trust commissioned YouGov to conduct a stratified-sample survey across the UK examining adults’ relationship with nature. Aimed at capturing a comprehensive picture, the survey included items pertaining to nature experiences and nature-related activities engaged in, attitudes towards and feelings about nature, concerns about the current state of nature and the environment, and questions regarding engagement in both pro-environmental and pro-nature conservation behaviours. The survey also captured a broad range of demographic statistics, along with aspects of individuals’ physical health and emotional/psychological well-being. This survey was conducted using an online interview administered to members of the YouGov Plc UK panel of 800,000+ individuals who have agreed to take part in surveys. Emails are sent to panellists selected at random from the base sample. The e-mail invites them to take part in a survey and provides a generic survey link. Once a panel member clicks on the link, they are sent to the survey that they are most required for, according to the sample definition and quotas—in this case, a representative sample of the adult population. Invitations to surveys do not expire and respondents can be sent to any available survey. The responding sample is weighted to the profile of the sample definition to provide a representative reporting sample, and is weighted to social grade using ONS data. The profile is normally derived from census data or, if not available from the census, from industry-accepted data. Fieldwork was undertaken between 29th and 30th July 2019. The figures have been weighted and are representative of all GB adults in terms of age (16+), gender, social class and education.2 The original survey sample consisted of 2,096 respondents; of these responses, 798 were removed for either incomplete responses to the pro-nature conservation behaviour measure or if respondents chose the ‘don't know’ option. Thus, our final sample size for analysis was 1,298. (Importantly, there was still a wide range of scores on the pro-nature conservation behaviour measure—from 8 to 55.) Gender was nearly evenly split between males and female; ages ranged from 16 to 55+, with 59% of respondents between the ages of 25 and 54 years, and 41% of respondents over the of 55. Over half (61%) of our sample came from a higher (vs. lower) socio-economic grade; most (60%) respondents had a life partner. (see Table 1 for detailed descriptives.) TABLE 1. Demographic details Demographic % of sample Gender Male 47.2% Female 52.8% Age 16–24 8.1% 25–39 25.4% 40–54 25.6% 55+ 41.0% Socio-economic grade ABC1 60.9% C2DE 39.1% Life partner Have a partner 59.8% Do not have a partner 40.2% The YouGov/National Trust survey employed the recently developed short form of the Pro-Nature Conservation Behaviour Scale (ProCoBS; Barbett et al., 2020). This 8-item measure assesses active behaviours that specifically support the conservation of biodiversity in two areas: civil actions and garden-related behaviours. Items include the following: ‘I get in touch with local authorities on nature conservation issues’ and ‘I plant pollinator-friendly plants (i.e. ones that are good for bees and other insects)’. The scale was originally validated on participants from the UK (α = 0.83; α in the current study = 0.85). Items are summed for a composite score. As introduced above, prior research has evidenced several broad factors which are associated with pro-environmental behaviours. Thus, items from the YouGov/National Trust that were most relevant to these factors were included as a starting point to examining predictors of pro-nature conservation behaviours. These items were then categorized into blocks of variables within the factors as follows. Factor 1—individual characteristics—was composed of two variable-blocks: (a) demographics and (b) nature connectedness. Factor 2—nature experiences—was composed of three variable-blocks: (a) time spent in nature, (b) engagement with nature through simple activities, and (c) indirect engagement with nature. Factor 3—knowledge and attitudes—also consisted of three variable-blocks: (a) knowledge and study of nature, (b) valuing nature, and (c) concern for nature. Given that pro-environmental behaviours are distinct from pro-nature conservation behaviours (Martin et al., 2019), a fourth factor was also included consisting of one variable-block of items regarding pro-environmental behaviours. Next, a series of analyses were run regressing pro-nature conservation behaviour on each variable-block to determine which individual items within each block emerged as significant predictors of pro-nature conservation behaviour. The emergent blocks of items are described below. (See also Table 2 which presents the complete list and wording of all items originally selected, along with their response scales. Detailed linear regression statistics for each variable-block are also included, along with standardized beta values indicating which items emerged as significant and, thus, were included in the finalized blocks for subsequent analysis.) TABLE 2. Block items, regression analyses predicting pro-nature conservation behaviour Variable-blocks, potential items, regression statistics Response scale β, p Factor 1: Individual characteristics Block 1: Demographics F(4, 1,287) = 11.91, R = 0.19, R2 = 0.04, Adj. R2 = 0.03, p < 0.001 *D1. gender Male or female β = 0.089, p = 0.001 *D2. age 16–24, 25–39, 40–54, 55+ β = 0.146, p < 0.001 *D3. socio-economic grade High: ABC1 or low: C2DE β = 0.075, p = 0.007 NID4. life-partner status Yes or no β = −0.048, p = 0.090 Block 2. Nature connectedness F(1, 1,250) = 447.39, R = 0.51, R2 = 0.26, Adj. R2 = 0.26, p < 0.001 *NC1. Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale Choose which diagram of seven best depicts β = 0.513, p < 0.001 Factor 2: Nature experience Block 3. Time in nature F(1, 1,270) = 433.83, R = 0.51, R2 = 0.26, Adj. R2 = 0.25, p < 0.001 *PTN1. In an average week, how many days do you spend more than 1 hr in nature 1 = ‘None’ to 5 = ‘Every day, 7 days’ β = 0.505, p < 0.001 Block 4. Engagement with nature through simple activities F(11, 1,249) = 136.90, R = 0.74, R2 = 0.55, Adj. R2 = 0.54, p < 0.001 NICNSA1. Look at natural scenery from indoors or while on journeys 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.012, p = 0.605 NICNSA2. Sit or relax in a garden 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.033, p = 0.146 *CNSA3. Watch wildlife (e.g. bird watching) 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.174, p < 0.001 *CNSA4. Listen to bird song 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.107, p < 0.001 *CNSA5. Smelt wild flowers 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.192, p < 0.001 *CNSA6. Taken a photo/drawn or painted a picture of a natural views, plant, flower or animal 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.127, p < 0.001 *CNSA7. Collected shells or pebbles on the beach 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.093, p < 0.001 *CNSA8. Take time to notice butterflies and/or bees 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.203, p < 0.001 NICNSA9. Stopped to look at the moon and/or stars in the sky 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.047, p = 0.064 *CNSA10. Watched the sun rise 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.113, p < 0.001 *CNSA11. Watched clouds 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = −0.077, p = 0.003 Block 5. Indirect engagement with nature F(3, 1,280) = 322.98, R = 0.66, R2 = 0.43, Adj. R2 = 0.43, p < 0.001 NIICN1. Watch or listen to nature programmes on the TV or radio. 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.046, p = 0.071 *ICN2. Look at books, photos or websites about the natural world 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.328, p < 0.001 *ICN3. Talk about nature or wildlife with family or friends (online or face-to-face) 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.376, p < 0.001 Factor 3: Knowledge and attitudes Block 6. Knowledge and study of nature F(2, 1,283) = 380.34, R = 0.61, R2 = 0.37, Adj. R2 = 0.37, p < 0.001 *KSN1. I know a lot about nature and wildlife (such as birds, animals, insects, etc.) 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’ β = 0.364, p < 0.001 *KSN2. Studied nature with a microscope or binoculars 1 = ‘Never’ to 4 = ‘Often’ β = 0.375, p < 0.001 Block 7. Valuing nature F(6, 1,243) = 88.76, R = 0.55, R2 = 0.30, Adj. R2 = 0.30, p < 0.001 *VN1. How would you feel if these animals no longer existed? 1 = ‘Very happy’ to 5 = ‘Very unhappy’ β = 0.055, p = 0.032 *VN2. Ensuring people have jobs in the UK today is more important than protecting nature and wildlife for the future. (reverse coded) 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’ β = 0.125, p < 0.001 *VN3. It is important that there are strong laws to protect nature in the UK 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’ β = 0.189, p < 0.001 *VN4. I feel more comfortable in the city than in the countryside (reverse coded) 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘Strongly agree’ β = 0.076, p = 0.002 *VN5. I get a good deal of pleasure from my garden 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘Strongly agree’ β = 0.369, p < 0.001 NIVN6. Our coast is a national treasure 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘Strongly agree’ β = 0.018, p = 0.491 Block 8. Concern for nature F(2, 1,254) = 230.99, R = 0.51, R2 = 0.27, Adj. R2 = 0.27, p < 0.001 *CN1. How concerned or unconcerned are you about the decline in wild life in the UK (e.g. birds, animals, insects, etc.) 1 = ‘Not at all concerned’ to 4 = ‘Very concerned’ β = 0.447, p < 0.001 *CN2. I am more concerned about nature and wildlife than I was a year ago 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’ β = 0.135, p < 0.001 Factor 4: Pro-environmental behaviour Block 9. Pro-environmental behaviour F(6, 351) = 24.92, R = 0.55, R2 = 0.30, Adj. R2 = 0.29, p < 0.001 *PEB1. Reduced the number of flights I take 1 = ‘I have not done this’ to 2 = ‘I have done this’ β = 0.211, p < 0.001 NIPEB2. Walked, cycled or used public transit (such as trains, bus, etc.) instead of a car 1 = ‘I have not done this’ to 2 = ‘I have done this’ β = 0.094, p = 0.060 *PEB3. Reduced the amount of meat I eat 1 = ‘I have not done this’ to 2 = ‘I have done this’ β = 0.173, p = 0.001 NIPEB4. Used reusable water bottles/coffee cups rather than disposable ones 1 = ‘I have not done this’ to 2 = ‘I have done this’ β = 0.067, p = 0.168 NIPEB5. Worn warmer clothes instead of turning on/up the central heating 1 = ‘I have not done this’ to 2 = ‘I have done this’ β = −0.068, p = 0.174 *PEB6. Chosen to buy local food based on food miles 1 = ‘I have not done this’ to 2 = ‘I have done this’ β = 0.250, p < 0.001 Three items were included in this variable-block: gender, age, and socio-economic grade. The Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale (INS; Schultz, 2001) was selected from the survey items to measure nature connectedness as it taps into less experiential aspects of connection compared to other scales, allowing the impact of the engagement of simple activities to be assessed. The INS is widely used as an assessment of nature connectedness. The INS comprises a single item which asks the respondent to select one of seven diagrams that best describes their relationship with the natural environment. Diagrams depict increasing degrees of overlap between a circle labelled ‘Self’ and a circle labelled ‘Nature’. This variable-block consisted of one item: ‘In an average week, how many days do you spend more than 1 hr in nature (such as garden, park, etc.’). Eight items describing a selection of common, simple nature-related experiences, informed by the Biophilic Values (Kellert, 1993), that people might have engaged in over the past year were included in this variable-block. Some activities were more passive (e.g. ‘watching wildlife’, ‘watched the sun rise’), while others were more active reflecting greater engagement with nature (e.g. ‘collected shells or pebbles’, ‘taken a photo of or draw/paint a picture of a natural view, plant, flower or animal’). Activities involving different senses and different aspects of nature were included (e.g. ‘listening to bird song’, ‘smelt wild flowers’, ‘noticed butterflies and/or bees’). All items constituted some degree of direct exposure to live nature. Two items captured indirect engagement with nature in the past year (i.e. ‘watching/listening to nature programmes on TV or radio’, ‘looking at books, photos, or websites about the natural world’, ‘talking about nature or wildlife with others’). These items were inspired by research of Soga, Gaston, Yamaura, Kurisu, and Hanaki (2016) who evidenced that both direct and indirect (or vicarious) experiences with nature predict children's propensity to preserve biodiversity. Two items were included in this block, one assessing knowledge (i.e. ‘I know a lot about nature and wildlife …’) and one assessing a behavioural aspect of studying nature (‘Studied nature with a microscope or binoculars’.). This block's five items captured both affective and cognitive facets of valuing nature. Items referring to feeling comfortable in nature (i.e. ‘I feel more comfortable in the city than countryside’ [reverse coded]) and gaining pleasure from nature (i.e. ‘I get a good deal of pleasure from my garden’) reflect valuing nature for the benefits it provides to one's emotions. Other items reflect a broader valuing of nature more for its own right (e.g. ‘It is important that there are strong laws to protect nature in the UK’.). Items in this block were based on their similarity to value-based items in existing scales assessing environmental attitudes (e.g. Milfont & Duckitt, 2010). Two items explicitly addressed how concerned respondents were about nature and wildlife (e.g. ‘How concerned or unconcerned are you about the decline in wildlife in the UK’, ‘I am more concerned about nature and wildlife than I was a year ago’). As indicated in Table 2, three items were included in this variable-block of items assessing pro-environmental behaviours. Items in this block were drawn from a variety of existing measures assessing pro-environmental behaviours (e.g. Markle, 2013) and recommendations for reducing one's impact on the environment (e.g. Holth, 2017; Wynes & Nicholas, 2017). Hierarchical linear multiple regression (HLMR) was then used as it is designed for use in theory-driven analyses (Aron & Aron, 1999; Cohen, 2001), such as the current study's approach. An HLMR analytic methodology focuses on the change in predictability associated with variables (or blocks of variables) entered into the equation later in the analysis beyond that contributed by variables entered earlier in the analysis. Nine blocks of variables (described above) were entered into the regression equation predicting pro-nature conservation behaviour. Two main criteria that Petrocelli (2003) outlined as of importance when using hierarchical regression are as follows: (a) grounding the selection of predictor variables and their specific order of entry in sound theoretical basis and (b) ensuring that causal variables are entered into the analysis before their effects (see also Cohen & Cohen, 1983). These criteria are further addressed below in an expanded explanation of each variable-block and the order in which they were entered into the hierarchical regression. Following recommendations to enter more static variables before entering relatively more dynamic variables in later blocks (Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Petrocelli, 2003), individual characteristics were entered first. General demographics were entered as Block 1 of our equation. Nature connectedness has been described as a trait or individual difference characteristic (Capaldi, Dopko, & Zelenski, 2014; Di Fabio & Rosen, 2019; Howell & Passmore, 2013; Nisbet, Zelenski, & Grandpierre, 2019). Thus, nature connectedness was categorized as a static variable and entered in Block 2 of the equation. The rationale for including Nature Connectedness as Block 2 prior to other variables also relates to causal priority. Previous research has demonstrated that nature connectedness is predictive of spending more time in nature engaged in a variety of activities (Asah, Bengston, & Westphal, 2012; Martin et al., 2019; Mayer & Frantz, 2004; Nisbet, Zelenski, & Murphy, 2009; Tam, 2013), of greater valuing and concern for nature (Frantz & Mayer, 2014), and of greater levels of both pro-environmental (see meta-analysis by Mackay & Schmitt, 2019; see also Geng, Xu, Ye, Zhou, & Zhou, 2015; Hinds & Sparks, 2008; Kals, Schumaker, & Montada, 1999; Otto & Pensini, 2017) and pro-nature conservation (Hughes et al., 2018; Richardson et al., 2016) behaviours. Moreover as noted in the introduction, nature connectedness is viewed by many researchers as a necessary pre-requisite to engagement in nature-friendly behaviours. As the most general aspect of nature experiences, time in nature was entered as Block 3. People spend their time in nature in many different ways. Thus, for Block 4, items describing a variety of common simple nature-related activities that involve direct contact with nature were entered. While direct contact with nature has been shown to be more powerful in its beneficial impact, indirect contact with nature has also been shown to promote knowledge and caring for nature (Hofman & Hughes, 2018; Howell, 2014; Jacobsen, 2011; Janpol & Dilts, 2016). Additionally, people often supplement their time in nature by engaging with nature vicariously, such as by reading or talking about nature. Thus, variables describing such indirect engagement with nature were next entered as Block 5 in the regression equation. Diverse avenues of research support casual pathways from contact with nature to enhanced knowledge and study of nature, greater valuing of and concern for nature, and ultimately to increased levels of pro-nature behaviour. For example, across the planet, indigenous peoples for whom affiliating with nature is deeply embedded in their cultural stories and daily life, have detailed, extensive and accurate knowledge of their natural environment (e.g. Bohensky, Butler, & Davies, 2013; Davis, 2009; Nelson, 1983; Robbins, 2018). In America and Norway, adults pursuing environmental careers report having spent more time in nature in their past compared to adults pursuing non-nature-based careers (Chawla, 1999; James, Robert, & Carin, 2010). These nature-career adults also credit their interest in nature as stemming from regularly making contact with nature through a variety of simple direct and indirect activities. Evidence from social psychology research suggests that direct experiences foster enhance attitude-behaviour consistency (Fazio & Zanna, 1981). In line with this, Coldwell and Evans (2017) found that people who spend more time in nature tend to have higher levels of biodiversity knowledge, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviours. Collado, Staats, and Corraliza (2013) proposed that, ‘People who experience benefits from being in nature may want to preserve the places where they obtain these benefits and may be more willing to carry out ecological behaviours’ (p. 37). Several studies support this supposition, empirically demonstrating that enjoyable physical, experiential contact with nature cultivates a positive attitude towards, and valuing of, nature resulting in a deepening concern for nature—all factors which encourage people to actively care for the environment (Bendt, Barthel, & Colding, 2013; Collado et al., 2013; Kane & Kane, 2011; Teisl & O'Brien, 2003; Zaradic, Pergams, & Kareiva, 2009; see also Soga & Gaston, 2016). Gifford and Nilsson (2014) argued that, ‘One is unlikely to knowingly be concerned about the environment or deliberately act in pro-environmental ways if one knows nothing about the problem or potential positive actions’. (p. 142). As noted in the introduction, empirical support for knowledge of nature leading to pro-environmental behaviours has been evidenced in several studies (e.g. Chan et al., 2014; Gungor et al., 2018; Otto & Pensini, 2017; Schneller et al., 2015). Thus, items for knowledge and study of nature were entered next, followed by valuing nature, and then concern for nature as Blocks 6, 7, and 8 in the regression equation. Given that pro-environmental and pro-nature conservation behaviours are distinct, items pertaining to pro-environmental behaviours were entered as the last block in the regression equation. All assumptions for linear regression were met (i.e. multicollinearity, independent errors, heteroscedasticity, and normality of residuals: Durbin–Watson = 2.03, VIF: 1.14–3.00; tolerance: 0.33–0.87, highest r = 0.65; Breusch–Pagan: p = 0.859; Koenker: p = 0.769; see also Table 3). Sample size provided adequate power for the number of variables entered (sample size estimated for small effect size, α = 0.05, power = 0.80: suggested N = 1,195). TABLE 3. Hierarchical linear regression—predicting pro-nature conservation behaviour Steps/blocks entered R R 2 Adj. R2 SE ΔR2 ΔF df1 df2 p Block 1. Demographics 0.22 0.05 0.04 10.98 0.05 6.63 3 404 <0.001 Block 2. Nature connectedness 0.57 0.33 0.32 9.25 0.28 166.71 1 403 <0.001 Block 3. Time in nature 0.61 0.37 0.36 8.95 0.04 28.02 1 402 <0.001 Block 4. Engaging with nature through simple activities 0.77 0.59 0.58 7.31 0.22 26.19 8 394 <0.001 Block 5. Indirect engagement with nature 0.79 0.63 0.62 6.96 0.04 21.24 2 392 <0.001 Block 6. Knowledge and study of nature 0.80 0.64 0.63 6.85 0.01 7.54 2 390 0.001 Block 7. Valuing nature 0.82 0.67 0.65 6.65 0.03 5.79 5 385 <0.001 Block 8. Concern for nature 0.82 0.68 0.66 6.54 0.01 7.12 2 383 0.001 Block 9. Pro-environmental behaviour 0.84 0.70 0.68 6.35 0.02 8.77 3 380 <0.001 The regression had nine blocks, with each block consisting of one variable-block of items (as noted above) added to the equation. The full model (wherein all nine variable-blocks were included) explained 70% (R2 = 0.70, Adj. R2 = 0.68) of the variance in pro-nature conservation behaviour. As presented in Table 3, the first four blocks (demographics, nature connectedness, time in nature, and engagement with nature through simple activities) accounted for the bulk of variance explained in pro-nature conservation behaviour (R2 = 0.59, Adj. R2 = 0.58), with each block making a significant contribution. Demographics (Block 1) accounted for 5% of the variance in pro-nature conservation behaviour. Nature connectedness (Block 2) accounted for an additional 28% of variance above demographics. Time in nature (Block 3) accounted for a further 4%, and engagement with nature through simple activities (Block 4) accounted for an additional 22% of variance in pro-nature conservation behaviour over and above the first three variable-blocks (i.e. demographics, nature connectedness, and preference for time in nature). Combined, indirect engagement with nature, knowledge/study of nature, valuing nature, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviours (Blocks 5–9) accounted for the remaining 11% of variance in pro-nature conservation behaviour, with each block making a significant contribution (between 1% and 4%) over and above previously entered blocks (i.e. demographics, nature connectedness, time in nature, contact with nature through simple activities). The theoretically based hierarchical regression was followed by a predictive linear regression. To do so, all individual items were first standardized. For those variable-blocks composed of more than one item, a composite measure was created (as per Passmore & Holder, 2017; Zelenski & Nisbet, 2014) by computing the mean of the standardized items comprising the block. Demographics were not included in this analysis. Linear regression using the resultant composite measures (entered into the equation simultaneously) revealed that, when controlling for/holding other variables constant, nature connectedness, engagement with nature through simple activities, indirect engagement with nature, knowledge/study of nature, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviour all emerged as significant predictors of pro-nature conservation behaviour (respective ps < 0.001, < 0.001, < 0.001, 0.001, 0.006, < 0.001). Time spent in nature and valuing nature did not emerge as significant predictors (ps = 0.099, 0.351), with standardized beta values between one-sixth to one-quarter as small as those for the remaining predictors (see Tables 4 and 5). TABLE 4. Linear regression—composite measures predicting pro-nature conservation behaviour Measure b SE β p *Nature connectedness 1.52 0.42 0.13 <0.001 NITime in nature 0.67 0.41 0.06 0.099 *Engagement with nature through simple activities 4.15 0.77 0.26 <0.001 *Indirect engagement with nature 2.25 0.58 0.18 <0.001 *Knowledge and study of nature 1.83 0.53 0.13 0.001 NIValuing nature 0.63 0.68 0.04 0.351 *Concern for nature 1.25 0.45 0.10 0.006 *Pro-environmental behaviour 2.78 0.51 0.19 <0.001 F(8, 399) = 105.28, R = 0.82, R2 = 0.68, Adj. R2 = 0.67, p < 0.001 TABLE 5. Reliability statistic, correlations (simple and disattenuateda) for composite measures Cronbach's α ProCoBS Simple activities Indirect engmnt Knowlg and study Valuing Concern ProCoBS 0.85 — Simple activities 0.85 Obs: 0.72 Cor: 0.85 — Indirect engagement 0.75 Obs: 0.66 Cor: 0.82 Obs: 0.71 Cor: 0.89 — Knowledge and study 0.53 Obs: 0.61 Cor: 0.91 Obs: 0.63 Cor: 0.93 Obs: 0.62 Cor: 0.98 — Valuing 0.42 Obs: 0.49 Cor: 0.83 Obs: 0.49 Cor: 0.82 Obs: 0.47 Cor: 0.84 Obs: 0.39 Cor: 0.83 — Concern 0.57 Obs: 0.49 Cor: 0.70 Obs: 0.41 Cor: 0.59 Obs: 0.45 Cor: 0.69 Obs: 0.33 Cor: 0.60 Obs: 0.51 Cor: 1.00 — Pro-environ. beh. 0.71 Obs: 0.56 Cor: 0.72 Obs: 0.48 Cor: 0.62 Obs: 0.47 Cor: 0.64 Obs: 0.36 Cor: 0.58 Obs: 0.43 Cor: 0.79 Obs: 0.50 Cor: 0.79 The current study also sought to better understand the overlap between our factors of nature connectedness, experiences with nature, knowledge and attitudes about nature, and pro-environmental behaviours in the prediction of pro-nature conservation behaviour. To explore this, a commonality analysis (Nimon, 2010) was conducted. Commonality analysis provides a more thorough understanding of regression analysis because it partitions the explained variance based on the unique and nonunique contributions of each variable (Nimon, 2010; Nimon, Lewis, Kane, & Haynes, 2008; Ray-Mukherjee et al., 2014). Unique effects refer to the portion of variance that is unique to each particular variable. Non-unique effects (i.e. common or shared effects) identify the portion of variance that is common to or shared with every other variable in the regression. Thus, commonality analysis provides a more complete picture of the relationship between predictor variables and dependent variables. As Siebold and McPhee (1979) noted, the usefulness of research findings ‘depend not only on establishing that a relationship exists among predictors and the criterion, but also upon determining the extent to which those independent variables, singly and in all combinations, share variance with the dependent variable’ (p. 355) [emphasis added]. Time spent in nature and valuing nature were not included in the commonality analysis, as these variables did not emerge as significant predictors of pro-nature conservation behaviour. We utilized Nimon's SPSS syntax to conduct the analysis (K. Nimon, pers. comm.; see also Nimon, 2010) on the six significant predictor variables (i.e. nature connectedness, engagement with nature through nature activities, indirect engagement with nature, knowledge/study of nature, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviour). Only cases with complete data (i.e. no missing items for any variable) were used as per the requirements for commonality analysis using this syntax. Individual variables each accounted for only 1%–4% of the explained variance in pro-nature conservation behaviour. Combined, unique contributions of the individual variables accounted for 15% of explained variance. The remaining 85% of explained variance was attributable to overlap among the individual variables (Table 6). TABLE 6. Linear regression—simple activities predicting nature connectedness Simple activity b SE β p Watch wildlife 0.17 0.03 0.18 <0.001 Listen to birdsong 0.10 0.03 0.10 <0.001 Smell wild flowers 0.17 0.03 0.17 <0.001 Take a photo of or draw nature 0.04 0.02 0.04 0.056 Collect shells or pebbles on beach −0.03 0.02 −0.03 0.225 Notice butterflies or bees 0.10 0.03 0.09 0.001 Watch the sun rise 0.05 0.03 0.05 0.033 Watch clouds 0.01 0.03 0.01 0.699 Look at natural scenery 0.09 0.03 0.07 0.003 Sit or relax in garden 0.10 0.03 0.09 <0.001 Look at moon or stars −0.03 0.03 −0.02 0.354 F(11, 1837) = 76.66, R = 0.56, R2 = 0.32, Adj. R2 = 0.31, p < 0.001 That nature connectedness has been proposed as a necessary pre-requisite for engagement in nature-friendly sustainable behaviours (Frantz & Mayer, 2014; Kossack & Bogner, 2012; Otto et al., 2014; Otto & Pensini, 2017; Roczen et al., 2014) suggests that nature connectedness contributes to pro-nature conservation behaviour not only through its unique contributions but also in concert with other variables. At the same time, engagement with simple activities emerged as the largest predictor of pro-nature conservation in our linear regression. To further investigate these two aspects, the portion of variance attributable to overlap was parsed into overlap among variables including nature connectedness and/or simple activities and overlap among variables not including nature connectedness and/or simple activities. As depicted in Figure 1, 92% of the overlap involved variance shared among nature connectedness and/or simple activities in combination with the other variables; 8% of the overlap involved variance shared among variables of indirect engagement with nature, knowledge/study of nature, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviour. FIGURE 1 Commonality analysis for explained variance in pro-nature conservation behaviour The loss of biodiversity and mass extinction crises occurring currently threatens life as we know it—human and greater-than-human. Consensus of the scientific community clearly asserts that the unprecedented acceleration of these ecological crises is human-driven (Ceballos et al., 2015). Wider engagement with pro-nature behaviours needs to be encouraged, actions geared not only towards reducing our impact on the earth (i.e. pro-environmental behaviours) but also actions specifically geared to directly impacting and supporting restoration of biodiversity (i.e. pro-nature conservation behaviours) which previous research suggests are distinct (Martin et al., 2019). To do so, factors that contribute to individuals’ proclivity to engage in pro-nature conservation behaviours need to be understood. To that end, in the current study using national survey data from households in the United Kingdom, factors which account for pro-nature conservation behaviour were examined. This study is the first of its kind to use a validated measure of pro-nature conservation behaviour. Items for inclusion in this study were selected from the larger collection of survey items based on theoretical relevance and prior research examining factors which account for pro-environmental behaviour. These items were then categorized into four factors (i.e. individual characteristics, nature experiences, knowledge and attitude, and pro-environmental behaviour) comprising nine variable-blocks (i.e. demographics, nature connectedness, engagement with nature through simple activities, indirect engagement with nature, knowledge and study of nature, valuing nature, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviour). To hone the item list, pro-nature conservation was regressed on each block of items, selecting only those variables which emerged as significant predictors. A pattern emerged across the blocks of items with regard to which items were removed as non-significant predictors of pro-nature conservation behaviour. Within the variable-blocks of direct engagement with nature through simple activities, indirect engagement with nature, and pro-environmental behaviours, it was the more active items that were retained as they emerged as significantly associated with engagement in behaviours that actively and directly support conservation of biodiversity. For example, within the simple activities variable-block, the highly passive activities of looking at nature scenery from indoors or a car/train and merely relaxing in a garden were removed as non-significant, as was the activity of looking at the night sky (moon, stars). Significant items retained in this block involved activities that not only engaged a person more intimately with nature through different senses (such as smelling wildflowers, collecting shells, listening to bird songs, noticing or watching bees) but also accentuated awareness of the diversity of the natural world around us. Aspects of proximity to aspects of nature and intention of the behaviour (e.g. purposefully seeking out biodiversity) may also have been at play. Within the variable-block denoting indirect engagement with nature, the more passive activity of merely watching or listening to nature programmes on TV or radio was removed as a non-significant predictor of pro-nature conservation behaviour, while the more (intellectually, socially and effortful) active items of looking at nature-related books or websites and making nature the topic of conversation with others were retained. Again, these activities reflect greater personal and purposeful involvement. As noted above, differing intentions for engaging in these activities may also be an active agent at play. For example, perhaps engaging in the more passive activities of watching or listening to nature programmes is driven by more by intentions related to distraction and relaxation, than by intentions to acquire greater intimacy with or share experiences of nature. Within the pro-environmental behaviours variable-block, it was, again, the activities that required greater effort or involved greater impact on one's lifestyle (reducing the number of flights, eating less meat, choosing local food) that emerged as significant predictors of pro-nature conservation behaviours, while items activities or choices that required less effort and are easier (and more common) to implement were dropped as non-significant (i.e. taking public transit or cycling, using reusable water bottles/coffee cups rather than disposable ones, throwing on warmer clothes rather than turning up the thermostat). Using the resultant, refined variable-blocks of items, an hierarchical regression was next run, entering blocks of variables into the equation in causal order based on theory and prior research findings. That is, individual characteristics (demographics, nature connectedness) were entered first, followed by nature experiences (time spent, simple activities, indirect engagement), knowledge and attitude (knowledge, valuing, concern) and lastly pro-environmental behaviour. The full model including all nine blocks comprising the four factors accounted for 70% of the variation in people's pro-nature conservation behaviour. Each of the nine variable-blocks accounted for an additional significant amount of variance beyond blocks entered prior to. However, blocks which contributed the most were nature connectedness (Block 2) and simple activities (Block 4), accounting for an additional 28% and 22%, respectively, of variance beyond that accounted for by blocks entered prior to. The remaining variable-blocks accounted for the remaining 15% of variance: time spent in nature (4%), indirect engagement with nature (4%), knowledge/study of nature (1%), valuing nature (3%), concern for nature (1%) and pro-environmental behaviour (2%). While order of entry into the regression most certainly influences the amount of additional variance each block does (indeed, can) account for, order of entry into the regression was not the sole determinant of amount of additional variance accounted for. For example, simple activities accounted for 22% of additional variance in pro-nature conservation behaviours, even though simple activities were entered as Block 4, after time spent in nature (Block 3), which accounted for only 4% of additional variance. To further explore these results, and to help determine the relative predictive value of each of these determinants of pro-nature conservation behaviour, composite measures of each variable-block of items were created (with the exception of demographics) and entered simultaneously into a regression predicting pro-nature conservation behaviour. When holding all other variables constant, time spent in nature did not emerge as a significant predictor. This finding is important to emphasize, as it suggests that merely spending time in nature per se is not enough by itself to prompt individuals to engage in active nature-friendly behaviour which directly impacts ecological conservation and restoration of biodiversity. Rather, it is how that time is spent that is a key influential factor in predicting pro-nature conservation behaviour. Indeed, simple activities emerged with the largest standardized beta value of all the significant predictors in the equation (i.e. nature connectedness, indirect engagement with nature, knowledge/study of nature, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviour). The close relationship between the simple activities and nature connectedness should be recognized. The simple activities operationalize the pathways to nature connectedness (Lumber et al., 2017) and are similar to the ‘good things in nature’, in that both are types of engagement that lead to nature connectedness (McEwan et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2015). Therefore, these simple activities can also be seen as indicators of nature connectedness, especially as the chosen nature connectedness scale does not tap into engagement with nature. Truly engaging and connecting with nature through intimate, yet simple, activities involving one's physical senses of sight, sound, smell, and touch appears to be a key pathway to moving people towards greater engagement in conservation-friendly behaviours. This is in line with previous research demonstrating that time spent in nature as a child engaged in unstructured active play—interacting with nature's 'loose parts’ (e.g. sticks, leaves, pebbles, etc.)—is a key to engaging in pro-environmental behaviour as an adult (e.g. Asah et al., 2018; Chawla, 1999; James et al., 2010). Findings from the current study regarding the importance of how one spends their time in nature also parallels research results, noted previously, evidencing that experiential contact with nature tends to result in a deep concern for nature, influencing people to actively care for the environment (Bendt et al., 2013; Collado et al., 2013; Kane & Kane, 2011; Teisl & O'Brien, 2003; Zaradic et al., 2009). Furthermore, Cosquer, Raymond, and Prevot-Julliard (2012) found that repeated simple engagement with everyday nature (i.e. noticing and counting butterflies in one's own garden) shifted how participants viewed themselves in relation to this natural environment, which acted as a catalyst for several of these participants to begin engaging in gardening practices specifically geared to enhancing biodiversity. Sharing the experience of simple nature activities with others—even indirectly through talking about the activity with others—may have a synergistic effect on boosting people's pro-nature conservation behaviour, given that talking with friends and family about nature emerged in our study as a significant predictor of pro-nature conservation behaviour, even when considering nature connectedness. While this supposition needs to be explored through future research, research literature in the area of meaning in life suggests that sharing with others (via conversations about) what makes one's life meaningful further enhances the meaning that one derives from these experiences (e.g. Steger, Shim, Barenz, & Shin, 2014). A similar principle may be at play here: conversing about engaging in simple nature activities may further enhance one's nature connectedness, thereby further boosting one's proclivity to engage in pro-nature conservation behaviour. Surprisingly, valuing nature did not emerge as a significant predictor of pro-nature conservation behaviour when all other variables were controlled for. This may be due to a suppression effect of the other variables; the other factors entered may simply overshadow ‘valuing’ in its relative importance to predicting pro-nature conservation behaviour, or this result may be due to the items which comprised our composite measure of ‘valuing nature’. Although these items theoretically related to each other and were all equally reflective of valuing nature, statistically this block of items exhibited poor scale reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha of just 0.42. Scale analysis shows that at best, even if the item were removed that referenced how one would feel if certain animals no longer existed, scale reliability would still reach only α = 0.46. Further research is needed to explore this dimension and its relationship to engagement in pro-nature conservation behaviours. All other variables (nature connectedness, indirect engagement with nature, knowledge and study of nature, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviours) emerged as significant predictors of pro-nature conservation behaviours. Lastly, the linear regression was followed up with a commonality analysis to delve more deeply into how these variables might work together to influence pro-nature conservation behaviour. Results revealed that the vast majority (85%) of explained variance of pro-nature conservation behaviour was attributable to overlap across combinations of the predictor variables, with only a minority of variance being accounted for by the combined unique contributions of the predictor variables. These findings reflect the reality of life: human behaviour is complex and necessarily always results from the combination of a myriad of factors—some more influential than others, but all factors acting in concert with each other. Given that multiple, reciprocal factors are needed to explain the behaviour of even simple creatures like sea urchins (Dumont, Drolet, Deschenes, & Himmelman, 2007), attempting to explain, account for, or predict pro-nature conservation behaviour by humans with a model only of isolated factors would seem overly simplistic. At the same time, there does seem to be a foundational influential factor worthy of particular emphasis in accounting for a targeted behaviour of interest. Previous research on the vital importance of nature connectedness for pro-environmental behaviours (Mackay & Schmitt, 2019; Otto & Pensini, 2017; Whitburn, Linklater, & Milfont, 2019) is supported in the current study for pro-nature conservation behaviours. The results suggest that the construct of nature connectedness and related simple activities are influential and foundational factors for the target of pro-nature conservation behaviour. Of variance explained by overlap among variables, 92% was attributable to overlap among nature connectedness and/or simple activities with other variables. This complements Steg and Vlek's (2009) review in which they found that nature connectedness outperformed all other variables (including moral and normative concerns). Our findings are also in line with Clayton and Karazsia's (2020) findings that a general connection with nature was strongly associated with behavioural engagement in pro-environmental activities such as recycling, turning off lights, and overall reduction of behaviours that contribute to climate change. Combined, these findings are in line with the argument, put forth by several researchers, that engagement in pro-nature behaviours is motivated by feeling connected to nature (Frantz & Mayer, 2014; Kossack & Bogner, 2012; Otto et al., 2014; Roczen et al., 2014). Several theoretical models propose that a close connected relationship to nature is inherent within us (Wilson, 1984) and a basic psychological need (Baxter & Pelletier, 2019; Hurly & Walker, 2019). Any deep, personal connection or need gives rise to an inherent motivation to protect, sustain and foster that which we feel close to and that we feel is a part of us and essential to our sense of self (e.g. George, 1998; Ryan & Brown, 2003). By corollary, an elevated sense of nature connectedness (by virtue of it fulfilling a basic psychological need and encompassing nature into our sense of self) appears to engender pro-nature behavioural motivations and subsequent actions. This begs the question as to how to improve nature connectedness and pro-nature conservation behaviours. Traditionally, many efforts have centred on increasing time in nature. While exposure to nature is certainly beneficial, there is a need for a more nuanced perspective. Although much research has demonstrated that people who are more highly connected to nature spend more time in nature (e.g. Asah et al., 2012; Lin, Fuller, Bush, Gaston, & Shanahan, 2014; Martin et al., 2019; Mayer & Frantz, 2004; Tam, 2013), there is also empirical evidence showing that carefully selected nature experiences enhance connectedness (Mayer, Frantz, Bruehlman-Senecal, & Dolliver, 2009; Nisbet & Zelenski, 2011; Passmore & Holder, 2017). Thus, the relationship between experiences in nature and nature connectedness is a reciprocal one. However, similar to the current study's results regarding pro-nature conservation behaviour, several studies have evidenced that how one spends their time in nature and what one's attention is focused on, matters with regard to enhancing connectedness. Passmore and Holder (2017) reported that mere time spent in nature was not a factor in boosting a general sense of connectedness—including to nature, rather it was attending to the emotions that nature evoked that was important. Engagement with natural beauty (Capaldi et al., 2017) and a mindful attitude when in natural surroundings (Nisbet et al., 2019) have been linked to experiencing greater nature connectedness. Noticing the good things in nature (McEwan et al., 2020; McEwan, Richardson, Sheffield, Ferguson, & Brindley, 2019; Richardson et al., 2015; Richardson & Sheffield, 2017) has been demonstrated to significantly boost nature connectedness. This activity involves simply jotting down, daily, three good things that you noticed about everyday nature. Themes which emerged from these ‘good things’ studies included wonder at encountering wildlife in day-to-day urban settings, appreciation of and gratitude for trees lining streets, and awe at colourful, expansive, dramatic skies and views. Evidence also suggests that engaging in certain nature-related activities (e.g. noticing everyday nature, sharing with friends what emotions nature evoked, creating art from nature, eating a wild plant) is of particular importance for increasing nature connectedness (Richardson et al., 2016). Guidance on the types of simple activities3 to engage in, or types of relationship with nature, in order to most effectively foster nature connectedness can be found in the five pathways to nature connectedness—sensory contact, emotion, beauty, meaning, and compassion (Lumber et al., 2017). Each pathway aligns with one of the Biophilic Values proposed by Kellert (1993) as follows. The sensory pathway aligns with the Naturalistic value—taking pleasure from contact with nature; this involves, as the name suggests, engaging with nature through one senses of sight, smell, touch and sound. The emotion pathway, aligning with the Humanistic value—developing an emotional bond with and love for nature—involves noticing the affective state or sensations that nature evokes. Aligning with the Aesthetic value—the appeal of nature's beauty—is, of course, the beauty pathway, attending to pleasing colours, shapes and forms of nature. The meaning pathway aligns with the biophilic value of Symbolism, expressing ideas through nature-based metaphors. This pathway involves using bits of nature or natural symoblism to communicate a concept that cannot necessarily be expressed directly. Lastly, the compassion pathway aligns with the a value of Ethical Concern for and revering nature; this involves extending the self to include nature thereby motivating concern, understanding and helping/co-operative actions. All of the simple activities items used in the current study were informed by both these Biophilic values and the pathways to nature connectedness. Further underscoring the importance that how one engages with nature (as opposed to merely increasing time in nature) is a key to enhancing nature connectedness, Lumber et al. (2017) found that participants who engaged in pathway-informed simple nature activities subsequently reported significantly higher levels of nature connectedness after such activities. While no effect on enhancing nature connectedness was evident for participants who merely went for a walk in nature, showing that the outcome is dependent on walking experience and not the activity of walking itself. All of these simple nature activities and pathways to nature connectedness share an underlying feature or common point, that of embodying relational values—‘a genuine encounter of humans and nature’ (Knippenberg, de Groot, van den Born, Knights, & Muraca, 2018, p. 39). Moreover, when examining the motivations of a sample of 105 committed pro-nature activists from across Europe (van den Born et al., 2018), all these champions of biodiversity in nature spoke of relational motivations in providing the driving force for their pro-nature actions. As Chan et al. (2016) noted, relational values, such as a sense of nature connectedness, make life meaningful in part by virtue of the actions they coax from people—in this case, pro-nature conservation behaviour. Thus, enhancing nature connectedness would serve to not only boost pro-nature conservation behaviour but also people's well-being and meaning in life (see also Howell, Passmore, & Buro, 2013; Passmore & Howell, 2014). With a need for transformational change to aid nature's recovery, the current research provides important direction to increase pro-nature conservation behaviours. First, to improve nature connectedness, the closeness of the relationship between individuals and (the rest of) nature. Second, to engage more people in the simple activities that are associated with nature connectedness, a ‘green care code’ to stop, look, listen and enjoy nature every day. Third, move beyond traditional approaches focussed on simple visits and time in nature. For the transformational change required to address the biodiversity crisis, nature connectedness and simple engagement activities should be the lens for all other activities, from local initiatives to a policy level. For example, urban planning and design should both create habitat and opportunities and prompts for simple engagement with nature, including quiet spaces with reduced noise so one can hear and listen to the sounds of nature. For a sustainable future, education should place connection and simple engagement with nature at its heart. Arts policy should celebrate our connection with nature and prompt simple engagement. Even in health, the wider evidence of the benefits of nature connectedness for feeling good and functioning well (Pritchard, Richardson, Sheffield, & McEwan, 2020) suggests that enjoyment and connection with nature should be a core element of person-centred care. As with all studies, limitations of the current study need to be considered. The data are correlational in nature, thus experimental research is needed to empirically determine causal effects. For example, future research directly testing the efficacy of boosting nature connectedness via simple ‘pathways-informed’ activities (as per Lumber et al., 2017) on subsequent pro-nature conservation behaviour would be informative. Future research is also called for that test how ‘pathways-informed’ activities enhance the other variables our results revealed to be of importance to pro-nature conservation behaviour (i.e. supplemental indirect engagement with nature, knowledge of nature, concern for nature, and pro-environmental behaviour). A broad array of scientific approaches (e.g. qualitative, ethnographic) would provide additional depth and richness to our understanding of variables and factors that predict and drive pro-nature conservation behaviour. A combination of approaches would more fully enable us to understand how these factors work together, and reveal efficacious means by which to improve them. The sample was large; however, participants were based entirely in the United Kingdom; cross-cultural validation of our results utilizing samples from other countries would be helpful. Some items would need to be adapted for cultural and contextual appropriateness. For example, the pro-nature conservation behaviour items would need to be tweaked as the scale was developed and validated with reference to a United Kingdom sample and is relevant to areas with a similar natural environment. Some of the engagement with nature through simple activities may need to be removed and replaced with activities more geographically appropriate; for example, the item ‘collecting shells or pebbles’ as a simple activity to engage with nature directly would not be relevant in a desert environment. It is possible that some factors not included in the study may be of significant relevance, for example differing motives (Molinario et al., 2019; Rode, Gomez-Baggethun, & Krause, 2015), politicized environmental identity (Schmitt, Mackay, Droogendyk, & Payne, 2019) or place attachment (Scannell & Gifford, 2010; Vaske & Kobrin, 2001; Xu & Han, 2019; see also Devine-Wright & Clayton, 2010). Psychological adaptation to climate change and eco-anxiety over climate change and biodiversity crises may play an important role in boosting individuals’ pro-nature behaviour. However, Clayton and Karazsia (2020) found that climate change anxiety was not correlated with behavioural responses. Future studies are needed to examine if similar patterns emerge with regard to eco-anxiety and behavioural responses to the biodiversity crises specifically. For factors that were included, some variable-blocks of items contained more items than others; thus, it is possible that some blocks of items are more accurate than others at capturing respective nature-related dimensions and experiences. While the choice of items in each block is relatively broad, these are not exhaustive lists. It is possible that items not included in the current study would reflect additional dimensions or nuances within a variable-block which could emerge as significant. Although the items did include two validated scales (i.e. the INS; Schultz, 2001 for nature connectedness and the ProCoBS; Barbett et al., 2020 for pro-nature conservation behaviour), utilizing a wider range of psychometrically validated measures will be important in future research. Furthermore, alternative measures of nature connectedness could be employed, such as the Nature Connection Index (Richardson et al., 2019), the Nature Connectedness Scale (Mayer & Frantz, 2004), or the Nature Relatedness Scale (Nisbet et al., 2009), along with the longer version of the ProCoBS (Barbett et al., 2020) scale to more fully assess pro-nature conservation behaviours. Nonetheless, items used in the current study were based on theoretical rationales and previous research, lending confidence to the emergent results reported herein. As a planetary keystone species (O'Neill & Kahn, 2000), we have a responsibility to look after all of life on Earth. Indeed, our very survival depends on it. By definition, a keystone species is a species that has a disproportionately large impact on the communities in which it lives, and on whom the viability of that community thus depends for survival. We humans occupy all communities of this planet. Thus, the viability of ecological systems and the biodiversity which is fundamental to the flourishing of all life—plants, non-human animals, and humans alike—depends on our individual and collective actions. However, the biodiversity crisis shows that our relationship with nature is broken (at the least in the so-called ‘developed’ nations). Our disconnect from the natural world has caused a spiral of disruptions in ecosystems worldwide. To fix this, there is a need to understand both the factors that explain pro-nature conservation behaviours and the types of activity that are associated with these behaviours. Only then can effective measures be taken to improve the human relationship with the rest of nature in a way that will assist nature's recovery. Findings from the current study highlight the vital importance that a close connection with nature, and engaging with nature through simple activities which enhance nature connectedness, play in catalysing efforts to care for and save our planet. Results also suggest these factors work together, and that pro-nature conservation behaviour is more likely to be enhanced by interventions focused on boosting nature connectedness via pathways-informed simple nature activities than by interventions focussed merely on increasing time spent in nature. These insights provide a foundation upon which to develop (and test) interventions geared towards increasing people's nature connectedness and subsequent greater engagement in behaviours that actively, and directly, support conservation of our planet's biodiversity. The urgency of the situation calls for rapid transformational change to aid nature's recovery. The current research provides important direction for local initiatives and policies that centre around engaging more people in the simple activities that build nature connectedness across all aspects of society. In essence, and in practice, we need a Green Care Code: Stop—Look—Listen to the Nature around you. Campaigns centred around such a code would comprise the pathways of sensory contact, emotion, beauty, and meaning, strengthening our connection to nature and moving us to acts of compassion for the beyond-human natural world. Raw data are from YouGov Plc. Total initial sample size was 2,096 adults, 16+ years of age. Fieldwork was undertaken between 29th and 30th July 2019. The survey was carried out online. The data have been weighted and representative of all UK adults 16+ years of age. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. M.R., R.L., R.T. and A.H. survey design was developed; L.B. initial data cleaning was conducted; H.-A.P., L.B. and M.R. review of items for inclusion in the current study was conducted; H.-A.P. and M.R. data analysis was conducted; H.-A.P. and M.R. manuscript writing, editing and review was conducted. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for submission of this article.1 INTRODUCTION

2 METHODS

2.1 YouGov/National Trust survey overview

2.2 Participants

Note

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Dependent variable: Pro-nature conservation behaviour

2.3.2 Predictor variables

Note

2.3.2.1 Demographics

2.3.2.2 Nature connectedness

2.3.2.3 Time spent in nature

2.3.2.4 Engagement with nature through simple activities

2.3.2.5 Indirect engagement with nature

2.3.2.6 Knowledge and study of nature

2.3.2.7 Valuing nature

2.3.2.8 Concern for nature

2.3.2.9 Pro-environmental behaviours

2.4 Analytic method

2.4.1 Factor 1—individual characteristics: Blocks 1 and 2

2.4.2 Factor 2—nature experiences: Blocks 3, 4, and 5

2.4.3 Factor 3—knowledge and attitudes: Blocks 6, 7, and 8

2.4.4 Factor 4—pro-environmental behaviours: Block 9

3 RESULTS

3.1 Hierarchical linear regression

Note

3.2 Additional analysis: Linear regression

Note

Note

3.3 Commonality analysis

Note

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Implications and recommendations

4.2 Limitations and future directions

5 CONCLUSIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

ENDNOTES