INTRODUCTION

The term Body Integrity Dysphoria (abbreviated: BID) describes the persistent desire of an otherwise psychiatrically healthy person for (permanent) physical impairment. The desire to have an amputation and the desire to have paraplegia are the most common manifestations of BID (Giummarra et al., 2012).

It is common for those affected are often under enormous pressure of suffering due to the successively manifesting incongruence between their own intact body shape and the "real", physically disabled body self (First, 2005). Against this background, the desire of those affected for a (permanent) physical disability should therefore be seen as an expression of the attempt to counteract this partly massively discrepant experience of non-correspondence between the actual and the desired body constitution (Blanke et al., 2008; Blom et al., 2012; First, 2005). However, with regard to the Western cultural values, the desire to have a (permanent) physical impairment represents a significant violation of collective conventions. The resulting consequences for those affected by BID are numerous. A self-perception in which one's own feelings deviate from the prevailing norm is fearfully experienced as an anomaly, which massively threatens the possibility of participation in society. In a series of scientific studies it has been shown that the threat of social exclusion activates identical areas in the cerebral cortex, as is the case when processing physical pain. With regard to the active processing of social pain, more neuronal overlaps than differences with physical pain processing could be demonstrated (Eisenberger and Lieberman, 2004; Eisenberger, 2012; Spitzer and Bonenberger, 2012). The attempt to suppress one's own "true" identity as a physically impaired person in order to protect oneself from the feared consequences of such a violation of the norm seems to be the often unavoidable conclusion with sometimes more serious consequences for those affected, such as (severe) depression, etc. which is often the result of a defamatory self-perception (Hilti et al., 2013; Krell and Oldemeier, 2017; Nitschmann, 2007).

Another challenge for those affected by BID is access to adequate medical care. Medical doctors are obliged by the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association to preserve the integrity of the patient entrusted to them and, if necessary, to restore it, but not to amputate a healthy limb (Wiesing and Parsa-Paris, 2015). In relation to Body Integrity Dysphoria, this constitutes a medical-ethical debacle (Dua, 2010; Manok, 2012). This conflict is also reflected in the current legal situation. For example, §228 of the German criminal code (StGB) reads: "whoever inflicts bodily harm with the sufferer’s consent is only deemed to act unlawfully if, despite that consent, the act offends common decency." Gender reassignment, cosmetic surgery, etc. are also carried out on the basis of a psychologically stressful incongruence of those affected and, from a legal point of view, represent "physical injuries with consent". However, in comparison to for instance amputating a limb due to Body Integrity Dysphoria, these do not cause any lasting impairments. No unequivocal conclusion can yet be drawn from this legal discussion (Bensler and Paauw, 2003; Bridy, 2004; MacKenzie and Cox, 2007; Nitschmann, 2007; Pollmann, 2007). The inclusion of Body Integrity Dysphoria into the newly updated international classification of disease (ICD-11) is therefore an important milestone for future adequate medical and therapeutic care. This aid to prevent life-threatening mutilations or other massive self-inflicted personal injuries of BID sufferers, that are intended to provoke an amputation, and often represent the last resort from sometimes enormous psychological suffering (Elliott, 2000; First, 2005; Furth and Smith, 2000; Horn, 2003; Kasten, 2006; Money et al., 1977; Stirn et al., 2010).

The study aims to improve the understanding of BID sufferers and for this purpose examines factors that have a (positive or negative) influence on the coming-out process and the associated quality of life. So far, no clear conclusion can be drawn from this legal discussion (Bensler and Paauw, 2003; Bridy et al., 2004; MacKenzie and Cox, 2007; Nitschmann, 2007; Pollmann, 2007). The inclusion of Body Integrity Dysphoria in the ICD-11 therefore represents an important milestone for the possibilities of medical and therapeutic care for BID sufferers. In order to prevent mutilations or other massive self-inflicted injuries, which are intended to provoke an amputation, for example, and often represent the last resort for those affected out of their sometimes enormous psychological suffering, whereby they often accept life-threatening circumstances in the course of this (Elliott, 2000; First, 2005; Furth and Smith, 2000; Horn, 2003; Kasten, 2006; Money et al., 1977; Stirn et al., 2010). This study intended to contribute to an improved understanding of the living environment of people affected by BID and, to this end, deals with factors that have a (positive or negative) influence on the coming-out process and the associated quality of life of people affected.

HYPOTHESIS

The basis of this study is research on the coming-out process of homosexual, bisexual and transsexual persons (Krell and Oldemeier, 2017; Oldemeier, 2017; Rauchfleisch, 2011), whereby the idea of a process divided into two separate phases (that is inner and outer coming-out) was taken up. So far, however, there is a lack of comparable studies in the relevant literature dealing with the coming-out of BID sufferers, which consequently made it impossible to formulate the alternative hypotheses in a directed manner. Accordingly, it was not possible to decide in advance whether the independent variable had a positive or negative influence on the corresponding dependent variable. Therefore, two-sided questions had to be formulated. The following topics were examined with the help of the hypotheses: symptom expression, desire for body change, pretending (imitation of disability), fear of coming-out, desire to communicate, type of communication, reaction of the social environment, relationship before and after coming out, pressure of suffering before and after coming out.

METHODOLOGY

For data collection, a self-constructed online questionnaire was created, but since no concrete model-theoretical assumptions on the construct of coming out among BID sufferers exist yet, the intuitive construction strategy was used in the development of the questionnaire (Moosbrugger and Kelava, 2012).

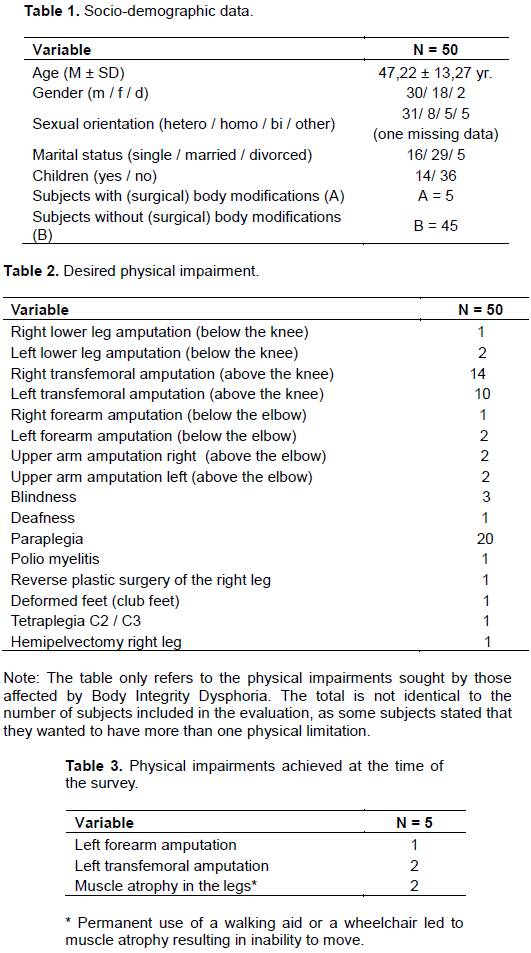

In the course of this, the questionnaire was divided into two independent parts. In the first part, which consists of eight items, the socio-demographic data of the test persons were collected, that is age, gender, sexual orientation, marital status, as well as already (surgically) achieved or still desired body modifications (Tables 1 to 3). The second part of the questionnaire consisted of 52 items. These related to the content of the hypotheses formulated in advance and thus served to test these hypotheses.

The items were answered either on a seven-point bipolar rating scale from -3 (does not apply at all) to +3 (fully applies), on a four-point unipolar rating scale from 0 (does not apply at all) to 3 (fully applies), on the basis of predefined answer options or in the form of an open statement. Against this background, the following statistical evaluation procedures were used in addition to the calculation of frequencies, mean values and standard deviations: In order to be able to determine significant correlations, the rank correlation according to Spearman was carried out as a non-parametric test procedure if the prerequisites for a parametric test procedure could not be fulfilled.

Correspondingly, the Bravais-Pearson correlation was used as a parametric test procedure with equivalent behaviour if the conditions for it could be considered fulfilled. In order to be able to determine significant differences, the Man-Whitney U test was carried out for independent samples as a non-parametric test procedure and the t-test for dependent samples as a parametric test procedure.

In order to test the reliability of the questionnaire, three pairs of items were formulated, each of which asked the same question twice using opposite-pole response scales. The items were placed at different points within the questionnaire. In the course of data cleaning, 69 of 128 subjects had to be excluded from the evaluation because they did not answer >20% of the items. A further nine subjects had to be excluded due to a lack of reliability in their response behavior as measured by the reliability items. In this way, 50 subjects could be included in the evaluation, 74% of whom stated that they had already their Come-out. The respondents were informed about the aims of the study and about the anonymous publication of the collected data.

RESULTS

With regard to symptom expression, no significant correlation could be found with the fear of BID sufferers prior to coming out (r = .207, significance Spearman: p = .110). On average, however, the test persons stated that on a scale of 1 to 4 they were very afraid (M = 3.08 (SD = ±1.16)) of their coming out and the consequences feared in this context (social exclusion, etc.). A significant correlation (r = .300, Pearson significance: p = .017) was found between the severity of symptoms and the frequency of pretending a physical impairment. On a scale of 1 to 4, the subjects stated on average that they felt a strong desire for a (permanent) physical impairment (M = 3.56 (SD = ±.675)) and accordingly often simulated the impairment they wanted (M = 3.48 (SD = ±.762)). No significant difference could be found between BID sufferers with a desire for amputation compared to sufferers with a desire for paraplegia with regard to their fear of coming out (r = .007; U = 125.000, significance U-test: p = .517). On average, both the subjects with a desire for amputation (M = 3.16 (SD = ±1.2)) and the subjects who expressed a desire for paraplegia (M = 3.12 (SD = ±1.12)) stated that they were very afraid of their coming out on a scale of 1 to 4. A highly significant difference was found with regard to the fears of those affected in the run-up to their coming out and the actual reactions of the immediate social environment (family members, friends, colleagues, etc.) (r = .6; t(36) = -4.51, significance t-test: p = .000). On a scale of 1 to 4, the subjects stated that they were very afraid of possible negative reactions from their social environment before coming out (M = 3.08 (SD = ±1.16)). When asked how the person to whom they confided actually reacted, it was found that, contrary to their fears, they reacted positively to their coming out on a scale of -3 to +3 (M = 2.05 (SD = ±2.1)).

No significant correlation could be found between the fear of the persons concerned of their coming out and the way in which this message was communicated on the part of the persons concerned (that is personal conversation, telephone conversation, WhatsApp etc. message, letter) (r = .152, significance Pearson: p = .185). On average, subjects indicated that regardless of their level of anxiety (M = 3.08 (SD = ±1.16)), on a scale of 1 to 4 (1 = "face-to-face conversation"; 2 = "telephone conversation"; 3 = "WhatsApp etc. message"; 4 = "letter") they were more likely to have sought the setting of a personal conversation for their coming out (M = 1.16 (SD = ±.55).

Furthermore, no significant correlation could be found with regard to the influence of a coming out on the relationship with the person to whom the BID sufferers had their coming out with (r = .146; t(36) = .887, significance t-test: p = .809). On average, the subjects indicated on a scale of -3 to +3 that their relationship with this person had neither fundamentally worsened nor improved after coming out (M = 2.03 (SD = ±1.74)), compared to the time before coming out (M = 2.32 (SD = ±1.35)).On the other hand, a highly significant connection was found between the stress caused by the BID symptoms for those affected and the relieving effect of coming out in relation to the resulting pressure of suffering (r = .56; t(36) = 4.154, significance t-test: p = .000). Thus, on a scale of -3 to +3, the test persons stated on average that the degree of stress after coming out (M = 0.7 (SD = ±1.41)) had decreased compared to the time before coming out (M = 2.28 (SD = ±1.6)).

No significant connection could be found between the influence of positive reactions to the coming out of those affected on the part of "like-minded people" in corresponding internet forums and a possible relief from the burden caused by the BID symptoms (r = .21, significance Pearson: p = .109). On average, the test persons indicated on a scale of -3 to +3 that the users in the corresponding internet forums reacted positively to the affected person's announcement that they suffer from BID (M = 3.06 (SD = ±1.1). When asked to what extent these reactions had an influence on the stress caused by the BID symptoms, the subjects indicated on a scale of -3 to +3 that the reactions of other users had neither a positive nor a negative effect (M = 1.31 (SD = ±1.16)).

Also, no significant connection could be found between the positive reactions on the part of the immediate social environment to the coming out of those affected by BID and an increased need on the part of the respondents to want to communicate with other people as a result of this experience (r = .044, significance Spearman: p = .397). On average, the subjects indicated on a scale of -3 to +3 that the users in corresponding internet forums to whom the BID sufferers confided tended to react positively to this communication (M = 2.05 (SD = ±2.1)). When asked to what extent these reactions had an influence on the stress caused by the BID symptoms, the test persons indicated on a scale of -3 to +3 that the reactions of other users had neither a positive nor a negative effect (M = 1.31 (SD = ±1.16)). Also no significant connection was found between the positive reactions on the part of the immediate social environment to the coming out of the BID sufferers and an increased need on the part of the subjects to communicate with other people as a result of this experience (r = .044, significance Spearman: p = .397). On average, the subjects indicated on a scale of -3 to +3 that the persons to whom the BID sufferers confided tended to react positively to this communication (M = 2.05 (SD = ±2.1)), but that these reactions had no influence on the decision to also want to communicate with other people (M = 1.62 (SD = ±2.1)).

DISCUSSION

The question of the present study could be answered with regard to the fact that the reactions of the immediate social environment (family members, friends, etc.) to the notification of the person affected that they suffer from BID seems to have a decisive influence on whether coming out can be a relief for the BID sufferer. In the course of this study, it was shown that the fear of social rejection on the part of those affected by BID, which existed before the coming-out, was not fulfilled and that the coming-out itself did not lead to a worsening of the relationship with the person to whom the BID sufferers had their coming-out. On the other hand, it was shown that the coming-out was perceived as relieving by those affected, due to the positive experience of social support, with regard to the pressure of suffering caused by the BID symptoms. However, the type of reaction of the person to whom the person with BID came out does not seem to have any influence on the further desire of the person with BID to communicate with other people.

Furthermore, it was shown that a high intensity of the individually experienced symptom of Body Integrity Dysphoria and the associated desire for a permanent physical change seems to increase the fear of those affected of their coming out and also has a considerable influence on the frequency with which those affected by BID pretend. It was found that the frequency with which BID sufferers simulate the body modification they desire is conditioned by the individually experienced grandeur of the symptom expression. This result supports the findings of previous studies with regard to the fact that the burden perceived by BID sufferers varies measured by the grand of symptom expression and that fantasizing or simulating the desired physical impairment represents a considerable relief from this very burden, at least in the short term (Kasten, 2009; Stirn et al., 2010). Furthermore, it was shown that BID sufferers with a desire for amputation are just as afraid of their coming out to family members, friends, etc. as sufferers with a desire for paraplegia. The extent to which BID sufferers experience fear of negative reactions to their coming out does not seem to have any influence on the way in which this information is communicated (personal conversation, letter, etc.).

CONCLUSION

Despite the limitations described above, the results of this study are of great importance, as it is the first study to focus on the coming out of people affected by BID. Contrary to the expectations of those affected by BID, it was shown in the course of this work that the fears of social rejection that existed in advance of coming out were not fulfilled. In contrast, it becomes clear that coming out can be a considerable relief for those affected by BID, due to the social support experienced in this context, being allowed to live out their own "true" identity within a liberal social environment, without having to live with the fear of being excluded from participation in society and being degraded to something "abnormal", as well as without the burden of having to conform to supposed ethical and aesthetic norms in order to protect themselves in this way from the feared consequences of social rejection. This leads to the assumption, although this result can of course differ in individual cases and does not represent any relief of the symptoms with regard to the syndrome BID itself, that the probability of the occurrence of comorbid disorders such as depression, etc., which are often the result of a defamatory self-perception (Hilti et al., 2013; Krell and Oldemeier, 2017; Oldemeier, 2017), can be significantly reduced by coming out.

The generalizability of the present results must be considered as limited due to the small sample size (N = 50). In addition, the heterogeneity of the group composition is an obstacle, as the sample, at least in a methodological sense, did not show an optimal composition (Döring and Bortz, 2015). This is primarily reflected in the gender ratio (male: n = 30, female: n = 18, diverse: n = 2) of the sample, as well as the fact that a vast majority of the test subjects opted for the amputation of one or more extremities (n = 27) or paraplegia (n = 14).

It should also be noted that the data on which the study is based was collected within the framework of a field research design. On the one hand, this has the fundamental advantage of being more transferable to practice, but on the other hand, it may have led to increased bias in the response behaviour of the subjects, as there was no possibility to control potentially occurring confounding variables (Döring and Bortz, 2015; Moosbrugger and Kelava, 2012).

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Bensler JM, Paauw DS (2003). Apotemnophilia masquerading as medical morbidity (Case report). Southern Medical Journal 96(7):674-676.

Crossref

|

|

Blanke O, Morgenthaler FD, Brugger P, Overney LS. (2008) Preliminary evidence for a fronto-parietal dysfunction in able bodied participants with a desire for limb amputation. Journal of Neuropsychology 3(2):181-200.

Crossref

|

|

|

Blom RM, Hennekam RC, Denys D (2012). Body Integrity Identity Disorder. PLoS One 7(4):e34702.

Crossref

|

|

|

Bridy A (2004). Confounding extremities: Surgery at the medico-ethical limits of self-modification. The Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 32(1):148-158.

Crossref

|

|

|

Döring N, Bortz J (2015). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften (5. Aufl.). Berlin: Springer.

Crossref

|

|

|

Dua A (2010). Apotemnophilia: ethical considerations of amputating a healthy limb. Journal of Medical Ethics 36(2):75-78.

Crossref

|

|

|

Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD (2004). Why rejection: a common neural alarm system for physical and social pain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 8(7):294-300.

Crossref

|

|

|

Eisenberger NI (2012). The neural bases of social pain: evidence for shared representations with physical pain. Psychosomatic Medicine 74(2):126-135.

Crossref

|

|

|

Elliott C (2000). A New Way to Be mad. The Atlantic Monthly 73-84.

|

|

|

First MB (2005). Desire for amputation of a limb: Paraphilia, psychosis, or a new type of identity disorder. Psychological Medicine 35(6):919-928.

Crossref

|

|

|

Furth G, Smith R (2000). Apotemnophilia: Information, questions, answers, and recommendations about self-demand amputation. Bloomington (Indiana): 1st Books Library.

|

|

|

Giummarra MJ, Bradshaw JL, Hilti LM, Nicholls ME, Brugger P (2012). Paralyzed by desire: a new type of body integrity identity disorder. Cognitive Behavioral Neurology 25(1):34-41.

Crossref

|

|

|

Hilti LM, Hänggi J, Vitacco DA, Kraemer B, Palla A, Luechinger R. et al. (2013). The desire for healthy limb amputation: structural brain correlates and clinical features of xenomelia. Brain 136(1):318-329.

Crossref

|

|

|

Horn F (2003). A life for a limb. Social Work Today 3:16-19.

|

|

|

Kasten E (2006). Body-Modification. Psychologische und medizinische Aspekte. München: Reinhardt.

|

|

|

Kasten E (2009). Body Integrity Identity Disorder (BIID): Befragung von Betroffenen und Erklärungsansätze. Fortschritte der Neurologie Psychiatrie 77:16-24.

Crossref

|

|

|

Krell C, Oldemeier K (2017). Coming-out - und dann…?!: Coming-out-Verläufe und Diskriminierungserfahrungen von lesbischen, schwulen, bisexuellen, trans* und queeren Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen in Deutschland (1. Aufl.). Berlin: Barbara Budrich.

Crossref

|

|

|

MacKenzie R, Cox S (2007). Transableism, disability and paternalism in public health ethics: taxonomies, identity disorders and persistent unexplained physical symptoms. International Journal of Law 2(4):363-375.

|

|

|

|

Manok A (2012). Body Integrity Identity Disorder. Die Zulässigkeit von Amputationen gesunder Gliedmaßen aus rechtlicher Sicht (Vol. 1). Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag.

|

|

|

Money J, Jobaris R, Furth G (1977). Apotemnophilia: two cases of self-demand amputation as paraphilia. Journal of Sex Research 13(2):115-125.

Crossref

|

|

|

Moosbrugger H, Kelava A (2012). Qualitätsanforderungen an einen psychologischen Test (Testgütekriterien). In: H. Moosbrugger & A. Kelava (Hrsg.), Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion (S. 7-26). Berlin/ Heidelberg: Springer.

Crossref

|

|

|

Nitschmann K (2007). Chirurgie für die Seele? Eine Fallstudie zu Gegenstand und Grenzen der Sittenwidrigkeitsklausel. 119:547-592.

Crossref

|

|

|

Oldemeier K (2017). Sexuelle und geschlechtliche Diversität aus salutogenetischer Perspektive: Erfahrungen von jungen LSBTQ*-Menschen in Deutschland. Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung 2:145-159.

Crossref

|

|

|

Pollmann A (2007). Ein Recht auf Unversehrtheit? Skizze einer Phänomenologie moralischer Integritätsverletzung. In: S. Walt, C. Menke (Hrsg.), Die Unversehrtheit des Körpers (S. 214-236). Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

|

|

|

Rauchfleisch U (2011). Schwule, Lesben, Bisexuelle: Lebensweisen, Vorurteile, Einsichten (4. Aufl.). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

|

|

|

Spitzer M, Bonenberger M (2012). Soziale Schmerzen: Warum sie auch weh tun und was daraus folgt. Nervenheilkunde 31(10):761- 764.

Crossref

|

|

|

Stirn A, Thiel A, Oddo S (2010). Body Integrity Identity Disorder (BIID): Störungsbild, Diagnostik, Therapieansätze (1. Aufl.). Basel: Beltz.

|

|

|

Wiesing U, Parsa-Paris R (2015). Die neue Deklaration von Helsinki. In D. Sturma, B. Heinrichs & L. Honnefelder (Hrsg.), Jahrbuch Medizin, Ethik und Recht (S. 253-276). Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin.

Crossref

|