Digital State, Digital Citizen: Making Fair and Effective Rules for a Digital World

Published: July 25, 2020

Latest article update: Aug. 24, 2023

Abstract

The world is connected — governments, business and people are increasingly living and working in a globally connected digital space. People no longer identify themselves as belonging to spatial communities (neighborhood, town, city or country) but by subscribing to digital ecosystems like Apple or Android, Facebook or VKontakte, etc. Governments use digital platforms at the local, regional and national levels to administer certain powers and procedures (even electoral campaigns) and to get feedback from their citizens. As citizens become digital citizens — connected to a wide range of internet resources including electronic government, banking, local management systems, as well as to social media and global internet companies such as Google and Yandex — they simultaneously become subject to rights, rules, laws, and regulations locally and globally. But what are those rights and rules and what do they entail? Who has the responsibility of ensuring that all citizens have equal access to them and are protected from exploitation? What governs the way that global and local digital businesses operate? The article discusses the exercise and protection of rights in online and offline ecosystems in Russia with special attention given to enabling participation by citizens and to multiple stakeholders online and offline. The recommendations and conclusions here may be applicable to all countries experiencing digital transformation.

Keywords

Sovereignty, digital ecosystem, privacy; private lawmaking, human rights online, Digital inequality

Introduction

The world is going through the Middle Ages again. Barbarian tribes have invaded the cosy world of our industrial poleis and brought along their own rules and values. The digital Middle Ages have weakened states, led to the creation of guilds, and countered science with fakery. Fortunately, we know that these Middle Ages will be followed by an Enlightenment. There is only one thing that cannot be predicted. When the Middle Ages are over, will we be subjects or citizens? The answer to this question depends on the strategy that we, the people, choose now. For Russia, which is the principal focus of this article, the main factor in this choice is the interests of various actors. If their interests are or will be merged, i.e. efficiently restrict each other, we have a chance at citizenship. If not, then the main actors can act at will, and we will probably be ruled by a digital monarchy.

In order to analyze the current system of interests and possible ways of transforming it, of managing the transition from the digital Dark Ages to the Enlightenment, three main elements must be taken into account:

- technological, social, and economic factors and risks of transformation;

- transformation of states and state-made laws;

- multinational corporations and their role in shaping social rules.

The analysis of these three elements will allow us to choose the tools and forms of democratic participation by the people — as digital citizens of digital states — in the development of fair and efficient rules for the new digital world.

1. Digital transformation and the risks it brings

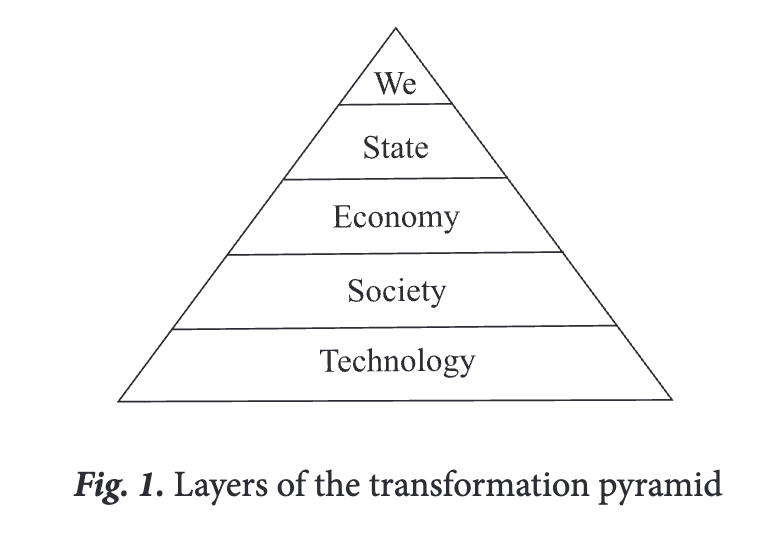

Digital transformation has been analyzed in many scientific papers. For the purposes of this article, it is important to identify the main elements and factors of digital transformation and how they influence each other. Special attention is also given to the impact of digital transformation on the two main subjects of current citizenship relations: the state and the individual. For this purpose, digital transformation can be visualized as a pyramid (fig. 1) based on changes in the technologies whose use is transforming society. Those changes affect each layer above in turn until all of them affect us directly.

Technology is the first layer. Transformation is not pre-determined by technologies, and there is an important question about who will be pushing for transformation and who will be pulled along in its wake. To understand this, we should identify whose interests are fulfilled through the implementation of new technologies.

The present transformation was made possible by the synergistic effect of four technologies: cloud computing, mobile technologies, social networks, and big data [Prokhorov A., Konik L., 2019]. Users of the growing number of mobile devices produce more and more content that can be stored conveniently and cheaply in cloud services. Cloud services facilitate content sharing between users of different mobile platforms regardless of national boundaries. The growth in the volume of content makes new mobile devices and platforms attractive and requires additional cloud storage. The accumulated data “lands” on social networks, making it possible to analyze information from those networks and manage it using big data technologies. The accumulated data is used in turn for advertising and increasing the user value of new mobile services and platforms.

At the societal level, the virtual realm becomes a new kind of spatial one because these two competing environments — online and offline — provide the space for transformation. The virtual world is a new territory, and actual physical territory is the only thing it lacks. People become more a part of virtual communities than of what were formerly the “real” ones: our home communities, neighborhoods, cities or countries. The fate of Hollywood actors engrosses Russians more than the fate of their neighbors. The opinion of a friend on Facebook, wherever they may be, is more important than the opinion of a classmate. People easily entrust their lives to a Gett driver and distrust a prescription written by a doctor at a local clinic.

One after another, borders that separate different countries and cultures from each other are crumbling. Airplanes have made visiting anywhere in the world possible within a day or two. The internet has made any information available within seconds. Online education allows people in one place to develop the competencies that are in demand in another. The last barrier — language — is going to fall: people are beginning to understand each other regardless of the languages they speak. State borders are only in our minds and not exist in reality. No one now cares about the boundaries of the Empire of Timur or the Roman Empire; they died out together with those who remembered them.

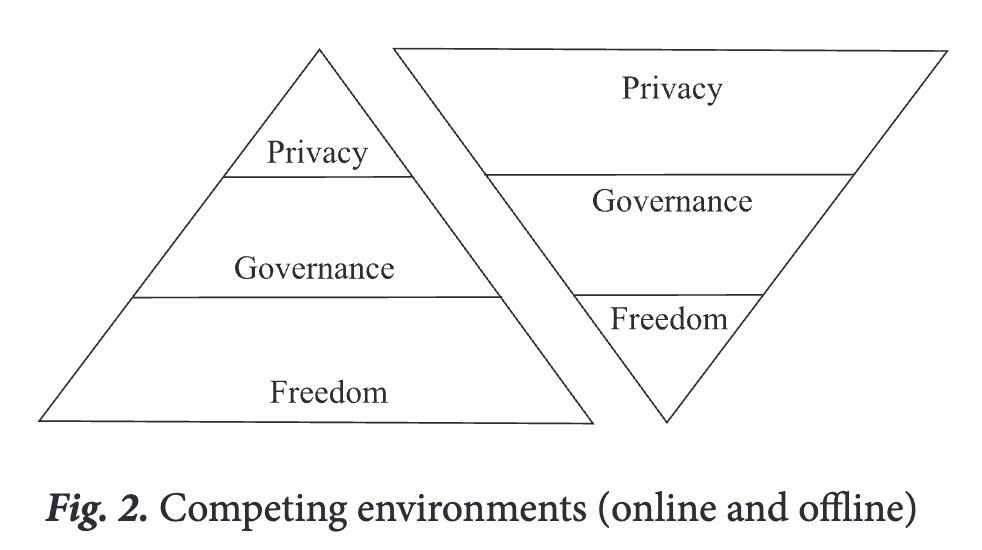

The virtual world has become the main source of trust in Russian society. Russian people do not trust the police, their neighbors or the government; but they do entrust the most valuable things — their social lives, opinions and money — to the social networks, the cloud and online financial services respectively1. What was spatial in the past has definitely become virtual now — identity, mobility, trust. Throughout the 20th century, the source of these things was the City. Neighborhood, factory, school, Institute, clothing style, favorite restaurants formed an identity. Metro lines and city avenues created mobility. Belonging to a team — a school class, an apartment building, or employees of the same organization — was a source of trust. All the same things since the beginning of the 21st century has been born by the virtual world2, the Russian-language internet (Runet but in a completely different proportion. The change in the proportion between identity, mobility and trust in the transition from spatial to virtual communities is best seen in legal institutions such as privacy and personal freedoms (freedom of movement, freedom of economic and other activities), as well as in the management tools used to achieve both of them (fig. 2).

Big cities gave birth to privacy in the late nineteenth century [Warren S., Brandeis L., 1890: 193-220], but privacy is regarded as a dead issue for Internet [Holtzman D., 2006]; [Froomkin M., 2000: 1461]. There is very little freedom left in the urban environment with all its traffic rules, facial recognition cameras and neighbors in condominiums. The city is a normative environment that dictates how people live, what they wear, where they go at night, and what metro line to choose. The internet is by nature a realm of freedom, and that fact has been recognized even by the Russian government3. It is widely believed that the internet is difficult to regulate (there is still no specific law governing the internet in any of the post-Soviet countries). Russian cities, however, are strictly governed not only by appointing (not electing) mayors and city managers, but also through “smart” urban environments and infrastructure. The city and Runet substitute perfectly for one another. The better the internet is, the less people need to live in cities. The “smart” city is no city at all and could just as well be countryside. But a better urban environment is the key to shortening time spent online.

The world economy is experiencing the third wave of globalization [Straw W., Glennie A., 2012]. The second half of humanity — the poor for whom no technological innovations were available previously — has entered the world economy. Consumers of goods and services in the new economy are no longer limited to the middle class because they do not have to pay with money. As the world’s population doubled over the past 50 years, the attention of consumers has become the main object of economic competition. Attention is a limited resource for consumers: an individual cannot use five phones and nine social networks while paying with twenty credit cards. Usually, one or two services in a particular field are used, which means that only few companies can become successful in each market. That is why harmful concentration in many sectors of the economy is the biggest risk for the so-called “attention economy” and why it has been identified by the World Bank as among the three main risks of the digital economy as a whole4- Money has stopped serving as a measure of value (almost everything is free in the digital world), and it is often no longer a source of motivation. The main value in this new world belongs to content provided by users for free. Nobody pays Wikipedia authors, free software developers (like Linux), bloggers, or even most online course lecturers. Judging by the amount of web content, Russian has been the second language of the internet for many years5. Within Russia, there are many websites in the traditional languages of the former Soviet republics (Tatar, Bashkir, Chuvash languages, etc.). Russians of all ethnicities have come together to create all of this because they felt that they were part of the new digital world and wanted to make it better.

Digital ecosystems (such as Google or Facebook) have become digital states with all the elements that were previously found only in a conventional nation state, although the ecosystems have them in a digital form. The digital state has the equivalent of laws (rules of a service or the digital platform’s policies); a population (its users) that exceeds the population of any of the traditional states; and courts and law enforcement bodies (moderators). Soon digital ecosystems will have their own (digital) currencies like Libra and Gram.

With the advent of online ecosystems, even citizenship is no longer merely a relationship between two parties in which one (the citizen) has rights and the other (the state) has duties. In the Soviet Union, for example, the right to vote was exercised by a citizen directly to the state; the state created the conditions for the exercise of this right: it provided information, places and times for meetings with voters, as well as places for voting. Now the interaction of the citizen and the state at elections is accomplished through digital ecosystems, social networks, systems for identification and so on. Instances of fake news, election manipulation, and various internet petitions for certain changes or simply for the resignation of some officials show that the impact of the ecosystem on the state is much greater than the impact of the state on the ecosystem. Sometimes it can be said even that governance in Russia is carried out through these ecosystems rather than that the ecosystems are being governed by the state.

At the same time, it is increasingly difficult for the Russian state to position itself as necessary for the society. Electoral procedures are often replaced by online surveys6. The Central Bank of Russia is working on an e- money project that will not require any supervision7. Blockchain and smart contracts can replace governmental registrars. There are more and more opportunities for decentralized governance in Russian society, but again only by resorting to digital ecosystems.

At the end of this brief description of digital transformation in Russia, it is necessary to focus on the risks associated with it. First, there are problems that Russia and other post-Soviet states must solve but cannot because these problems are global in nature. They are such problems as ecological degradation and diseases (epidemics like HIV, tuberculosis, malaria and polio as well as pandemics like COVID-19). The Russian state will have to recognize that it cannot address these issues alone and that it must begin to do so together with Russian society and other countries using new technologies and ecosystems.

Second, the digital transformation process is becoming a kind a digital rivalry for Russian people. It is still unclear whether Russians will be pushed into digital transformation or whether they can pull Russian government and business into it; whether Russian citizens will become the objects or the subjects of digitalization, or take part as consumers or stakeholders of digital ecosystems. Russians are at present almost entirely excluded from any discussions about their personal data (both in the courts8 and in communities of experts who are developing new laws9), about access to the information on the internet, and about the rights and rules of digital ecosystems.

Finally, Russians are exposed to the same risks in digital transformation as people anywhere the world. These risks include:

uneven distribution of technologies (first of all, in medicine and education), many of which are inaccessible to poor people and small states;

manipulation instead of personal autonomy whereby citizens are being manipulated by data, and the data employed to make decisions has been collected without regard for ethics, privacy and other rights;

vulnerability of Russian culture and the cultures of its national republics to other cultures, often more successful (like European model) or more aggressive ones (like radical Islam);

concentration of economic power in multinational companies, which are almost impossible to compete with and to regulate.

ecological and public health issues, which are in fact a cost incurred by the third globalization but which the state is trying to shift exclusively to its citizens.

These risks affect trust, which is the ultimate goal of digital transformation in Russia. The new virtual world that Russian people trust so much and so much want to trust10 must not deceive them. It belongs to millions of Runet users, not to hundreds of thousands of hackers, not to thousands of officials and not to a bunch of mega-corporations. Russians have no other digital world; neither do our states and digital ecosystems. The value of the digital world is precisely that it is the same for all, and no one can go out and create their own. The only thing we can do is to work together to make it better.

No matter how the transformation takes place, its results must be reflected in the law. Law functions as a kind of DNA for society by reflecting accumulated changes and cutting away everything unnecessary and outdated. However, the main mechanism for creating law — the state — is itself undergoing a digital transformation. Therefore, in the next two sections of this article, we will consider the problems that states face in creating law and examine creation of law by multinational companies as one alternative.

2. States and law-making

The reality of the modern world involves a competition among legal systems because the subjects of law can to some degree choose where to live and conduct their business. There are two strategies for surviving competition. The first is to increase competitiveness, that is, to reduce costs (in the case of law we are, of course, talking about transaction costs) while increasing the utility of the product (we will assume that for law, utility is expressed in the protection of absolute rights, such as property rights and copyright). The second is monopolization, which permits higher costs and lower utility provided that subjects are not free to choose and —this is especially important for law — that they cannot leave the market.

Since the middle of the seventeenth century, states have enjoyed a monopoly on law-making [Backer L., 2007:6]. This allowed law to disregard its own effectiveness, to raise transaction costs (for example, by allowing judicial proceedings to drag on for several years11) and assign a low priority to how useful it is. The main goal of legislation remains erecting barriers. There are external barriers such as national boundaries and the concept of sovereignty. External barriers protect an incumbent state from other competing states as well as from unwanted intrusions by international law. An example of an internal barrier would be the principle of legitimacy, which does not permit competing forms of law-making to exist within a single country (although there is an important qualification concerning federal and regional law-making powers).

In our era of globalization and the information society, monopoly leads both to localization (primarily of data) and balkanization as well as to extraterritorial application of laws. Attempts at localization are being made all over the world, including in the post-Soviet countries12. A total of 80 countries have legislation which contains localization requirements13. The prevalence of various restrictions on the location of data storage in the EU has led it to reduce the number of territorial restrictions on data that is not personal because they were considered an obstacle to economic growth14. Balkanization is a term coined at the beginning of the twentieth century to refer to the collapse of a large state, its fragmentation and the formation of many hostile communities in its place [Todorova M.N., 1997: 33]. In digital terms, balkanization means dividing a global cyberspace which operates according to common rules into a collection of regional networks, each of which has its own standards and norms. States are the main force behind balkanization. But private companies also contribute to balkanization when they create incompatible ecosystems (such as Google and Amazon) and prevent people from using them together.

If localization and balkanization are brought to their logical conclusion, they will end in a digital serfdom in which each user will be tied to a place of production and consumption. Since the internet is the backbone of the modern economy, the entire economy will be localized and balkanized. A state that localizes its citizens will shore up its monopoly position by forcing their subordinate populations to follow its own rules, no matter how inconvenient (or ineffective) they may be. The good news, however, is that enslavement is not possible because of pre-existing competition, the need to reduce costs associated with it, and the effects of scale. In the balkanized Eurasian Economic Union, for example, a company will need to meet five different localization requirements and meet five different sets of standards and norms, while its market will not increase by more than a quarter compared to the Russian one. There are similar factors aligned against balkanization on a global scale. It would not make sense for an Asian company already operating in China, India and Indonesia to comply with EU anti-balkanization requirements because it will increase its market by no more than 10% accompanied by a possible doubling of costs. Localization and fragmentation are incompatible with economies of scale, which require openness and expansion. Thus, localization and balkanization cannot be used without negative economic consequences by states to avoid competition between legal systems.

Another aspect of the competition between legal systems is extraterritorial application of laws. Until recently, laws were connected with a territory — this was clear to everyone. However, the advent of the digital age and attempts by states to maintain their monopoly on making the rules have led to interesting consequences.

The first step toward extraterritorial application of law was the New Public Management (NPM) concept that refers to a series of novel approaches to public administration and management that emerged in a number of OECD countries in the 1980s. The NPM model arose in reaction to the limitations of the old public administration in adjusting to the demands of a competitive market economy. The key elements of NPM were receptiveness to lessons from private-sector management and a focus upon entrepreneurial leadership within public service organizations [Osborne S., 2006: 377-388]. The related concept of the service state took multinational companies as a model from which to copy practices and technologies for governmental management, and it was spurred along by the competition between legal systems that was increasing in the context of the economic downturn. It was an Uber, so to speak, in the public administration market of the 1980s.

The more business management and public administration have converged, however, the more clear it becomes that companies do not have sovereignty the way states do. In other words, companies are not related to a territory in any way. “Citizenship” for companies always implies a contract (for supplies or employment or with customers). As a result, the territory that has always been useful to the state and been considered its main feature along with its population began to hinder it, to limit the sphere in which the state could become a monopoly, and to prevent its regulators from controlling multinational companies. States responded with an aggressive extraterritorial application of their laws.

The United States used many methods before the 1980s to expand its sphere of influence and to instill its values in other nations. By granting military and financial aid “with strings attached” the United States has attempted to influence other states’ policies in the East-West struggle over human rights and in the development of nuclear weapons. Moreover, the United States has used its financial support of international organizations to further its policies including recognition of Israel and denial of aid to Vietnam and Kampuchea [Editors, 1984: 355]. Those actions were in line with the basic principle of international law that all states are equal as sovereigns and may not be coerced or controlled by foreign states15. Those actions remain wholly within that principle because they involve neither coercion nor control of other nations, but rather present those nations with a choice. If a state chooses to accept American aid, it must also accept American political values to some extent. If it chooses to reject those values, it may not enjoy the benefits of United States economic or military assistance [Editors, 1984: 358].

The classic 1979 American textbook on international law stood by traditional standards: state sovereignty is coextensive with state territory and within that territory is exclusive [Brounlie I., 1979: 53]. However, that same year in the Mannington Mills, Inc. v. Congoleum Corp. (595 F. 2d 1287,1292- 1293, 3d Cir. 1979) decision, the court recognized American jurisdiction in antitrust disputes even against foreign nationals operating within the territory of other states and thereby made American competition laws extraterritorial. A little earlier, US law pertaining to securities had been made extraterritorial in effect16, and in the following year protection of human rights around the world was also proclaimed17. US laws passed in the 1980s, such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1982 and the Foreign Assets Control Regulations of 1983, explicitly provided for their extraterritorial effect.

Extraterritorial application of EU law was confirmed (in relation to antitrust law) as early as 1972 in ICI and others v. Commission (1972 ECR619) and subsequently expanded. Extraterritoriality was laid down in the Council of Europe conventions, first in a negative way as additional obligations imposed on relations with “inadequate” countries (Article 12, paragraph 3(b), of the 1981 ETS No. 108 Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data); but then in a positive way as the right to access data regardless of their location (Article 32(b) of the 2001 ETS No. 185 Convention on Cybercrime) and eventually even as the right to regulate data flows regardless of where they are actually carried out (this is already part of Article 3 of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation).

The United States, the EU and other large countries very quickly adopted the principle of extraterritoriality, which severed the link between law and territory. Because these countries wanted to regulate certain relations abroad, states have sacrificed the exclusivity they once had in regulating relations within their own borders. Since the 1980s, a law created by a state is no longer immanently linked to the territory of that state. It may still be considered the rule of “first choice” because it is likely that the courts of that state will apply it rather than any other rule. But it can be no more than that. Hoping to extend their monopoly on law-making by invoking extraterritoriality, states have outwitted themselves and undermined their monopoly.

Once the state has lost its monopoly on making law, its monopoly on coercion cannot help. Laws are usually implemented voluntarily rather than under threat of coercion. Coercive state enforcement constitutes a net loss to society by incurring the cost of courts, bailiffs and prisons. A rule that is perceived as effective and fair, and therefore can be implemented without coercion, will be more useful for society (and for the state) than an ineffective or unfair law that requires huge resources to enforce it.

At this point, unfortunately, it is necessary to express a reservation about the monopoly on law-making in the state. Any state is a complex and extremely heterogeneous public entity in which the rules are in fact created only by a certain subgroup of people. The size and level of representation of the rule-making group in a state varies from country to country. It follows that legislative rules emanating from the state are not based on the interests of all the residents of a particular country but instead on the interests of those who have access to rule-making. However, modern political science studies indicate that democratic states with so-called “inclusive” institutions — those with a model of law-making that takes into account the widest possible range of individuals — enjoy a relative advantage in the competition between countries (i.e., in the competition between different ways of establishing law and order). Countries with “extractive” institutions that exclude a great many people from creating rules end up by imposing rules that ignore the interests of the majority of society, those countries and are therefore less competitive [Acemoglu D., Robinson J., 2012]. The rules adopted by either kind of country are consecrated for both in the name of the state, after which the question of whether they are to be implemented voluntarily or under compulsion arises.

A rule is implemented voluntarily if it does not contradict the individual’s concepts of fairness and effectiveness. Suppose that the law-making segment of society wants to know what is considered fair and appropriate in society. How could this be accomplished?

In democracies the interests of society are conveyed in an organic way to the participants in rule-making through elections. In other words, a person must represent the interests of at least some part of society if they are to become engaged in drafting the law. Taken together, all those who are admitted to the rule-making process will represent a large part of society. In authoritarian states, this mechanism does not work, and other more or less artificial ways must be employed. The most common one would be to consult sociological surveys and other public opinion research (which is also used as a backup mechanism in democratic countries).

Opinion polls in Russia show that people do not consider state law something of their own. Over the past ten years the question, “Do you think that the interests of the government and society coincide in Russia now?” was answered “definitely yes” by only two to three percent of respondents18. Since November 2007 this proportion has fluctuated by no more than one percent. And this consistently high level of alienation from the law indicates that, although the interests of the people are known to those who make the rules, that knowledge does not affect the content of the rules and does not make them more “popular”. The situation is similar with such quasi-democratic ways of “citizen participation in the management of state affairs” as the Russian public initiative19. At the time of writing, none of the initiatives that have gained the necessary support of citizens at the federal level have been implemented in the form of laws. Somewhat more effective are so-called “crowdsourcing” projects in which people act as experts, that is, carriers of special knowledge rather than interests. For example, the federal website regulation.gov.ru allows any registered citizen to comment on a draft regulatory act, and the state body concerned is obliged to consider those comments. The federal project “Regulation of the digital environment” provides for even greater involvement of citizen-experts so that anyone may become a member of the specialized working groups that develop draft regulations for the digital economy.

It is impossible to check the performance of the regulation.gov.ru feedback system because there are no publicly available statistics on whether comments are implemented or not. The relative ineffectiveness of this federal project for regulating the digital environment is indirectly indicated by the mere six acts adopted over the two years of its existence (on digital rights, on crowdfunding, on electronic employment records, on electronic notary services, on changes in the regulation of electronic signatures, and on VAT for electronic services), which is less than one percent of the total number of federal laws passed while the project has been ongoing. The texts of the adopted laws suggest that approving them has been difficult. This is shown by the blanket and cross-referenced norms. For example, according to Article 141.1 of the RF Civil Code, digital rights are to be identified as such in the laws pertaining to obligations and other rights; however, as long as there are no such laws, the rule concerning digital rights does not apply. There are also reservations about a potentially different regulation through special laws, and the lack of detail in the legal rules allows them to be applied directly without by-laws and other regulatory legal acts. Therefore, it is difficult to regard the results of these “crowdsourcing” legislative processes as making “people’s” law. Nor are they rules that will be seen as fair and effective, and their poor quality will prevent them from becoming the “law of first choice” when people make decisions.

3. Law-making by multinational companies

Multinational enterprises barely exist under international law; some scholars have gone so far as to describe them as “invisible” [Jones E, 1994: 893-923]. However, a better metaphor would be the blind men and the elephant. None of the states see the whole elephant. Some states find a headquarters and financial center and think that the company is like an office. Other states find production facilities and think that the company is a factory. Others feel the cargo flows of multinational corporations on their roads and decide that the company is a logistics provider.

Each state sees only those legal entities that operate within their territory, but they fail to see the essence of the entire company because each state by default regulates only the activities that take place within its boundaries. No matter how much states try to extend their power beyond their territories, the extraterritorial effect of the law is the exception, not the rule. Multinational companies are entities that transcend national states and have acquired features such as power, authority and relative autonomy to a degree that would be extraordinary for any domestic entity. Taken as a whole, these features give multinational companies an internal legal system that resembles the comprehensive legal system of a national state. Like states, multinational companies create rules and ensure that they are generally binding, both in a voluntary (legally persuasive) and in a compulsory (legally enforced) manner.

The first feature — power — is inherently relational, typically defined as the ability of A to get В to do something that В otherwise would not do. The political powers of multinational enterprises can be broken down into the following typology [Ruggie J., 2018: 317-333]:

instrumental power, the most traditional form of which is business lobbying;

structural power, which may include companies’ choice of locations and the ability to transfer risks to suppliers;

discursive power, which refers to the ability of businesses and business associations to frame and define public interest issues in their favor — that is, to shape ideas that then come to be taken for granted as the way things should be done, even for non-business entities like governments.

The second feature — authority — is, in brief, the right to prescribe. The sources of authority for multinationals are the principles of private property rights (including intellectual property) and freedom of contract. These core elements of this traditional source of authority are enshrined in, elaborated by, and enforced through public and private law, including obligations under the WTO and international investment agreements20.

The third feature — relative autonomy — may be understood through two possible answers to the question of who owns publicly traded firms: they own themselves, or no one does. In effect, these answers amount to the same thing. There appears to be only one answer to the question on whose behalf multinationals exercise their authority: on their own behalf.

Multinational corporate power is much more organic and portable than state power. It is not tied either to a particular territory or population, and therefore it is not bound by any obligation to make either-or choices when selecting its locations and employees. It is more organic in promoting values and ideas, and those values are simpler and much more aligned to the interests of the people than abstract socialism or liberalism. These factors have worked in favor of corporations before, but in the global information society they make the gap in effectiveness between corporations and states even greater.

It is important to make a qualification here: it is extremely difficult, or perhaps impossible, to describe a multinational company as a single entity with a single mechanism for forming and expressing its purpose or to assign a single identity to it. A multinational company is an ecosystem with a relatively stable core and constantly changing peripheries. This weakens the certainty of the legal system that such a company generates.

The headquarters of a multinational company can determine strategic values, allocate resources, work to create a more favorable environment for the company, and establish the conditions for working with suppliers and employees — but the rules themselves are most likely not determined by the headquarters. They will consist of a set of agreements concluded within the company’s ecosystem and compliance methods chosen by legal entities that are part of the company’s ecosystem in different countries. Therefore, these corporations do not have a macro level of law equivalent to the legislation of states (at least not yet). But at the micro level, when choosing the rules for behavior here and now, the law of multinationals is in force because each person entering the ecosystem of the company has access to the entire set of rules that they are to be guided by in a particular situation. Despite the lack of a macro level legal system, there is an area in which these corporations have a kind of “sovereignty”: their power over themselves. Selfempowerment is already an impressive feature, given the tens and hundreds of organizations, hundreds of thousands of employees, and billions of users bound together by these corporations. And from the point of view of legal certainty, their “law for us” is much better than the “law for them” created in non-democratic states as described above.

The “population” of multinational companies (which is their customers) does not participate in the management of those corporations. Just as there are no states without populations, there can be no multinational company without users. But unlike states, most of which are democratic or seek to be, most multinational companies are authoritarian. A product made by a particular company, whether it is fuel, a car, a phone or a social network, is standardized — the user can choose only to buy or not buy a particular item from the assortment.

The point, however, is that there are multiple users and companies, and together they all form a market. The product market is an environment in which the will of users can be expressed in relation to corporations, and therefore the market restricts the arbitrariness of corporations. The chain of relationships turns out to be long: users (as well as investors and other participants in financial markets) focus on their own interests and on information collected and distributed by civil society organizations and professional communities and by the media. They then adjust their market behavior in relation to the corporations present in the market. But this chain is quite workable, and it corresponds exactly to electoral democracy: both have a certain number of candidates and a large number of users, while each user is limited to a choice between buying or not buying. In their totality — either in the market or in elections — users and voters choose the products and candidates that best suit the overall interests of a given society. The election process is both organic and motivates candidates to meet the interests of the people. The rules created by the selected candidates (corporations) should in theory also correspond to the interests of the voters. This creates a “consumer democracy”, which is the key to digital citizenship.

4. Tools of Digital Citizenship

Citizenship is usually understood as a relationship between a citizen and the state [Mamasahlisi N.M., 2018: 37-47]. This relationship is assumed to be exclusive. However, there is no longer any exclusivity in a plurality of legal systems. Examples of multiple legal systems have been cited many times, but let us consider another one for our purposes: ordering airplane tickets from Russia to Europe. The consumer is located in Russia, which means that Russian legislation applies. But the platform for ordering tickets is American. And the airline is European, with EU law applicable both to transportation (taking into account the requirements of the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization, of course) and to the processing of passenger data. The payment system is from China. At the same time, the ticket ordering platform, the airline, and the payment system have their own rules, which they as global companies have brought into line with the legislation of all possible countries — which means that they do not fully comply with any of them. All these legal systems are applied together with each one claiming its own exclusivity and making no allowance for the others. But strangely enough, all these legal inconsistencies do not prevent the consumer from ordering a ticket, paying for it and flying. At all stages of the process, the participants will more or less understand what they need to do and how to go about it.

What conclusions can be drawn from this example? The main thing is that these legal systems, despite their multiplicity, are compatible with each other. This is due, first of all, to the limits on legal regulation that are insurmountable for any legal system. But, in addition, it is because of the narrow windows of opportunity for creating a rule, no matter where it comes from (a state or a company). Such opportunities for negotiation, or what Lassalle called the actual relations of force, form the connected interests mentioned at the beginning of this article. The parties estimate their costs for establishing a relationship or finding an alternative one, for enforcing a rule or changing it. As a result, the list of possible conditions for a norm (law or contract) is short. It is important to note that this approach to standards is possible when they are created and applied on a mass scale. A single contract or law may not take into account the interests of the other party to the relationship. The legal system on the whole always reflects the actual relationship of power, that is, the sum of the interests and capabilities of all its actors.

There are several historical examples. The 1990s were period when copyright was triumphant. In 1995 the TRIPS Agreement — the “constitution” of copyright holders — came into force. It significantly reduced the number of fair use exceptions to copyright and tightened the enforcement of intellectual property laws. The WIPO Copyright Treaty was adopted by the member states of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in 1996. In addition to many other restrictions, it prohibited circumventing the technological measures of protection of works (Article 11). The golden era of technological copyright protection began with regional codes on CDs and encrypted DVDs and scrutiny of private use. This Copyright Treaty was followed in 1998 by adoption of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in the United States and by the European Union’s Directive 2001/29/EC on the harmonization of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society. When this trend finally reached Russia, it resulted in the amendments to the Federal Law “On copyright and related rights” that prohibited circumvention of technological measures of copyright protection. But 1995 was also the beginning of two decades during which recorded music revenues slumped by over a third21.

Another example is online advertisement. Targeted advertising has been the main source of revenue on the internet since the early 2000s. In an attempt to make advertising even more targeted, online platforms collected all the data they could reach, and banners on sites took up all the available space. Everything changed with the advent of the AdBlock program, which blocked all ads and not just the annoying ones. By siding with their customers, browsers have also blocked third-party cookies22. Taken together, these measures have made the entire industry of real time bidding for advertising pointless. Developing online advertising for two decades without considering the interests of users has made them hostile to it.

It is worth mentioning that other competing companies played an important role in both examples. AdBlock itself began to sell ads (more precisely, to trade in refraining from blocking ads). The hollow victory of copyright holders led to the emergence of Napster, and then iTunes and Spotify. But, in any case, the winners have learned a lesson: the new market situation developed because it is more in line with the interests of users.

These examples show also that the digital citizenship framework is quite complicated. Together with national states, there are at least four other principle actors [Backer J., 2007:13-14]: (i) multinational corporations and other enterprises; (ii) elements of civil society, primarily the economic and human rights non-governmental organizations (NGOs); (iii) media; and (iv) consumers of the products of the corporations, the investment community and financial markets. These actors have fundamentally adverse interests, but are dependent on each other23 and have connections among their interests. The individual’s interests are implemented through a set of tools corresponding to the digital citizenship framework. We shall use the typology suggested by Ruggie [Ruggie J., 2018: 32] to classify potential tools for digital citizenship.

The instrumental and structural power tools of digital citizenship are based on network effects or, more precisely, on queuing network effects. Any system is designed for certain traffic levels, and cannot work properly at peak loads. If users’ activity is in some way coordinated, it will cause a demand peak at certain points in the system, which results in blocking the activity or changing the structure of the system. The best example of such coordinated activity is DOS (denial of service) attacks, which cause targeted websites go out of service. Although any hacking into an information or telecommunication system is illegal, social hacking — advocacy — is legal and quite efficient.

Even in Russia, there are enough tools for digital citizenship, provided that their use is coordinated in the interests of citizens. In addition to the websites roi.ru and regulation.gov.ru and also the federal project for regulating the digital environment, which were already mentioned, there are regional crowdsourcing portals (with names like “active citizen” and “good deed”), and online petition sites in addition to social networks. The actions of individuals using these tools in isolation are unlikely to be noticed, but mass actions are already having an impact on both the state and companies. The use of all the digital citizenship tools of this kind will permit using a multi-stakeholder approach to developing rules of conduct at the level of legislation and corporate policies. A multi-stakeholder approach is not yet a democracy, but it is better than altogether excluding the population from law-making.

The disadvantage of depending on these instrumental techniques is that they are difficult to implement and the least effective of all the tools for digital citizenship. The tools now in use have been specifically designed to make it difficult for the public to influence the rules that the government or companies are making. Yes, this is feedback, but the decision is made by the addressee, not by the people submitting feedback. In addition, using this framework requires substantial resources to pay for the work of the participants that make it effective. Therefore, the multi-stakeholder initiatives are not for the poor.

The digital citizenship tools derived from structural power are more promising. People, like companies, can vote with their feet. For example, online cinemas cannot win the fight against pirate websites in Russia. The more severe the penalties for pirates are (up to a lifetime ban), the higher the number of users of pirate sites24. The same kind of deterrent was used to block the Telegram messaging service. The more efforts the authorities make to block it, the more users it has25. These structural tools are also effective because they are more organic. People are using them not only to express their opinions, but also to switch to using more effective services and thus supporting them. Attention is the main resource of the modern economy. By shifting attention, society rewards or punishes actors.

Discursive tools are even more effective, but also more dangerous. Combining online around certain values allows you to spread these values very quickly. This will lead to changes in the policies of individual companies and perhaps even of the state, but it will create a threat of discrimination for those who do not share those same values. Feminist or orthodox religious movements, support for or denial of the rights of minorities, promotion of certain approaches against domestic violence, stigmatization of certain social groups (for example, law enforcement officers) — all this is dangerous for Russia’s multicultural and multiethnic society. However, within this framework, diverse values compete for the attention of the audience and so mutually restrict each other, and this will prevent the most odious of them from influencing the policies of the state and companies.

The tools of authority are almost never in the hands of the individual. A citizen is always the weaker party in relations with the state or a company. But ultimately the state or company is also people and no one but people. They have the most authority because they are united in a certain institution. All individuals have rights, such as the right to property (including intellectual property), the right to personal data, and the right to an image. By coordinating their actions to implement and protect their rights, individuals will be able to acquire significantly greater contractual power. The institution of collective lawsuits, which was adopted by Russia in 2019, should be quite helpful in this regard. Previously, rights could be defended only on an individual basis. In theory, collective management of personal data (similar to collective copyright management) is also possible. As societies of performers and artists changed the balance of power in the film and recording industry in the mid-twentieth century, collective management of personal data can change the balance of power in advertising and social media.

In conclusion, let us consider relative autonomy. The multiplicity of legal systems is a given. Both the legal systems of states (which are ranked by various indexes, such as Doing Business) and the legal systems of multinational companies are locked in competition. The tendency is to increase competition, not decrease it. Inefficient localization requirements are being superseded by portability and compatibility requirements. The entire framework is much more complicated and includes also elements of civil society, media, consumers, the investment community and financial markets. Each of these actors is relatively autonomous from the others, but together they are all interconnected.

In analyzing the consequences of digital transformation, we have found that it generates ecosystems. With a bit of exaggeration, we could say that the world is being taken over by ecosystems, by both state-owned and company-owned ecosystems, either online or offline. None of these ecosystems owns us fully. Instead, each of us is a citizen of many ecosystems. Our digital world can be made better by influencing digital ecosystems with the instruments of digital citizenship. In a multi-ecosystem environment, it is always possible to find one that meets our interests and use it to change the legal systems of states and companies.

Ecosystems should be considered a common good, not the property of some person or group of people. Therefore, they must be managed as a common good based on the principle of participation of all stakeholders with consideration of the interests of all parties. In other words, the ecosystems should be built and function in a way that is convenient for us to belong to them as citizens. By making ecosystems better, people, businesses and states become better parts of those ecosystems.

Conclusions

Our world has become borderless with everyone connected to everyone. Neither states nor multinational companies can now enjoy any kind of exclusivity. They have to compete with each other for the scarcest resource in our modern economy: people’s attention. As in any market, competition is imperfect, and market failure is possible. But the multiplicity of legal systems and the multiplicity of ecosystems for individuals give them the ability to overcome the failure of one ecosystem (for example, the monopoly of Facebook or Google) by using another ecosystem (for example, the ecosystem of digital resistance). In the digital world, nothing is exclusive.

The same individuals in certain areas of their life can be part of the state (voting in elections, being a member of a political party, participating in local government, being a public servant or even a political figure), a participant in the ecosystem of a multinational company (being a business owner, a shareholder, an employee), and finally just a person (living somewhere, having a family and friends). In each of these areas, people create rules — this is what makes us a society, ensures the consistency of our actions, and gives us certainty. Rules themselves are created only by people and no one except people. The difference is only in the organizational mechanisms for the creation and application of rules.

Given the available tools of digital citizenship — such as instrumental, structural, and discursive power; property-based or contract-based authority; and the relative autonomy of existing digital ecosystems — individuals in the digital world now have a sufficient set of tools to become citizens of digital states rather than their subjects. The main requirement is that individuals be aware of their interests and coordinate their actions with other individuals by choosing an ecosystem from the available framework.

References

- Acemoglu D. & Robinson J. (2012) Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. L: Crown Business, 546 p.

- Backer L. (2007) Economic Globalization and the Rise of Efficient Systems of Global Private Lawmaking: Wal-Mart as Global Legislator, University of Connecticut Law Review, no 4, pp. 1-41.

- Brownlie I. (1979) Principles of Public International Law. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 732 p.

- Editors (1984) Extraterritorial Application of United States Law: The Case of Export Controls. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, vol. 132, pp. 355-390.

- Eroom kin M. (2000) The Death of Privacy? Stanford Law Review, vol. 52, pp.1461-1543.

- Holtzman D. (2006) Privacy Lost: How Technology is Endangering Your Privacy. N.Y: Jossey Bass, 352 p.

- Johns F. (1994) The Invisibility of the Transnational Corporation: An Analysis of International Law and Legal Theory. Melbourne University Law Review, vol. 19, pp.893-923.

- Mamasahlisi N.M. (2018) Citizenship as an Element of the Constitutional Status of the Individual in Russia. Candidate of Juridical Sciences Thesis. Moscow, 214 p.

- May C. (ed.) (2006) Global Corporate Power. New Delhi: Viva Books, pp. 1 -20.

- Osborne S. (2006) The New Public Governance? Public Management Review, no 3, pp. 377-388.

- Prokhorov A., Konik L. (2019) Digital transformation. Analysis, trends, world practices. Moscow: Alyans Print, 368 p.

- Ruggie J. (2018) Multinationals as global institution: Power, authority and relative autonomy. Regulation & Governance, vol. 12, pp. 317-333.

- Straw W. & Glennie A. (2012) The third wave of globalization. Report of the IPPR review. Available at: https://www.ippr.org/files/images/media/files/publica- tion/2012/01/third-wave-globalisation_Jan2012_8551.pdf.

- Todorova M.N. (1997) Imagining the Balkans. Oxford University Press, 257 p.

- Warren S. & Brandeis L. (1890) The Right to Privacy. Harvard Law Review, vol. 4, pp. 193-220.

- World Bank (2016) World development report 2016: digital dividends overview. Washington: World bank, 105 p.