INTRODUCTION

With the popularization of English education in China, the English of college students has been generally improved. However, with the acceleration of economic globalization, the standards for college graduates in China have also been higher and cultivating compound talents with good professional skills and high-level English proficiency has become an inevitable requirement to meet the needs of the development of tertiary education and society. To achieve this goal, in the past decade, English education in Chinese universities has been combined with subjects of college majors, and CLIL has gradually become the mainstream of English teaching. This is also in line with the dichotomy of foreign language learning proposed by Cummins (2008), which means that the learning of CALP (Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency) acquired in 5-7 years can cover the learning of BICS (Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills) achieved in 2-3 years. In this way, the advantages of CLIL are shown. CLIL learners do not compare with native language learners, while they compare with learners who also learn target languages in traditional foreign language classes. Since CLIL learners learn content as well as academic English at the same time, they save more time than their peers. However, its development in China is not optimistic (Liao, 2019). As the 21st century began, domestic scholars imported CLIL-related theories abroad (Chang and Zhao, 2020; Cai, 2013a; Wen, 2019) and promoted CLIL programs in various colleges and universities. However, it is still in the exploratory stage to form theories rooted in the Chinese context. To build systematic and localized CLI teaching theories, teaching materials of CLIL are an essential factor for both teaching and learning. Although there is a wide range of available CLIL materials applied in universities, high-quality CLIL materials shortage is still quite acute, and these CLIL materials have not been analyzed and evaluated in a timely and scientific manner.

This study aims to conduct an empirical analysis of CLIL teaching materials used in Chinese universities to check whether the content and language of CLIL materials match teachers’ and students’ needs. In this way, this study will reveal the value of CLIL teaching materials contributed to training interdisciplinary talents required by the country and the society, providing a scientific basis for further perfecting the localization of CLIL materials.

Theoretical underpinnings

The problems of designing materials for teaching and learning through a foreign language has been widely recognized as one of the main hindrances both in CLIL and CBI for the last three decades in Europe (Banegas, 2012; 2014; Cammarata, 2009; Ioannou, 2012; Mehisto and Asser, 2007; Tedrick and Cammarata, 2012). Though plenty of materials were then available, teachers and researchers soon found out that materials could not be readily applied for local use because they did not respond well enough to the local needs (Bovellan, 2014), which means materials have not been turned into localized materials. Therefore, the proper content and language design of authentic English textbooks that are used in CLIL classrooms are incompatible (Yang, 2019a, b; Banegas, 2017; Medina, 2016; Del Pozo and Estebanez, 2015; Möller, 2017). Ball (2018:222) maintained that “the scarcity of availability or utility of CLIL materials is documented throughout Europe and there is a lack of clear guidelines for the daunting task of preparing materials”. Many scholars have emphasized the difficulty of teachers in finding suitable teaching materials for the CLIL programs and pointed out that it takes a lot of time to adapt or create the materials (Banegas, 2012; Bovellan, 2014; Bonnet, 2012).

Scholars probed into the shortcomings of CLIL teaching materials. Coyle et al. (2010) agreed that CLIL textbooks published under the EFL umbrella often ignore the balance between content and language expression, courses, modules, and units. In some cases, publishers provide translated versions of regular textbooks written in the learner's first language (L1) without any adjustments to meet the requirements of the new teaching contexts. This international EFL or CLIL-oriented textbooks usually lack cognitive involvement or connection with the local context since their purpose is to adapt to a wide range of educational environments. They are usually not suitable for integrating subject and language learning (Banegas, 2012; Tomlinson, 2012). Kelly (2014) and Lopez-Medina (2016:165) summarized some of the shortcomings of teaching materials in different majors found by CLIL experts. One of the obvious shortcomings is insufficient scaffolding in terms of the language support that students need in the subject matter which can be provided as supplementary resources of the textbooks in the form of posters, booklets, or in the textbook itself alongside the task. Others involve insufficient attention to the cultural dimension, low attractiveness, and separation of interest from learners, etc. Scholars' research on CLIL textbooks seems to be mainly based on the needs of teachers. Morton (2013) investigated the practice and views of European CLIL teachers including finding, adapting, creating, and using materials in secondary education, and found that most teachers would be willing to create their CLIL materials. In other words, according to the specific environment, the local school culture and curriculum should be considered, and the efforts of CLIL practitioners should be included while developing CLIL teaching materials.

What often seems to follow from the lack of appropriate teaching materials for CLIL is the evaluation of CLIL teaching materials. Coyle (2007) attached great importance to contextualization in the 4Cs framework to ensure the success of CLIL-based learning across different contexts. In the specific context of CLIL, the textbook aims to respond to the 4Cs framework of CLIL proposed by Coyle (2007). This framework involves content, communication, cognition, and culture. By considering the type of language students need to learn specific content and to communicate in tasks with certain cognitive needs, it concentrates on the integration of content and language. Communication is further decomposed into "language of learning", "language for learning" and "language through learning", which means subject-specific language, the language required to complete classroom activities, and the language produced by students’ learning, respectively (Coyle, 2009). Culture is understood as surrounding other Cs or related to learners’ communities and cross-cultural learning. Integrating content and language, rather than thinking about one or the other, has also become a significant teaching focus of CLIL (Nikula et al., 2016). In other words, the design should ideally adapt to the development of learners' communicative ability, content knowledge, cognitive ability, and cultural awareness. Mehisto (2012) lists 10 criteria for creating CLIL-specific learning materials as well as other requirements and provides examples of how to apply each proposed criterion whilst also providing a corresponding rationale with references. Medina (2016) proposed a tentative twofold checklist. On the one hand based on previous checklists created to evaluate ELT textbooks, and on the other hand, on the criteria for producing quality CLIL learning materials drawn up by Mehisto (2012). Ball (2018) canvasses some of the innovations, offering several initiatives that have led to the production of specific CLIL materials and describing and analyzing their assets and possible pitfalls.

Compared with foreign researches, domestic researches mainly focused on theoretical studies. According to Cai (2013b, 2016), many teaching materials of subject-based English (SBE) published in mainland China are more English-Chinese bilingual education than CLIL. Failure to study the CLIL theories and their development leads to pseudo-CLIL materials which have created misunderstanding and even fear of CLIL among English teachers. Hence, textbooks act as a barrier to the development of CLIL in mainland China. Scholars like Cai (2019) pointed out that the implementation of CLIL in Chinese colleges and universities involves the orientation of universities and a complex transformation of foreign language teaching, textbooks, and tests, which are challenging to reach a consensus. Thus, there is still a long way to go to enhance the quality of CLIL textbooks in China.

To put it in a nutshell, since traditional paper-based textbooks are being impacted by multi-modality and technology, the teaching and learning resources for the class are becoming more and more diversified. Thus, in this paper, teaching materials will comprise almost everything from traditional textbooks to digital materials. Although still an under-researched area, there has also been a steady growth of studies into CLIL teaching materials as a hindrance to the CLIL implementation in the global context in recent years. Nevertheless, there is still a long way to go to enhance the quality of materials. On the one hand, although foreign researchers have more comprehensively explored available materials in the implementation of CLIL, they mainly focused on CLIL teachers’ needs, while ignoring students’ attitudes towards CLIL teaching materials. On the other hand, relevant researches at home become much scarcer and they keep citing the existing theoretical results of foreign countries (Liao, 2019). A small number of scholars conducted empirical researches in local universities. Given the dearth of related researches about evaluation carried out on CLIL-specific materials, this paper aims to explore the possible hindrances brought from teaching materials from the perspective of 4Cs in Coyle’s model (2007) including content, cognition, culture, and communication as well as language. It sets out to contribute further evidence to the already existing, regarding the rarely studied background of tertiary schools and materials.

METHODOLOGY

Research questions

With the above overarching objective in mind, the study addresses the following research questions: what are the views of teachers and students on CLIL teaching materials concerning content? What are the views of teachers and students on CLIL teaching materials about English learning? What are the views of teachers and students on CLIL teaching materials concerning cognition, culture, and communication (4Cs in Coyle’s model)?

To address the above questions, the study presented in this section was undertaken. Qualitative data were collected by interviewing 3 teachers and 8 students in different Chinese universities, accepting the invitation to be interviewed willingly. The semi-structured interviews were conducted by the researcher and took place between April and June 2020. This form of data collection was chosen to allow for a multi-faceted, holistic insight into teaching materials applied to CLIL classes that enabled the researcher to investigate the hindrances existing in textbooks. All of the interviews (n=11) were done through WeChat video to avoid face-to-face communication because of the spreading of COVID-19.

Context

In this study, teachers and students in 9 different universities were invited to have semi-structured interviews. These 9 universities are mainly in Zhejiang Province, Jiangsu Province and Shanghai. One of the universities is in the list of Project 985, one in the list of Project 211, and the other three key universities. Universities in these three places have a high-quality education and they are pioneers in the implementation of CLIL in Chinese tertiary education, which can reflect the overall picture of CLIL implementation in China.

Participants

One major hindrance to CLIL teaching materials based on the fact that CLIL materials have to be addressed to the applicable linguistic and cognitive level of their intended target groups (Bovellan, 2014). Thus, in the process of teaching and learning, the target groups have to be taken into account, which becomes a more visible and recognized demand in CLIL pedagogy. In this respect, both learners and teachers have a say in assessing the CLIL teaching materials.

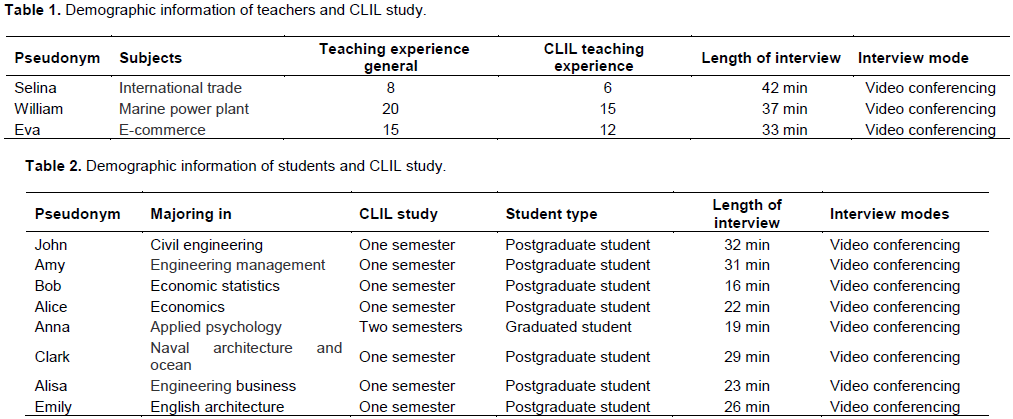

Three CLIL teachers including one language teacher and two subject teachers were invited to have one-to-one semi-structured interviews. The language teacher Selina has given this kind of lessons for Business English majors for eight years in a university in Zhejiang Province. One of the subject teachers William has classes for Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering in a university in Jiangsu Province for almost 20 years while the other subject teacher Eva courses for Economics and Management for nearly 14 years in the same university. The author acquainted herself with these teachers when she was earning her bachelor’s and master’s degree respectively in these two universities. Selina became an undergraduate instructor after receiving her master’s degree in China while the two subject teachers went abroad for their doctorate degrees. Table 1 outlines all the interview participants and their interview-related information.

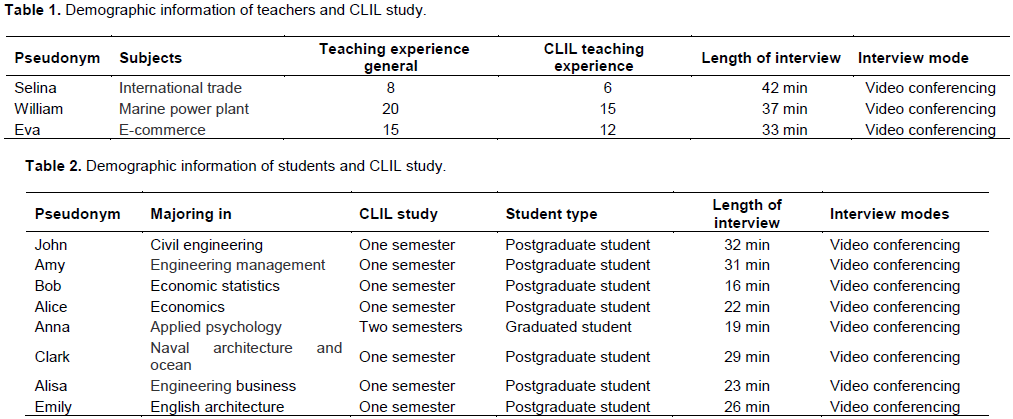

Altogether 8 student participants were Chinese graduate students in different Chinese universities (3 male and 5 female). Those participants had CLIL classes as they were undergraduates and the amount of CLIL studying experience stretches from one to two semesters. These 8 participants all had a high GPA in their courses especially their CLIL courses when they were undergraduates, which can prove that they joined the CLIL classes actively and that they had a deep insight into the CLIL courses. Since they were all born and grew up in Hangzhou, the capital city of Zhejiang Province, they have had traditional English classes for at least 13 years from Grade Three in primary school to the senior year in their universities, which provided a solid base for their CLIL courses. After graduation, four participants furthered their study to be post-graduates while one gained a bachelor’ degree and started to work, which helped the researcher to actively generate a diverse sample to capture as many perspectives as possible. At the very beginning, the researcher explained what CLIL pedagogy is to these five students. Checking that they all comprehend the concept the CLIL and that their experience of CLIL classes fits in with the research aim, semi-structured interviews were conducted. In the process of the interviews, five students all looked through their CLIL textbooks to give more detailed feedback. Table 2 outlines all the interview participants and their interview-related information.

All participants were given a digital information sheet outlining the study, how data would be used as well as information on confidentiality and anonymity. Participants signed the accompanying consent form and fill out the bio data sheet before being interviewed. In the interest of the participants, all names, places, and other possibly identifying information have been anonymized. All the participants were thanked for their contribution with a small gift.

The interviews lasted approximately half an hour, with the shortest being 16 min and the longest 42 min. To increase reliability, validity, and misinterpretations, the data were coded checked by eight participants again. Since all of the interviews (n=11) were conducted in Chinese, for this article, any data extracted from the Chinese interviews have been translated by the researcher.

Instruments

Purposive sampling refers to a sampling process in which samples are selected by the researcher with a specific purpose in mind (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). The use of purposive samples requires expert judgment about the suitability of the sample and a well-reasoned argument for why a particular set of respondents provides an adequate basis for survey-experimental inference. This paper aims to obtain a deep understanding of hindrances existing in the process of implementation of CLIL in Chinese universities as well as teachers and students as the main part of the class should have a voice in this research. Therefore, 3 teachers and 8 students suitable at all points were invited.

Two structured interview protocols, one for teachers and one for students, were developed by referring to the Criteria for producing CLIL learning material listed by Mehisto (2012). Hence, all the interviews followed the two interview protocols, which both consisted of three sections, eight questions exploring the textbooks’ content, the language, and other existing hindrances.

FINDINGS

To answer the three research questions, this paper initially intended to present teachers’ and students’ good or bad reviews. Interestingly, however, interviewees focused on the existing hindrances of CLIL teaching material. Therefore, this section explored hindrances existing in textbooks revealed by the 11 participants. The first part stated the hindrances in terms of pedagogical results identified in content knowledge and language. The second part reported the hindrances from the perspective of textbooks’ communicational, cultural, and cognitive function involved.

Pedagogical hindrances

Students and teachers are the main roles in the background of teaching and learning. Teachers play the role in transferring knowledge from teaching materials to students. In this process, teaching materials are only a subsidiary tool to remind teachers of what to teach in the next stage and to help students preview the knowledge taught in class. When students meet problems, they would first turn to their teacher for help instead of textbooks. In this sense, the teacher becomes the most significant factor that would affect the pedagogical results. According to the interviews, teaching materials fail to meet students’ needs in content and language learning leading to pedagogical failure.

The invalid access of content knowledge

Content and language account for a great proportion of the quality of textbooks. Universities in China barely provide CLIL teaching training for teachers, but they give teachers more freedom to arrange teaching materials. That’s why teachers will give lessons with the rearranged teaching materials based on the general cognitive level of their students and their understandings. The teaching materials in the form of PPT cannot completely match their textbooks. The content knowledge in textbooks have surpassed students’ learning capacity just as one teacher and one of his students mentioned in the interviews:

William (2020/05/09): This textbook we are using is extremely challenging for students to learn since it has many difficult concepts. However, the students in this class are going to study abroad in Russia in the second year of their graduate studies so the managers of this university require teachers to attend classes in English. Although I know that students may not understand, I still have to speak in English. I find myself in an embarrassing situation.

Clark (2020/05/04): We students majoring in Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering mainly rely on self-study. The teachers teach in English and we cannot completely understand. The textbook is also in the English version. We can do nothing about it so we bought the Chinese version of the textbook to help us absorb what our teacher said.

Three of the participants said that the difficulty of the content knowledge has been lowered, which is suitable for the introduction and explanation of some basic knowledge, so teachers will supplement the knowledge that textbooks do not have.

Alice (2020/05/05): The teaching method of CLIL was only applied in several courses in my freshman year, and the coverage was relatively narrow. The difficulty of content is moderate. Most of the content in the textbook can be understood, which is more suitable for freshman students. In other words, it is unconducive for students to learn advanced content knowledge and improves their English.

John reflected that the difficulty of their English textbook is equal to the Chinese version. In his university, CLIL is only implemented in one excellent class, and the other classes are taught in Chinese, which can be regarded as control classes and an experiment class. He stated that the excellent class was tested with the same knowledge as other classes in the final examination but the language of their test paper is in English. Bob revealed that the textbook was too difficult to understand and they need to be used together with the Chinese version of the textbook. Comparing these two versions of textbooks which are only different in language, he said the English textbook is more professional in explanation and more helpful for learning.

From this perspective, one of the hindrances existing in the teaching materials nowadays is invalid access to content knowledge. The subject knowledge of teaching materials may be within the reach of students taught through their mother tongue. But coupled with language teaching under the guidance of CLIL pedagogy will increase the difficulty in comprehending, which is also a problem that teachers are facing. If there is a gap between the content knowledge of teaching materials and students’ cognitive level, it will affect the learning results and lower the utilization rate of textbooks. Textbooks introduced directly from foreign countries are more like the current CBI textbooks, and teachers also pay more attention to the teaching of subject knowledge. In this sense, we can also see that the teaching materials are designed with teachers’ subjective consciousness. If teachers believe that this is a teaching that pays more attention to subject knowledge, the corresponding teaching materials are also subject to content knowledge.

To sum up, teachers are the regulator who can match students up with the new knowledge by combining the available materials. Besides, the new theoretical lens, translanguaging, can be applied to the CLIL classrooms, such as explaining in Chinese when students find it hard to understand (Nikula et al, 2016).

The invalid access of target language learning

CLIL textbooks should have improved the English level of students; however, the interview results contrast with the theory.

Taking the majors of all participants into consideration, it is obvious that the participants who have science degrees believed that CLIL textbooks did not help them learn English. Since the contents of science and engineering were mainly about formulas and calculations, the English involved was limited.

John (2020/05/12): English textbooks can be understood in terms of language. But it is not very helpful for English learning as this depends on majors. The nature of physics is mathematics, which is mainly about formulas, so what we have learned is mathematics instead of language skills.

The participants majoring in social science said that CLIL textbooks helped them learn English to a certain extent, especially in reading and writing. However the listening skill did not improve, because there were no relevant exercises in the textbook.

Alice (2020/05/07): I improved my reading and writing ability. But due to the lack of language environment in the class and the teacher's English is not so native, my listening and speaking have hardly improved.

One of the participants said that their textbook is a global textbook particularly written for L2 learners, which is more appropriate than the ones written for L1 learners. Though the quality of textbook language is guaranteed, students in this class have not improved their English yet. As seen from the interviews, teaching materials do not fully consider students’ proficiency level of L2. Therefore, it is widely acknowledged in CLIL literature that materials must be adapted or written specifically for a particular target group, which means the localization of CLIL materials (Llinares and Evnitskaya, 2012; Morton, 2013: 114). In this way, the content and language of authentic texts are adjusted to the level of the target group.

Content teachers and language teachers added to that:

Alias (2020/05/13): The textbook does not give guidance in the presentation of vocabulary. Therefore, language is not specifically used as one of the teaching goals. But I will explain new words that are occasionally encountered in the process of teaching or when students ask questions and cannot understand.

Emily (2020/05/17): The textbook we are using doesn’t suggest aids for pronunciation. The teaching materials designed by us based on the textbook will explain the language knowledge points, but you know that the time of a class is always limited. It is really difficult to balance the teaching of language and subject knowledge. No one will tell us what to do, and we are still in the process of exploring. The main point is to look at the reaction of students. The teaching that they are satisfied with is exactly good.

This also shows that subject knowledge and language are inseparable. According to the interviewees, students who reflected content knowledge was difficult thought that the language was also difficult. The more subject knowledge involved, the more expressions of academic English are needed. And the two add up to increase the difficulty. However, students who are exposed to such textbooks generally believe that their English has improved, while the students who think it’s easy to comprehend the language think that the subject difficulty is also reachable. The reason is that language in the textbook is mainly in the category of BICS, which is in line with the students' foreign language proficiency. All in all, Chinese CLIL textbooks are at two extremes, extremely challenging and easy. There are almost no textbooks that students claim that language and subject knowledge are both within the scope of appropriate learning.

Functional failure

One obvious distinction between high schools and universities is that universities enjoy a higher degree of freedom reflected in the selection of textbooks. Teachers may choose two or even more textbooks in one course

so that the advantages of those textbooks can be combined to help students comprehend the knowledge more thoroughly. When asked about the utilization of textbooks, participants reflected that the usage rate of the textbooks is not so high since these textbooks seldom completely meet the needs of classes and teachers would supplement the content of textbooks.

Amy (2020/04/11): The utilization rate of my textbook was not so high, but our teacher designed the content knowledge mainly based on the textbook. And there were many supplements since most of the textbooks are descriptive and lack specific examples. Teachers would generally show specific cases to students.

Bob (2020/04/23): The textbook was only used for the final exam. My teacher had classes following the content of PPT, which provided detailed information.

One result of the low utilization rate of textbooks may be the use of PPT. Participants who reflected that textbook is rarely used by them showed that their teachers mainly used PPT in class instead of textbooks, which has become a common tool in teaching and learning. In Alice’s view, a satisfying textbook would be applied to classes more frequently, but it would not be the only tool for instruction.

Alice (2020/05/05): The utilization rate of the textbook was higher than I supposed, and the PPT that matches with the textbook was used at the same time. It is easy for students who are non-native speakers to catch up with the class.

In this sense, PPT is equal to the textbook of the course and can even replace it. PPT shows a multi-modal application in teaching, which helps students to learn and teachers to teach. The content of PPT may have already integrated the content of several textbooks thanks to teachers’ DIY (do it yourself) approach of CLIL materials. Students who do not read their textbooks will never find it. Hindrances in terms of cognition, culture, and communication make textbooks lose their function and even be replaced.

The invalid access of 4Cs

The first C, content has been investigated above. In the last research question, participants were interviewed about the hindrances existing in terms of cognition, culture, and communication. Two participants said that the textbooks are good enough and do not need to be improved. There are two possible reasons. The universities of these two participants are in the lists of Project 985 and Project 211.

Thus, the quality of education is much higher than in other universities. The second reason is that teachers have put supplementary teaching materials in place so that students are satisfied with the overall content of the course.

Except for the hindrances of unmatched content and language, participants stated other existing issues related to cognition, culture, and communication.

Amy (2020/04/11): The textbook has been published for a long time and there is rarely new knowledge for us to learn. And it is mostly about overviews and requirements. It is a lack of cases to illustrate. Adding cases can help students to master professional knowledge more firmly.

Bob (2020/04/23): It is good. But it will be better if more practical knowledge could be integrated into the textbook, otherwise, we don’t know how to use this theory.

Amy and Bob both are concerned about a lack of attention on cognition due to outdated textbooks. They thought that textbooks are inadaptable and rigid which have been published for a decade. Textbooks they used only focus on mountains of theories rather than practical abilities, which are not instrumental in developing thinking skills (Peyró et al., 2020). Participants majoring in social science reflected that authentic textbooks consist of articles related to this subject singularly, suggesting that a brief introduction of this article in learners’ first language would be welcomed by students.

Clark and Alisa expressed that textbooks should be designed to attract the attention of students. As academic English is often decontextualized, CLIL textbooks with no pictures linked with contextual information cannot help students process the knowledge (Gómez Ramos et al., 2020). Textbooks generally employ useful patterns of language repetition to facilitate retention and imitation which will also make students drowsy. Describing, defining, explaining, or evaluating may create a ‘bridge’ to link content, literacy, and language and thus avoid the artificial separation of content and language that still pervades much CLIL practice (Morton, 2020). Adding more exercises of efficient communication will cultivate the positive of students. Adding more exercises in the current teaching materials will cultivate the positivity of students.

Alisa (2020/05/16): To save time, we will leave the task after class. The final results will be displayed in class. Some after-class exercises are more challenging but never underestimate our students. Give them time and they will keep surprising you.

Clark (2020/04/03): There is not much time for us to do exercises and discuss problems in class. But after class, we need to do teamwork to complete the tasks assigned by the teacher. There will be more exchanges with classmates, but without the supervision of the teacher, our communication is still in Chinese. The teacher will ask us to use English when we report in class, so oral English will be improved to a certain extent, which is not obvious. After all, you might give a report only once a semester. Maybe the teacher can assign us tasks that need to be communicated in class.

Just as Clark mentioned, in CLIL classrooms, students only passively accept what the teacher taught. Occasionally the teacher will ask questions, but if there is no response from students, the teacher will directly give answers. Therefore, students must seize the opportunity for communication.

Communication and cognition cannot be split into two distinct parts. Students have frequent communications with each other to carry through a task. Many tasks are quite challenging, so students can’t deal with them casually. They need to review the knowledge they have learned before and cooperate with their classmates to complete it. When they finish the task, they will feel quite fulfilled. Students believe that they have mastered new knowledge and skills. Exercise for discussion and communication will not only improve communicative skills and cognitive capacity but also bring more content and cultural knowledge.

Cultural knowledge is another factor that has been neglected in CLIL textbooks so that much of the knowledge is only imperfectly understood.

John (2020/04/11): There will be relevant cases from abroad in the textbook, which I wonder is considered cross-cultural. It seems that there is no special reminder of the cultural differences that we should pay attention to. Because the textbook is a foreign textbook, there is no mention of the domestic situation. Culture is implicit in it, and there is no special section to list points for teaching. It will be better to provide more cultural knowledge. Commonly, we know the word and the grammar but we can’t understand what it means since we have no knowledge background.

William (2020/05/07): Culture is a profound but very common thing. We can't explain it specifically. Therefore, the designed teaching materials are also based on the teacher's personal experience. The richer the teacher's personal experience is, the more cross-cultural knowledge that students can learn.

Cognition, culture, content, and communication are involved with each other rather than four separate aspects of CLIL. From this, we can find that CLIL teaching materials are not localized, and most of them are directly imported from abroad, which is exactly the crux of the problem (Zhao et al., 2020). However, the teaching situation abroad is different from that in China. Similarly, even the situation of colleges and universities in different regions of the same country is different. Therefore, the localization of foreign teaching materials is the general direction of development, and it is the responsibility of teachers to integrate the teaching materials with the uniqueness of universities.

DISCUSSION

To answer the first two research questions, this paper found the same results as previous studies that authentic materials accommodating both content and linguistic needs of their target students are rarely found (Tomlinson, 2012; Yang, 2019a). On the one hand, content knowledge of textbooks is simplified due to the integration of the foreign language. On the other hand, the difficulty of the language is also decreased facilitating the comprehension of content knowledge. In this sense, CLIL is placed in an embarrassing situation in contrast with its purpose of motivating both content and language. Participants stated that CLIL textbooks in Chinese universities principally focus on academic English, which will be helpful for post-graduate students to read literature, but the corresponding assessment of English is not based on academic English. Thus, to some extent, if the participants’ CET-4 and CET-6 which assess English from the four aspects of English listening, speaking, reading, and writing have not improved, they would deny CLIL textbooks and conclude that CALP does not cover BICS. To cooperate with teachers in the CLIL classroom and bring ideal outcomes, students should also walk out of the comfort zone and establish a sense of urgency to strengthen English learning. During the interview process, this paper found that CLIL courses are not compulsory courses, but optional ones. If a student believes that his or her poor English will lead to the failure of examination of CLIL courses, he or she will not choose them, thus forming a vicious circle.

To answer the last research question, CLIL textbooks do have some major disadvantages to meet students’ needs of cognitive development, cultural knowledge, and communication skills. Based on the hindrances existing in textbooks, suggestions are proposed from the following aspects answering the last research question. Firstly, language difficulty should be appropriate to the students’ level of L2 or be slightly higher than the level of contemporary college students. It will help students realize the correct role of language-language of learning, for learning and through learning. Textbooks can be equipped with Chinese versions to assist learning if conditions permit, but teachers should control the extent to which students use the Chinese version of the textbook during the course, otherwise, CLIL didactics will not work. Concerning content, textbooks have to cover the contents of the curriculum and the content is appropriate for the students’ cognitive background and relevant to students’ experiences. Besides, the activities suggested for practicing the content are varied. Considering other hindrances such as a lack of practical and cultural knowledge and a scarcity of illustration which is following Meyer et al. (2010)’s studies, textbooks should include the 4Cs of CLIL (content, cognition, communication, and culture) within CLIL textbooks (Medina, 2016). In terms of cognition, textbooks should cater to the needs of different learning styles and activate previous knowledge with challenging and motivating activities. Taking communication into account, textbooks stress communicative competence in activities to encourage teacher-student and student-student communication in and out of class. Regarding cultural knowledge, textbooks should relate content to the sociocultural environment and guide students in developing cultural awareness.

Previous scholars witnessed CLIL textbooks from teachers’ perspectives, stressing teachers’ difficulties in finding suitable and inevitable textbooks for their CLIL programs (Banegas, 2012; Morton, 2013; Bovellan, 2014). This paper investigates CLIL textbooks foregrounds students’ point of view, to whom textbooks are like a walking stick. That means textbooks are dispensable for students. In this sense, the researched hindrances in textbooks of this study are not the main issue of implementing CLIL in Chinese universities from students’ perspectives. In the process of interviews, the participants indicated that the factors affecting the pedagogical results mainly include teachers' charm, students' interests, curriculum arrangements, etc. The factor of textbooks is not within the scope of students' consideration, or they think that it is only an unremarkable factor. This may be related to the teaching methods in Chinese colleges and universities. In universities, students do not spend a lot of time previewing or reviewing, all relying on the lectures delivered by teachers. Meanwhile, a majority of teachers create their materials, at least from time to time, and have experience about how to structure and organize them, how to make them meaningful and practical at the same time, which leads to the low usage rate of textbooks wherever students are. Only when preparing for the final exam at the end of the semester will students read the textbook to review. In addition, some teachers will give the scope or content of the exam, without requiring students to read the whole textbook. Therefore, the textbook is an important factor for teachers rather than for students. However, creating CLIL materials is for many teachers a new issue. This is also true about novice teachers and pre-service teachers who have no or just a little experience with material development. In this sense, a lack of experience in teaching through L2 and a shortage of CLIL teachers, make the CLIL textbooks especially significant in the current educational contexts.

There is one more finding beyond the three research questions. Though CLIL is more universal in Chinese universities recently and popularized in many majors, China's CLIL is not the CLIL in the true sense, which is more like ESP or EMI. On the one hand, teachers use Chinese to explain knowledge with PPT in English. Thus, it can be seen that language teaching is not focused on. Teachers may not have enough knowledge of CLIL pedagogy and have not received formal training to be a CLIL teacher, so they simply integrate English into the curriculum. Due to the limited English proficiency of teachers, Chinese universities could hire foreign teachers who are the experts on majors or provide English training for these teachers. On the other hand, the exam also only tests whether students have a good command of content. Although the test paper is in English, it cannot reflect the students' English level comprehensively. Especially for students majoring in natural science, questions in English are mostly about calculation. The students majoring in social science answering questions in English to a certain extent can only reflect the English writing level.

This paper has shown the existing hindrances of textbooks that may prevent the implementation of CLIL in Chinese universities. However, it only worked with a small sample because of the developing CLIL pedagogy in Chinese universities. And this paper only applies qualitative data analysis, therefore bearing the limitation that is typical of this approach. Given the textbook hindrances, CLIL exhibits potential for development. When more and better resources for teaching and teacher development become available, as they probably will, CLIL may be implemented with greater success. Researches to search the hindrances except for textbooks of CLIL may provide more insights into how this approach can be adjusted to the Chinese context to make it more successful.

CONCLUSION

Firstly, the depth and difficulty of the content and language are not consistent with the level of students. Most of the textbooks lower the difficulty of content knowledge because of the integration of English. Secondly, the language of CLIL textbooks fails to make students realize the role of language for learning, of learning, and through learning. Finally, textbooks generally show a lack of cognitive, cultural, and communicative consideration. Despite the general awareness in society more broadly and in schools specifically of the commitment required to teach CLIL, the related teaching training is still not available across the country, which seems to be more crucial than the textbooks. Thus, textbooks even though filling the existing gap still play a subsidiary role for students, which, however, will be the main issue for teachers to design teaching materials. Since CLIL is implemented to support the aim of providing more and better education for students in response to the requirements of both language and subjects, it is high time to study other hindrances existing in the process of implementing CLIL.

The author has not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Ball P (2018). Innovations and challenges in CLIL materials design. Theory Into Practice 57(3):222-231.

Crossref

|

|

Banegas DL (2012). CLIL teacher development: Challenges and experiences. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning 5(1):46-56.

Crossref

|

|

|

Banegas DL (2014). An investigation into CLIL-related sections of EFL coursebooks: Issues of CLIL inclusion in the publishing market. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 17(3):345-359.

Crossref

|

|

|

Banegas DL (2017). Teacher developed materials for CLIL: Frameworks, sources, and activities. Asian EFL Journal 19(3):31-48.

|

|

|

Bonnet A (2012). Towards an evidence base for CLIL: How to integrate qualitative and quantitative as well as process, product and participant perspectives in CLIL research. International CLIL Research Journal 1(4):66-78.

|

|

|

Bovellan E (2014). Teachers' beliefs about learning and language as reflected in their views of teaching materials for Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). Jyväskylä Studies in humanities P 231.

|

|

|

Cai JG (2013a). Misunderstanding and Prejudice of ESP-the Major Barriers to the Development of ESP in China. Foreign Language Education 34(01):56-60.

|

|

|

Cai JG (2013b). Impact that Subject-based English and its teaching materials have on the development of ESP in mainland China. Foreign Language and Their Teaching 000(002):1-4.

|

|

|

Cai JG (2016). ESP in China: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Journal of University of Shanghai for Science and Technology 2:106-113.

|

|

|

Chang JY, Zhao YQ (2020). The concept and meaning of CLI- From CBI to CLI. Foreign Language Education P 5.

|

|

|

Cammarata L (2009). Negotiating curricular transitions: Foreign language teachers' learning experience with content-based instruction. Canadian Modern Language Review 65(4):559-585.

Crossref

|

|

|

Corbin J, Strauss A (2008). Strategies for qualitative data analysis. Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory P 3.

Crossref

|

|

|

Coyle D (2007). Content and language integrated learning: Towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10(5):543-562.

Crossref

|

|

|

Coyle D (2009). Promoting cultural diversity through intercultural understanding: A case study of CLIL teacher professional development at in-service and pre-service levels. In: Content and language integrated learning: Cultural diversity. Peter Lang pp. 105-124.

|

|

|

Coyle D, Hood P, Marsh D (2010). Content and language integrated learning. Ernst Klett Sprachen.

|

|

|

Cummins J (2008). BICS and CALP: Empirical and theoretical status of the distinction. Encyclopedia of Language and Education 2(2):71-83.

|

|

|

Del Pozo MÁM, Estébanez DR (2015). Textbooks for Content and Language Integrated Learning: policy, market and appropriate didactics? Foro de Educación 13(18):123-141.

Crossref

|

|

|

Gómez Ramos JL, Palazón Fernández JL, Lirio Castro J, Gómez-Barreto IM (2020). CLIL: graphic organisers and concept maps for noun identification within bilingual primary education natural science subject textbooks. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism pp. 1-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

Ioannou GS (2012). Reviewing the puzzle of CLIL. ELT Journal 66(4):495-504.

Crossref

|

|

|

Jiqing X (2019). A Review of the Development of Academic English in China in the Past Ten Years: Based on Comparison with Related International theses. Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages 42(3):64-72.

|

|

|

Kelly K (2014). Ingredients for successful CLIL. British Council, Teaching English. Retrieved 2nd September.

|

|

|

Liao LC (2019). A Study on the Curriculum Design and Implementation of EAP Courses in Chinese Universities. Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages P 3.

|

|

|

Llinares A, Evnitskaya N (2020). Classroom Interaction in CLIL Programs: Offering Opportunities or Fostering Inequalities? TESOL Quarterly.

Crossref

|

|

|

Medina BL (2016). Developing a CLIL textbook evaluation checklist. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning 9(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

Mehisto P, Asser H (2007). Stakeholder perspectives: CLIL programme management in Estonia. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10(5):683-701.

Crossref

|

|

|

Mehisto P (2012). Criteria for Producing CLIL Learning Material. Online Submission.

|

|

|

Meyer JW, Bromley P, Ramirez FO (2010). Human rights in social science textbooks: cross-national analyses, 1970-2008. Sociology of Education 83(2):111-134.

Crossref

|

|

|

Möller V (2017). Language acquisition in CLIL and non-CLIL settings: Learner corpus and experimental evidence on passive constructions (Vol. 80). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Crossref

|

|

|

Morton T (2013). Critically evaluating materials for CLIL: Practitioners' practices and perspectives. In Critical perspectives on language teaching materials. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 111-136.

Crossref

|

|

|

Morton T (2020). Cognitive discourse functions: A bridge between content, literacy and language for teaching and assessment in CLIL. CLIL. Journal of Innovation and Research in Plurilingual and Pluricultural Education 3(1):7-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

Nikula T, Dafouz E, Moore P, Smit U (2016). Conceptualising integration in CLIL and multilingual education. Multilingual Matters.

Crossref

|

|

|

Peyró MCR, Herrero EC, Llamas E (2020). Thinking skills in Primary Education: An Analysis of CLIL Textbooks in Spain. Porta Linguarum: Revista Internacional De Didáctica De Las Lenguas Extranjeras (33):183-200.

|

|

|

Tomlinson B (2012). Materials development. The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics pp. 1-7.

Crossref

|

|

|

Wen QF (2019). Foreign Language Teaching Theories in China in the Past 70 Years. Foreign Language in China. P.5

|

|

|

Xin JQ (2019). A Review of the Development of Academic English in China in the Past Ten Years: Based on Comparison with Related International theses. Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages 42(3):64-72.

|

|

|

Yang WH (2019a). Developing tertiary level clil learners'intercultural awareness with a self-produced coursebook integrating content and language. Journal of Teaching English for Specific and Academic Purposes pp. 329-347.

Crossref

|

|

|

Yang W (2019b). Evaluating contextualized content and language integrated learning materials at tertiary level. Latin American Journal of Content and Language Integrated Learning 11(2).

Crossref

|

|

|

Zhao YQ, Chang JY, Liu ZH (2020). Localization of Content and Language Integrated Instruction at the Universities in China. Foreign Languages in China P 5.

|