Judicial Protection of Intellectual Property Rights in a Digital Economy: Is There a Need for Change?

Published: Dec. 23, 2021

Latest article update: Sept. 21, 2023

Abstract

The paper looks at improving the judicial system in Russia facing the rapid technological change of modern society in which new relationships are largely associated with different areas of intellectual property. Today biotechnology, digital rights, computer programs and scientific research materials have become widely used in civil circulation and their intellectual property rights should be effectively protected. The paper discusses different issues of protecting intellectual rights provided for by the Civil Code of the Russian Federation, aimed at both suppressing and preventing their infringement, and assesses the statistical indicators of the courts. The practice of the Intellectual Property Rights Court and the Moscow City Court shows that specialization yields positive results. The selection of judges, their professional development including their distinctive competencies in addition to legal ones, also help to find effective ways of resolving intellectual property disputes. With the protection of intellectual property rights being of great concern not only in Russia, but also in most developed countries of the world, their experience has also been thoroughly analyzed. The paper suggests a possible way of improving the judicial system under the current circumstances. Certain changes in the judicial system and the creation of additional specialized intellectual property courts could help to ensure an affordable, legitimate and effective mechanism for resolving disputes related to the violation of intellectual property rights.

Keywords

Intellectual Property, court, exclusive right, judicial protection, judicial system, intellectual rights

Intellectual property in modern societies is a key driver of its economic, social and cultural development. The introduction of the new technologies creates complex networks of social relations. There are intense discussions underway about legal regulation of relations in the field of artificial intelligence; experimental legal acts are being adopted1. The transition from the traditional civil law relations, pivoted on the notions of a material object and obligation to the novel and much more complex relations based on such ideas as human impact on complex biological objects [Vasiliev S.A., et al, 2017: 71], digital technologies, etc., generates a previously unknown type of relations.

What is important is that these new relations, in one way or another, involve the use of intellectual property (IP). For instance, in telecommunication networks, items protected by copyright and related rights account for more than 80% of the content. Software programs for electronic computing machines are the main instrument used across the entire spectrum of disciplines by researchers today [Schwab K., 2018: 31-46]. So, ensuring effective protection for copyrighted items is a most important factor for the functioning of modern states.

Justice systems have to respond to the challenges brought about by the 4th technological revolution, and this is a challenge that any developed nation, no matter what its legal system is, has to face.

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights2 (hereinafter referred to as TRIPS) obligates its signatories to have “enforcement. .. available under their law so as to permit effective action against any act of infringement of intellectual property rights covered by this Agreement” At the same time, the TRIPS Agreement “does not create any obligation to put in place a judicial system for the enforcement of intellectual property rights distinct from that for the enforcement of law in general” (Art41(l and 5)).

However, although the international agreements do not obligate states to set up specialized courts for adjudicating disputes concerning intellectual property rights (IPR), a general trend to create such courts is on the rise in the vast majority of economically developed countries.

As the weight of IP in national economies grows, there is an increasingly stronger focus on the effectiveness of protection of copyright and related rights. There are certain items of intellectual property which cannot be protected by means of self-defense, such as, for instance, technological safeguards. Besides, due to their very nature most of copyrighted items and identifications (except manufacturing secrets) are intended to raise public awareness and promote goods, works and services on the market — in other words, their open use is the norm. In view of this, there is a growing demand for judicial protection of infringed or contested IPR, which rights, pursuant to Art. 1226 of the Civil Code of the RF, apply to protected identifications and results of intellectual activity.

The Russian legislation provides for a wide range of legal remedies in the field of IPR, intended to stop, as well as prevent, infringements thereof. Infringements of IPR in the Russian Federation are punishable under civil, criminal and administrative law. Depending on the character, degree of public danger, and consequences of an infringement, IP disputes can be treated as public or private law cases.

According to the court statistics3, the amount of court cases involving IP-related alleged criminal and administrative offenses has been declining in recent years. While in 2009 the courts heard 12,511 cases of administrative offenses covered by Art.7.12 of the Code of Administrative Offenses and involving infringements of copyright and related rights, inventors’ rights, and patent rights, in 2020 the courts heard 706 such cases; whereas in 2009 1,631 people received criminal convictions solely on account of infringements of IP and related rights, pursuant to Art. 146(2) of the RF’s Criminal Code, in 2020, only 155 people in the RF received criminal convictions in all proceedings related to infringements of IPR, including patents and trademarks (Art. 146, 147, 180 of the RF’s Criminal Code). The number of IP-related civil cases, meanwhile, is growing exponentially. According to the court statistics, the overall amount of civil cases handled both by general jurisdiction courts and arbitrazh courts have grown from 4,056 (in 2009) to 28,350 (in 2020). Rights holders seek not so much to punish the violators as put an end to their unlawful doings and receive a compensation for the infringements of IP rights. This article, therefore, is focused on civil disputes over breached or contested IP rights.

Some international agreements — for instance, Art.33 of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (Berne, Sept. 9,1886, hereinafter referred to as the Berne Convention), Art.28 of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (Paris, March 20, 1883), Art. 30 of the Rome Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organisations (Rome, Oct. 26, 1961) provide for an option of applying to an international court of law. This option, however, is reserved not for economic entities whose exclusive rights, covered by relevant international agreements, to copyrighted items and identifications have been breached but for member states who recognize such a court and only in relation to disputes over interpretation or application of a relevant convention, if these disputes cannot be settled by negotiation. There is no information available about any state applying to an international court during the period when the multi-lateral IP agreements providing for this option have been in place. The foundational multi-lateral international IP agreements — for instance, Art.5 of the Berne Convention — assert the primacy of national protection regimes: for instance, as per Art.5 of the Berne Convention, “the extent of protection [of IPR], as well as the means of redress afforded to the author to protect his rights, shall be governed exclusively by the laws of the country where protection is claimed,” that is the rights holder whose rights has been breached applies to the court of the country where the infringement took place and not to an international court.

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) runs an Arbitration and Mediation Center4, whose mission is to facilitate settlements of IP- and technology-related commercial disputes between private persons. This Center, however, is focused on mediation and the effectiveness of its decisions depends on the parties’ readiness to compromise, find mutually acceptable tradeoffs and continue their cooperation in the area of IP in the future.

The Eurasian economic space now has a new international court. Pursuant to the Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union (signed on May 29, 2014, in Astana)5 a Court of the EAEU was established. The court’s remit, established in Art. 39 of the Statute of the Court of the EAEU6, is limited to adjudicating disputes over the realization of the Treaty on the EAEU, international agreements within the EAEU, and decisions of the EAEU’s organs, to wit, the Eurasian Economic Commission (EEC). An economic entity may apply to the Court of the EAEU to contest an action (or inaction) of the EEC which has a direct bearing on the entity’s rights and lawful interests, if this action (inaction) has caused a breach of rights granted under international agreements within the EAEU, or to contest a decision of the EEC on the grounds that it allegedly breaches the entity’s rights and does not conform with international agreements within the EAEU. In other words, the new international court does not consider disputes over infringements of IPR involving economic entities from the EAEU’s member states.

In the RF cases involving the protection of infringed or contested IPR are heard by the courts of general jurisdiction or arbitrazh courts, depending on the subject matter jurisdiction.

The Arbitrazh Court for Intellectual Property Rights occupies a special place. The legal groundwork for the establishment and operation of this Court was laid in federal constitutional law No. 4-FKZ (Dec.6, 2011)7, which introduced amendments to federal constitutional law No. 1-FKZ (Apr.28, 1995) “On Arbitrazh Courts in the Russian Federation” and federal constitutional law No. 1-FKZ (Dec.31,1996) “On the Court System of the Russian Federation.”

The powers of the IP Court are set out in chapter IV. 1 of federal constitutional law No. 1-FKZ (Apr.28, 1995) “On Arbitration Courts in the Russian Federation” (with amendments) and its jurisdiction mostly covers industrial intellectual property; this Court is a specialized arbitrazh court which hears, in its capacity as the first-instance court and the court of cassation, cases concerning protection of IPR, as well as challenges of bylaws issued by federal executive bodies in relation to patent rights, breeders’ rights, rights to topographies of integrated circuits, manufacturing secrets (know-how), identifications of corporate entities, goods, works, services and enterprises, and rights to use copyrighted items in technology transfers [9. C. 80-84].

Other matters within the Court’s jurisdiction include disputes over the grant and termination of legal protection for results of intellectual activity and items equated to them such as identifications of corporate entities, goods, works, services and enterprises (except items protected by copyright and related rights, topographies of integrated circuits), as well as cases involving identification of patent holders; cases involving invalidation of patents for inventions, utility models and industrial designs or breeding patents; cases involving invalidation of decisions to grant a protection title for trademarks and appellations of origin and decisions to grant exclusive rights to such appellations, unless a federal law provides for different invalidation procedures; cases involving invalidation of decisions about early termination of a protection title for trademarks on account of their disuse.

The IP Court is authorized to resolve disputes challenging special bylaws, decisions and actions (inaction) of a federal executive organ responsible for IP and a federal executive organ responsible for breeding, and officers of such organs, as well as organs authorized by the RF’s government to review applications for patents for secret inventions. [Translator’s note: special bylaws — nenormativnye pravovye akty: acts targeting “a small, identifiable group for treatment that does not apply to all the members of a given class” (from a Wikipedia article on special legislation).] The Court hears cases involving challenges of the federal anti-monopoly organ’s decisions to recognize as unfair competition actions related to acquisition of an exclusive right to identifications of corporate entities, goods, works, services, and enterprises.

Beginning from 2016 the IP Court has been adjudicating disputes over normative acts, issued by federal executive organs, which contain explanations of legal norms and concern patent rights and breeders’ rights, rights to topographies of integrated circuits, rights to manufacturing secrets (know-how), rights to identifications of corporate entities, goods, works, and enterprises, and rights to use copyrighted items in technology transfers (para 1.1 was introduced by federal constitutional law No. 2-FKZ of February 15,2016).

Importantly, the mentioned types of disputes are considered by the IPR Court irrespective of the identity of the parties to the dispute, be it organizations, sole traders or private persons. In other words, the Court has a wider jurisdiction in relation to private persons than some arbitrazh courts.

But as for copyrighted items, the IPR Court hears them only in its capacity as the court of cassation.

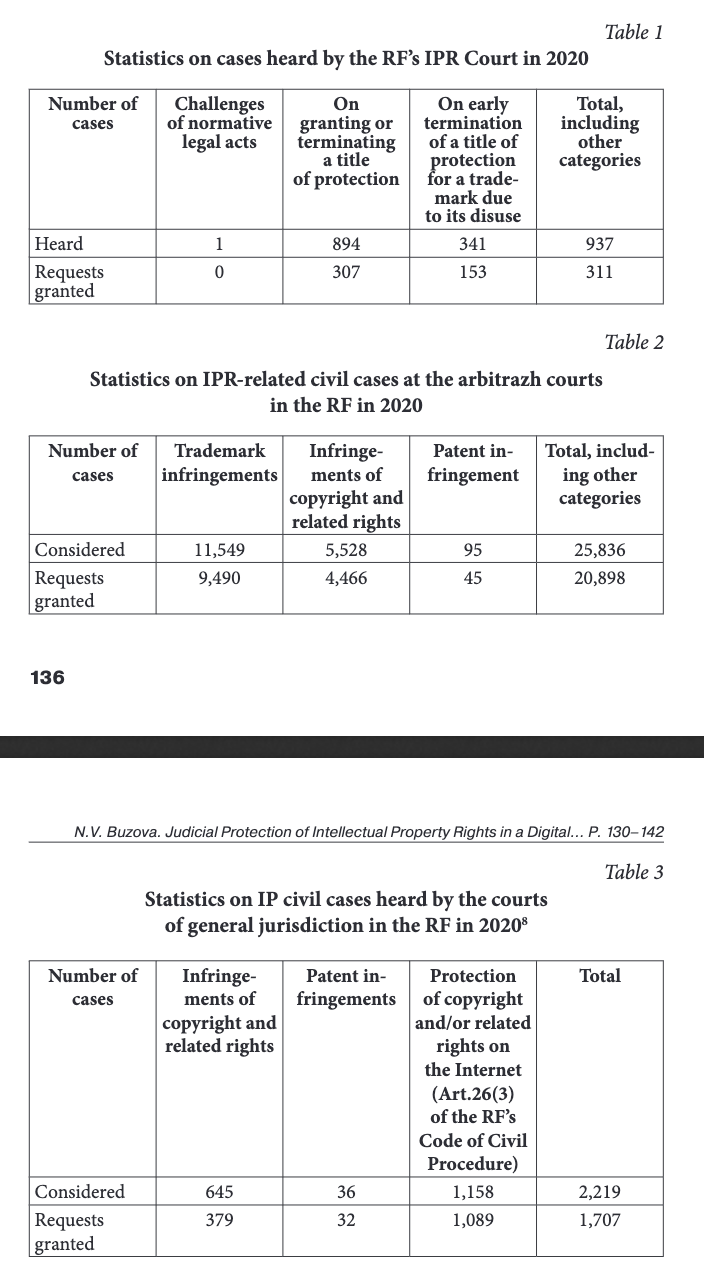

Court statistics for IP-related cases heard by different courts of the RF in 2020 is provided in Tables 1-3.

The court statistics shows that the arbitrazh courts account for a major portion (89%) of IPR civil cases in the RF. This is because many disputes arise from business and other similar transactions and from instances of unlawful trade in goods which breach exclusive rights to copyrighted items and identifications. Another thing to keep in mind is that the arbitrazh courts are the forum for disputes over identifications8 and protection of IPR the parties to which include collecting societies9. Besides, certain categories of cases — for instance, disputes over the authorship of inventions, utility models, industrial designs, breeding patents — are the purview of the IPR Court, which is a part of the system of arbitrazh courts.

The prospects of creating a specialized court for intellectual property — in particular, a patent court — were discussed yet in the Soviet Union, up until 1992-1993, when the RF adopted [Yeremenko V.I., 2012:22] the laws on trademarks, copyright, and patents; however, the idea to set up a specialized court was not realized at that time. Instead, the RF’s lawmakers authorized a quasi-judicial form of adjudication on matters concerning the issuance of protection titles and the grant of exclusive rights to certain items of intellectual property: the relevant provisions were contained in law on patents No. 3517-1 (Sept.23, 1992) and law of the RF No. 3520-1 (Sept.23,1992) “On Trademarks, Service Marks, and Appellations of Places of Origin of Goods.”

The growing numbers of cases involving contested IPR related to business transactions that the arbitrazh court had to handle (for instance, 3,482 cases in 2009 and 9,237 in 2013) was one of the factors spurring the establishment of a specialized IPR court in the RF. In order to reduce the length of proceedings and enhance their effectiveness in IPR cases [Korneev V.A. 2011:2], the IPR Court was established and started operating on July 3,2013.

Speaking about judicial protection of copyright and related rights, one should not forget to highlight the Moscow City Court — it handles, interalia, in its capacity as the first-instance court, civil cases which concern protection of copyright and related rights, except rights to photographs and items that were produced by means similar to photography and published in information and telecommunication networks, including the Internet, and in which this court has granted injunctive relief.

The changes in technologies and in communication and data storage devices used to reproduce works and copyrighted items call for new approaches to the protection of copyright and related rights. While at the time when the RF adopted its law No. 5351-1 (July 9,1993) “On Copyright and Related Rights” (hereinafter referred to as the Copyright Law) works and copyrighted items were reproduced with the use of VHS tapes, cassettes and disc records, the early 2000s saw the advent of optical storage devices for laser-beam systems, and from 2010 on, users of items protected by copyright and related rights, at first gradually and then en masse, have been using the information and telecommunication networks, including the Internet.

Under Art. 48 of the Copyright Law, phonorecords and copies of works whose manufacturing or distribution involved an infringement of copyright and related rights were deemed to be counterfeits. While the Copyright Law was in effect, the cassettes and discs were the foremost storage devices for works and items protected by related rights, so the focus was on police investigations aimed at discovering businesses manufacturing and selling counterfeit goods; the effective legal remedies, accordingly, consisted in shutting down facilities where counterfeit goods were manufactured and sold and in confiscating and destroying the equipment, materials and data storage devices used by infringers of copyright and related rights. Later the mentioned remedies against infringements of copyright and related rights became somewhat obsolete since the Internet became the space where the majority of infringements take place.

The first step taken to put an end to unlawful use of cinematic, televised and other audiovisual works was the adoption of Federal Law No. 187-FZ (July 2, 2013) “On Introducing Amendments to Certain Legal Acts of the RF With Respect To the Protection of Intellectual Property Rights in the Information and Telecommunication Networks,” often referred to as “the anti-piracy law,” which, beginning from Aug.l, 2013, authorized courts to issue injunctions to protect exclusive rights to audiovisual works on the Internet (Art. 144.1 of the RF’s Code of Civil Procedure). The law prescribes a procedure whereby courts can restrict access to films unlawfully posted on (or, to put it more accurately, unlawfully brought to general notice via) the Internet or remove such works pursuant to a rights holder’s complaint. Granting preliminary injunctive relief to protect copyright and related rights on the Internet is a responsibility of the Moscow City Court. The positive effect of the “anti-piracy law” has demonstrated the wisdom of the decision to expand the available remedies. The next step to put an end to unlawful use of copyrighted items on the Internet was to expand the “judicial mechanism” to apply to all objects of copyright and related rights which can be used on the Internet, except photographs (Federal Law No. 364-FZ (Nov.24, 2014) “On Introducing Amendments to the Federal Law ‘On Information, Information Technologies, and Protection of Information’ and to the Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation”). The law also authorizes courts to block access to those sites in the Internet on which copyrighted items were repeatedly unlawfully posted.

Despite the obvious positive effect from the conferral of additional powers on the Moscow City Court as provided by Art. 26 (3) of the RF’s Code of Civil Procedure, one cannot fail to notice an increase in the court’s caseload: from 446 cases in 2016 to 1,158 in 2020.

The RF is making a transition to digital economy — an environment which reduces the lengths of time needed to spread information, makes it possible to process large reams of data, and introduces new technologies — and this transition opens up new opportunities for using copyrighted items in digital formats. Given that copyrighted items and identifications are immaterial, a fair and comprehensive consideration of IPR cases, especially cases involving digital items, requires not only the knowledge of law but also expertise in other fields, including technical. At the same time, a weak protection of IPR in business matters can have a negative impact on the national economy’s attractiveness to investors and competitiveness. In view of this, it would seem advisable to continue the search for additional guarantees of fair justice — the system that would enable judges to quickly and effectively resolve the complex disputes in a continuously changing technological environment.

As has been noted earlier, the global trend is to have specialized courts adjudicate on IPR dispues, although different countries handle these matters differently, depending on the specifics of local legislative frameworks and economic and social development [de Werra J., 2016: 17]. The crucial question in the debate about the need for specialized IPR courts is enhancing the efficiency of the application of law in the area of IP. An analysis of the case law of the IPR Court and the Moscow City Court shows that the specialization brings good results although this is only the first stage. Creating a system that would produce a consistent case law without separation by the subject matter (an IP court) or by the parties and procedure (Moscow City Court) [7] would appreciably strengthen the effectiveness of protection of IPR in a rapidly changing technological landscape in the RF in the 21st century. According to different estimates, IP can account for 25-30% of the GDP and this share has a tendency to grow.

Developing a system of specialized IPR courts can probably promote the growth of effectiveness of the application of IPR law. So, what are the issues that need to be addressed when considering the prospect of creating of a single special court for IPR disputes?

It should be kept in mind that the mission of specialized IPR courts is to ensure an accessible, equitable and efficient mechanism for resolving disputes involving infringements of copyright and related rights — this system requires highly competent judges possessing, in addition to other things, a good knowledge of high technology.

The question of training and selecting judges is therefore one of the most important ones: it is essential for such judges to be competent in other fields besides law in general, and they should also be afforded opportunities of ongoing learning, which would keep them abreast of quickly occurring changes in IP law and national and international case law in this area.

The subject matter jurisdiction of these courts needs to be defined — for instance, in some jurisdictions IPR courts handle not only IP disputes but anti-monopoly cases as well. Procedures for appealing these courts’ decisions should be in place as well.

The current legislation, as it seems, allows for the establishment of specialized courts within the system of courts of general jurisdiction: this follows from Art.4 of federal constitutional law No. 1-FKZ (Dec.31, 1996) “On the Court System of the Russian Federation” (amended version) [Orlova V.V. et al. 2007:67].

For instance, the RF could establish specialized courts to resolve cases, in their capacity as the first-instance court, involving IPR and digital technologies. Such courts could be arranged along the same regional lines as the system of general jurisdiction courts of appeal and courts of cassation. Such specialized courts could each cover a group of regions.

Speaking about international experience, one should take notice of the district courts in Belgium specializing in IP disputes, as well as the High Courts of Korea, set up in Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Daejon, and Gwangju[Adjudicating Intellectual Property Disputes:2016]].

The IPR Court could become the forum for appeals against rulings of these courts, whereas the IP and digital technologies panel of the RF’s Supreme Court could function as the court of cassation.

References

- Adjudicating Intellectual Property Disputes. An ICC report on specialised IP jurisdictions worldwide. International Chamber of Commerce (2016). Available at: URL: http://www.iccbooks.ru/upload/iblock/402/4.pdf.

- Court for Intellectual Property Rights (2013). The History of Its Creation and the Prospects of Its Development. Moscow: INITS “PATENT,” 2013. 183 p. (In Russ.).

- The Court for Intellectual Property Rights and Its Place Among the Public Authorities in the Russian Federation (2015). Eds. Bliznets I .A., Novoselov L.A. Moscow: Prospect, 120 p. (In Russ.).

- International conventions on Copyright Law. Comment. Gavrilov E.P. (ed.). Moscow: Progress. 1982. 243 p. (In Russ.).

- Korneev V.A. (2011) What the Court for intellectual Property Rights Will Be Like? Patenty i litsenzii - Patents and Licensing, no. 1, pp. 2-6. (In Russ.).

- Lubimova E.V. (2019) Jurisdiction of the Court on Intellectual Rights. Ex jure, 3, pp. 29-42. (In Russ.).

- Novoselova L.A., Sergo A.G. (2017) On perspectives of using mediation for regulation of conflicts on intellectual property. University named after O.E. Kutafin Bulletin, 6, pp. 17-24. (In Russ.).

- Orlova V.V. et al. (2007) What Type of Patent Court Russia Should Have? Moscow: Patent, 77 p.

- Pirozhkov A.V. (2014) How the Courts Apply Federal Law No. 187-FZ (July 2, 2013) “On Introducing Amendments to Certain Legal Acts of the Russian Federation Concerning Protection of Intellectual Property Rights in the Information and Telecommunication Networks”. Rossiyskoe pravosudie - Russian Justice, no. 6 (98), pp. 62-77. (In Russ.).

- Popova S.S. (2013) Problems of the formation of the Court on Intellectual Rights in Russia. Imuzhestvennie otnoshenia vRossiiskoi Feder- atii - Property Relations in Russian Federation, no. 6(141), pp. 96-106. (In Russ.).

- Schwab K. (2018) The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Moscow: EKSMO, 208 p. (In Russ.).

- Sidorenko A.I. (2019) Court protection of intellectual rights in the digital era. Zhurnal rossiiskogo prava - Journal of Russian Law, no. 8, pp. 136-147. (In Russ.).

- Vasiliev S.A., Osavelyuk A.M., Burtsev, A.K., Suvorov G.N., Sarma- naev S.Kh., Shirokov A.Yu. (2019) Problems of Legal Regulation of Genome Diagnostics and Gene Editing in Humans in the Russian Federation. LexRussica, 6, pp. 71-79. (In Russ.).

- de Werra J. (2916) Specialized Intellectual Property Court — Issues and Challenges. Second Issue, Global Perspectives for the Intellectual Property System, no. 2. Available at: URL: https://www.ictsd.org/sites/default/files/research/Specialised%20lntellectual%20Property%20 Courts%20-%20lssues%20and%20Challenges_0.pdf.

- Yeremenko V I. (2012) On Establishing a Court for Intellectual Property Rights in the Russian Federation. Zakonodatel’stvo i ekonomika - Legislation and Economy, 2012, no. 8, pp. 9-22. (In Russ.).