The contribution of Freud’s structural model of the mind to the understanding of the personality of Ambrosio, the main character of the Gothic novel, The Monk

Published: Nov. 30, 2021

Latest article update: Aug. 21, 2022

Abstract

Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical theories may be helpful to the analysis of literary works since the contribution of psychoanalysis to literature provides useful interpretative insights. Reading novels, poems and other compositions through the lens of psychoanalysis gives the opportunity to analyse and evaluate these works in their genesis and functioning. The Gothic novel provides many elements such as fear, duplicity, abuse of power and seduction that can be explained according to a Freudian model of literary criticism. In this paper, the personality of Ambrosio, the main character of the Gothic novel The Monk, is investigated with reference to Freud theories concerning the structural or tripartite structure of the mind which conceives the psyche as divided into three parts: Id, Ego and Super-ego. For this purpose, a critical analysis of the text of the novel has been made so to identify all those elements (behaviour, attitudes, emotional reactions, thoughts and utterances) connected to Ambrosio which may illustrate the hidden aspects of his personality and, moreover, explain the reasons of his moral decline.

Keywords

Id, The Monk, Gothic novel., Freud, Super-ego, Ego

INTRODUCTION

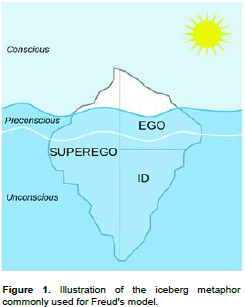

Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytical theories can be used with reference to the analysis of literary works. Reading novels, poems, and other compositions through the lens of psychoanalysis gives the opportunity to analyse and evaluate the works of literature in their genesis and presentation. Freudian doctrine can be considered as a reading tool that allows the investigation of the enigmatic areas of human experience and, therefore, its main contribution to literature is related to the discovery of hidden aspects of the text, of the writer and of the reader as well. This essay consists in a close reading of the Gothic novel The Monk and in a deep analysis of the main character, Ambrosio, according to the structural or tripartite model of mind as theorised by Sigmund Freud. In short, this model considers the division of the psyche into three parts, Id, Ego, and Super-ego, along with the distinction of conscious, unconscious, and preconscious (Akhtar, 2009). The Id represents the instinctual life and is completely unconscious, the Ego is the part that is related to perception, emotions and will and is primary conscious while the Super-ego refers to morality, values and principles of conduct and is mainly unconscious. Freud’s structural model is an evolution of his previous topographical theorization that describes three levels of the mind which are the conscious mind, the preconscious and the unconscious (Freud, 1923). Figure 1 shows the graphic illustration of Freud’s model of the human mind. According to Freud, these three parts interact in a continuing way during the life of each individual and their relationship can be considered harmonious and peaceful when there is a good equilibrium among the parts. However, most of the time, their correspondence can be considered rather disagreeable especially when Id, Ego and Super-ego are in discordance. As a matter of fact, there is an ongoing competition which may explain the psychological conflicts of the human mind and which is also responsible for the instability of an individual’s mental equilibrium. A critical analysis of The Monk has been performed in order to detect all those elements such as behaviour, attitudes, emotional reactions, thoughts and speech that refer to Ambrosio and that may explain the overt and hidden aspects of his personality. This type of approach to the novel may increase the understanding of the psychological changes that occur to this character and justify his progressive decline into perversion, his macabre and evil behaviour and his moral collapse.

ANALYSIS OF THE CHARACTER OF AMBROSIO

Ambrosio is represented as a person whose psychological strength and moral solidity is continually under threat either by external factors such as the seduction of Rosario/Mathilda or by intrinsic aspects of his personality. In chapter two, the first representation of Ambrosio is that of a person who emphasises his personal virtues:

‘Who, thought me, who but myself has passed the ordeal of youth, yet sees no single stain upon his conscience? … I see no one but myself possessing such resolution’ (Lewis, 2009:31).

In this passage, the Ego that is apparently reflecting on his own situation is unconsciously attributing to himself a moral superiority (‘splendid vision of aggrandisement’). In this self-attribution the Ego is attempting to defend himself against the Super-ego who is very much concerned about the temptations of the world and of the risk of losing one’s position in society as it emerges in the following lines:

‘Yet hold! May I not be tempted from those paths which till now I have pursued without one moment’s wandering?

Am I not a man, whose nature is frail, and prone to error?’ (31-32).

Furthermore, in Ambrosio’s soliloquy with the painting of Virgin, the instinctual side of the Id emerges in the form of a libidinal attraction for the: ‘Divine eyes? …the blush of that cheeks… those golden ringlets… the snowy bosom’. (32) This sexual desire is promptly banished by the Super-Ego in the following lines at the same page: ‘Fool that I am! ... Away impure ideas! ... Temptation, did I say? To me it would be by none’. It is clear here that the moral conscience is intervening to restore the previous equilibrium between the three parts of the mind: ‘fear not, Ambrosio! Take confidence in the strength of your virtue … you are superior’.

Interesting at this point is the use of the terms ‘reverie’ and ‘delirium’ employed by the author to describe the mental condition of the character. Reverie is a synonym of daydreaming, a mental activity which Freud conceived as the fulfilment of conscious wishes and as a way to better comprehend the conflicts of the human psyche (Freud, 1900). As a matter of fact, Ambrosio’s reverie may be considered as a representation of his phantasies. Mental images of omnipotence and lust, secret passions and desires are here revealed to the reader in order to create a clear and initial picture of the character’s true disposition. Moreover, the ‘delirium’ to which Lewis refers (‘With difficulty did the abbot awake from his delirium’) is a medical condition which can be defined essentially as a temporary alteration of the mental faculties and is characterised by confused thoughts and a diminished perception of the external surrounding. Indeed, Ambrosio’s thoughts are disoriented as he shifts from ideas of grandeur to mental images of weakness (‘am I not a man, whose nature is frail, and prone to error?’) and then he releases the phantasy of a sexual intercourse with an inanimate object, the painting of the Madonna. Only a real and external event will bring him back to reality: the knocking at the door and the appearance of Rosario on the scene. The meeting with the feigned novice and sorceress is an important point of the plot since it will encourage the abbot to realize his sexual appetites and then to put pressure on the complete release of psychic energy from the Id.

The discovery of a woman in the convent, the temptations, the initial shock and, most of all, the risk of losing his station as a respectful member of the Church have gradually activated the self-critical Super-ego who, in turn, induced the Ego to reject any form of relation with the cause of disturbance: ‘By degrees he recovered from his confusion … I will not expose myself to so dangerous a temptation’; ‘You have heard my decision, and it must be obeyed … you must from hence!’ (48) These words uttered by Ambrosio may appear as a decisive and conclusive remark but at night, during sleep, the defensive abilities of the Ego generally lose their power so that the Id regains its energy. The restless sleep and the oneiric activity described by the author illustrate the hidden phantasies of the abbot: ‘during his sleep his inflamed imagination had presented him none but the most voluptuous object … such where the scenes on which his thoughts were employed while sleeping’ (51-52). The description of these dreams confirms the theorisation made by Freud concerning the satisfaction that wishes may unconsciously receive during sleep (Watson, 1916) but in Ambrosio’s case this realisation is troubled by the sanctions of the Super-ego, which is not permissive.

At this stage, the struggle between the three parts of Ambrosio’s mind has found a temporary truce with the victory of the strong impulses coming from the Id which justify the behaviour and the final decision of the abbot to renounce to his vow of celibacy. Unfortunately, the inner conflict will not come to an end, and it is possible to detect in chapter six of the novel that Ambrosio’s conscience, determination, and mental tranquillity have changed: ‘His brain was bewildered, and presented a confused chaos of remorse, voluptuousness, inquietude and fear. He looked back with regret to that peace of soul, that security of virtue, which till then had been his portion’. (167) Furthermore, his Ego is showing signs of weakness as his volition and decision-taking will be guided and manipulated by his mistress. Interesting is the analysis of the conduct of the two partners whose minds face the present situation in different ways except for the seeking of sexual pleasure (Id) for which they seem to understand each other very well. Ambrosio’s moral sense is evidently stronger than Matilda’s conscience. His first emotional reaction was so intense that he had considered his concession to pleasure a crime and, most of all, the responsibility of the improper conduct is attributed exclusively to Matilda: ‘Dangerous woman ... Into what abyss of misery have you plunged me!’, and again: ‘Wretched Matilda, you have destroyed my quiet for ever!’ (165) it seems here that the Ego is experiencing the threat of the Super-ego with the additional awareness that one’s situation is possibly changing or at risk of being altered if the secret affair is disclosed. It is at this point that Matilda’s apparently stronger Ego and less severe moral sense will intervene to guide the behaviour of the friar who will pursue in seeking pleasure: ‘The abbot possessed his mistress in tranquillity, and perceiving his frailty unsuspected, abandoned himself to his passions in full security’. (173) The initial submissive and docile disposition of Matilda will turn into a dominant and imposing attitude that is a motive of concern for Ambrosio whose mind will be subjugated: ‘Now she assumed a sort of courage and manliness in her manners and discourse … She spoke no longer to insinuate, but to command …. Every moment convinced him of the astonishing power of her mind’. (171) What should be most concerning here is not the deviation of the lady’s behaviour whose disposition is indecent, but the profound change of the abbot’s personality whose will is not any more under his command but under the influence of factors of which he is mainly unaware. These factors are represented by the control exerted on him by another person and, most importantly, by the prevarication of the instinctive side which had eventually been repressed for too much time: ‘but it was clear that he was led to her arms, not by love, but the cravings of brutal appetite’. (174) Matilda is actually the temptation, the instigator of sexual desire, the personification of the Madonna that was so much an object of Ambrosio’s secret autoerotic phantasies but, in the end, she represents those demoniac and evil forces that are responsible for the excesses of passions, the manifestation of aggressiveness and the final decline of this man’s conduct. These aspects clearly explain the typical anti-Catholic tendency of gothic fiction as well as confirming the presence of gothic motifs in the novel which are represented by the supernatural and evil forces, the scenes that evoke horror (rape, murder, incest) and yet the sexual perversion and deviant behaviour of the monk (Botting, 2014) For all these reasons, the first publication of the novel caused a public reaction of disgust for the immorality and obscenity of the story.

In chapter six, Lewis provides interesting insights into the deterioration of the personality of Ambrosio, who appears as a person with a False Self. The concept of False Self was first conceived by Donald Winnicott who described the situation in which a child who built a defensive and factitious personality because of his relationship with a mother whose nurturing and protective abilities were inadequate or absent (Daehnert, 1988). Ambrosio had been deprived of maternal or parental affection at an early age and was subsequently raised by the Capuchins for most of his life. His initial disposition, the ‘warrior’s heart’, which was characterised by intelligence, bravery and sensibility, was repressed during his upbringing in the convent: ‘Instead of universal benevolence, he adopted a selfish partiality for his own particular establishment …. No wonders that his imagination …. Should have rendered his character timid and apprehensive ….. He was suffered to be proud, vain, ambitious, and disdainful …. He was implacable when offended and cruel in his revenge’ (175). From this description, it is possible to assume that the abbot’s personality was unnatural and rather forged by the environment in which he grew up. The artificiality of his nature is evident in his incapacity to cope or deal with the repressed impulses and desires of the unconscious. The Super-ego had been generated on the grounds of on excessive morality and on ideals of perfectionism while the Ego was trained to strongly repress the Id in its expression: ‘and in order to break his natural spirit, the monks terrified his young mind by placing before him all the horrors …. and threatened him at the slightest fault with eternal perdition’. (175) In the end, thanks to his religious fostering and apprenticeship, Ambrosio develops a weak and ingenuine Ego, an excessively repressed Id, a ferocious and severe Super-ego which eventually reached an equilibrium by creating of a false identity or self: ‘At such times the contest for superiority between his real and acquired character was striking and unaccountable to those acquainted with his original disposition’ (175). The connection between Ambrosio’ personality and the problem of the double, or Doppelgänger, in Gothic fiction becomes clear at this point of the analysis. The monk does not possess a stable, firm, and balanced disposition as described in the beginning of the novel, but his true nature gradually appears as brutal, ruthless, and inhuman. The praised and worshipped representative of the Church, the emblem of moral rectitude and good conduct turns out to be the opposite or rather the agent of evil and criminal deeds. One might argue here that in the same person there is the coexistence of a Self and a non-Self (or the ‘Other’), a circumstance that can be explained in terms of the prevarication of hidden desires and repressed impulses from the Id rather that the external influence of supernatural forces (Živkovi?, 2000). Indeed, it will be the friar’s decision to accept the invitation of Mathilda and then to embrace the magic and dark powers that will lead him to his resolution as shown in the mirror scene: ‘Ambrosio could bear no more: his desires were worked up to frenzy. ‘I yield!’ he cried, dashing the mirror upon the ground: “Matilda, I follow you! Do with me what you will!”’ (200). The expression of sexual and aggressive drives reaches its apex from this point onwards. The Ego has lost its primitive structure and is now functioning under the guide of evil entities, the Super-ego is not as vigorous and active as before and the Id, the location of the most unpredictable and volatile impulses, gets the complete control of Ambrosio’s personality. His behaviour becomes therefore similar to that of a beast that wants to consume and devour its prey as illustrated during his first sexual approach to Antonia when he misinterprets the feelings of the young girl: ‘At this frank avowal Ambrosio no longer possessed himself, wild with desire, … he fastened his lips greedily upon hers, sucked in her pure delicious breath, violated with his bold hand the treasures of her bosom, and wound around him her soft and yielding limbs’ (193). The words used in this passage, wild, sucked, fastened, violated, and wound give a clear picture of the impetus and violence of the monk’s conduct.

The final decline of Ambrosio’s personality is well described by Lewis in the following passage: ‘with one hand he grasped Elvira’s throat so as to prevent her continuing her clamour … with all his strength, endeavoured to put an end to her existence. He succeeded but too well’. Apart from releasing his sexual drives, the monk accomplished the most horrible of crimes, the assassination of an innocent person expression of a complete subjugation to the wishes of the Id.

What remains questionable is the analysis of the motives of the transformation of an apparently mild and pious man into a perpetrator of such blasphemous and sacrilegious deeds. The anti-Catholicism position of Gothic literature may shed some light on the behaviour of the abbot (?owczanin, 2013). Firstly, the repression of sexuality imposed by Catholicism to all those who decide to embrace religious life may be considered as a valid motive in Ambrosio’s case but likely not the only one. Secondly, the seclusion from the external world and the lack of social interactions with people, especially women, may justify the incapacity to create sincere and genuine relationships with the other sex. Thirdly, the absence in childhood of a stable and lasting connection with a maternal figure; this factor may have contributed to the emergence of perverted phantasies of a physical contact with the other sex, an intimacy that never occurred in the monk’s early life. Fourthly, the social position of women in a catholic country where they are conceived as innocent and pure icons on one side (for example, the character of Antonia) and on the other side: the embodiment of devilish and fierce temptations such as the role of Matilda in the novel.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, M.G. Lewis describes the progressive degeneration of the personality of Ambrosio, a person who is initially depicted as one of the most worshipped and honourable representative of the Holy Catholic Church while, at the end of the novel, he turns into the most miserable and deplorable human being to such a degree that even the daemon rejects him (‘What? … Dare you still implore the Eternal’s mercy?’) (323). The motives that explain this decline are related to all the aspects illustrated so far, particularly to the weaknesses of a man’s personality structure. In addition, faith and morality are not the monk’s authentic points of strength but, in this case, religion can be considered as a form of consolation for a person who had not received that much from life in terms of affection and wealth. As a matter of fact, Ambrosio’s strong devotion and attachment to a pious life may represent a way to overcome feelings of inferiority and impotence (Freud, 1930) which belong to his true nature. In a similar way, his criminal and immoral behaviour and turning to the supernatural and evil forces may be the attempt of a deviant mind to deal with a chronic sense of helplessness. In the end, the monk reaches a point of no return, there is no possibility to redeem or to restore his previous situation, and, eventually, death is the only solution to his psychological breakdown.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

Akhtar S (2009). Comprehensive Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. | |

Botting F (2014). Gothic writing in the 1790s. In: Gothic Chaps 4:69-73. Routledge. | |

Daehnert C (1998). The false self as a means of disidentification: A psychoanalytic case study. Contemporary Psychoanalysis 34(2):251-271. | |

Freud S (1900). The dream as wish-fulfilment. In: The interpretation of dreams, Chapter. 3, pp. 43-48. | |

Freud S (1923). The Ego and the Id. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923-1925): The Ego and the Id and Other Works, 1-66. | |

Freud S (1930). Civilization and its Discontents. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XXI (1927-1931): The Future of an Illusion, Civilization and its Discontents, and Other Works, pp. 57-146. | |

Lewis M (2009) The Monk. Wordsworth Editions. | |

?owczanin A (2013). Death and the woman in MG Lewis's The Monk. Kwartalnik Neofilologiczny. | |

Watson JB (1916). The psychology of wish fulfilment. | |

Živkovi? M (2000) The double as the "unseen" of culture: toward a definition of Doppelganger. University of NIŠ The Scientific Journal Facta Universitatis Series: Facta Universitatis-Linguistics and Literature 2(7):121-128. | |