Understanding Immobility: Moving Beyond the Mobility Bias in Migration Studies

Published: March 31, 2019

Latest article update: Oct. 18, 2022

Abstract

This article suggests that there is a mobility bias in migration research: by focusing on the “drivers” of migration — the forces that lead to the initiation and perpetuation of migration flows — migration theories neglect the countervailing structural and personal forces that restrict or resist these drivers and lead to different immobility outcomes. To advance a research agenda on immobility, it offers a definition of immobility, further develops the aspiration-capability framework as an analytical tool for exploring the determinants of different forms of (im)mobility, synthesizes decades of interdisciplinary research to help explain why people do not migrate or desire to migrate, and considers future directions for further qualitative and quantitative research on immobility.

Keywords

Understanding immobility, Migration Studies, Mobility Bias

Introduction

Migration studies suffers from a mobility bias. The accusation may seem strange, given that mobility is the very subject the field aims to understand. Yet this article will argue that a systematic neglect of the causes and consequences of immobility hinders attempts to explain why, when, and how people migrate. International migrants have long composed only 2 to 4 percent of the world’s population (Zlotnik 1999; UN 2015), and rough estimates of internal migration suggest an additional 12 percent (Bell and Charles-Edwards 2013). Still, despite the oft-cited statistic that one in seven people are on the move (IOM 2015), few scholars ask why, in our age of globalization, six out of seven are not.

This mobility bias has consequences. In the realm of migration theory, it leads scholars to focus on migration’s “drivers” and to overlook the countervailing forces that restrict or resist them. As a result, existing theoretical frameworks and the empirical research they inspire fail to explain why the size of migration flows are, despite “great disparities in wealth, power, and population, . . . really rather modest” (Massey et al. 1999, 7; see also Hammar and Tamas 1997). In their seminal review of migration theories, Massey et al. (1999) conclude that any satisfactory theoretical account of international migration must contain four basic elements: the structural forces that promote emigration from origin areas, the structural forces that attract immigrants into destination areas, the social and economic structures that connect origin and destination areas, and the aspirations and motivations of those people who respond to these structural forces by migrating (281). A core argument of this article is that these elements alone are insufficient to explain real-world migration trends. The structural forces that constrain or resist migration in and between origin and destination areas, as well as the aspirations of actors who respond to these same forces by staying, must also be included.

To meaningfully incorporate immobility into migration research, immobility should be approached as a process with determinants of its own, which is to say as complex, dynamic, and, as Hjälm argues, “diverse and ongoing a phenomenon as moving” (2014, 578–79; see also Gray 2011; Gaibazzi 2010; Mata-Codesal 2015; Coulter, van Ham, and Findlay 2016; Preece 2018). The challenges associated with defining immobility mirror those that arise when studying migration. Migration can refer to many forms of spatial mobility. Some of the earliest migration scholarship examined internal migration (Ravenstein 1885), while contemporary scholars focus mostly on international migration (Castles, De Haas, and Miller 2014). Similarly, immobility may be defined relative to particular spatial and temporal frames: residential, internal, or international; annual, throughout the life course, or across generations. Inspired by Hägerstrand’s definition of migration as changes in one’s “center of gravity” (1957, 27), I define immobility as spatial continuity in an individual’s center of gravity over a period of time. Immobility is never absolute, as indeed all people move in their everyday lives — to school, to work, to the market. Thus, just as migration must be distinguished from everyday forms of movement, most often by a change in residence for a certain length of time, immobility may be distinguished by continuity in one’s center of gravity, or place of residence, relative to spatial and temporal frames.

Studying spatial continuity — staying in place — is challenging from a methodological perspective. Existing census or other longitudinal datasets are often not detailed enough to track staying behavior across the life course, and surveys of migration aspirations rarely treat the desire to stay directly (Carling and Schewel 2018). A more fundamental challenge is that determinants of change are generally given priority within the social sciences, and human agency is often conflated with human action — in this context, movement (see Emirbayer and Mische 1998). Yet a burgeoning immobility literature suggests that for many non-migrants, staying also reflects and requires agency; it is a conscious choice that is renegotiated and repeated throughout the life course (Gray 2011; Hjälm 2014; Stockdale and Haartsen 2018; Mata-Codesal 2018). After all, migration is only one possible response to changing life circumstances (Malmberg 1997).

However, even for “migrant populations,” periods of immobility raise important research questions. Too often, someone who leaves home once becomes a “migrant” for life; even his or her children are cast as second- and third-generation immigrants. Mobility washes over the narratives we tell about “migrant” lives, and the moments in which further movement is renegotiated, resisted, or restrained – when migrants are not migrating – are lost. Why some people stay in their home place for their entire lives is an important research question. Equally interesting is why some people fail to complete the migration process they anticipated. How, for example, do we conceptualize migrants who become “stuck” in transit, immobilized before they reach their aspired destination (Hyndman and Giles 2011; Collyer, Duvell, and De Haas 2012; Van Hear 2014)? Why do some migrants stay at their destination when others return home or move on (Halfacree and Rivera 2012)? What forms of (im)mobility characterize migrants’ lives after return (Mata-Codesal 2015)?

To advance a research agenda on immobility1 (A note on terminology: various terms have been used to refer to those who do not migrate,each carrying connotations and implied relationships to mobility: non-migrants, stayers, the left-behind, the immobile (Jo ́ nsson 2011). All are potentially valid, depending on the researchers’ emphases and context. The most common, “non-migrants,” is also the most neutral yet is limited by defining those who stay only by what they are not. “Stayers,” on the other hand, denotes more agency to non-migrants (Hja ̈lm 2014). “Left-behind” has a more normative connotation and often limits studies of immobility to households with a migrantelse where (Toyota, Yeoh, and Nguyen 2007). This article uses the termim mobility becauseof its flexibility: it is the counterpart to movement but more than simply “not-movement.”Immobility may occur relative to a range of administrative boundaries (local, regional,national) and allows for the analysis of staying behavior across the spectrum of “forced” to“voluntary.” Immobility may be the undesired outcome of constraints on movement, the fulfillment of the desire to stay, or something in between. Finally, I also use the terms preference,aspiration, and desire interchangeably; although there are nuanced differences between these terms, for the purpose of my argument, I use them to refer to the overallperception that one alternative (here, migration or staying) is better than another), this article illustrates the value of integrating immobility into migration studies and offers concrete theoretical and methodological suggestions for how to do so. It proceeds as follows: after clarifying what I mean by “mobility bias,” I propose a revised version of the aspiration-capability framework as an analytical tool for exploring the determinants of different forms of (im)mobility. This framework suggests approaching immobility from two perspectives: as a result of structural constraints on the capability to migrate and/or as a reflection of the aspiration to stay. Because immobility preferences receive less attention in migration research than do migration constraints, I then review a range of potential explanations for the aspiration to stay, highlighting the often-overlooked “retain” and “repel” factors and economic “irrationality” that also shape migration decision-making. I show how a focus on staying preferences directs attention to the non-economic considerations often left out of migration theories, particularly aspirations related to family or community that may vary by gender or social group. Finally, I consider how further empirical research on immobility could proceed. I suggest a definition of immobility that complements definitions of migration, consider the opportunities and challenges associated with various quantitative and qualitative designs, and pose questions for further research.

The Mobility Bias

The phrase “mobility bias” describes an overconcentration of theoretical and empirical attention on the determinants and consequences of mobility and, by extension, the concomitant neglect of immobility — a combination that distorts understandings of the social forces shaping (im)mobility dynamics. Scholars have long noted the detrimental absence of immobility in migration research. In 1981, De Jong and Fawcett argued that across disciplinary approaches to migration, the inability to explain why people move was “attributable in a large measure to a failure to ask the question, ‘Why do people not move?’” (43). Arango echoed this sentiment in his 2000 review of migration theory, suggesting that “theories of migration should not only look to mobility but also to immobility, not only to centrifugal forces but also to centripetal ones” (293). The edited volumes by De Jong and Gardner (1981) and Hammar et al. (1997) presented extensive interdisciplinary inquiries into the question, “Why do people not migrate?” but relatively few subsequently built on the insights offered therein. As Stockdale and Haartsen (2018) note, despite the well-established call to focus on immobility, few studies examine actual stayers and staying processes; and when they do, it is often in negative terms (i.e., those “left-behind” or “stuck”). The need for “robust theoretical frameworks and theories specific to the study of immobility and staying,” thus, remains acute (ibid., 6).

One reason immobility lies at the periphery of migration studies is the dominance of sedentary and nomadic metanarratives about the nature of people and society, neither of which suggest immobility as a worthwhile research subject. Sedentary metanarratives presume the “rootedness of people” as the natural and desirable state of affairs (Malkki 1992, 31; Bakewell 2008). Many strands of social theory, particularly functionalist and neoclassical perspectives, present equilibrium and stasis as the default state of people and social systems (Massey et al. 1993; Sheller and Urry 2006; De Haas 2010). From this perspective, immobility is normal, and migration is the “aberration” requiring explanation and investigation. As a result, migration researchers often “relegat[e] stayers to the background of social analysis and tak[e] their settled lives for granted” (Gaibazzi 2010, 3).

To counter sedentary perspectives in the social sciences, a novel strand of theory and research, heralded as the “mobility turn” in the social sciences, introduced a way of seeing the world that put mobility and flux at the center (Urry 2000; Sheller and Urry 2006). Although this perspective recognized that mobility requires “moorings” (Urry 2003; Adey 2006), the research agenda it set in motion became so focused on developing a “nomadic metaphysics” and “mobile methods” that it tended to replace “one positively loaded pole, sedentarism…by its opposite, nomadism” (Faist 2013, 1644). Equally important, nomadism leaves little room for immobility, since, as Cresswell notes, “when seen through the lens of a nomadic metaphysics, everything is in motion, and stability is illusory” (2006, 55). Thus, the extremes of both paradigms, the sedentary and the nomadic, reinforce a mobility bias in migration research by neglecting immobility as a valid research category.

Nevertheless, some scholars began using immobility as a lens to challenge the grand narrative of hypermobility, flux, and fluidity associated with modernity. Bauman (1998), for example, argued that the ability to migrate has become a coveted and powerful stratifying factor in contemporary society. Carling (2002) highlights that far more people would like to migrate than actually do and suggests that rather than an “Age of Migration” (Castles, De Haas, and Miller 2014), our times are better characterized as an age of “involuntary immobility.” Rather than dissolving borders, Shamir (2005) urged that globalization should be analyzed as “processes of closure, entrapment, and containment” (199; see also Turner 2007). As these perspectives highlight, the “regimes of mobility” that normalize the movement of the privileged simultaneously enforce the immobility of others (Glick Schiller and Salazar 2013; see also Massey 1994).

The “mobility regimes” approach advances research into immobility; however, its framing of immobility remains one-sided. To dampen exuberance for the “new mobilities” studies, researchers often focus on the ways in which “the poor and disempowered find themselves contained” (Glick Schiller and Salazar 2013, 4). From this perspective, immobility is predominantly cast as involuntary, a result of constraints on the freedom and desire to move, a “hallmark of disadvantage and exclusion” (Faist 2013, 1644). Yet just as mobility “is a highly differentiated activity where many different people move in many different ways” (Adey 2006, 83), so too is immobility. Mata-Codesal’s (2015) research on “different ways of staying put” in rural Ecuador shows that immobility is “involuntary” for some but “desirable” for many others (2286). Additionally, Cohen (2002) differentiates three types of non-migrant households in Oaxaca, Mexico (the marginal, the average, and the successful) to demonstrate how access to socioeconomic resources influences decisions to stay. Some stay because they cannot leave; the “marginal” households cannot cover their daily expenses, much less afford an international migration endeavor. Others stay because they prefer to do so; “successful” households thrive in place, with relatively abundant land, economic prospects, and social status. Doreen Massey (1994) argued that different individuals and social groups have distinct relationships to mobility in the modern world: “some are more in charge of it than others; some initiate flows and movement; some are more on the receiving end of it than others; some are effectively imprisoned by it” (149). This statement rings equally true for immobility: some are more “in charge” of their immobility; others feel imprisoned by it.

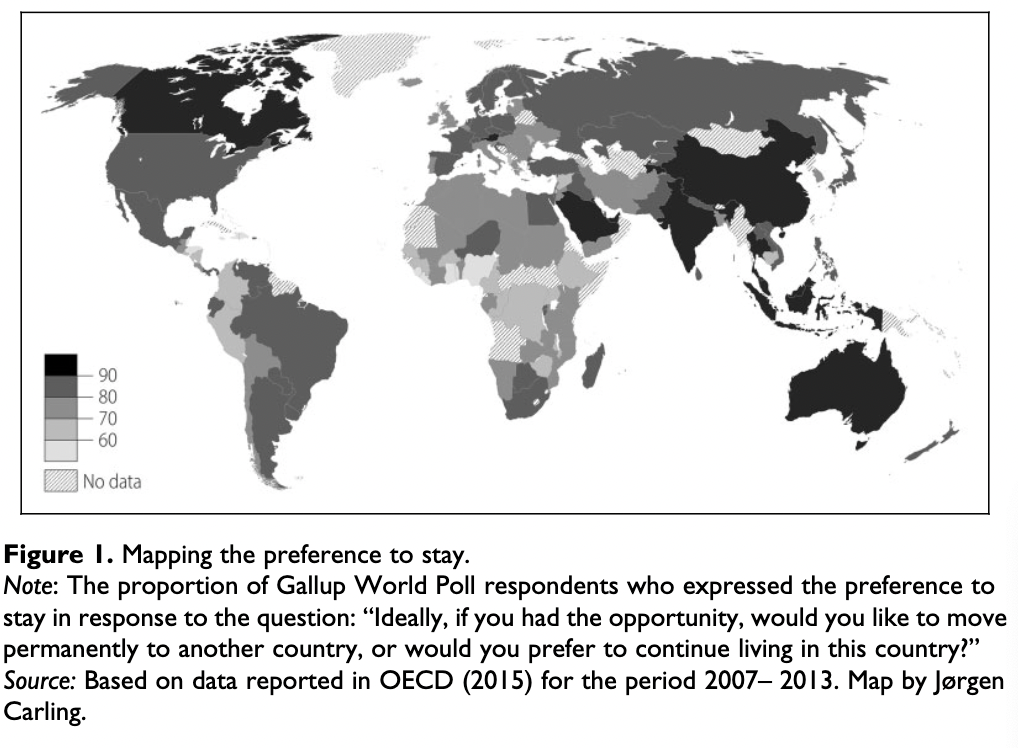

Advancing research into different forms of immobility requires examining not only what constrains mobility but also why people do not want to migrate. From a global perspective, the preference to stay within one’s country is far more common than the aspiration to migrate. Even in areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa, where some of the highest rates of migration aspirations exist, over half of adults (51%) do not desire to move even temporarily to another country (Esipova, Ray, and Pugliese 2011a, 2011b). Far higher rates of staying preferences exist in China (81%) and India (91%) (ibid.). Aspirations to migrate abroad permanently are even lower (see Figure 1). This situation begs the question, Why, given such great disparities in wealth, opportunity and security worldwide, do so many prefer to stay? After presenting a conceptual framework for the study of (im)mobility, I turn precisely to this question.

Framing (Im)mobility

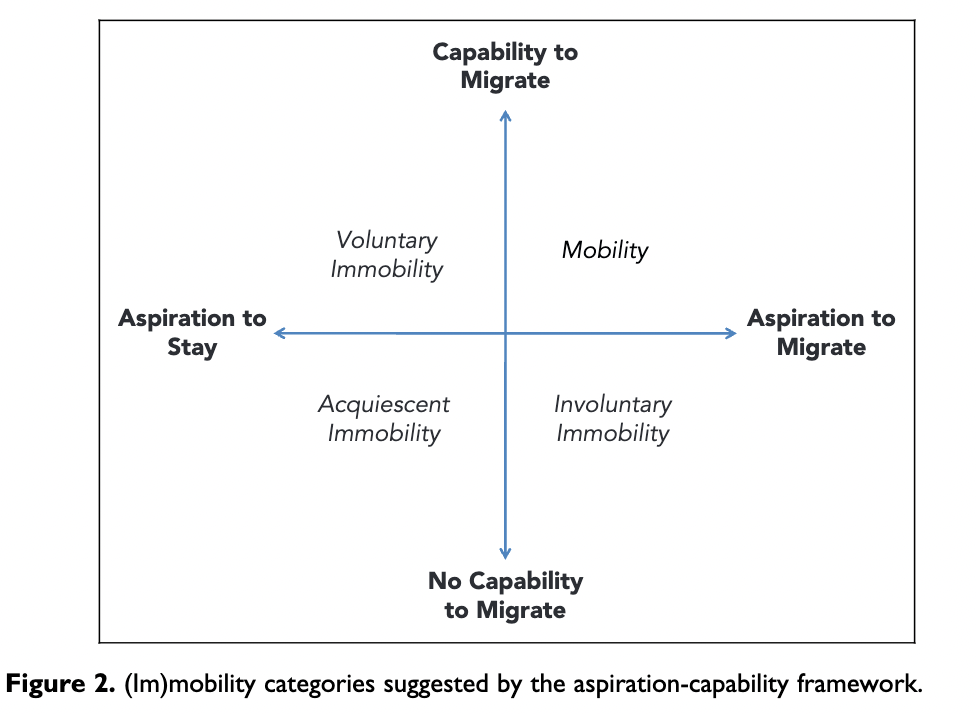

The aspiration-capability framework is a simple yet profound conceptual approach for studying mobility and immobility. Advancing theoretical frameworks specific to immobility and staying, as Stockdale and Haartsen (2018) suggest, risks further segregating immobility studies from migration studies. The aspiration-capability framework holds promise because it provides the conceptual tools to analyze processes that lead to both mobility and immobility outcomes. Carling (2002) proposed the first iteration of the framework after encountering widespread yet frustrated migration aspirations in Cape Verde. He decided to consider the aspiration and ability to migrate separately. Migration, Carling suggested, requires both, while immobility results from the lack of either one. The resultant “aspiration/ability model,” as he called it, proposed three mobility categories: mobility (i.e., having both the aspiration and ability to migrate), involuntary immobility (i.e., having the aspiration but not the ability to migrate), and voluntary immobility (i.e., having the ability but not the aspiration to migrate). Although aspiration and ability are not new concepts in migration studies (e.g., Woytinsky and Woytinsky 1953; Portes, McLeod, and Parker 1978), the novel contribution of Carling’s model is the ability to see, and therefore ask questions about, these distinct (im)mobility outcomes.

After studying changing mobility patterns in Morocco’s Todgha Valley, Hein De Haas (2003, 2010) replaced the term “ability” with the theoretically richer term “capability” to analyze how (im)mobility outcomes relate to development. De Haas drew on Amartya Sen’s capability approach, a normative framework that places the freedom to achieve well-being as development’s ultimate aim and suggests its evaluation in terms of people’s capabilities to do and be what they have reason to value (Sen 1999). De Haas (2014) argued that human mobility is also a freedom best conceptualized as a function of the aspiration and capability to migrate. To challenge the popular assumption that development would alleviate migration’s root causes in poor countries, he showed how on the contrary, development, which often increases income, access to education and media, infrastructure, and security, tends to enhance people’s aspirations and capabilities (i.e., their financial, social, and human capital) to migrate (De Haas 2007, 2010)2 (The reality that greater social and economic development tends to be associated with higherlevels of mobility, particularly in the short to medium term, was shown by many scholars inthe 1990s; see, for example, Martin and Taylor (1996) and Skeldon (1997) ).

Applying the concept of capability to Carling’s aspiration/ability model makes two important contributions. First, the concept of capability brings dynamism to the aspiration/ability model by more explicitly connecting (im)mobility outcomes to development processes, laying the groundwork to begin exploring why individuals transition across (im)mobility categories over time. However, it is important to recognize that the aspiration-capability framework need not be limited to “developing country” contexts. As Sen originally pointed out, expanding people’s capabilities to lead the lives they value is a relevant concern for every society (1999, 18). Examining how social transformations influence the aspiration and capability to migrate or stay is likewise valid across all socioeconomic contexts. Second, the concept of capability more explicitly links the ability to migrate (and the ability to stay) with the notion of “freedom” and, thus, human rights (see also Preibisch, Dodd, and Su 2016). In this regard, De Haas (2014) argues that people derive well-being from having the freedom to move or to stay, regardless of whether they act upon that freedom.

An important limitation of both Carling’s and De Haas’s work is their relative neglect of the category and determinants of voluntary immobility. Although Carling (2002) introduces the category of voluntary immobility, his main theoretical and empirical focus is the causes and experience of involuntary immobility. De Haas (2003) focuses on the development determinants of migration aspirations and capabilities, rather than the determinants of immobility. Many questions about voluntary immobility, thus, remain. What are the aspirations and capabilities of those who do not wish to migrate? Within the category of voluntary immobility, one can distinguish between those with and without the capability to migrate and question whether the immobility of those without the capability to migrate is voluntary in the same way as those who can migrate. I have found it useful to introduce a fourth (im)mobility category to the framework, acquiescent immobility (see Figure 2), to highlight those who do not wish to migrate and are unable to do so. The word acquiescent implies non-resistance to constraints, its Latin origins meaning “to remain at rest.” The category of acquiescent immobility challenges prevalent neoclassical and push-pull perspectives that assume the aspiration to migrate should be greatest among those who have the most to gain (often in economic terms) from migration (e.g., Todaro 1969; Sjaastad 1962). Since Ravenstein (1885) proposed the first “laws of migration,” it is a taken-for-granted assumption that people will move from low- to high-income places (De Haas 2011). Yet even though push factors are significant for many of the world’s poor and even though migration often brings substantial income gains, many people who migration theories assume should desire to migrate may not, in fact, wish to do so. Initial findings from a study of migration aspirations among young adults in Senegal, for example, show that over one fourth of those who did not have enough resources to meet their basic needs also did not desire to migrate (Schewel 2015) — a reality existing migration theories would struggle to explain.

It should be noted that capabilities and aspirations are not things that one simply has or does not have; they exist along a spectrum. Because one’s resources and desires change over time, one’s place along these spectrums changes too. These (im)mobility categories are, accordingly, best understood as ideal types instead of rigid categories with fixed, empirical demarcations. Accordingly, the aspiration-capability framework should be used as an orienting conceptual approach to the study of (im)mobility. It does not in itself explain how the various determinants of the aspiration and capability to migrate or stay relate to one another or vary across social groups, or why some contexts may have higher levels of immobility than others. Rather, it provides conceptual tools for investigating these questions. In an interdisciplinary field characterized by fragmentation (Massey et al. 1999), such a conceptual framework can lend coherence to the study of (im)mobility within migration studies (Carling and Schewel 2018).

Three potential critiques of using the aspiration-capability framework as a tool for studying (im)mobility should be addressed. First, one might argue that this framework fails to adequately account for the dynamics of mobility and immobility under conditions associated with forced migration. Indeed “forced mobility” is not presented here as a distinct (im)mobility category in relation to the capability to migrate. This is because, as Carling (2002) notes, there is no clear theoretical distinction between “forced” and “voluntary” migration, as almost all forms of migration entail choices and constraints (see also Van Hear 1998). A migration “aspiration” is defined simply as “a conviction that migration is preferable to non-migration; it can vary in degree and in the balance between choice and coercion” (Carling and Schewel 2018, 946). The aspiration-capability framework thus applies across the spectrum of “forced” to “voluntary” migration and, I would argue, the spectrum of “forced” to “voluntary” immobility. In other words, aspiration and capability are helpful concepts within both migration and refugee studies. Consider: even though many refugees fleeing violence and conflict may ideally aspire to stay in their home country, they nevertheless prefer to leave, taking all factors into account. In this context, the desire to leave would constitute a “migration aspiration.” However, only those with enough resources, or greater migration capabilities, can act upon this aspiration. This distinction between aspiration and capability helps clarify why the number of internally displaced persons (40 million in 2016) is nearly double the number of displaced peoples who cross international borders (UNHCR 2016). It also alerts us to the fact that the most vulnerable may not be able to move at all. As Lubkemann (2008) highlights, those who cannot leave war-torn settings, the “displaced in place” or “involuntarily immobile,” remain theoretically invisible in refugee studies.

Second, the aspiration-capability framework could be misunderstood as inherently individualistic, a critique often raised against Sen’s capability approach as well (Robeyns 2005). Although the framework is generally applied to analyze individuals’ (im)mobility outcomes, Carling (2002) describes the fundamentally social dynamics through which the aspiration and ability to migrate are shaped. De Haas (2003, 2014) explores how individual determinants of (im)mobility interact with broader processes of development in order to discern patterned shifts in the (im)mobility of populations over time. The aspiration-capability framework is therefore not individualistic at an ontological level3 (The aspiration-capability approach does not assume that social phenomena can in principle be explained in terms of individuals and their properties alone (see Robeyns [2005] for a related discussion on individualism and the capability approach).). Furthermore, the framework complements household approaches to migration studies (the primary counter-approach to atomistic methodologies) by helping disentangle the (im)mobility dynamics of various household members, thereby providing crucial insight into how mobility and immobility interact.

Relatedly, a third potential critique is that the aspiration-capability framework treats mobility and immobility as fundamentally separate outcomes with their own distinct processes. On the contrary, it actually helps clarify why mobility and immobility are so often intertwined. Numerous examples support the claim that the aspiration and capability to migrate (or to stay) often depends on others’ immobility (or mobility). New economic labor migration theory, for example, arose from the observation that mobility and immobility are often part of the same household livelihood strategy to diversify income and reduce risk; at the household level, an individual’s migration may be integral to the livelihood strategies of those “left-behind” (Stark 1984; Stark and Bloom 1985). De Haas (2003) found that in Morocco, migration was often a strategy of what Heinemeijer et al. (1977) called “partir pour rester,” or “leaving in order to stay” (as cited in De Haas 2003, 99). The migration and remittances of some enabled others to stay at home and continue agricultural lifestyles — what they perceive as the good life (see also Diatta and Mbow 1999). At the same time, “migrants too need people who stay behind and look after their children and their parents, or simply to preside over those social and cultural institutions that make their investments meaningful” (Gaibazzi 2010, 18). From a household perspective, then, the aspiration-capability framework helps clarify why mobility and immobility are often two sides of the same coin, mutually constitutive and reinforcing.

Explaining Immobility

The aspiration-capability framework suggests two explanations for why people stay in their places of residence (whether measured by local, regional, or national boundaries): (1) that a person lacks the capability to move or (2) that staying is a voluntary (or acquiescent) preference. Capability constraints may be political or legal (e.g., migration controls; Massey et al. 1999), economic (e.g., lack of financial capital to migrate; Van Hear 2014), social (e.g., lack of human or social capital; Kothari 2003), or even physical (e.g., border walls and detention centers; Turner 2007). However, constraints alone tell us little about the categories of voluntary and acquiescent immobility, the understanding of which entails asking why some individuals or households prefer to stay where they are.

Examining the preference to stay promises to enhance understandings of migration decision-making. As De Jong and Fawcett note, “Addressing the question of why people do not move is as significant as the analysis of why they do in understanding migration decision-making” (1981, 29–30). In this regard, prevalent rational-choice models frame migrant decision-making in terms of an individual cost/benefit analysis (Haug 2008), but when costs and benefits are framed in strictly economic terms (e.g., income-maximization), rational-choice models fail to predict real-world migration trends (Hammar and Tamas 1997; Malmberg 1997). People neither universally migrate to areas where the highest income can be obtained nor migrate when it would be economically beneficial to do so (Uhlenberg 1973; Hammar and Tamas 1997; Irwin et al. 2004). As I show below, the same phenomena that rational-choice frameworks struggle most to explain — behaviors related to family, religion, or gender (Hechter and Kanazawa 1997) — come to the fore in explanations of immobility. Interrogating immobility preferences is thus crucial to understanding migration decision-making: when the preference to stay overrides compelling economic reasons to go, non-economic values and economic “irrationality” cannot be overlooked.

This section briefly presents a number of existing explanations for the preference to stay found across the social sciences. I primarily consider research on migration decision-making from the fields of geography, economics, sociology, psychology, and anthropology and, within these fields, studies that address immobility directly. Related literature not systematically considered here includes research into the experience or consequences of immobility4 (For insightful special issues into the experiences and consequences of immobility, see Gender, Place, and Culture18, no. 3 (2011) for feminist and gendered perspectives on“waiting” and migrant (im)mobility;Population, Space and Place13 (2007) on the“Migration-Left-Behind nexus” in Asia; andIdentities18, no. 6 (2011) for anthropological takes on (im)mobility.), as well as more philosophical reflections on the relationship between mobility and “moorings” in social life (see Urry 2003; Adey 2006).

I consolidate explanations for immobility preferences into three categories: factors that “retain,” factors that “repel,” and factors described as “internal constraints” on decision-making. Retain factors refer to attractive conditions at home that bolster the preference to stay. Repel factors describe conditions elsewhere that diminish the aspiration to migrate. The third category of explanations addresses more nuanced influences on decision-making at the level of individual psychology that attempt to explain why some people may not meaningfully consider alternatives to staying.

It is important to clarify that I use the terms “retain” and “repel” heuristically, as counterparts to the concepts of “push” and “pull,” which, despite the latter’s shortcomings, remain intuitively resonant parts of the migration discourse (Van Hear, Bakewell, and Long 2018). Push-pull models are rightly criticized on multiple fronts: for neglecting migrant agency (De Haas 2011), for overlooking the influence of more intangible forces like social norms and expectations on migration decision-making (Schewel 2015), and for being espoused as a theory, when really they are descriptive factors without an explanatory system (Skeldon 1990). If, however, we set aside the impulse to take the push/pull framework as a theory, we are liberated to explore the range of potential factors that influence migration decision-making — factors that inevitably vary in their impact, intensity, and intersection across contexts and social groups (see also Lee 1966, 50). It is in this spirit that I use the concepts of “retain” and “repel” to highlight a range of potential influences on migration decision-making that go beyond its drivers.

Beginning with retain factors: in some cases, staying put can make economic sense, even if greater incomes may be had elsewhere. For example, economists and geographers introduce notions of “territorially restricted capital” and “location-specific advantages” that increase “place utility” over time (DaVanzo 1981; Straubhaar 1988; Fischer, Martin, and Straubhaar 1997). People develop knowledge, skills, and relationships specific to a particular place or firm, thereby acquiring insider advantages like opportunity, career, and leisure assets that would be lost by migrating. Accordingly, the longer someone lives in a place, the more economically embedded she or he tends to become, and the more she or he stands to lose by leaving (Fischer, Martin, and Straubhaar 1997)5 (To explain why so few people move, some economists also propose that people have a natural “home bias,” or an embedded preference for their home location (Faini and Venturini2001). This proposition suggests the marginal utility of consumption at home is always higher than elsewhere, biasing people toward a stay (or return) decision (Djajic ́ and Mil-bourne 1988; Vogler and Rotte 2000). Although the concept of a “home bias” is potentially valid, scrutinizing the notion that it is natural and exploring its underlying explanations can help explain why some people show a stronger home bias than others.).

The notion of “embeddedness” is important to understand why migration propensities vary across the life course. It has long been observed that older people are less mobile than younger people, less likely to aspire to migrate, and less likely to carry out their mobility plans (Bogue 1959; Goldscheider 1971; De Jong and Fawcett 1981; Esipova, Ray, and Pugliese 2011a, 2011b). As Fischer and Malmberg (2001) claim in their study of (im)mobility across the life course in Sweden, “settled people don’t move”; they find that the longer someone lives in a place, the stronger his or her ties to other people and projects, and the less likely he or she is to leave them. In fact, residence length is one of the most consistent positive predictors of what environmental psychologists and geographers refer to as “place-attachment,” the emotional bonds people develop to particular physical and social environments (Lewicka 2011).

Embeddedness has both social and economic dimensions. Social retain factors, such as family and community relations in origin areas, appear to be particularly important to explain the preference to stay. Researchers, for example, propose the “affinity hypothesis” to suggest that family and friends are a valued aspect of life that tends to dissuade migration (Ritchey 1976; De Jong and Fawcett 1981; Haug 2008), and studies often find that being married, having children, and having stronger social ties, when incorporated into migration decision-making, increase the likelihood of staying (Ritchey 1976; Mincer 1978; Lauby and Stark 1988; Fischer, Martin, and Straubhaar 1997; Mulder and Malmberg 2014). Greater community engagement can also reinforce the aspiration to stay. For example, Uhlenberg (1973) explained unexpectedly high rates of immobility in southern Appalachia in the United States from 1930 to 1960 by arguing that tightly knit community dynamics countered classical push factors like high rates of poverty and unemployment (see also Barcus and Brunn 2009). In a comparative study of migrant and non-migrant groups in Iran, Chemers, Ayman, and Werner (1978, 47) found that religious practice was a strong force that “drew villagers and returnees to the village.” In the United States, Myers (2000) introduces the concept of “location specific religious capital” to explain his finding that involvement in a religious community discouraged migration over time. Irwin et al. (2004) argue that certain configurations of local community-oriented institutions foster a greater likelihood of staying: the presence of churches, local gathering places, and local businesses are all associated with higher probabilities that individuals will remain where they are.

These retain factors help explain why people may come to see “home” as a better place to be than “elsewhere.” However, even when local conditions deteriorate, people may still choose to stay out of a sense of “loyalty” or to exercise “voice,” to use Hirschman’s terms (1970). Consider, for example, the rebel fighters in Syria who refused to flee (Hall 2016) or a young educated woman in Senegal with the opinion that “we must stay and develop our country” (Schewel 2015, 23)6 (The concept of “loyalty” has received less attention than the categories of exit or voice in relation to international migration (Dowding et al. 2000) and remains conceptually vague.Loyalty is loosely theorized as patriotism (Moses 2005) or social ties to one’s homeland(Hoffmann 2010). Practically, loyalty refers to staying in one’s origin area without voicing discontent, yet its manifestations can range from “enthusiastic support to passive acceptance or even submissive silence” (Hoffman 2010, 57; see also Van Hear 2014; Ahmed 1997).). This commitment to place, especially when staying goes against self-interest, presents another challenge to rational-choice paradigms in which the maximization of personal advantage is taken as the orienting principle of decision-making.

The second category of explanations are “repel factors,” or the negative perceptions about the migration process and imagined destinations that diminish the aspiration to migrate. When considering whether to migrate, migrants make decisions in relation to the people and projects where they are, as well as in relation to imagined worlds elsewhere (Sladkova 2007). Narratives about migration are often contradictory, and learning about the negative aspects of life in other places can dampen the allure of leaving (Sladkova 2007; Mata-Codesal 2015). The nature and functioning of “repel factors” have arguably received less attention than retain factors in theoretical explanations for immobility7 (One notable exception is Lee (1966), whose original model of migration decision-making included attract and repel factors at both origin and destination). Still, empirical studies of migration decision-making suggest that repel factors span social, economic, political, and cultural dimensions — ranging from the prospect of unemployment (Todaro 1969) to the perceived moral deprivation of Western countries (Gardner 1993) to the physical dangers and risks of the migration journey itself (Sladkova 2007).

Repel factors are often communicated through migrant networks (Mabogunje 1970). Research on migrant networks tends to focus on how networks facilitate migration, influence destination-selection, and perpetuate migration flows (Epstein and Gang 2006; Epstein 2008; Haug 2008), but there is also evidence for “negative feedback mechanisms” (Faist 2004; De Haas 2010). As Mabogunje (1970) stated in relation to rural-urban migration,

Migrants are never lost…to their village or origin but continue to send back information. If the information from a particular city dwells at length on the negative side of urban life, on the difficulties of getting jobs, of finding a place to live, and on the general hostility of people, the effect of this negative feedback will slow down further migration from the village. (12)

In recent decades, some governments and international organizations have attempted to amplify the weight of repel factors in potential migrants’ decision-making by employing information campaigns that broadcast the dangers and difficulties of the (particularly irregular) migration process (Pécoud 2010). However, their effectiveness remains debatable; personal networks are often more credible sources of information about conditions elsewhere (Pécoud 2010; Browne 2015).

Of course, not all people perceive and respond to repel factors in the same way. As Lee (1966) originally argued, “It is not so much the actual factors at origin and destination as the perception of these factors which results in migration,” and perceptions vary according to “personal sensitivities, intelligence, and awareness of conditions elsewhere” (51). One of the “personal sensitivities” that tends to dissuade migration is risk aversion. Early development economists proposed that what distinguished migrants from non-migrants was, respectively, a “love” or “aversion” to risk (Sahota 1968). Others countered that risk aversion was a global phenomenon and that migration should be understood as a way of lowering risks in the face of economic uncertainty (Stark and Levhari 1982; Katz and Stark 1986). More recent studies seem to confirm a positive relationship between risk aversion and staying behavior (Jaeger et al. 2010) yet show that risk attitudes fluctuate in relation to changing prospects at home and elsewhere (Czaika 2015).

Risk aversion fits within a category of explanations for the preference to stay that may be described as “internal constraints” on migration decision-making (Desbarats 1983, 352; Fawcett 1986). The idea here is that just as external capability constraints impede the ability to migrate, internal constraints impede the development of the aspiration to migrate. There are some for whom the very idea of “migration decision-making” is irrelevant; the possibility of migrating, the weighing of its potential benefits and costs, is never consciously considered. Hugo (1981), for example, in a detailed study of migration decision-making, suggests that for some in West Java, “no alternatives to a staying strategy have entered their calculations” (193; see also Hugo 1978). Similarly, Van Houtum and Van Der Velde (2004) explain unexpected levels of immobility in the European Union, despite open borders, with the concept of an “attitude of nationally habitualised indifference.” This “threshold of indifference” means that for many, their consciousness of livelihood possibilities stops at the border (ibid., 102).

The inability to think “beyond the border” can, from one perspective, be explained in terms of cognitive constraints on decision-making. For example, Simon (1982) introduced the concept of “bounded rationality” to explain why people do not behave according to the predictions of neoclassical theory. Because of limitations in knowledge and computational capacity, people tend to choose alternatives that are “good enough” rather than the best course of action among all those available (ibid.). Other migration scholars propose constraints beyond the bounds of rationality: the force of social norms or the internalization of external constraints may lead some to circumscribe their imagined futures to more feasible, local options (Desbarats 1983; McHugh 1984).

From another perspective, more recent research suggests that “low” aspirations may limit the horizons of what people imagine for their futures. For example, Czaika and Vothknecht (2014) argue that migration is both a cause and a consequence of higher aspirations; even when accounting for factors such as age, education, and socio-economic background, migrants show higher aspirations than their non-migrant counterparts. Similarly, Boneva et al. (1998) claim that migrants show higher levels of “achievement motivation” than non-migrants. This perspective resonates with a strand of research in development thinking that frames “aspirations failure” as an obstacle to development and gives attention to raising aspirations among poor populations (World Bank 2015; Dalton, Ghosal, and Mani 2016). De Haas (2007, 2014) arguably adopts a similar perspective when he proposes that development processes tend to increase aspirations and thereby the desire to migrate.

But what kinds of aspirations are we talking about? The dataset used by Czaika and Vothknecht (2014) clearly measured economic aspirations, asking respondents to imagine a six-step ladder with the poorest people on the first step and the richest on the sixth and to state their current and expected future position. Those who expected higher incomes in the future were described as those with higher aspirations, or a greater “capacity to aspire” (c.f. Appadurai 2004). But surely other “high” aspirations exist that do not entail higher incomes or migration, such as the desire to exercise “voice” at home (ibid.; see also Schewel 2015). It is, thus, important to disentangle high aspirations from those we might attribute to the ideal homo economicus, in this case a bold and geographically mobile income-maximizing agent. Studying the broader life aspirations of individuals and families, especially of those who do not migrate, is one important way of doing so.

Finally, like migration, immobility is deeply gendered (see Pedraza 1991; Mata-Codesal 2015). In some contexts, gendered norms may be characterized as internal constraints — for example, the expectation that women fulfill social roles at home, such as caring for children or the elderly (Haberkorn 1981; Hugo 1981; De Jong 2000). The notion of gendered norms as “internal constraints” is present within the broader gender studies literature, where it is well established that people are socialized to view gendered distinctions “as natural, inevitable, and immutable” (Mahler and Pessar 2001, 442). Yet explaining gendered differences in the motivation to stay in terms of internal constraints easily slips into a devaluing of non-economic motivations. As Lutz has argued, a gendered perspective on migration decision-making is also an opportunity to “exceed economic reductionism” and to “show a multiplicity of motives other than purely economic ones for pursuing or refraining from migration projects” (2010, 1659).

To summarize, examining the preference to stay helps illuminate the positive value of immobility. Economic investments, opportunities, and advantages, as well as a dynamic social life, community engagement, and place commitment, can be “location-specific”; that is, they would be lost by migrating. These retain factors tend to strengthen over the life cycle. When the value of immobility is assessed in relation to imagined alternatives, negative perceptions about the migration process and life elsewhere further strengthen immobility preferences. However, for some, the preference to stay may reflect a lack of imagined alternatives. Not everyone meaningfully engages in “migration decision-making” per se. The reasons why remain puzzling: is it a reflection of cognitive constraints, the internalization of social norms, or “low” aspirations? The explanations we, as scholars, offer need to be careful not to devalue non-economic motivations that may vary across gender, age, or class. Further research on the aspirations and capabilities of those who stay, how they understand their present and consider their future, promises to enrich and refine this initial review of explanations. The following section suggests ways that such research could proceed.

Studying Immobility

Advancing a research agenda on immobility requires definitional clarity. I propose defining immobility as continuity in an individual’s place of residence over a period of time. Immobility is never absolute because all people move to some degree or another in their everyday lives; rather, it is always relative to spatial and temporal frames. The “spatial frame” designates the boundaries within which an individual may be deemed “immobile.” For example, someone who has moved from a rural village to a nearby city may be immobile relative to international movement. However, this same person may be considered highly mobile relative to those who stay in the village. The “temporal frame” designates the period of time within which the researcher wishes to assess (im)mobility outcomes. Immobility can refer to lifetime staying behavior, periods of spatial continuity across the life course, or even immobility across generations. Setting a time frame is particularly important. Examining immobility over a shorter time frame is easier to assess and allows immobility to be a relevant research subject for migrants and non-migrants alike. As with migration, then, what counts as “immobility” depends on the research question and context.

Once defined, methodological strategies to study immobility may be as diverse as those used for migration. However, one approach to migration research which resonates with the logic of the aspiration-capability framework holds particular promise for the further empirical study of (im)mobility. Referred to as “two-step approaches” to migration (Carling and Schewel 2018), these studies span the quantitative and qualitative domains yet share the analytical distinction between (1) the evaluation of migration as a potential course of action and (2) the realization of actual mobility or immobility at a given moment. The first step has been analyzed in terms of migration aspirations, desires, intentions, plans, needs, and “potential migration”; and the second in terms of migration ability, capabilities, and “actual migration” (e.g., McHugh 1984; Lu 1999; De Groot et al. 2011; Creighton 2013; Van Heelsum 2016; Mata-Codesal 2018; see Carling and Schewel 2018).

Docquier, Peri, and Ruyssen (2014) provide an illustrative example of a two-step approach to migration. Using Gallup World Poll data on migration aspirations and cross-country bilateral data, they explore the aggregate determinants of “potential” and “actual” international migration. The authors find that average income and migrant networks are critical determinants of the aspiration to migrate, while education levels and economic growth in the destination country are key factors influencing the realization of emigration desires. Although the characteristics of non-migrants can to some degree be inferred from their findings, further research should directly examine the determinants of “potential” and “actual” immobility to reveal different predictors of involuntary, voluntary, or acquiescent immobility.

Opportunities to assess “potential” immobility, or the desire to stay, increase with the growing number of surveys that ask about international migration aspirations8 (See Carling and Schewel (2018) for a review of recent migration aspiration surveys.). However, because the choice to move within one’s country is often a more viable alternative than international migration (Malmberg 1997), future surveys should examine (im)mobility aspirations relative to both internal and international boundaries. Doing so would allow researchers to explore the degree to which staying or internal mobility strategies act as imagined alternatives to international migration. The Young Lives project provides one illustrative methodology: it is a longitudinal, cross-country survey that asks whether respondents would like to move “to another place,” and if so, where they would be most likely to move, categorizing responses according to their administrative boundaries (a rural area, a small town in the district, a regional city, a capital city, abroad, etc.). Subsequent rounds reassess aspirations and actual moving behavior (Boyden et al. 2016). This approach enables researchers to explore the spatial horizons of imagined futures, changes in (im)mobility aspirations over time, and links between aspirations and actual behavior (see Schewel and Fransen 2018).

The second step, “actual” immobility, is easier to access over shorter time frames. For example, Lu (1999) uses American Housing Survey data to examine the links between residential mobility intentions and actual moving behavior over a four-year period and the sociodemographic factors that predict (im)mobility outcomes within this time frame. Lifetime stayers are admittedly harder to capture from a quantitative perspective. Long-running panel datasets, such as Panel Study of Income Dynamics or the UK Household Longitudinal Study, provide the opportunity to trace (im)mobility outcomes over time, but researchers should be attentive to potential attrition related to moving and to potential movement that occurs between moments of data collection (Mulder 2018). In European Labour Force Survey or American Community Survey data, for example, a “non-mover” is someone whose place of residence is the same across three data points: at birth, one or five years ago, and at the time of the survey. Measuring immobility in this way masks any movement occurring between the three data points; nevertheless, it does give some indication of stability in an individual’s center of gravity over time. Population register data can provide more accurate records of long-term immobility, but sufficiently detailed registers are available for relatively few countries (e.g., Nordic countries or the Netherlands) and still rely upon inhabitants recording and updating their data (ibid.). Another alternative is life-history surveys. Although subject to retrospective biases, life-history surveys allow researchers to examine a wider range of (im)mobility patterns across the life course and are more easily tailored to researchers’ interests (see DaVanzo 1981).

Complementary to large datasets, life history methods, pioneered by Thomas and Znaniecki (1918) in their seminal The Polish Peasant in Europe and America: Monograph of an Immigrant Group, remain relatively rare in migration studies but are particularly well-suited to explore immobility as a process, with determinants and consequences that shift across the life course. Micro-level case studies and more qualitative methods can provide nuanced insight into the contexts that shape each step of a two-step approach: the sociocultural contexts in which (im)mobility aspirations emerge; the opportunities, constraints, and social relations that shape the nature and realization of these aspirations; the ways in which aspirations and capabilities shift at different stages of the life course; and how people experience and make sense of their immobility at a given time (e.g., Jónsson 2008; Bordorano 2009; Vigh 2009; Hjälm 2014; Gaibazzi 2010; Mata Codesal 2015). Ethnographic methods are perhaps best suited to further insight into some of the most puzzling questions about immobility, such as why some people may not engage with the first step of a two-step approach, “migration decision-making,” at all.

Many questions for further research remain, particularly regarding the aspiration and capability to stay. Regarding immobility aspirations, for example, is it possible to speak about a “culture of staying” (Stockdale and Haartsen 2018) in the same way that we speak of a “culture of migration” (Kandel and Massey 2002)? Is immobility also a learned social behavior; do people learn to stay and to desire to stay (cf. Ali 2007, 39)? Regarding the “capability to stay,” one limitation to the aspiration-capability framework described here is that it presents (im)mobility categories in relation to the capability to migrate. To fully exploit the potential of the concept “capability” as Sen (1999) originally used it, an aspiration-capability approach should also interrogate the conditions that enable the realization of one’s aspirations at home. After all, Sen defines development as the process of expanding the capabilities and freedoms people have to realize the lives they value — whether at home or elsewhere. In migration and development research, then, scholars should look not only at the relationship between development processes and the capability to migrate (cf. De Haas 2010) but also at how the social transformations associated with development enhance or reduce the capability to stay.

Conclusion

Examining the causes and consequences of immobility is an opportunity to understand migration processes in a new way. Because of a mobility bias in migration research, migration theories share a focus on migration’s “drivers” — the forces that lead to the initiation and perpetuation of migration flows — often overlooking the countervailing structural and personal forces that restrict or resist it. As a result, existing migration theories struggle to explain widespread immobility preferences and behavior. To better understand contemporary mobility dynamics, scholars should also turn their attention to the determinants of immobility.

To advance a research agenda on immobility, this article has proposed the aspiration-capability framework as a simple yet profound conceptual approach. The different (im)mobility categories the framework suggests each shed light on important social forces relevant to migration studies. Examining involuntary immobility, for example, illuminates the complex capability constraints potential migrants face. Widespread involuntary immobility challenges the notion that mobility is the motif of modernity (Carling 2002), revealing instead that inequalities in access to and control over mobility are key features of globalization. However, it is important to recognize that immobility is not always a result of constraints and that modernization is not always equivalent with the aspiration to be mobile. The desire to stay is far more common than disparities in wealth or population would predict. Examining the determinants of voluntary and acquiescent immobility, then, moves migration decision-making models away from a rational economic calculus to include the non-economic values and “irrationality” that lead many to prefer to stay where they are. Finally, these immobility categories highlight that, far from the neutral backdrop or passive alternative to migration, immobility is dynamic and differentiated. Immobility may be the purview of the privileged who have the capability to stay and resist or flourish in the face of social change, or it may be a prison for those who lack the capability to leave. Immobility, and control over immobility, reflects and reinforces power in what we have (perhaps erroneously) come to define as the “age of migration” (cf. Massey 1994, 150; Castles, De Haas, and Miller 2014).

Acknowledgments

With gratitude to Jørgen Carling, Hein de Haas, Sonja Fransen, Katharina Natter, Simona Vezzoli and several anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on earlier versions of this article, and to Haleh Arbab, Geoffrey Cameron, Katyana Melic, Stephen Murphy, and Ben Schewel whose thoughtful discussions helped shape my approach to migration studies.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research is part of the MADE (Migration as Development) Consolidator Grant project and has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Community’s Horizon 2020 Programme (H2020/2015-2020)/ERC Grant Agreement 648496.

References

- Adey, P. 2006. “If Mobility Is Everything Then It Is Nothing: Towards a Relational Politics of (Im)Mobilities.” Mobilities l(l):75-94.

- Ahmed, I. 1997. “Exit, Voice, and Citizenship.” In International Migration, Immobility and Development: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by T. Hammar, G. Brochmann, K. Tamas, and T. Faist, 159-85. Oxford: Berg.

- Ali, 8. 2007. “‘Go West Young Man’: The Culture of Migration among Muslims in Hyderabad, India.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33(l):37-58.

- Appadurai, A. 2004. “The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition.” In Culture and Public Action, edited by V. Rao and M. Walton. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Arango, J. 2000. “Explaining Migration: A Critical View.” International Social Science Journal 52(165) :283-96.

- Bakewell, O. 2008. “‘Keeping Them in Their Place’: The Ambivalent Relationship between Development and Migration in Africa.” Third World Quarterly 29(7): 1341-58.

- В arcus, H. R, and S. D. Brunn. 2009. “Towards a Typology of Mobility and Place Attachment in Rural America.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 15:26-48.

- Bauman, Z. 1998. Globalization: The Human Consequences. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bell, M., and E. Charles-Edwards. 2013. Cross-National Comparisons of Internal Migration: An Update of Global Patterns and Trends. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- Bogue, D. 1959. “Internal Migration.” In The Study of Population: An Inventory and Appraisal, edited by P. Hauser and O. D. Duncan, 486-509. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Boneva, В., I. H. Frieze, A. Ferligoj, E. Jarosovä, D. Pauknerovä, and A. Orgocka. 1998. “Achievement, Power, and Affiliation Motives as Clues to (E)Migration Desires: A Four- Countries Comparison.” European Psychologist 3(4):247-54.

- Bordonaro, L. 2009. “Sai Fora: Youth, Disconnectedness and Aspiration to Mobility in the Bijago Islands (Guinea-Bissau).” Etnogrdfica 13(l):125-44.

- Boyden, J., T. Woldehanna, S. Galab, A. Sanchez, M. Penny, and L. T. Due. 2016. “Young Lives: An International Study of Childhood Poverty: Round 4, 2013-2014.” UK Data Service. SN: 7931. http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7931-l.

- Browne, E. 2015. “Impact of Communication Campaigns to Deter Irregular Migration.” In GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1248. Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

- Carling, J. 2002. “Migration in the Age of Involuntary Immobility: Theoretical Reflections and Cape Verdean Experiences.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28(l):5-42.

- --- , and K. Schewel. 2018. “Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44(6):945-63.

- Castles, S., H. De Haas, and M. J. Miller. 2014. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. 5th ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chemers, M. M., R. Ayman, and C. Werner. 1978. “Expectancy Theory Analysis of Migration.” Population & Environment l(l):42-56.

- Cohen, J. H. 2002. “Migration and ‘Stay at Homes’ in Rural Oaxaca, Mexico: Local Expression of Global Outcomes.” Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 31(2):231-59.

- Collyer, M., F. Düvell, and H. De Haas. 2012. “Critical Approaches to Transit Migration.” Population, Space and Place 18(4):407-14.

- Coulter, R., M. van Ham, and A. M. Findlay. 2016. “Re-Thinking Residential Mobility: Linking Lives through Time and Space.” Progress in Human Geography 40(3):352-74. doi:10.1177/0309132515575417.

- Creighton, M. J. 2013. “The Role of Aspirations in Domestic and International Migration.” Social Science Journal 50(l):79-88.

- Cresswell, T. 2006. On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. New York: Routledge.

- Czaika, M. 2015. “Migration and Economic Prospects.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41(l):58-82.

- --- , and M. Vothknecht. 2014. “Migration and Aspirations - Are Migrants Trapped on a Hedonic Treadmill?” IZA Journal of Migration 3(1):1-21.

- Dalton, P., S. Ghosal, and A. Mani. 2016. “Poverty and Aspirations Failure.” Economic Journal 126(590): 165-88.

- DaVanzo, J. S. 1981. “Microeconomic Approaches to Studying Migration Decisions.” In Migration Decision Making: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries, edited by G. De Jong and R. W. Gardner. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- De Groot, С., C. Mulder, M. Das, and D. Manting. 2011. “Life Events and the Gap between Intention to Move and Actual Mobility.” Environment and Planning A 43(1): 48-66.

- De Haas, H. 2003. Migration and Development in Southern Morocco: The Disparate Socio- Economic Impacts of out-Migration on the Todgha Oasis Valley. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Radboud University.

- --- . 2007. “Turning the Tide? Why Development Will Not Stop Migration.” Development and Change 38(5):819-41.

- --- . 2010. “Migration and Development: A Theoretical Perspective.” International Migration Review 44(l):227-64. doi:10.1111/j.l747-7379.2009.00804.x.

- --- . 2011. “The Determinants of International Migration: Conceptualizing Policy, Origin and Destination Effects.” International Migration Institute Working Paper Series (Working Paper 32): 1-35.

- --- . 2014. “Migration Theory: Quo Vadis?” International Migration Institute Working Paper Series (Working Paper 100): 1-39.

- De Jong, G. 2000. “Expectations, Gender, and Norms in Migration Decision-Making.” Population Studies 54(3):307-19.

- --- , and J. Fawcett. 1981. “Motivations for Migration: An Assessment and a Value- Expectancy Research Model.” In Migration Decision Making: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries, edited by G. De Jong and R. Gardner, 13-58. New York: Pergamon Press.

- --- , and R. W. Gardner. 1981. Migration Decision Making: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries. New York: Pergamon Press.

- Desbarats, J. 1983. “Spatial Choice and Constraints on Behavior.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 73(3):340-57.

- Diatta, M. A., and N. Mbow. 1999. “Releasing the Development Potential of Return Migration: The Case of Senegal.” International Migration 37(l):243-66.

- Djajic, S., and R Milboume. 1988. “A General Equilibrium Model of Guest-Worker Migration: The Source-Country Perspective.” Journal of International Economics 25(3):335-51.

- Docquier, F., G. Peri, and I. Ruyssen. 2014. “The Cross-Country Determinants of Potential and Actual Migration.” International Migration Review 48(Fall):S37-S99.

- Dowding, К., P. John, T. Mergoupis, and M. Vugt. 2000. “Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Analytic and Empirical Developments.” European Journal of Political Research 37(4):469-95.

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What Is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103(4):962-1023.

- Epstein, G. S. 2008. “Herd and Network Effects in Migration Decision-Making.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34(4):567-83.

- --- , and I. N. Gang. 2006. “The Influence of Others on Migration Plans.” Review of Development Economics 10(4):652-65.

- Esipova, N., J. Ray, and A. Pugliese. 2011a. Gallup World Poll: The Many Faces of Global Migration: Based on Research in More Than 150 Countries. Geneva: IOM (International Organization for Migration).

- --- , J. Ray, and A. Pugliese. 2011b. The World’s Potential Migrants: Who They Are, Where They Want to Go, and Why It Matters. The Gallup Organization, http://www.imi. =ox.ac.uk/pdfs/the-worlds-potential-migrants.

- Faini, R., and A. Venturini. 2001. “Home Bias and Migration: Why Is Migration Playing a Marginal Role in the Globalization Process?” CHILD Working Paper 27, Centre for Household, Income, Labour, and Domestic Economics. http://www.de.unito.it/CHILD.

- Faist, T. 2004. “Towards a Political Sociology of Transnationalization: The State of the Art in Migration Research.” European Journal of Sociology 45(3):331-66.

- --- . 2013. “The Mobility Turn: A New Paradigm for the Social Sciences?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36(11): 1637-46.

- Fawcett, J. T. 1986. “Migration Psychology: New Behavioral Models.” Population and Environment 8(l-2):5-14.

- Fischer, P., and G. Malmberg. 2001. “Settled People Don’t Move: On Life Course and (Im-) Mobility in Sweden.” International Journal of Population Geography 7(5):357-71. doi: 10.1002/ijpg.230.

- --- , R. Martin, and T. Straubhaar. 1997. “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” In International Migration, Immobility and Development: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by T. Hammar, G. Brochmann, K. Tamas, and T. Faist. Oxford: Berg.

- Gaibazzi, P. 2010. “Migration, Soninke Young Men and the Dynamics of Staying Behind.” PhD Thesis, University of Milano-Bicocca.

- Gardner, K. 1993. “Sylheti Images of Home and Away.” Man 28(1):1-15.

- Glick Schiller, N., and N. B. Salazar. 2013. “Regimes of Mobility across the Globe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39(2): 183-200.

- Goldscheider, C. 1971. Population, Modernization, and Social Structure. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Gray, B. 2011. “Becoming Non-Migrant: Lives Worth Waiting For.” Gender, Place & Culture 18(3):417-32. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2011.566403.

- Haberkom, G. 1981. “The Migration Decision-Making Process: Some Social-Psychological Considerations.” In Migration Decision Making: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries, edited by G. De Jong and R. Gardner, 252-78. New York: Pergamon Press.

- Hägerstrand, T. 1957. “Migration and Area.” In Migration in Sweden: A Symposium, edited by D. Hannerberg, T. Hägerstrand, and B. Odeving, 27-158. Lund, Sweden: C. W. K. Gleerup Publishers.

- Halfacree, K., and M. J. Rivera. 2012. “Moving to the Countryside... and Staying: Lives Beyond Representations.” Sociologia Ruralis 52(1):92-114.

- Hall, R. 2016. “Surrounded, Hungry and Afraid, Many in Aleppo, Syria Still Refuse to Leave.” GlobalPost, July 28.

- Hammar, T., G. Brochmann, K. Tamas, and T. Faist. 1997. International Migration, Immobility and Development: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. New York: Berg.

- --- , and K. Tamas. 1997. “Why Do People Go or Stay?” In International Migration, Immobility, and Development: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by T. Hammar, G. Brochmann, K. Tamas, and T. Faist. Oxford: Berg.

- Haug, S. 2008. “Migration Networks and Migration Decision-Making.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34(4):585-605. doi:10.1080/13691830801961605.

- Hechter, M., and S. Kanazawa. 1997. “Sociological Rational Choice Theory.” Annual Review of Sociology 23:191-214.

- Hirschman, A. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organization, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hjälm, A. 2014. “The ‘Stayers’: Dynamics of Lifelong Sedentary Behaviour in an Urban Context.” Population, Space and Place 20:569-80. doi: 10.1002/psp. 1796.

- Hoffmann, B. 2010. “Bringing Hirschman Back In: ‘Exit,’ ‘Voice,’ and ‘Loyalty’ in the Politics of Transnational Migration.” The Latin Americanist 54(2):57-73. doi:10.1111/j. 1557-203X.2010.01067.X.

- Hugo, G. 1978. Population Mobility in West Java. Yogya-karta: Gad)ah Mada University Press.

- --- . 1981. “Village-Community Ties, Village Norms, and Ethnic and Social Networks: A Review of Evidence from the Third World.” In Migration Decision Making: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries, edited by G. De Jong and R. Gardner, 186-224. New York: Pergamon Press.

- Hyndman, J., and W. Giles. 2011. “Waiting for What? The Feminization of Asylum in Protracted Situations.” Gender, Place & Culture 18(3):361-79.

- IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2015. Global Migration Trends Factsheet 2015. Geneva: IOM, Global Migration Data Analysis Centre.

- Irwin, M., T. Blanchard, C. Tolbert, A. Nucci, and T. Lyson. 2004. “Why People Stay: The Impact of Community Context on Nonmigration in the USA.” Population (English ed.) 59(5):567-91.

- Jaeger, D. A., T. Böhmen, A. Falk, D. Huffinan, U. Sunde, and H. Bonin. 2010. “Direct Evidence on Risk Attitudes and Migration.” Review of Economics and Statistics 92(3): 684—89.

- Jonsson, G. 2008. “Migration Aspirations and Immobility in a Malian Soninke Village.” International Migration Institute Working Paper Series (Working Paper 10): 1-45.

- --- . 2011. “Non-Migrant, Sedentary, Immobile or ‘Left Behind’? Reflections on the Absence of Migration.” International Migration Institute Working Paper Series (Working Paper 39): 1-17.

- Kandel, W., and D. S. Massey. 2002. “The Culture of Mexican Migration: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis.” Social Forces 80(3):981-1004.

- Katz, E., and O. Stark. 1986. “Labor Migration and Risk Aversion in Less Developed Countries.” Journal of Labor Economics 4(1):134—49.

- Kothari, U. 2003. “Staying Put and Staying Poor?” Journal of International Development 15(5):645-57. doi:10.1002/jid,1022.

- Lauby, J., and O. Stark. 1988. “Individual Migration as a Family Strategy: Young Women in the Philippines.” Population Studies 42(3):473-86.

- Lee, E. S. 1966. “A Theory of Migration.” Demography 3(l):47-57.

- Lewicka, M. 2011. “Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31(3):207-30.

- Lu, M. 1999. “Do People Move When They Say They Will? Inconsistencies in Individual Migration Behavior.” Population and Environment 20(5):467-88.

- Lubkemann, S. C. 2008. “Involuntary Immobility: On a Theoretical Invisibility in Forced Migration Studies.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21(4):454-75.

- Lutz, H. 2010. “Gender in the Migratory Process.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36(10): 1647-63. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2010.489373.

- Mabogunje, A. 1970. “Systems Approach to a Theory of Rural-Urban Migration.” Geographical Analysis 2:1-18.

- Mahler, S. J., and P. R. Pessar. 2001. “Gendered Geographies of Power: Analyzing Gender across Transnational Spaces.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 7(4): 441-59.

- Malkki, L. 1992. “National Geographic: The Rooting of Peoples and the Territorialization of National Identity among Scholars and Refugees.” Cultural Anthropology 7(1):24—44.

- Malmberg, G. 1997. “Time and Space in International Migration.” In International Migration, Immobility and Development, edited by T. Hammar, G. Brochmann, К Tamas, and T. Faist, 21-48. Oxford: Berg.

- Martin, P. L., and J. E. Taylor. 1996. “The Anatomy of a Migration Hump.” In Development Strategy, Employment, and Migration: Insights from Models., edited by J. E. Taylor, 43-62. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Massey, D. 1994. “A Global Sense of Place.” In Space, Place and Gender, 146-55. Minneapolis!, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Massey, D. 8., J. Arango, G. Hugo, A. Kouaouci, A. Pellegrino, and J. E. Taylor 1993. “Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal.” Population and Development Review 19(3):431-66.

- --- ,---- ,--------- ,---------- ,---------- , and----- . 1999. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Mata-Codesal, D. 2015. “Ways of Staying Put in Ecuador: Social and Embodied Experiences of Mobility-Immobility Interactions.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41(14): 2274-90.

- --- . 2018. “Is It Simpler to Leave or to Stay Put? Desired Immobility in a Mexican 'Village.” Population, Space and Place, https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2127.

- McHugh, K. 1984. “Explaining Migration Intentions and Destination Selection.” The Professional Geographer 36(3):315-25. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.1984.00315.x.

- Mincer, J. 1978. “Family Migration Decisions.” Journal of Political Economy 86:749-78.

- Moses, J. W. 2005. “Exit, Vote and Sovereignty: Migration, States and Globalization.” Review of International Political Economy 12(l):53-77.

- Mulder, С. H. 2018. “Putting Family Centre Stage: Ties to Nonresident Family, Internal Migration, and Immobility.” Demographic Research 39:1151-180. doi: 10.4054/ DemRes.2018.39.43.

- --- , and G. Malmberg. 2014. “Local Ties and Family Migration.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 46(9):2195-211. doi:10.1068/al30160p.

- Myers, S. M. 2000. “The Impact of Religious Involvement on Migration.” Social Forces 79(2):755-83.

- Pecoud, A. 2010. “Informing Migrants to Manage Migration? An Analysis of IOM’s Information Campaigns.” In The Politics of International Migration Management, 184—201. Amsterdam: Springer.

- Pedraza, S. 1991. “Women and Migration: The Social Consequences of Gender.” Annual Review of Sociology 17:303-25.

- Portes, A., S. A. McLeod, and R. N. Parker. 1978. “Immigrant Aspirations.” Sociology of Education 51(4):241-60. doi: 10.2307/2112363.

- Preece, J. 2018. “Immobility and Insecure Labour Markets: An Active Response to Precarious Employment.” Urban Studies 55(8):1783-99. doi: 10.1177/0042098017736258.

- Preibisch, K., W. Dodd, and Y. Su. 2016. “Pursuing the Capabilities Approach within the Migration-Development Nexus.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42(13): 2111-27.

- Ravenstein, E. Georg. 1885. “The Laws of Migration.” Journal of the Statistical Society of London 48(2): 167-235.

- Ritchey, P. N. 1976. “Explanations of Migration.” Annual Review of Sociology 2: 363-404.

- Robeyns, I. 2005. “The Capability Approach: A Theoretical Survey.” Journal of Human Development 6(1):93-117.

- Sahota, G. S. 1968. “An Economic Analysis of Internal Migration in Brazil.” Journal of Political Economy 76(2):218-45.

- Schewel, K. 2015. “Understanding the Aspiration to Stay: A Case Study of Young Adults in Senegal.” International Migration Institute Working Paper Series (Working Paper 107): 1-37.

- --- , and Fransen, S. 2018. “Formal Education and Migration Aspirations in Ethiopia.” Population and Development Review 44(3):555-87. doi: 10.1111/padr. 12159.

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shamir, R. 2005. “Without Borders? Notes on Globalization as a Mobility Regime.” Sociological Theory 23(2): 197-217.

- Sheller, M., and J. Urry. 2006. “The New Mobilities Paradigm.” Environment and Planning A 38(2):207-26.

- Simon, H. A. 1982. Models of Bounded Rationality: Empirically Grounded Economic Reason. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Sjaastad, L. 1962. “The Costs and Returns of Human Migration.” Journal of Political Economy 70(5):80-93.

- Skeldon, R. 1990. Population Mobility in Developing Countries: A Reinterpretation. London: Belhaven Press.

- -------- . 1997. Migration and Development: A Global Perspective. Harlow, UK: Longman.

- Sladkova, J. 2007. “Expectations and Motivations of Hondurans Migrating to the United States.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 17:187-202. doi: 10. 1002/casp.

- Stark, O. 1984. “Migration Decision-Making: A Review Article.” Journal of Development Economics 14:251-59.