Brand activism and millennials: an empirical investigation into the perception of millennials towards brand activism

Published: Dec. 2, 2019

Latest article update: Dec. 12, 2022

Abstract

T he reckless pursuit of social, environmental, political and cultural issues and brands may alienate the very customer base, whom they try to impress, especially the millennials. Hence, this study intends to study the perceptions of millennials towards brand activism, so that the findings from the study can help the brand managers to steer their brands into the troubled waters of brand activism. The methodology followed is HTAB (Hypothesize, Test, Action, Business), a popular analysis framework given by Ken Black in his book titled “Business Statistics: Contemporary Decision Making (6th ed.)” A sample comprising of 286 respondents was collected. The final data had 286 observations and 45 features across seven categories. It was found that millennials prefer to buy a brand if it supports a cause or purpose and they stop buying if brand behaves unethically. It was also observed that there is no gender difference amongst the millennials towards their perceptions concerning brand activism. Moreover, millennials across different income categories have similar perceptions of brand activism. It was also substantiated that the emotional tie of the millennials with the brand existing for a cause goes beyond price shifts and brands taking a political stance, cherry-picking of issues and being disruptive prompts and creates profound backlash for the brands

Keywords

Brand management, buycotting, brand activism, boycotting, millennials, brand equity

INTRODUCTION

Brand activism has been attracting the attention of marketers, brand managers and academicians throughout the world in general and in India in particular. The brand activism bandwagon has attracted not only the biggest brands of the world, but also the smaller brands. Brand activism takes place when a company or brand support promote the social, economic, environmental, cultural and social issue and align it with its core values and vision of the company. The brand activism may take the form of making an open statement in public domain, lobbying for the cause, donating money to the particular cause and making a cause-related statement through their marketing and advertising communication. This act of activism not only gets the attention of their target customer base, but also creates the buzz around the brand and publicity. Apart from creating the buzz around the brand, activism helps the brands and companies to have a favorable impact on their profits, enhances customer loyalty and association with them who share the common values and principles. Moreover, when the brands and companies can connect with their target customer base on emotional issues that tie goes beyond the product quality or even for that matter price.

Whereas, on the negative side of the brand activism, if the activism of the brands is not in complete sync and match with their core values, ethics and vision, it may be seen as mere advertising and marketing gimmick and may alienate core customer base. Even worse, sometimes, brand activism and its campaigns may invite backlash and boycotting from the customer base having different social, cultural, political and environmental beliefs. Hence, it can be said that brand activism is partly science and partly arts. If it is implemented properly, it may align the customers with company values and if it is done improperly, it may alienate its loyal customers.

Therefore, brands cannot afford to be a neutral spectator when the new generation of customers, i.e., millennials prefer to get identified with those brands, which are socially responsive, having high ethical standards and morally superior. They are also perceived to be more civic-minded, marketing savvy and know the true intentions of the brand and more skeptical about the brand claim. This new mindset of the millennials will force the brand managers and marketers to abandon their mundane and traditional marketing approaches and adopt a new set of strategies to relate their brand ethos with the personal ethos of millennials. Hence, in this study, an attempt has been made to understand the perceptions of millennials towards the brand activism bandwagon in India.

1. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK AND REVIEW OF LITERATURE

The marketing and advertising field has been witnessing a new phenomenon of “brand activism.” This is a new phenomenon wherein companies and brands assume activist mode and openly express their opinion about a cause or issue, and this is called as “brand activism” (Kotler & Sarkar, 2017). There are many corporates and brands who voluntarily assumes the activist role and support controversial issues and causes like abortion, gun control, same gender marriage, rights of gender minorities and immigration (Garfield, 2018). The rush of brands and companies towards the brand activism bandwagon has created lots of interest for inquiry into the field of marketing and advertising communications (Clemensen, 2017). Therefore, in this section, an attempt has been made to critically review, synthesize and find out the gaps in the literature related with the brand activism and millennials.

1.1. Millennials and brand activism

The generation born from 1980 to 2000 sharing the same attitudes, ethics, moral codes, and characteristics are called millennials (Bolton, Parasuraman, Hoefnagels, Migchels, Kabadayi, Gruber, Loureiro, & Solnet, 2013). The millennials are considered as a valuable and lucrative customer base because of their high spending power and high spending years ahead of them (Twenge, 2006) and they are also known for influencing the purchase decisions of their parents too. (Fromm & Garton, 2013). It was observed from the empirical studies across the world that millennials have higher expectations from the brands and companies that are trying to work for the welfare of the society (Waddock, 2008) and cause marketing and brand activism are one of the best ways to reach out to the millennials (Peloza & Shang, 2011). Millennials being more civic-minded and responsible than the older generations will feel onus is on them to make the world a better place to live. Hence, they tend to like and promote the brands and companies, which promote and support the causes and issues (Cone Inc., 2006). Millennials increasingly expect companies to be more socially responsible and act beyond their commercial interests (Steckstor, 2012). Millennials prefer and support the companies and brands that assume and promote the social responsibility than those brands and companies, which are just focused on profit (Carroll, 2008).

Millennials are used to advertising clutter and are more marketing savvy, unlike the older generations. Their skepticism makes them to judge the tall claims made by the brands rationally. Because of their increased and heightened sense of awareness, they frown upon the deceptive marketing strategies. As a result, millennials value honesty and transparency in the marketing and advertis-

ing communications of brands (Bergh & Behrer, 2013). They increasingly expect companies to be more socially responsible and act beyond their commercial interests (Steckstor, 2012). Millennials prefer and support the companies and brands that assume and promote the social responsibility than those brands and companies, which are just focused on profit (Carroll, 2008). There is empirical evidence to showcase that the companies’ and brands’ investments in corporate social responsibility and activism result in positive influence on marketing outcomes and grant the competitive advantage for business and purchase intention (Negrao, Mantovani, & Andrade, 2018). Such investments in corporate social responsibility and activism even result in purchase intention (Chang & Cheng, 2015) and increase in willingness to buy (Becker-Oslen et al., 2006) and brand image promotion (Du, Bhattacharya, & Sen, 2007) and perception of better product performance (Chernev & Blair, 2015).

The Edelman Earned Brand Global Report (2018) found that new-age consumers are more ethical and value driven. As a result, most of them do not hesitate to boycott or switch the brand if its stand on certain cause or issue upsets them. This kind of boycotting or brand switching behavior is more seen amongst the middle-class buyers. Peters and Barletta (2005) found that socially conscious consumption can also be applied and witnessed in both genders. The study conducted by Kim and Johnson (2013) also approves the same.

There are studies, which indicate that men and women behave differently to the cause of activism by the brands and companies. It was revealed that women are more interested and favorable for cause-related marketing than men. They hold more favorable attitudes towards the campaign format and indicate higher purchase intention (Cheron, Kohlbacher, & Kusuma, 2012; Moosmayer & Fuljahn, 2010). This gender difference is because of their differences in their values, attitudes and behaviors imposed on them by the society (Moosmayer & Fuljahn, 2010).

Hence, considering the review of the related literature on millennials manifesting activism, the following hypotheses were suggested and tested for the present study.

H1: Millennials recognize and prefer to buy brands that actively invest in manifesting activism.

H2: The liking for activism driven brands spans across genders amongst millennials.

H3: The liking for activism driven brands spans across different income levels amongst the millennials.

H4: Millennials associate themselves with brand even if it raises the price to stand for a greater purpose and values.

1.2 Brand activism, backlash and millennials

Brand activism is when a company or brand takes plunge into the social, cultural, gender, environmental issue and supports the same in its marketing and advertising communication to the society. In their rush to support a cause and attract the value and ethics driven consumers, they may stretch their activism part too far and may not be able to connect with the audience and are seen as a mere marketing gimmick. On the other hand, if it is done properly, it may cultivate the sizeable section of value and ethics driven consumers to their core consumer base. Therefore, it becomes imperative that companies and brands should acquire extensive knowledge about consumer behavior towards cause-related marketing and brand activism, before they jump into the bandwagon of brand activism (Solomon, Bamossy, Askegaard, & Hogg, 2010). Millennials are more aware and informed about the contemporary issues and problems and are more influenced by them because of their exposure to the digital medium and internet (Farment, 2012). Moreover, millennials are more marketing savvy and exposed to the plethora of advertisements with unrealistic brand promises, making them skeptical towards the tall claims made by the brands and companies. In this context, the brands and companies engaging in activism face the danger of being perceived as fake and may alienate the consumers (Garfield, 2018). Not always consumers will be impressed by the activism mode of the brands, sometimes they may refuse to admit the merit of brands espousing a controversial issue in political, social, cultural, and environmental spheres (Carr, Gotlied, & Shan, 2012). In contrast, if the brand activism resonates with the personal values of the consumer, it may result in boycotting where by buying the company product or service, the consumer shows his support for brand’s stand on controversial issues (Basci, 2014).

Copeland (2014) argues that boycotting is a mass and group activity and boycotting is more individualistic in nature. It was also observed empirically that both categories of consumers (boycotters and buycotters) differ in their demography and personality traits. It is also empirically proven that the buycotters are more optimistic and have more trust in business than the boycotters.

Baek (2010) found that if consumers like a product, they reward it by boycotting and if they do not like a brand, they will punish by boycotting the brand depending upon the social cause, political, and ethical cause the brand is espousing and connected with. Carrigan and Attalla (2011) found that sometimes consumers may overlook the factors like price, quality, brand familiarity and brand loyalty and may punish the unethical behavior of a brand, by resorting to boycotting and rewarding by boycotting for their ethical behavior. The main reason for backlash of consumers against the activism by the brands is to make company or brand to realize their unethical behavior and consequent unhappiness of the consumers (Klein, Smith, & John, 2004). In order to make that difference and bring a change, consumers may initiate boycotting actions to punish a firm or brand for its illegitimate or socially irresponsible actions or policies (Gardberg & Newburry, 2009).

Though, brand activism triggers buycotting behavior among consumers by positively affecting their attitudes and purchase intentions (Kam & Deichert, 2017), but there are flip sides to it, if activism of the brand falls short if it seen as a gimmick. The failed campaign of activism of brand and resultant boycotting of the brand may result in decrease in sales, cash flow and stock prices (Farah & Newman, 2009) and may affect the reputation or image of the brand (Klein, Smith, & John, 2004) and can negatively affect consumers’ attitudes towards the company and cause decrease in purchase intentions (Klein, Smith, & John, 2003). Hence, considering the above mentioned review of studies, the following hypotheses have been drafted and tested in this study.

H5: Fake and insincere brand activism triggers backlash among the millennials.

H6: Millennials feel that the brands should add their business voice to socio-cultural, political and environmental causes.

1.3. Aim

The study adds to the deeper understanding of the brands which choose to state their stand on social, political, environmental and cultural issues to target and impress the millennials. It also aims to investigate the perception of millennials towards the phenomenon of brand activism in India and its business implications so that brand managers can learn valuable lessons from the findings from the study. This research investigates the set of attributes the companies are expected to demonstrate more deliberately than they have recently in order to join the community of trusted corporations making the words “responsible” and “sustainable” to become inseparable. It would help the brand managers to effectively navigate the brand activism campaigns amidst the backlash from the dissatisfied and annoyed customer base amongst the millennials.

2. METHODOLOGY

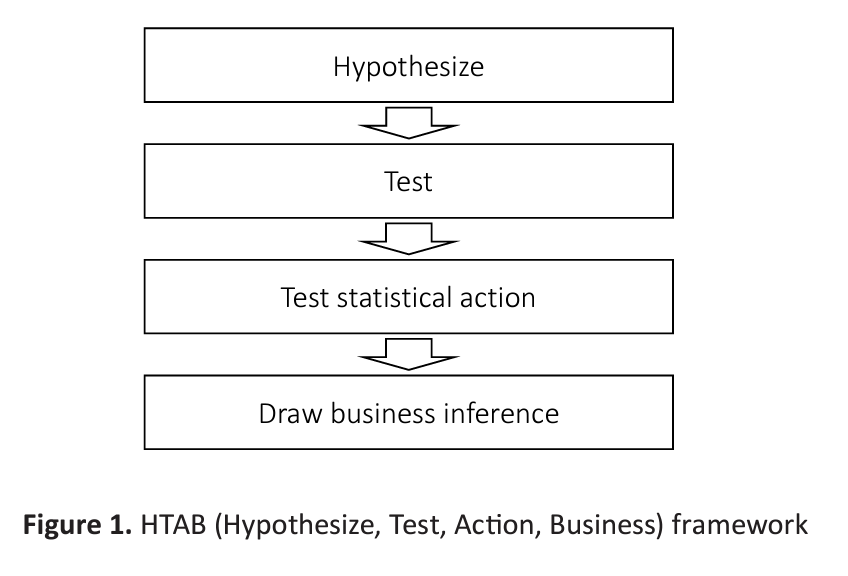

The methodology followed is HTAB (Hypothesize, Test, Action, Business), a popular analysis framework given by Ken Black in his book titled “Business Statistics: Contemporary Decision Making (6th ed.).” A high-level view of the framework is depicted in Figure 1.

The methodology involved six stages and they are as follows. The first three stages are related to objectives, problem statement, and the hypothesizing of the problem. The stages four through seven are related to data collection, analysis, testing the assumptions with appropriate techniques, and drawing valid business inferences:

- purpose of the study;

- problem statement;

- frame of the hypotheses;

- collection of data;

- data analysis

2.1. Purpose of the study

The purpose of the study is to understand the perception of millennials towards the phenomenon of brand activism in India and its business implications so that brand managers can learn valuable lessons from the findings from the study.

2.2. Statement of the problem

Brands in their overenthusiasm and exuberance tend to overstep in their pursuit of causes and issues to be associated with and to attract the particular segment of the customer base. In such overenthusiasm to promote a cause, they may enter into unfamiliar territories where their brand ethos and values do not find any sync with the cause they are supporting or identified with. During such situations, brands may be perceived as the champions of fake cause and resorting to gimmicks and may alienate the very customer base, whom they try to impress. Therefore, this research intends to study the perceptions of millennials towards brand activism, so that the findings from the study can help the brand managers to steer their brands in the troubled waters of brand activism.

2.3. Hypotheses

Based on the extensive review of related literature, the following hypotheses have been set and tested in this study.

- Millennials recognize and prefer to buy brands that actively invest in manifesting activism.

- The liking for activism driven brands spans across genders amongst millennials.

- The liking for activism driven brands spans across different income levels amongst the millennials.

- Millennials associate themselves with brands even if it raises the price to stand for a greater purpose and values.

- Fake and insincere brand activism triggers backlash among the millennials.

- Millennials feel that the brands should add their business voice to socio-cultural, political and environmental causes.

3. DATA COLLECTION

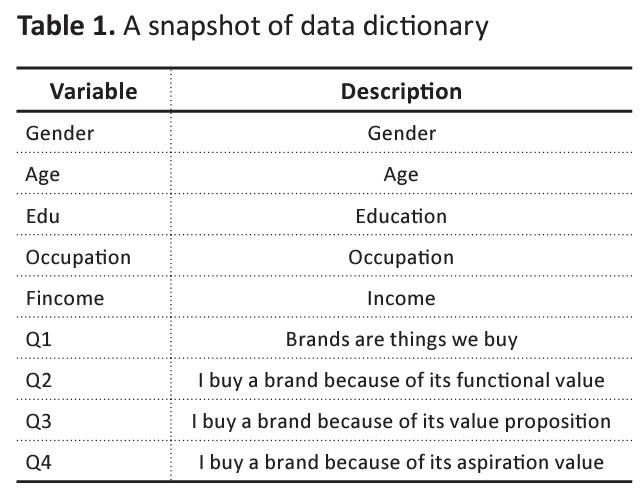

The data collection process involved identifying the target audience and sample size estimation. A sample comprising of 286 respondents was collected. The survey involved collection of demographics and attributes related to consumer perception on a five-point ranking scale. The final data had 286 observations and 45 features across seven categories, namely demographics, need, perceptions, reasons, value creation, buying behavior, and reasons for failure, respectively.

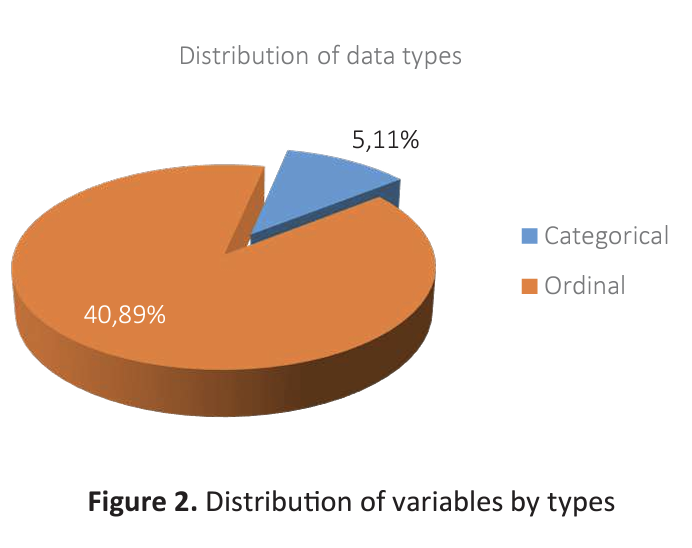

After data preparation, the final data comprised of 286 observations and 45 features with 40 features measured on ordinal scale and the remaining 5 features being categorical and each row corresponding to one respondent.

3.1. Data analysis and interpretation

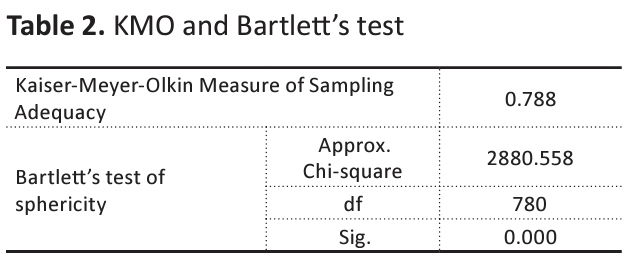

In data analysis stage, the features were subjected to Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) which involved extraction of latent structures in the data. The data were first tested for sampling adequacy and possible correlations. The KMO test reveals sampling adequacy, as the KMO value is much above the cut-off value of 0.78. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity is significant and thus establishing factorizability of the variables. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity checks whether or not there exist sufficient correlations amongst the manifest variables, which is a prerequisite to perform principal component analysis and factor analysis.

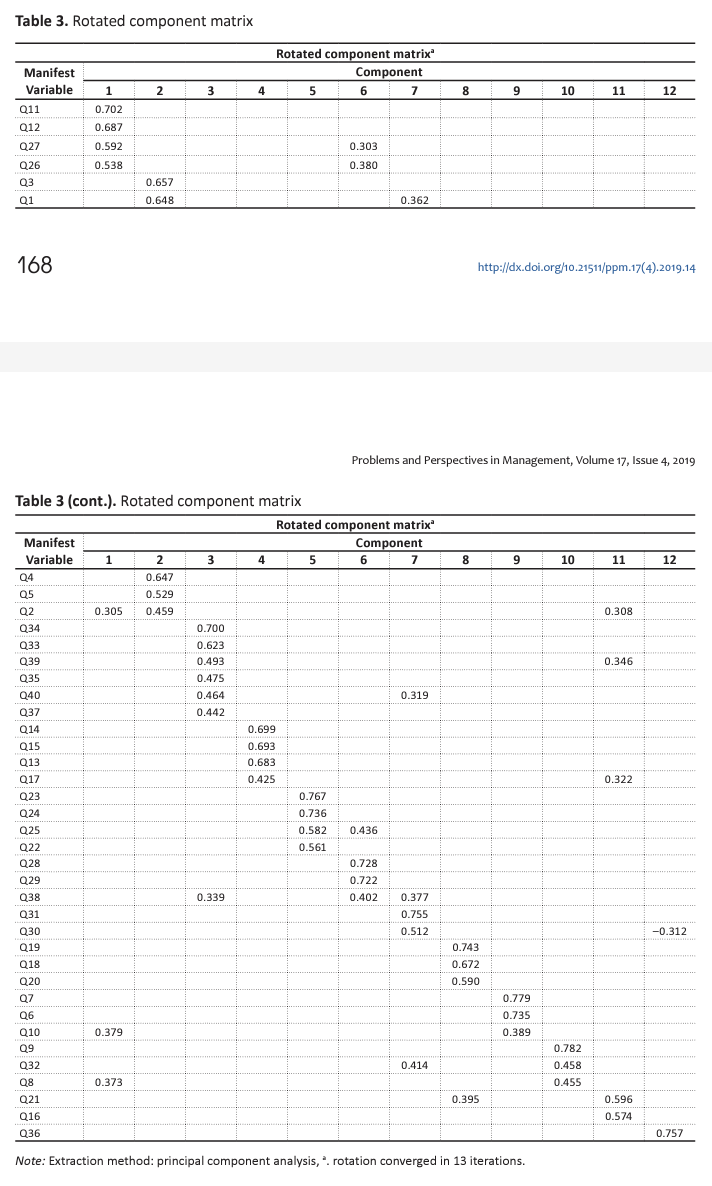

After data fitment study with KMO and Bartlett’s tests, factor analysis was performed to understand the hidden data structures. Twelve components were extracted, which explained around 60% of the total variation. Table 3 illustrates the rotated component matrix with factor loadings. Factor loading is the magnitude of correlations between the extracted components and the manifest variables.

The next step was to score each response to “positive” and “negative” based on average criteria The median score was generated for the records and the score strictly greater than 3 was classified as “positive” and rest as “negative.” This way a dichotomous response variable was created for the dataset.

Table 4. Distribution of brand activism response

Row labels | Number of respondents |

Negative | 71 |

Positive | 215 |

Grand total | 286 |

Now it is easier to classify a respondent with “positive” or “negative” towards brand activism with appropriate classification techniques, which is currently beyond the scope of this paper. Classification models like logistic regression, к-nearest neigbors and random forest can be fitted to predict whether or not a person has positive attitude towards brand activsm.

4. RESULTS: HYPOTHESES, TEST AND ACTIONABLE INSIGHTS

In the analysis, the perception of millennials towards the brand activism was measured by using the pearson Chi-square and factor analysis. The results are as follows.

5. DISCUSSIONS

The main objective of the research paper is to ascertain the perception of the millennials towards brands sermonizing and getting into the activist role. Based on the results mentioned in Table 5, it can be safely said that there exists a possible association between millennials and their preferences for brands, which manifests brand activism. The higher Chi-square value and p-value in Table 5 suggest the rejection of null hypothesis. The results demonstrate the fact that millennials prefer to buy a brand if it supports a cause or purpose in accordance with the brand ideology and personality when compared to the non-activist brands. The influence of activism of the brands on the purchasing behavior of the millennials is also covered in the previous studies and they also corroborates the above mentioned finding related with hypothesis 1 (Carroll, 2000; Negrao, Mantovani, & Andrade, 2018; Chang & Cheng, 2015). The managerial implication of the finding is that millennials are socially, culturally, politically and environmentally more conscious than the older generations and it pays for the brands to adopt activism to engage, attract, and retain the millennials.

The other objective of the paper is to find out the gender differences in the perception of millennials towards the brand activism, as they are exposed to the different kinds of agents of consumer socialization. The results mentioned in Table 6 notify that the perception of the millennials towards activism is independent of the gender. The high Chi-square and p-values greater than the significance level of 0.05 indicate that irrespective of their gender, millennials feel the same towards brands adopting the activism route. On the contrary, there are some empirical studies (Cheron, Kohlbacher, & Kusuma, 2012; Moosmayer & Fuljahn, 2010; Peters & Barletta, 2005; Kim & Johnson, 2013), which exposed the gender differences between the millennials in their perception towards activism, as women are more likely to be more interested and influenced by activism driven brands than the men. However, the implication of this finding is that activist brands need to build, nurture, sustain, and engage the millennials irrespective of the gender.

This paper also intended to examine the kind of association between income level of the millennials and their perception towards brand activism. The results shown in Table 7 and the high Chi-square and p-values confirm that the perception of millennials is not influenced by their income levels, hence, the null hypothesis is rejected. The managerial implication of the finding is that brand managers should engage, nurture, and embrace the millennials across the income categories, as their perception towards activism is not motivated or influenced by their levels of income.

Various empirical studies conducted across the world revealed that millennials are sensitive to the causes, which are closest to their heart and they will support and promote the activist brands at any cost. Hence, this study wanted to test whether the millennials are willing to pay higher price for activist brands to promote the cause or not. The results in Table 8 illustrate that millennials are willing to pay higher price for the activist brands in order to support the cause or purpose closer to their heart. The high Chi-square and p-values greater than alpha 0.05 in Table 8 suggest the rejection of null hypothesis. The relevance of this finding for the brand managers is that the emotional bonding of millennials is price inelastic and they are readily willing to pay the premium price for the activist brands.

This study also wanted to measure the perception of millennials towards acts of ‘fake brand activism’ wherein brands enter into the social, cultural, economic and environmental issue just to garner the attention and resorts to the marketing gimmick. The results shown in Table 9, especially the higher factor loadings in the table, validate the fact that fake and insincere activism results in the backlash of millennials. This finding is in resemblance to other studies (Garfield, 2018) wherein it was found that millennials exposed to the fake, unrealistic and tall claims of the activist brands make them more skeptical and may result in the boycotting of such activist brands. Hence, the relevance of this finding for the brand managers is that brands cannot just get into the activist role just for the sake of publicity and controversy, as such misadventure will invite backlash and boycott from the millennials.

The marketing literature is pulsating with the idea that millennials are more socially, culturally, environmentally conscious than their older counterparts and they believe that business in general and activist brands in particular should add voice to promote such causes. Therefore, the last objective of this study is to probe this phenomenon related with the millennials in the context of activist brands and their activism. The results in Table 10, especially the high Chi square andp-value, suggest the rejection of null hypothesis, indicating that millennials strongly feel that brands should add their voice to the contemporary social, cultural, economic, political and environmental causes to give back to the society. They feel that activist brands are more socially conscious and ethically responsible and such brands should be promoted and supported for the causes they espouse. Similarly, Basci (2014) found that brand activism resonates with the personal values and ethics of the millennials, leading either to boycotting or buycotting of the activist brands. Whereas, Carr, Gotlied, and Shan (2012) suggest that millennials may not always be impressed by the activism mode of the brands, sometimes, they may refuse to admit the merit of brands espousing a controversial issue in social, political, cultural, ethical and environmental milieu.

5.1. Findings of the study

Based on the analysis and interpretation of the data, the following findings are attributed to the study:

- Millennials prefer to purchase a brand if it supports a cause or purpose and they continue to buy a brand if it benefits a cause or people in need. At the same time, they stop buying the brand if it behaves unethically.

- There is no gender difference amongst the millennials in their perceptions towards brand activism.

- Millennials across different income categories have similar perceptions towards brand activism.

- The emotional tie of the millennials with the activist brands is price inelastic.

- It was found that brands taking a political stance, cherry-picking of issues and being disruptive prompts and create profound backlash.

5.2. Managerial and business implications of the study

The following are the managerial and business implications of the study:

- This study provides important insights about brand activism targeted at millennials and provides lots of insights into the brand managers who are increasingly spending much of their budget on brand activism campaigns targeted at millennials.

- It would help the brand managers to understand the likes and dislikes of millennials towards the phenomenon of brand activism.

- It would help the brand managers to wisely choose the themes, issues, causes and subjects, which are closer to the heart and mind of millennials.

- It would help the brand managers to effectively navigate the brand activism campaigns amidst the backlash from the dissatisfied and annoyed customer base amongst the millennials.

5.3. Limitations of the study

The limitations of the study are as follows:

- This study is limited to only millennials.

- This study is only limited to the geographical area of Bangalore City.

- This study is based on a limited sample of 286 respondents.

5.4. Scope for future research

This study is based on a convenience sample, which might bias the research towards certain types of respondents. Future studies should be extended to more specified target groups and can focus on several other issues on brand activism potential to benefit the society that remains to be addressed.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of the study and discussion in sections 4 and 5, it can be inferred that millennials, irrespective of their gender and income levels, always welcome brands, which add voice to the social, cultural, political and environmental causes than the brands, which choose to remain silent or neutral. Hence, for brands, especially those brands aimed at millennials do not have the luxury of being neutral or indifferent, but they have to take a stand and initiate meaningful and impactful action. The results and findings of the study also proved the fact that millennials even do not hesitate to pay the premium price for such activist brands, as their emotional bonding with such brands goes beyond the price logic. Therefore, it becomes imperative for the brand managers to start thinking strategically towards activism and navigate their brands carefully in the turbulent waters of activism, demonstrating brand’s core values and sincerity towards the cause they champion.

REFERENCES

- Anuar, M. M., & Mohamad, O. (2012). Effects of Skepticism on Consumer Response toward Cause-related Marketing in Malaysia. International Business Research, 5(9), 98-105.

- Baek, Y. M. (2010). To Buy or Not to Buy: Who are Political Consumers? What do they Think and How do they Participate? Political Studies, 58, 1065-1086.

- Basci, E. (2014). A Revisited Concept of Anti-Consumption for Marketing. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5(7), 160-168.

- Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The Impact of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46-53.

- Bergh, J., & Behrer, M. (2013). How Cool Brands Stay Hot: Branding to Generation Y. Kogan Page, London.

- Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why and How Consumer respond to Corporate Social Initiatives. California Management Review, 47(1), 9-24.

- Bolton, R. N., Parasuraman, A., Hoefnagels, A., Migchels, N., Kabadayi, S., Gruber, T., Loureiro, Y. K., & Solnet, D. (2013). Understanding Generation Y and Their Use of Social Media: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Service Management, 24(3), 245-267.

- Carr, D. J., Gotlieb, M. R., & Shah, D. V. (2012). Examining overconsumption, competitive consumption, and conscious consumption from 1994 to 2004: Disentangling cohort and period effects.

- Carrigan, M., & Attalla, A. (2001). The Myth of the Ethical Consumers – Do Ethics matter in Purchase Behavior? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18 (7), 560-577.

- Carroll, A. B. (2008). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Corporate Social Performance (CSP). In R. W. Kolb (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society (pp. 509-517). SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. SAGE Publications.

- Chang, C. T., & Cheng, Z. H. (2015). Tugging on Heartstrings: Shopping Orientation, Mindset, and Consumer Responses to Cause-Related Marketing. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(2), 337-350.

- Chen, J. (2010). The moral high ground: Perceived moral violation and moral emotions in consumer boycotts (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, United States.

- Chéron, E., Kohlbacher, F., & Kusuma, K. (2012). The effects of brand-cause fit and campaign duration on consumer perception of cause-related marketing in Japan. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(5), 357-368.

- Clemensen, M. (2017). Corporate political activism: When and how should companies take a political stand? Unpublished master’s project, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, Minnesota.

- Cone Inc. (2006). The 2006 Cone Millennial Cause Study: The Millennial Generation: Pro-Social and Empowered to Change the World. AMP Agency, Cone Inc,

- Copeland, L. (2014). Conceptualizing Political Consumerism: How Citizenship norms differentiate Boycotting from Buycotting. Political Studies, 62(S1), 172-186.

- Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2007). Reaping Relational Rewards from Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Competitive Positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(3), 224-241.

- Edelman Earned Brand Global Report (2018). A Study of How Brands Can Earn, Strengthen and Protect Consumer-Brand Relationships.

- Farah, M. F., & Newman, A. J. (2010). Exploring Consumer Boycott Intelligence using a Socio-Cognitive Approach. Journal of Business Research, 63(4), 347-355. Journal of Business Research, 63(4), 347-355.

- Fromm, J., & Garton, C. (2013). Marketing to Millennials: Reach the Largest and Most Influential Generation of Consumers Ever. AMACOM, American Management Association.

- Gardberg, N. A., & Newburry, W. (2009). Who Boycotts Whom? Marginalization, Company Knowledge, and Strategic Issues. Business & Society, 52(2), 318-357.

- Garfield, L. (2018). Gun-control activists aren’t backing down on a boycott of Apple, Amazon, and FedEx-here’s how it could affect sales. Business Insider.

- Kam, C. D., & Deichert, M. A. (2017). Boycotting, buycotting, and the Psychology of Political Consumerism (Paper presented at the 2016 Annual Meetings of the Midwest Political Science Association). Chicago, IL.

- Klein, J. G., Smith, N. C., & John, A. (2003). Exploring Motivations for participation in a Consumer Boycott. In S. Broniarczyk & K. Nakamoto (Eds.), Advances in Consumer Research (pp. 363-369). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

- Klein, J. G., Smith, N. C., & John, A. (2004). Why We Boycott: Consumer Motivations for Boycott Participation. Journal of Marketing, 68(3), 92-109.

- Kotler, P., & Sarkar, C. (2017). Finally Brand Activism! The Marketing Journal.

- Mantovani, D., de Andrade, L. M., & Negrão, A. (2017). How Motivations for CSR and Consumer-Brand Social Distance Influence Consumers to adopt Pro-Social Behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 36, 156-163.

- Moosmayer, D. C., & Fuljahn, A. (2010). Consumer Perceptions of Cause Related Marketing Campaigns. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27(6), 543-549.

- Neilson, L. A. (2010). Boycott or Buycott? Understanding Political Consumerism. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 9(3), 214-227.

- Parment, A. (2012). Generation Y in Consumer and Labour Markets: Routledge, New York, NY: Routledge.

- Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How Can Corporate Social Responsibility Activities Create Value for Stakeholders? A Systematic Review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117-135.

- Solomon, M., Bamossy, G., Askegaard, S., & Hogg, M. (2010). Consumer Behaviour: A European Perspective (4th ed.). Pearson Education Limited, Harlow.

- Steckstor, D. (2012). The Effects of Cause-related Marketing on Customers’ Attitudes and Buying Behavior. Gabler Verlag, Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag.

- Twenge, J. M. (2006). Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled – and More Miserable than Ever Before. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, S. M. (2008). Generational Differences in Psychological Traits and Their Impact on the Workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(8), 862-877.

- Waddock, S. (2008). Corporate Philanthropy. In R. W. Kolb (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society (pp. 487-492): SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.