Impediments to Environmental Education Instruction in the Classroom: A Post-Workshop Inquiry

Published: Jan. 10, 2007

Latest article update: Dec. 27, 2022

Abstract

Current research has begun to reveal a link between environmental education and increases in science achievement and understanding (Glynn 2000; Liederman and Hoody, 1998). The researchers in this study of participants in a coastal marine teacher workshop found that increases in environmental topics or lessons in teachers’ classrooms post-program were minimal. Several limitations to infusion were revealed, including teachers’ perceived obligation to strictly follow science standards, and an increased emphasis on preparation for standardized tests. The results suggest that greater emphasis is needed on providing opportunities for participants to make explicit connections with their instruction within the parameters of the science classroom.

Keywords

Professional Development, Environmental Education

INTRODUCTION

In the late 1960’s, stemming from increased environmental concerns and public activism, environmental education developed from the nature study, outdoor education and conservation movements. William Stapp’s definition of environmental education (EE) in the Journal of Environmental Education in 1969, outlined EE as a means of producing an environmentally literate citizenry, empowered and motivated to solve environmental problems.

However, over the past decade, research is beginning to reveal broad academic benefits of using the environment as a foundation for instruction. Multiple studies indicate a positive correlation between environmental education and student achievement. In the late 1990s, two studies conducted by the National Environmental Education Training .Foundation (NEETF) and Leidermann and Hoody (1998), formed the central foundation for the literature base illustrating the benefits of environmental education. These studies reported that EH can lead to increased knowledge and understanding of science content, concepts, processes and principles as well as increased problem solving and application skills. Furthermore, by linking academic topics to the local environment, students are able to make real-world connections, allowing the material to be made more meaningful, tangible and relevant. This increased relevance results in higher motivation, increased interest and decreased discipline problems (Battersby, 1999; Ernst & Monroe, 2004; Glynn, 2000; Krynock & Robb, 1999). These gains in student achievement and motivation are attributed to the nature of environmental education, which utilizes discipline integration, problem solving and hands-on activities (Glynn, 2000).

Linder the pressures of current reforms that focus on standards-based teaching and teacher accountability, teachers may lose sight of the value of environmental education. Although environmental topics may be integrated into various science disciplines, they receive very modest attention in the National Science Education Standards. Unaware of all the educational opportunities that environmental education presents, teachers may allow EE topics to be easily overshadowed by those that receive greater emphasis in national, state and local standards. In 1998, the National Environmental Education Advancement Program (NEEAP) conducted a study to determine the status of environmental education at the state level. Building on a Ruskey & Wilkes 1994 publication, Promoting Environmental Education, each state was asked to report on its status according to a survey that consisted of 16 components of a comprehensive environmental education program. Results of that survey indicate that there is much room for expansion of environmental education in the science curriculum.

One impediment to the infusion of environmental education (EE) into science curriculum may stem from the dearth of EE in teacher preparation programs. A study conducted by Rosalyn McKeown-Ice found that students of teacher training programs typically had limited access to environmental education content and methods, with fewer than one third of the institutions in her study offering students a background in environmental issues ( McKeown-Ice, 2000). Inadequate inservice opportunities are also a hurdle for infusing environmental education into classroom curriculum (Adams, Biddle & Thomas, 1988; Childress, 1978; Pettus & Teates, 1983). Not surprisingly then, many teachers express concerns about their competence to conduct EE programs (Buethe & Smallwood, 1986; NEEAC, 1996; Wade, 1996). In fact, insufficient teacher training has been cited to be the predominant reason K-12 teachers are not teaching H® (Gabriel, 1996).

Purpose and Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of the Rivers to Reefs/Coastlines (R2R) teacher workshop on teachers’ infusion of environmental topics into their curriculum. The University of Georgia has offered the R2R program each summer since 1999. However, evidence of the effects of the program on teacher instruction has been almost exclusively anecdotal, and very positive. This research aims to formalize the investigation in an effort to identify ways in which to maximize the impact of the program. The research questions guiding this study were:

In what ways are past participants of R2R integrating the environmental topics covered in the program into their instruction?

What limitations or barriers are perceived to hinder the integration of environmental topics in their curriculum?

Research Context and Methods

Description of the Workshop

The R2R program is a 15-day residential professional development program conducted by the University of Georgia at the Marine Education Center and Aquarium on Skidaway Island off the Georgia coast. R2R offers intensive lab and field experiences focusing on environmental issues of coastal marine ecology. These experiences are infused with and supplemented by instructional pedagogy appropriate for middle and high school students. Instruction frequently models inquirybased practices and teacher participants are given opportunities to develop lessons and labs that incorporate the topics covered in the program for use in their own classrooms.

Participants

Each summer, approximately 18 science education graduate students and teachers are admitted into R2R. Selection of the R2R participants is conducted by the two Project Directors, including a university-based science educator and professor and a site-based science educator and naturalist. Consideration is given in the selection process to allot 50% of the available slots to graduate students and the remaining portion to practicing teachers, with some participants fitting both categories. In addition, efforts are made to create a diverse pool of participants representing various levels and disciplines of secondary science and elementary instruction, years teaching experience, and school type (e.g, urban, rural, and suburban).

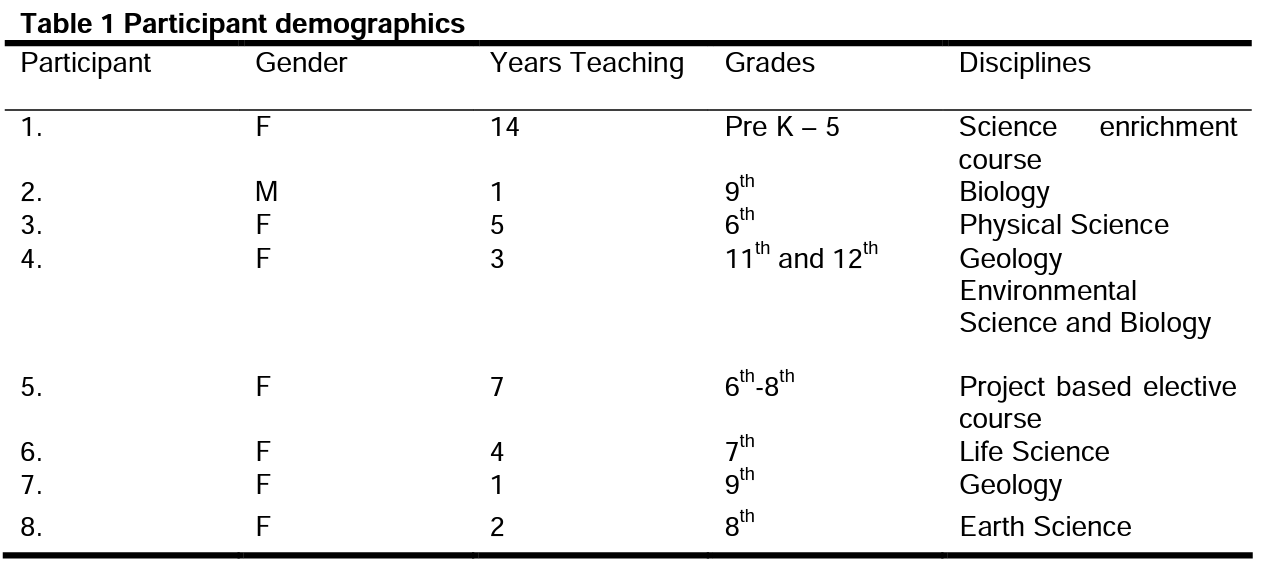

This study draws upon the interviews of eight past participants of R2R. Demographic information regarding the experience, discipline and grade level of each teacher participant is presented in Table 1.

Data Collection and Analysis

This research focused on qualitative interviews of eight past participants of R2R who are currently teaching. Interviews were conducted using a semistructured interview format, and the interviews were conducted at the schools of the participating teachers. Serving as an exploratory pilot study informing a larger research effort to investigate a wide range of effects of the program on participants, teachers were asked to reflect on their experiences in the R2R program as well as detail and provide examples of how it impacted their class instruction. Data were transcribed and analyzed from an interpretivist perspective (Crotty, 1998). Using open coding (Krathwohl, 1998), themes were identified and organized into categories. For the specific focus of this study, particular attention was given to activities the teachers reported to have utilized directly from the program, modified from ones offered or developed during the program, or lessons they constructed after participation that reflect environmental topics. In addition, participants were asked to discuss any obstacles they encountered when attempting to implement such activities.

Findings

Three main themes emerged from the interviews, each illustrating perceived limitations of the program’s usefulness, as well as barriers to implementing environmental topics in the classroom. The first theme reflected the teachers’ concern with strictly following content standards. The second theme encompassed the difficulty of translating the coastal experience into content that was meaningful to students. Finally, the last theme highlights the barriers the teachers perceived in teaching environmental education in a traditional school setting.

Following the Standards

Over the past two decades, educational reform has focused on the use of standards-based teaching. In 1996, the National Research Council established the National Science Education Standards to guide school science curriculum. Although not mandatory, the Standards serve as a blueprint for state and county standards. In 2001, President George W. Bush signed into law the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). One of the pillars of NCLB is teacher accountability, which measures student achievement against local standards through high-stakes standardized testing.

These interviews revealed that the teachers feel compelled to closely follow their schools’ established standards in an effort to adequately prepare their students for various tests each school administers in accordance with NCLB. In some of the situations, as many as three high stakes tests are administered each year, including the Iowa Test of Basic Skills, the Criterion Reference Competency Test, as well as a county exam that determines promotion to the next grade level. The teachers reported that preparation for these tests resulted in demands on time that did not allow for instruction of extra material. One teacher stated, “I am restricted and deluged with the curriculum I have, which does not allow a lot of time for integrating new materials or topics.” The perceived time constraints and limitations on freedom of curriculum were identified by almost all of the interviewed teachers as affecting their integration of R2R topics and materials in their classrooms.

Making the Connection

Part of the Rivers to Reefs program requires participants to generate activities for use in their classroom based on experiences and information from the program. This requirement provides participants with an opportunity to make connections with their classroom practice. In addition, teachers have the opportunity to collaborate with and gamer ideas from other teachers in the program, providing a rich resource for future lesson development particular to their class content. Despite this focused effort to tie the experience to classroom instruction, teachers reported only using their generated activities if it directly reflected one of the science standards for their content. The teachers seemed unaware of ways in which the environmental topics covered in R2R could be used to supplement instruction for other, perhaps seemingly unrelated, content standards. Materials from the program, such as posters or shells that were collected, were displayed in several of the classrooms. However, it was admitted that they were used mainly for decorative purposes.

In addition, several teachers felt that although the program was informative both in content and pedagogy, the information was limited in value because they did not teach on the coast. According to one teacher:

I really got a lot out of [the program] at the time. How much of it I use in my classroom is not much because, you know, we aren’t on the coast. We can’t really do a plankton lab or anything...[..] But as for the information, it isn’t really applicable to what I do.

This disconnect from the coast was salient in many of the interviews. Many of the teachers reported only drawing on their R2R experiences when teaching topics that were specifically covered in the program. Although a component of R2R provides direct connections of coastal issues to upstream activities, the teachers were unable to make the conceptual transfer of R2R topics to reflect their local environmental issues and ecology. This theme was more prominent with teachers who did not teach science disciplines that overtly align with environmental subjects. For example, the participant teaching physical science expressed that her use of R2R materials has been minimal because the “links to physical science are a little harder to come by”.

Environmental Education in the Traditional Classroom

The Rivers to Reefs program is based almost entirely on outdoor experiences . Participants conduct water quality experiments from the back of boats and coastlines are charted on foot using GPS equipment. Plankton tows conducted in the morning provide invertebrate samples for a lab investigation in the afternoon, and lessons about sea turtles are conducted at midnight on the beach while locating nests and tracks. The structure of the program seems to have influenced how these teachers think environmental education should be taught. )Each of the teachers discussed her/his desire to incorporate activities that immersed her/his students in learning within the environment

around them. However, this desire to provide similar experiences for their students was undermined by the perceived difficulty and obstacles to leaving the traditional classroom. One teacher remarked:

I’ve tried a few things, but it’s hard. You know we’re worried about security and the only door that is unlocked is the front office. You know, I have students that are allergic to bees. I have a student in the 6th grade that has a prosthetic leg. So there are things like that you have to take into consideration to do those things...

I had this fantasy that I would be able to bring my students to the coast and do those sorts of things that we put together. In reality, you can’t do that. We have lots of restrictions on field trips and a summer event like that is a headache in a lot of ways.

In fact, several of the teachers noted difficulties in trying to teach outside the classroom. Most frequently cited was the lack of funding and time available for field trips.

DISCUSSION

This study highlights some of the obstacles that undermine the effectiveness of the Rivers to Reefs workshop in increasing environmental education in science curriculum. Comments provided by teachers clearly indicate that they felt the program was a valuable one, offering inquiry experiences as learners, opportunities to collaborate with peer teachers, and instructional methods that can be used for any content. However, in regards to environmental content, much of what is purportedly gained in the program is not necessarily finding its way into classroom instruction.

In their work, Supovitz and Turner (2000), outline some characteristics of effective professional development. These characteristics include immersion of participants in inquiry questioning and experimentation through modeling of inquiry instruction, and the engagement of teachers in concrete teaching tasks based on teachers’ experiences with students (Aarons, 1989; McDermott, 1990; Bybee, 1993; Darling-Hammond & McLaughlin, 1995). In addition, professional development must center on subject matter knowledge, enhancing teachers’ content skills (Cohen & Hill, 1998; Kennedy, 1998). Grounded in established standards, professional development should be both intensive and sustained (NRC, 1996; Smylie, Bilker, Greenberg, & Harris, 1998; Hawley & Valli, 1999). Furthermore, for professional development to impact practice, the strategies must align with other aspects of school change (Fullan, 1991; Corcoran & Goertz, 1995, Lieberman, 1995).

Rivers to Reefs is designed to encompass these characteristics of effective professional development. The study conducted by Supovitz and Turner (2000) indicates that significant change in classroom practice occurs after 80 hours of professional development instruction. Rivers to Reefs, lasting 15 days in residence, well exceeds this benchmark. Built on a foundation of environmental content, participants are immersed in inquiry activities of various degrees and opportunities are provided to connect the materials with their classroom instruction.

In Supovitz and Turner’s outline of characteristics of effective professional development, as well as those provided by others such as Loucks-Horsley et al., (2003), each of the characteristics receives equal attention. This study, however, might suggest that greater emphasis should be given to those characteristics that provide clear and tangible links to classroom practice.

The need to provide effective environmental education professional development has been provided in the literature (Adams, Biddle, & Thomas, 1988; Bottinelli, 1976; Childress, 1978; Pettus & Teates, 1983). This study serves to contribute to our understanding of what characteristics and emphases maximize the impact of professional development on teacher instruction and ultimately student learning and achievement. Future research regarding R2R will provide a more in-depth investigation into the obstacles of teacher integration of environmental topics after participation in R2R, as well as identifying other impacts of the program on classroom practices.

REFERENCES

- Arons, A. B. (1989), What science should we teach? In the Biological Science Curriculum Study (Ed.), A BSCS Thirtieth Anniversary Symposium: Curriculum Development for the Year 2000 (p. 13-20).Colorado Springs, CO: BSCS

- Battersby, J. (1999). Does environmental education have ‘street credibility’ and the potential to reduce pupil disaffection within and beyond their school curriculum. Cambridge Journal of Education, 29(3), 447-459.

- Buethe, C. & Smallwood, J. (1986). Teachers’ environmental literacy: Check and recheck, 1975 and Journal of Environmental Education, 18(1), 39-42.

- Bybee, R. W. (1993). Reforming science education: Social perspectives and personal reflections. New York: Teacher’s College Press.

- Childress, R. (1978). Public school environmental education curricula: A national profile. Journal of Environmental Education, 9(3), 2-10.

- Cohen, D. K, & Hill, H. C. (1998). State policy and classroom performance: Mathematics reform in California. CPRE Policy Brief. Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

- Corcoran, T,, & Goertz, M. (1995). Instructional capacity and high performance. Educational Researcher, 24(9), 27-31.

- Crotty, Michael. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1995). Policies that support professional development in an era of reform. Phi Delta Карран, April 1995.

- Ernst, J. & Monroe, M. (2004). The effects of environment-based education on students’ critical thinking skills and dispositions toward critical thinking [Electronic version]. Environmental Education Research, 10(4), 507-522.

- Fullan, M. (1991). The new meaning of educational change. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Gabriel, N. (1996). Teach our teachers well: Strategies to integrate environmental education into teacher education programs. Boston: Second Nature.

- Glynn, J. L. (2000). Environment-based education: Creating high performance schools and students [Electronic version]. Washington, D.C.: NEETF. Retrieved May 18, 2005, from http://neetf.org/pubs/NEETF8400.pdf

- Hawley, W.D., & Valli, L. (1999). The essentials of effective professional development: A new consensus. In G. Sykes & L. Darling- Hammond (Eds.), Handbook of teaching and policy. New York: Teachers College.

- Kennedy, M. M. (1998). The relevance of content in inservice teacher education. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, April 1998. San Diego, CA.

- Krathwohl, D. (1998). Methods of educational and social science research: An integrated approach (2nd ed.) New York: Longman.

- Krynock, K. & Robb, L. (1999). Problem solved: How to coach cognition [Electronic version]. Educational Leadership, 57(3), 29-32.

- Lieberman, A. (1995). Practices that support teacher development. Phi Delta Kapp an, 76, 591-596

- Liederm an, G. A. & Hoody, L.L. (1998). Closing the achievement gap: LTsing the environment as an integrating context for learning. State Environmental Education Roundtable. Poway, CA: Science Wizards.

- Loucks-Horsley, S., Love, N., Stiles, K.E., Mundry, S., & Hewson, PW. (2003). Designing professional development for teachers of science and mathematics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- McDermott, L. C. (1990). A perspective in teacher preparation in physics and other sciences: The need for special science courses for teachers. American [ournal of Physics, 58.

- McKeown-Ice, R. (2000). Environmental education in the LTnited States: A survey of preservice teacher education programs. The [ournal of Environmental Education, 27(2), 33-39.

- National Research Council. (1996) National Science Education Standards. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Retrieved May 29, 2005from: http://www.nap.edu/readingroom/books/nses/html/1.html#why

- No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107— 110, 155 Stat. 1425 (2002). Retrieved May 20, 2005 from the LT.S. Department of Education Website: http://www.ed.gov/nclb/accountability/index.html?src=ov

- Pettus, A. M., & Teates, T.M. (1983). Environmental education in Virginia schools.Jouma/ of Environmental Education, 15(1), 17-21.

- Ruskey, A., Wilke, R. & Beasley, T. (2001). A survey of the status of state-level environmental education in the LTnited States — 1998 update. The [ournal of Environmental Education, 32(3), 4 - 14.

- Smylie, M. A., Bilcer, D. K, Greenberg, R. C., & Harris, R L. (1998). Urban teacher professional development: A portrait of practice from Chicago. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Diego, CA.

- Sparks, D. (2002). Designing powerful professional development for teachers and principals. Oxford, OH: National Staff Development Council.

- Supovitz. A., & Turner, H. M. (2000). The effects of professional development on science teaching practices and classroom culture, [ournal of Research in Science Teaching, 37(9), 963-980.

- The National Environmental Education Advisory Council (NEEAC). (1996). Report assessing environmental education in the LTnited States and the implementation of the National Environmental Education Act of 1990. A report prepared for Congress by the National Environmental Education

- Advisory Council, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Environmental Education Division, Washington, D.C. NEEAC.

- Wade, K.S. (1996). EE teacher inservice education: the need for new perspectives. Journal of Environmental Education, 27(2), 11-16.