Organizational culture and job satisfaction among academic professionals at a South African university of technology

Published: July 8, 2017

Latest article update: Dec. 10, 2022

Abstract

The South African higher education sector introduced structural changes, which resulted in the creation of universities of technology, (hereafter referred to as UoTs). There, however, has the not been any known studies that investigated organizational culture and job satisfaction among academic professionals at these new types of institutions in the country. This study’s main objective was to determine perceptions of organizational culture and their impact on job satisfaction among academic professionals at a University of Technology in the Free State Province, South Africa. The study’s respondents had positive perceptions of the organizational culture with academic professionals showing satisfaction with co-worker relations, supervision support and the work itself, as well as moderate satisfaction with the available advancement opportunities. Academic professionals were, however, dissatisfied with the salaries they were receiving. A significant correlation between overall organizational culture and job satisfaction was found

Keywords

Organizational culture, academic professionals, job descriptive index, job satisfaction, organizational culture profile

INTRODUCTION

The study of organizational culture and job satisfaction within the corporate world of the developed contexts has long intrigued scholars (Sempane, Reiger, and Roodt, 2002; Sabri, Ilyas, Amjad, 2011). An exploration of both phenomena has resulted in a better understanding of organizational life and reveals the complexities of everyday tasks and objectives in the workplace. The results of significant studies (Vukomjanski and Nikolic, 2013) on these two concepts have elevated these insights into significant elements of organizational theory (Macintosh & Doherty, 2010). The effects of the two concepts on outcomes including reduced turnover intentions (Salman, Saira, Amjad, Sana, and Muhammad, 2014) and on organizational performance in the developed world make the study of developing sectors such as the higher education sector, where there is still paucity of empirical evidence regarding the two phenomena imperative. Hence, this exploration of the relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction among academic professionals at a higher education institution in South Africa.

Brief context of the study

Research (Gazzola, Jha-Thakur, Kidd, Peel, & Fischer, 2011) has shown that changes in both the internal and external environments affect businesses in the corporate world and other sectors, such as higher education in the developing world. The global higher education sector is undergoing continuous changes due to expansions in student numbers, funding challenges, and program changes determined by national and international demands (Hazelkom, 2012). For example, the post-1994 dispensation in South Africa witnessed a new order in the higher education sector evidenced in mergers and incorporations of higher education institutions, which resulted in the formation of new comprehensive institutions, retention of some traditional universities, and the creation of Universities of Technology (UoT) (Chipunza & Gwarinda, 2010). A typical South African UoT offers industry-oriented or vocationally-oriented programs, where students undergo a six months to a year world of work experience under the ‘Work Integrated Learning Program (WIL)'. The institution under study underwent some changes with regard to: leadership, systems, procedures and processes, programs, student numbers, conditions of service, quality of staff, structures, in order to create a new university culture while maintaining the vocationally-oriented aspects. These changes introduced a new organizational culture and presumably impacted on the institution’s employees' job satisfaction. Organizational change theories (Gready, 2013; O’ Malley, 2014) argue that major changes, such as mergers and acquisitions, affect an organization’s core business, with the change to the core business in the higher education sector likely to affect academics (Timmins, Bham, McFadyen, and Ward, 2006). It is this context and observations drawn the above-cited scholars that formed the basis for our choice of academic professionals as units of analysis in the current study.

Theoretical framework

This study was based on the social exchange theory, which draws on social psychological and sociological perspectives that explaining behavioral and social changes as negotiated exchanges between parties (Greenberg & Scott, 1996; Zafirovski, 2005). The theory postulates that people make decisions based on their individual satisfaction levels within a social relationship. Thus, the process of change, which relates to perceptions of organizational culture, can be viewed as a social relationship in which the organization and employees negotiate exchanges that result in outcomes such as increased employee motivation and job satisfaction. This research postulates that, the perceptions of organizational culture, constituted from institutional transformation, and the resultant job satisfaction among academic employees, are social exchange outcomes as both constructs reflect a perception of the exchange quality (Van Knippenberg & Sleebos, 2006). Therefore, the study’s particular focus on the ways that the established organizational culture of the new institution’ impacts the academic professionals’job satisfaction.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.1. Organizational culture

The last decade witnessed the rise to prominence of organizational culture as an important concept in the business world. There are various definitions of the concept organizational culture, with Mohelska and Sokolova (2014), stating that the definition depends on the sector, the organization’s historical events, and the employees’ personalities and nature of interaction. It is variously defined as: a system of shared meaning held by members that distinguishes one organization from another (Robbins, 2001; Naicker, 2008); collective thinking, habits, attitudes, feelings and behavior patterns (Clemente, Greenspan, 1999); and a programmed way of perception derived from the beliefs and values (Sonja, Matjaz, & Monty, 2008). Organizational culture, in the context of this study, can be defined as “the shared values and beliefs of university stakeholders (i.e., administrators, faculty members, students, board members and support staff), developed in historical process and conveyed by the use of language and symbols” (Bartell, 2003, p. 5; Mohelska & Pitra, 2012).

Organizational culture impacts on how employees set personal and professional goals, perform tasks and administer resources in order to achieve set goals (Lok & Crawford, 2004, p. 3). Various researchers (Kono, 1990; Rue & Holland, 1986; Silvester & Anderson, 1999) use a variety of terms, methods and approaches to describe the components and characteristics of organizational culture. However, the shared meanings at the core of an organization’s culture are captured in key seven characteristics, which are innovation and risk taking, attention to detail, outcome orientation, people orientation, team orientation, aggressiveness and stability. Consequently, these organizational culture’s elements affect the way employees

consciously and unconsciously think, make decisions and the way they perceive, feel and act using shared meanings.

Innovation and risk taking play a significant role in organizational culture. Both are indicative of an organization’s openness to change, and ability to encourage employees to experiment and take risks (Delobbe, Haccoun & Vandenberghe, 2001). Innovation leads to improved orientation (Wilderom & Van der Berg), adaptability (Fey & Dension, 2003), high performance (Matthew, 2007), and job satisfaction (Bashayreh, 2009).

Attention to detail refers to the degree to which employees exhibit precision and analysis in their daily activities (Naicker, 2008, p. 7). Some organizational culture experts argue that the emphasis on innovation and aggressiveness compromises the attention to detail (Chow et al., 2001). Nonetheless, Bikmoradi et al., (2008) state that an organizational culture that de-emphasizes attention to detail engenders a negative response from employees. The newly created universities of technology in South Africa have a mandate to transform themselves into innovative and entrepreneurial hubs. As a result, the creation of such cultures, though plausible, also yields negative results such as dissatisfied employees (academics), especially those who fail to accept the unfolding changes.

An organization should be people-oriented and this involves the institution’s support, cooperation with and respect of employees (Delobbe, Haccoun & Vandenberghe, 2001). The management should facilitate an ongoing people-oriented organizational culture if the impact is to be felt by its workforce (Kulkami, 2010). This is evidenced in the example of the South Korean context, where a positive people-oriented culture offering respect for personal employee values leads to employee satisfaction and reciprocal responses of commitment (Choi, Martin & Park, 2008).

A team orientation culture, also a significant element of organizational culture, organizes work activities around teams (Naicker, 2008). Established teams deliver better results than individual efforts (Bauer & Erdogan, 2014). Furthermore, organizations that create teams based on employees’ complementary skills are more effective than those that do not (Robbins, Judge, Odendaal & Roodt, 2013). On the contrary, some research findings, such as Chow et al. (2001), found a moderate association between task-oriented cultures and outcomes in Chinese-based academic collective cultures. Nonetheless, these studies’ sample sizes were not aggregated, thus they do not sufficiently explore the extent of the impact of team orientation cultures on behavioral outcomes such as job satisfaction, among a cross-section of academic professionals.

A culture of aggressiveness, on the one hand, relates to a stability culture in which organizational activities emphasize status quo maintenance at the expose of growth. This culture often competes with cultures of aggression that are associated with an organization’s employees’ level of competitiveness (Naicker, 2008). In fact, aggression affects an organization’s sense of global competitiveness and survival techniques (Chow et al., 2001), as confirmed by Bauer and Erdogon (2014) and Castiligia (2006) in their findings on how academic faculty regarded aggressive cultures as the least preferred organizational culture. However, the ever-changing business environment requires that organizations, higher education institutions included, be organic and dynamic for their own survival.

Each of the above characteristics complement each other. Hence, there is a need to use to appraise South Africa’s universities of technology using these characteristics to get a composite picture of their current organizational cultures) and the academic employees’ perceptions on the culture and effect on job satisfaction (Naicker, 2008).

1.2. Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction contributes to an organization’s success (Saari & Judge, 2004). Beam (2006) defines job satisfaction as “the favorable viewpoint of the worker toward the different aspects of work role or job he/ she presently occupies”. Chiboiwa, Chipunza, and Samuel (2001) and Sempane, Rieger, and Roodt (2002, p. 25) regard job satisfaction as “the feeling that employees have about their job characteristics”. Thus, job satisfaction is a constellation of employees’ feelings about various job elements, and these relate to the intrinsic or extrinsic job elements. There are countless approaches that are used to classify job satisfaction dimensions, as outlined by Weiss et al. (1967), Cranny et al. (1992), and Moorman (1993). This study draws on the intrinsic-extrinsic approach postulated and recommended by Weiss et al. (1967), which includes psychological and physical aspects in the intrinsic-extrinsic classification in its consideration of the dimensions of job satisfaction. According to Sempane, Rieger & Roodt, (2002, p. 25) and Beam (2006, p. 170), a job and its characteristics, are associated with intrinsic satisfaction such as its content, autonomy, responsibility, achievement and variety, whereas the context of job performance is associated with the extrinsic elements, such as the salary, company policies, job security and work relationships (Herzberg, Mausner, & Snyderman, 1959). Brough and Frame (2004), and Saari and Judge’s (2004) study shows that similar satisfaction scores among employees do not suggest that they are all satisfied with all job factors. Thus, it can be assumed that academic professionals at higher education institutions may show the same score of satisfactions levels and yet there might be differences regarding particular aspects of job satisfaction that contribute[d] to each individual’s score. Therefore, our study assumes that an academic employee may be generally satisfied with their job, but not be satisfied with certain intrinsic or extrinsic facets of the job owing to their perceptions of organizational culture.

1.3. Relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction

Existing literature examining organizational culture and employees’ attitudes in higher education has not really focused on organizational culture as a determinant factor of job satisfaction. Various two-factor theory-based studies in the higher education context noted that job satisfaction is influenced by intrinsic-motivational factors, in particular academic autonomy, while job dissatisfaction is associated with extrinsic-hygiene factors, such as pay and conditions of employment (Pearson & Seiler 1983; Hill, 1986; Moses, 1986). This section reviews studies on organizational culture and job satisfaction in both the higher education settings in order to provide a context to this study.

The relationship between organizational and behavioral outcomes such as job satisfaction is significant. A study on the organizational supportive culture and job satisfaction in the Taiwanese higher education context carried out by Dian-Yan, Chia-Ching, and Shu-Hsuan (2014) underscores the halo effect of organizational commitment in the mediation of organizational culture and in affecting behavioral outcomes such as job satisfaction. Mabasa and Ngirande (2015) also found a positive relationship between organizational support and job satisfaction among academics in South Africa, with their study further differentiating male and female job satisfaction levels owing to the existence of a rotational culture that is supportive of staff. Although our current study does not determine male and female differences, it is prudent to assume that such difference exists within South African universities of technology.

Bashayreh’s (2009) study examining the relationship between the dimensions of organizational culture and job satisfaction in Malaysia’s higher education shows that there was no significant relationship between reward and the performance-oriented dimension of organizational culture and job satisfaction. The study, however, recorded a significant relationship between organizational culture factors such as organizational supportiveness, innovation and stability, and communication and job satisfaction. This raises the question on whether there is a direct linkage between organizational culture and job satisfaction in higher education. The question leads to Trivelas and Dargenidou’s (2009, p. 382) study on organizational culture and job satisfaction’s influence on the quality of services provided in higher education among faculty and administration members in Lisbon. The results indicated that specific culture archetypes are linked, through the job satisfaction of employees, with different dimensions of higher education service quality. For example, a hierarchy culture, most prevalent among faculty members, had a strong correlation service quality with job satisfaction moderating the relationship. Furthermore, Sabri, Ilyas and Amjad’s (2011, p. 121) study, which notes that organizational culture in Pakistan is categorized that related to managers and leaders (OCM) and another to employees (OLE), observed that the effect of both cultures on job satisfaction were positive and significant among faculty in both the public and private higher education institutions.

It is evident that organizational culture impacts on job satisfaction. However, studies on the new organizational cultures arising from the restructuring of South Africa’s higher education focused more on 2.2. Objectives and hypotheses aspects such employee engagement (Gay, 2012) and The objectives of the study drawn from the above conquality of teaching (Leibowitz, 2014) and not on or- ceptual framework, were to: (1) determine academic ganizational culture and its impact on issues such as professionals’ perceptions of organizational culture organizational culture, hence this study. (2) measure the job satisfaction levels of the academic professionals, and (3) determine the relationship between academic professionals’ perceptions of organizational culture and their job satisfaction.

2. PROBLEM STATEMENT

The University under study, which is named University X, for ethical reasons, was established in 2004 as a UoT, as part of higher education transformation in South Africa. The ‘new institution’ has undergone some changes in its operations and these have resulted in the creation of a new organizational culture. To the researcher’s knowledge, no study has been carried out to investigate the relationship between the newly created organizational culture and job satisfaction among academic professionals at the institution. In view of this, this study examines the impact of changes in the organizational culture of the university under investigation, by asking the following questions: (i) Since the establishment of University X, what perceptions do academic professionals have about organizational culture and job satisfaction? ii) Do the perceptions of organizational culture correlate with the levels of job satisfaction among the academic professionals?

2.1. Conceptual framework

The above-noted theoretical framework and literature review were used to develop a conceptual framework to illustrate the hypothesized relationships between academics’ perceptions of organizational culture and job satisfaction. The different elements of organizational culture are perceived to be related to either intrinsic or extrinsic job satisfaction of employees. For example, if the institution allows innovation and risk-taking among its academic professionals, it is assumed that they will develop intrinsic motivation (Lee & Chang, 2008), while promoting team and people oriented approaches are linked to the extrinsic motivation of the academic professionals (Griffin, Patterson & West, 2001). If the institution emphasizes stability and maintenance of the status quo, then academic employees will be negatively satisfied since an academic environment is one in which ideas and change are organic and evolving (Trivellas & Dargenidou, 2009).

It was hypothesized, with Ho and Ha representing the null and alternative hypotheses, respectively that: Ho - employees’ perceptions of the institution’s organizational culture will be positively correlated with their perceived job satisfaction; Ha - employees’ perceptions of the institution’s organizational culture will not be positively correlated with their perceived job satisfaction.

2.2. Research objectives

The research, which uses University X in the Free State Province of South Africa as a case study, investigated perceptions of organizational culture and their resultant impact on job satisfaction levels among academic professionals.

2.3. Research methodology

The mainly cross-sectional descriptive case study, adopted the quantitative approach and a positivist philosophical paradigm (Kumar, 2011), which emphasize empirical deductive reasoning and interpretation of figures to determine the standing of a sample of a given construct.

2.4. Population and sampling

The target population consisted of 274 full-time academic professionals from the selected institution. Their distribution across the faculties was: 84 Faculty of Engineering; 46 Health and Science; 70 Humanities, and 74 Management Sciences. Stratified proportional representation sampling was used to select the sample, with a sample calculator used to calculate the minimum required sample size. Thus, a determined sampling size of 160 full- time academics was established. A proportional selection system, where for every one academic professional from the Health faculty, two were picked in the Humanities, three from Management Sciences and four from Engineering, was used. The proportional stratified sampling method resulted in 16 academic professionals being randomly selected from the Faculty of Health, with 32 from the Faculty of Humanities, 36 from the Faculty of Management Sciences and 51 from the Faculty of Engineering. The actual sample used for the study was (n-135), representing 84% of the total population.

2.5. Data collection

A questionnaire divided into three sections, was used to collect data for this study. One section measured demographic variables such as gender, with the second, an adapted Organizational Culture Profile Questionnaire (OCP), developed by Reilly et al. (1991) having 28 items measured on a five point Likert scale form (1) not at all to (5) very much, and the last section adapted from the Job Descriptive Index (JDI) by Smith, Kendall, and Hulin (1969) seeking to measure the job satisfaction of the academic professionals. Permission to distribute the questionnaires was obtained from the institutional management and the distribution done by trained research assistants. The purpose of the study was explained to each respondent and participation was voluntary. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to determine the internal consistency of the scale items for each section. The scale items showed excellent internal consistency, as the alpha values were 0.95 for the OCP, and 0.96 for the JDI.

2.6. Data analysis

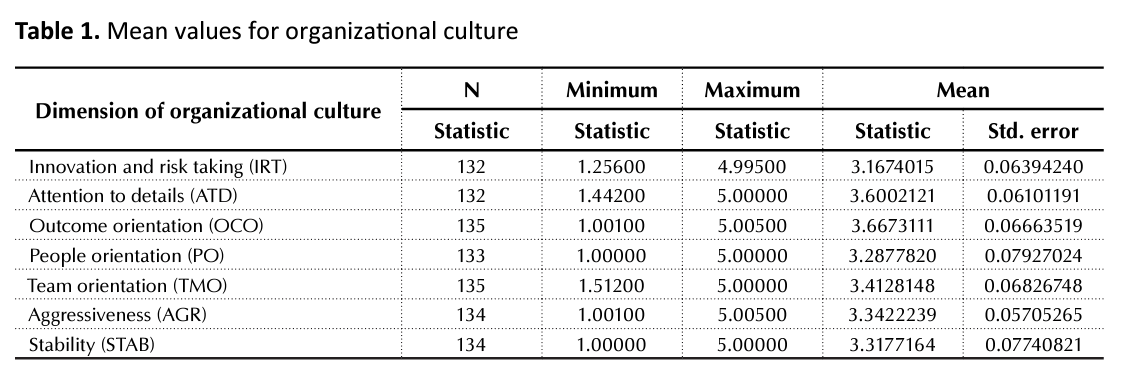

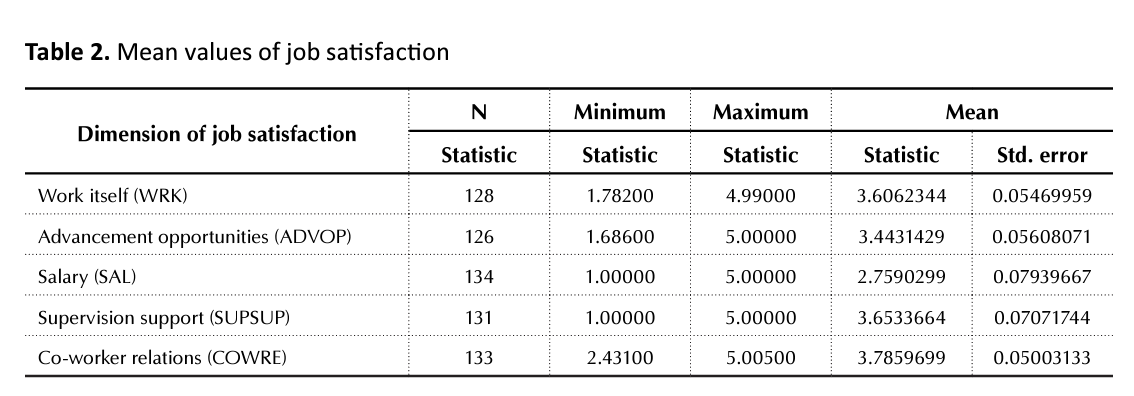

Decretive statistics data analysis was used to analyze demographic variables and test the study’s both hypotheses. Measures of central tendency, specifically the mean, were computed for hypothesis one and hypothesis two to determine the academic professionals’ levels of organizational culture and job satisfaction. The Likert scale was used to measure organizational culture measured items on a five- point scale ranged from: (1) not at all, (2) minimally, (3) moderately, (4) considerably and (5) very much. For job satisfaction, items were measured on a five- point scale ranging from; (1) very dissatisfied, (2) dissatisfied, (3) neutral, (4) satisfied and (5) very satisfied. In this regard, using measures of central tendency and dispersion provided in Table 1 and Table 2, a mean value of below < 3 indicates a negative inclination towards organizational culture or job dissatisfaction, whilst a mean value equal to or above > 3 indicates a positive inclination towards organizational culture or job satisfaction. The third hypothesis was tested using Pearson Moment Correlation method which measures the strength of agreement between two or more variables in social science research (Cohen, 1992).

3. THE STUDY’S RESULTS

3.1. Sample characteristics

The sample of academic professional who participated in the study had more males (57%) than females (43%). The distribution of age was close to normal, with the majority (24%) between 36 - 40 yrs. The other characteristics were: whites at 46.6% and the dominant race; the majority of academics (69.6%) married, and a Masters as the highest qualification among 66.7% of the sample.

3.1.1. Organizational culture

The study’s first hypothesis was that academic professionals have negative perceptions about organizational culture. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 1.

The table shows that academic professionals perceived the institution’s organizational culture as possessing a moderate character of team orientation (3.41), aggressiveness (3.34), stability (3.32), people orientation (3.29), and innovation and risk taking (3.17). Higher mean scores of organizational culture perceptions were found in the dimensions of: attention to details (3.60) and outcome orientation (3.67).

3.1.2. Job satisfaction

The study’s second hypothesis stated that academic professionals are not satisfied with their jobs.

As shown in Table 2, two of the extrinsic job satisfaction factors (co-worker relations and supervision support) had mean scores above 3, while that of salary was almost 3.

3.1.3 Organizational culture and job satisfaction

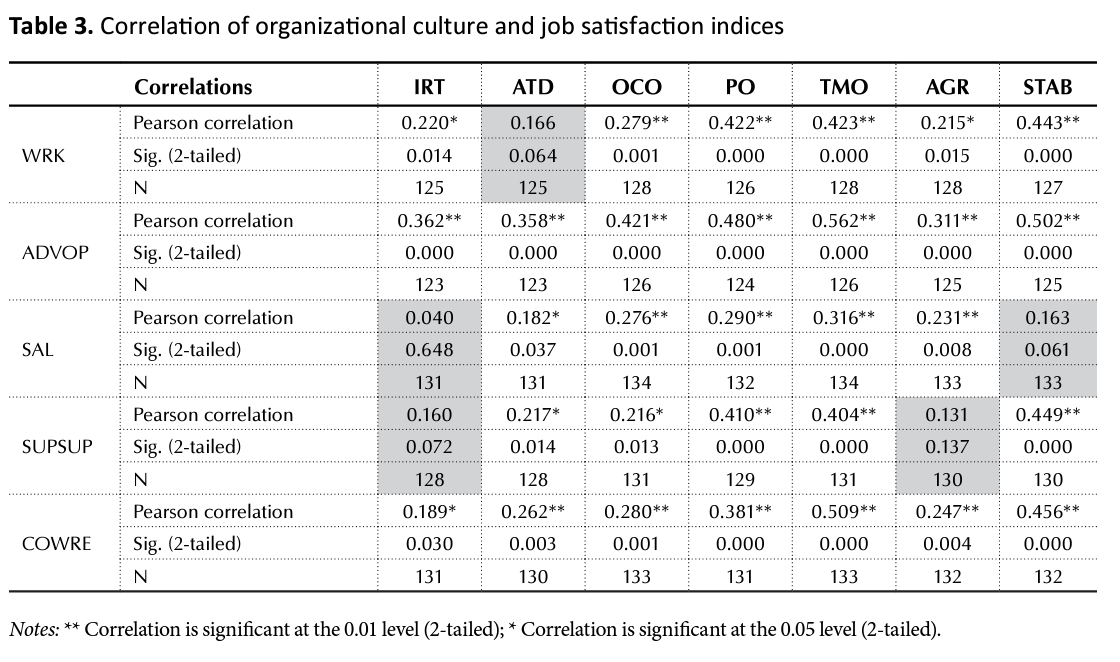

The third and fourth hypotheses stated that: (1) there is no correlation between organizational culture and job satisfaction, and (2) there is no correlation between specific components of organizational culture and specific job satisfaction components.

Table 3 demonstrates a positive significant correlation between most organizational culture and job satisfaction indices. There was a significant correlation between work itself and the following dimensions of ОС: innovation and risk taking (r - 0.014), outcome orientation (r - 0.001), people orientation (r - 0.000), team orientation (r - 0.000), aggressiveness (r - 0.015), and stability (r - 0.000). Further significant correlation between advancement opportunities with all the organizational culture characteristics, such as innovation and risk taking (r - 0.000), attention to details (r - 0.000), outcome orientation (r - 0.000), people orientation (r - 0.000), team orientation (r - 0.000), aggressiveness (r - 0.000) and stability (r - 0.000) is also noted. A significant correlation was found between salary and the following ОС dimensions, attention to details (r - 0.037), outcome orientation (r - 0.001), people orientation (r - 0.001), team orientation (r - 0.000), and aggressiveness (r - 0.008). There was a significant correlation between supervision support and attention to details (r - 0.014), supervision support and outcome orientation (r - 0.013), supervision support and people orientation (r - 0.000), and supervision support and stability (r - 0.000). Co-worker relations had a significant correlation with the organizational culture characteristics, innovation and risk taking (r - 0.030), attention to details (r - 0.003), outcome orientation (r - 0.001), people orientation (r - 0.000), team orientation (r - 0.000), aggressiveness (r - 0.004) and stability (r - 0.000). These correlations lead to the rejection of both hypotheses.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Perceptions of organizational culture

The results based on the hypothesis that academic professionals will have negative perceptions about organizational culture indicate that academic professionals had moderate positive perceptions of the organizational culture.

Outcome orientation had the highest mean score response of 3.67. This indicates that academic professionals at the institution under study perceived the institution’s culture as more focused on outcomes than the process used to achieve these outcomes. The present study’s high mean score confirms Dastmalchian, Javidan and Alam’s (2001, p. 540) findings from an Iran-based study that societal culture was characterized by a high level of outcome orientation effective leadership and culture in Iran. However, Bikmoradi, Brommels, Shoghli, Zavareh and Masiello’s (2008) study on medical school faculty members pointed out that there was insufficient support for the outcome orientation within the school. Similarly, Gray, Densten and Sarros’s (2003) study on organizational culture in small, medium and large Australian organizations, found that outcome orientation had the lowest mean score and was perceived as the least characteristic of organizational culture. Therefore, the present study adds to the existing literature by highlighting outcome orientation as the highest characteristic of organizational culture within a vocationally-oriented higher education institution found in a developing economy.

Attention to details had a high mean response score of 3.60. This indicates that academic professionals at the studied institution were of the view that the institution’s culture emphasized on employee precision and paying attention to detail in the workplace. Gray et al. (2003) found a moderate mean score for attention to details in a study done on executives’ perceptions on organizational culture in small, medium and large Australian organizations. Similarly, Chow, Harrison, McKinnon and Wu (2001) argue that much time and effort within organizations is directed towards innovation and aggression, which carries with it a reduced emphasis on attention to detail. This is confirmed in an observed medical school faculty members’ provision of insufficient support to paying attention to details noted by Bikmoradi et al. (2008). Although the high mean score for attention to details in this study is not consistent with previous studies, the present study’s results are unsurprising, considering that paying attention to detail is one of the virtues expected of any institution of higher academic learning.

The study results show that team orientation had a moderate mean score of 3.41. The result may be due to the institution’s academic professionals’ perceptions that the institution’s culture encourages teams than individuals. Organizations with a team-orientated culture are collaborative and emphasize cooperation among employees (Robbins, Judge, Odendaal, and Roodt, 2013). Kozlowski and Bell (2003) argue that organizations that stress a spirit of team work and collaboration can capitalize on the individual strengths of their employees, for the collective product is greater than the sum of the individual effort. Thus, the results could be justified, considering that one of the key responsibilities of academic professionals is lecturing, which can be regarded as an individual task. Conversely, this assertion would contradict the collegiality that is encouraged among academic professionals in areas such as research.

The moderate score on aggressiveness 3.340 showed in Table 1 refers to the degree of competitiveness in an organization (Naicker, 2008). Bauer and Erdogan (2014) explain that every organization lays down the level of aggressiveness with which their employees work. Greene, Reinhardt and Lowry (2004, p. 80) contend that organizations with aggressive cultures value competitiveness and often fall short in terms of corporate social responsibility. A Catholic college based study by Castiglia (2006) found that the faculty regarded aggressiveness as the least preferred organisational culture characteristic. Nonetheless, one may argue that aggressiveness is an organizational culture character mostly found in corporate organizations than in institutions of higher learning.

The stability factor had a moderate mean score of 3.32. This score means that the academic professionals perceived the institution’s culture as encouraging the maintenance of the status quo and not growth. Stability is associated with centralization, conflict reduction, conformity, consensus, consistency, continuity, control, formalization, hierarchy, integration, maintenance, order, security, status quo, and standardization (Burchell and Kolb, 2007). A study by Chow et al. (2001) states that stability as part of organizational culture, has a strong impact on affective commitment, job satisfaction and information sharing. Similarly, Bikmoradi et al. (2008, p. 424) in a study faculty members, found that the faculty participants from the research on a medical school emphasized on stability versus openness to change. Therefore, the moderate mean score obtained in the study for the stability factor can be understood within the context of the transformation agenda that the institution is currently promoting and championing.

People orientation had a moderate mean score of 3.29. People-orientated cultures value fairness, supportiveness, and respect for individual rights. The mean score indicates that the academic professionals were not sure whether the institution’s culture promoted criticisms from its members or was concerned with their personal problems and personal development. These results are consistent with the results from Dastmalchian et al. (2001), which noted a moderate emphasis on human orientation as a cultural attribute of Iranian society. Contrastingly, a study by Choi, Martin and Park (2008) focusing on organizational culture and job satisfaction in Korean professional baseball organizations found that the clan culture had a positive impact on employee satisfaction owing to its emphasis on personal values and respect for people.

Innovation and risk taking had a moderate mean score of 3.17. The obtained moderate mean score is consistent with that from a study by Gray et al. (2003) that found that the executives perceived innovation as a moderate character of their firms’ culture. According to Deutschman (2004, p. 54), organizations that have innovative cultures are flexible, adaptable, and experiment with ideas. These organizations are characterized by flat hierarchy and titles and other status distinctions tend to be downplayed. Khan, Usoro, Majewski and Kuofte (2010) explain innovation as the introduction and implementation of new ideas that positively benefit the organization and its members. Managers regard innovation as the major source of competitive advantage (Khan et al., 2010). Thus, it can be argued that the moderate mean score for innovation and risk taking arises from the nature of any institution of higher learning’s hierarchy.

4.2. Job satisfaction

The study’s second hypothesis was that academic professionals were not satisfied with their jobs. The results indicate that the institution’s academic professionals were satisfied with their co-worker relation, supervision support, work performed, and the advancement opportunities they received. They were, however, not satisfied with the salary they were receiving.

Co-worker relations had the highest mean score response of 3.79. In this regard, academic professionals were more satisfied with their co-worker relations. These results are consistent with those from Boeve’s (2007) study on the job satisfaction factors for a physician assistant (PA) faculty in Michigan, where the respondents were most satisfied with co-worker relations. However, Alam and Mohammad (2011) found a moderate mean score for JDI dimension co-worker relation on their study of the level of job satisfaction and intent to leave among Malaysian nurses.

The results of the study also indicate that supervision support had a high mean score of 3.65. This indicates that academic professionals were satisfied with the supervision support received in their respective units. The results confirm findings from studies such as buddy's (2005) which found that employees at a public health institution in the Western Cape, South Africa, were satisfied with the received supervision, and Sowmya and Panchanatham’s (2011) finding of a high mean score for supervision support in the Indian banking sector as measured by JDI. On the contrary, Alam and Mohammad’s (2011) study on Malaysian nurses found a moderate satisfaction with supervision support. Nonetheless, the high mean score of supervision support obtained in the present study could be a function of institutional leadership styles.

The salary subscale had the least mean score of 2.76. This score shows that academic professionals were not satisfied with the salary they received during the time of the study. Gurbuz (2007) argues that although employees want to be paid fairly for their work, money is not an effective way to motivate individuals. Hays and Hills (1999) concur with Gurbuz (2007) that if managers will lose the motivation battle should they reward performance only with money, as there are other motivators such as freedom and organizational flexibility. Amar (2004) argues that money has been the most important outcome from employment and the only outcome that employers offered to their employees. Maslow (1954) notes that money is important as it serves the function of meeting physiological needs - food, water, shelter and clothing, hence, people would want to have their physiological needs fulfilled before other needs are satisfied. The inconsistencies surrounding the nature of this relationship from several authors can be used to support the finding in this study. If the institution in the present study only uses money as a source of motivation, then this could explain the lack of satisfaction with extrinsic motivators. However, employees’ low level of the satisfaction on the salary subscale would not be surprising if the institution is failing to pay its employees adequately.

Intrinsic job factors in the present study had a high mean score. Wood, Wallace, Zeffene, Fromholtz and Morrison (2001) explain that intrinsic job satisfaction as related to what people do in their jobs, such as the work itself, recognition and job autonomy. In this regard, work had a high mean response of 3.60 which means that academic professionals were satisfied with their jobs. These results are consistent with a number of studies, such as buddy’s (2005) findings that the employees at a public health institution in the Western Cape Province in South Africa, were satisfied with the nature of their work.

Advancement opportunities had a moderate mean score of 3.44. This shows that respondents at the institution were moderately satisfied with the advancement opportunities offered. These results are consistent with those from Aydin’s (2012) study of the effect of motivation factors and hygiene factors on research performance of Foundation University members in Turkey, where the respondents reported a high mean score for advancement opportunities received at the Foundation University. Similarly, Castillo and Cano (2004) found a high mean score for advancement opportunities in their study on factors explaining job satisfaction among faculty members in Mexico. However, Malik, Nawab, Naeem and Damish’s (2010) study on job satisfaction and organizational commitment found a moderate mean score for job satisfaction among Pakistan’s public sector university teachers. It can, therefore, be argued that employees are more satisfied with their jobs if they see a path available to move up the ranks in the company, given more responsibility and a higher compensation.

4.3. Organizational culture and job satisfaction

The positive significant relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction indices noted in the present study concur with findings from other similar studies. For example, bund’s (2003) survey of marketing professionals in a cross-section of American firms to assess the impact of organizational culture on job satisfaction noted that job satisfaction levels varied across organizational culture typologies. McKinnon, Harrison, Chow and Wu’s (2003) study focusing on participants from a diverse Taiwanese manufacturing companies also shows that organizational cultural values of respect for people; innovation, stability and aggressiveness are strongly associated with affective commitment, job satisfaction and information sharing. Furthermore, other organizational cultural factors play a significant role in the establishment of job satisfaction. Bashayreh’s (2009, p. 2) study on the relationship between organizational culture and employee job satisfaction among academic staff at Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM), shows the significance of the relationship between factors such as organizational supportiveness, innovation and stability, and communication and job satisfaction. Thus, various organizational cultural values lead to organizational commitment, job empowerment and job satisfaction.

CONCLUSION

The study of perceptions of academics from the studied South African university of technology regarding organizational culture and job satisfaction deduced, from the data analysis that, academic employees had positive views on the culture evident at the existing institution. The academics were gently satisfied with their jobs and there was a moderate relationship between organizational culture and job satisfaction. Hence, the creation of an organizational culture that leads to employee satisfaction is important towards the establishment of academic employees’ adjustment to a newly established vocationally-oriented institution of higher learning in a developing context.

Recommendations for practice

The study recommends that management ensures that every employee understands and identifies with the culture of the institution, as organizational culture relates to employee behavior. It recommends further that job satisfaction levels be monitored periodically as this assists towards the achievement of the academics’ job satisfaction. Finally, it is recommended, drawing on the fact that the institution must celebrate and can communicate both all positives and dissatisfactions to the stakeholders that, committees should be formed to develop action plans that will enhance satisfaction and resolve identified problem.

Contribution of the study and future research

The study contributes to the generation of knowledge about organizational culture and job satisfaction of academic professionals at institutions of high learning, forms a base for similar studies and recommends strategies that can be adopted in other UoTs in South Africa towards the development of organizational cultures that promote job satisfaction. Finally, a corroborative study, looking at the two concepts from a phenomenological point of view could be adopted in future, just as future studies on job satisfaction and organizational culture can use other variables to get a complex picture.

REFERENCES

- Alam, M. M., & Mohammad, J. F. (2009). Level of job satisfaction and intent to leave among Malaysian nurses. Business Intelligence Journal, 3(1), 123-137.

- Amar, A. D. (2004). Motivating knowledge workers to innovate a model integrating motivation Dynamics and antecedents. European Journal of Innovation Management, 7(2), 89-101.

- Aydin, О. T. (2012). The impact of motivation and hygiene factors on research performance: An empirical study from a Turkish University. International Review of Management and Marketing, 2(2), 106-111.

- Sartell, M. (2003). Internationalisation of universities: a university culturebased framework. Higher Education, 45(1), 43-70.

- Bashayreh, A. M .K. (2009). Organisational culture and job satisfaction: A case study of academic staff at Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM). [Electronic version]. Unpublished thesis for Masters of Human Resources Management, Malaysia: Universiti Utara.

- Bauer, T., & Erdogan, B. (2014). Handbook on Organizational Behavior. USA: Flat World Education, Inc.

- Beam, R. A. (2006). Organisational goals and priorities and the job satisfaction of U.S. journalists. J&C Quarterly, 83(1), 169-185.

- Bikmoradi, A., Brommeis, M., Shoghli, A., Zavareh, D. K., & Masiello I. (2008). Organizational culture, values, and routines in Iranian medical schools. Springer Science & Business Media B.V, 57, 417-427.

- Boeve, W. D. (2007). A national study of job satisfaction factors among faculty in physician assistant education, Masters Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. Retrieved from http://commons. emich.edu/ theses/60

- Brough, R, & Frame, R. (2004). Predicting police job satisfaction and turnover intentions: The role of social support and police organizational variables. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 33(1), 8-16.

- Burchell, N., & Kolb, D. (2007). Stability and change for sustainability. Business Review, 8(2), 33-41.

- Castiglia, B. (2006). The impact of changing culture in higher education on the personorganisation. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 10(2), 23-43.

- Castillo, J. X., & Cano, J. C. (2004). Factors explaining job satisfaction among faculty. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(3), 65-74.

- Chiboiwa, M. W., Chipunza,

- , & Samuel, M. O. (2011). Evaluation of job satisfaction and organisational citizenship behaviour: case study of selected organisations in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Business Management, 5(7), 2910-2918.

- Chipunza, C., & Gwarinda, S. A. (2010). Transformation leadership in merging higher education institutions: a case study. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(1), 110.

- Choi, Y. S., Martin, J. J. & Park, M. (2008). Organizational culture and job satisfaction in Korean professional baseball organizations. International Journal of Applied Sports Science, 20(2), 59-77.

- Chow, C. W., Harrison, G. L., McKinnon, J. L., & Wu, A. (2001). Organisational culture: association with affective commitment, job satisfaction, propensity to remain and information sharingin a Chinese cultural context’. Centre for International Business Education and Research (CIBER). Working paper, Faculty of Business & Economics, San Diego State University.

- Cranny, C. J., Smith, P. C., & Stone, E. F. (1992). Job satisfaction: How people feel about their jobs and how it affects their performance. Lexington Books: New York.

- Dastmalchian, A., Javidon, M., & Alam, K. (2001). Effective leadership and culture in Iran: An empirical study. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(4), 534-558.

- Delobbe, N., Haccoun, R. R., & Vandenberghe, C. (2001). Measuring core dimensions of organisational culture: a review of research and development of a new instrument, unpublished manuscript, Universite catiiolique de Louvain, Belgium.

- Deutschman, A. (2004). The fabric of creativity. Fast Company, 89, 54-62.

- Dian-Yan, L., Chia-Ching, T., Shu- Hsuan, C. (2014). Mediating Effect between Supportive. Culture and Job Satisfaction in Administrative Services at Higher, 24(6), 627-640.

- Ellen Hazelkorn, E. (2012). Three key challenges facing higher education and policymakers. Retrieved from http://www.oclc.org/publications/nextspace/artides/issuel9/three-key-challenges.en.html

- Fey, C., & Denison, D. R. (2003). Organizational culture and effectiveness: Can an American theory be applied in Russia? Organization Science, 14(6), 686-706.

- Gary, P. (2012). Creating an excellence oriented post-merged organisational culture through a structured approach to employee engagement - a study of selected merged institutions of higher learning in South Africa. Africa Insight, 42(2), 136-156.

- Gazzola, P., Jha-thakur, U, Skidd, S. , Peel, D., & Fischer, T. (2011). Enhancing Environmental Appraisal Effectiveness: Towards an Understanding of Internal Context Conditions in Organisational Learning. Planning Theory & Practice, 12(2), 183-204.

- Gifford, B. D., Zammuto, R. E, & Godman, E. A. (2002). The relationship between hospital unit culture and nurses’ quality of work-life. Journal of Health Care Management, 47(1), 13-26.

- Gray, J. H., Densten, I. L., & Sarros, J. C. (2003). A matter of size: does organisational culture predict job satisfaction in small organisations? Working paper 65/03. Faculty of Business & Economics, Monash University.

- Gready, P. (2013). Organisational Theories of Change in the Era of Organisational Cosmopolitanism: lessons from Action Aid’s human rights-based approach. Third World Quarterly, 34(8), 1339-1360.

- Greenberg, J., & Scott, K. S. (1996). Why do employees bite the hands that feed them? Employee theft as a social exchange process. Research in Organisational Behaviour, 18, 111-166.

- Greene, J., Reinhardt, A., & Lowry, T. (2004). Teaching Microsoft to make nice? Business Week.

- Griffin, M. A., Patterson, M. G., & West, M. A. (2001). Job satisfaction and teamwork: the role of supervisor support. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 22(5), 537-550.

- Gurbuz, A. (2007). An assessment on the effect of education level on the job satisfaction from tourism sector point of view. Dogus Universitesi Dergisi, 8(1), 36-46.

- Hays, M. J., & Hill, V. A. (1999). Gaining competitive service value through performance motivation. Journal of strategic performance measurement, (Oct. /Nov.), 36-40.

- Herzberg E, Mausner, B., & Snyderman, В. B. (1959). The motivation to work. New York: Wiley. Higher Education, 45(1), 43-70.

- Hill, M. D. (2014). A Theoretical Analysis of Faculty Job Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction. Educational Research Quarterly, 10, 3-6.

- Khan, I. U., Usoro, A., Majewski, G., & Kuofie, M. (2010). The organizational culture model for comparative studies: A conceptual view International Journal of Global Business, 3(1), 53-82.

- Kono, T. (1990). Corporate Culture and Long-range Planning, Long Range Planning, 23(4), 9-19.

- Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Bell, B. S. (2003). Workgroups and teams in organizations. In W. C. Borman,

- Ilgen & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 12 (pp. 333-375). New York: Wiley- Blackwell.

- Kulkarni, A. (2010). Primary characteristics of organizational culture. Retrieved from http:// buzzle.com/articles/primary- characteristics-of-organizational- culture.html

- Kumar, R. (2005). Research Methodology. London: Sage Publications.

- Lee, Y, & Chang, H. (2008). Relations between team work and innovation in organizations and the job satisfaction of employees: A factor analytic study. International Journal of Management, 25(4), 732-739, 779.

- Leibowitz, B. (2014). Conducive Environments for the Promotion of Quality Teaching in Higher Education in South Africa. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning 2(1), 49-73. https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v2il.27

- Lok, P., & Crawford, J. (2004). The effect of organisational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and organisational commitment. The Journal of Management Development, 23(4), 321-338.

- Luddy, N. (2005). Job satisfaction amongst employees at a public health institution in the Western Cape. Unpublished theses for Master in Economic and Management Science, Western Cape:University of Western Cape.

- Lund, D. B. (2003). Organisational culture and Job satisfaction. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 18(3), 219-236.

- Mabasa, Fu D., & Ngirande, H. (2015). Perceived organisational support influences on job satisfaction and organisational commitment among junior academic staff members. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 25(4), 364-366.

- MacDonald, S., & MacIntyre, P. (1997). The generic job satisfaction scale: scale development and its correlates. Employee assistance Quarterly, 13(2), 1-16.

- Macintosh, E. W, & Doherty, (2010). The influence of organisational culture on job satisfaction and intention to leave. Sports Management Review, 13, 106-117.

- Malik, M. E., Nawab, S., Naeem, & Danish, R. Q. (2010). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment of university teachers in public sector of Pakistan. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(6), 17-26.

- Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper.

- Mathew, J. (2007). The relationship of organisational culture with productivity and quality: A study of Indian software organisations. Employee Relations, 29(6), 677-695.

- McKinnon, J., Harrison, G., & Wu, A. (2003). Association with commitment, job satisfaction, propensity to remain, and information sharing in Taiwan. International Journal of Business Studies, 11(1), 25-44.

- Mohelska, H., & Sokolova, M. (2014). Organisational Culture and Leadership. - Joint Vessels? 5th ICEEPSY International Conference on Education & Educational Psychology, 171, 1011-1016.

- Mohelska, H., Pitra, Z. (2012). Manaherskü metody. (Isted.) Praha: Professional Publishing.

- Moorman, R. H. (1993). The influence of cognitive and affective based job satisfaction measures on the relationship between satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviour. Human Relations, 46, 756-776.

- Moses, I. (1986). Promotion of Academic Staff. Higher Education, 15, 33-37.

- Naicker, N. (2008). Organisational culture and employee commitment: a case study. Unpublished thesis for Masters of Business Administration, Durban: Durban University.

- O’Malley, A. (2014). Theory and Example of Embedding Organisational Change: Rolling Out Overall Equipment Effectiveness in a Large Mining Company. Australian Journal of Multi-disciplinary Engineering, 11(1).

- O’Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to personorganization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487-516.

- Organisational citizenship behaviour: case study of selected organisations in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Business Management, 5(7), 2910-2918.

- Stephen T., Robbins, Timothy A., Judge, Elham S., Hasham. (2001). Organizational Behavior, England. Pearson.

- Pearson, D. A., & Seiler, R. E. (1983). Environmental Satisfiers in Academe. Higher Education, 12,

- Robbins, S. P. (2001). Organisational Behavior. New Jersey: Prentice - Hall, Inc.

- Robbins, S. P., Judge, T. A., Odendaal, A., & Roodt, G. (2013). Organisational Behavior. Prentice - Hall, Inc: South Africa.

- Rue, L. W. & Holland, P. G. (1986). Strategie Management. McGraw- Hill, Inc., New York.

- Saari, L. M., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Wiley Inter Science, 43(4), 395-407.

- Sabri, P. S. U., Ilyas, M. & Amjad, Z. (2011). Organizational culture and its impact on the job satisfaction of the University teachers of Lahore. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(24), 121-128.

- Salman, H., Saira, S., Amjad, H., Sana, Y„ & Muhammad, I. (2014). The impact of organisational culture on job satisfaction, employees’ commitment and turnover in intention. Advances in Economics and Business, 2(6), 215-222.

- Sempane, M. E., Rieger, H. S., & Roodt, G. (2002). Job satisfaction in relation to organisational culture. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 28(2), 23-30.

- Silvester, J., & Anderson, N. R. (1999) Organisational Culture Change: An Intergroup Attributional Analysis. Journal of Occupational & Organisational Psychology, 72(1), 1-24.

- Smith, P. C., Kendall, L. M., & Hulin, C. L. (1969). The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Chicago: Rand McNally.

- Sonja, T., Matjah, M., Monty, L. (2008). The impact of culture on organizational behaviour.). Management, 13(2), 27-39.

- Sowmya, K. R., & Panchanatham, N. (2011). Factors influencing job satisfaction of banking sector employees in Chennai, India. Journal of Law and Conflict Resolution, 3(5), 76-79.

- Timmins, P., Eham, M, McFadyen J., & Ward, J. (2006). Educational Psychology in Practice, 22(4), 305-319.

- Trivelas, P., & Dargenidou, D. (2009). Organisational culture, job satisfaction and higher education service quality: The case of Technological Educational Institute of Larissa. The TQM Journal, 21(4), 382-399.

- Trivella, P., & Dargenidou, D. (2009). Organisational culture, job satisfaction and higher education service quality: The case of Technological Educational Institute of Larissa, The TQM Journal 21(4), 382-399.

- Tsai, Y. (2011). Relationship between organizational culture, leadership behaviour and job satisfaction. BMC Health Services Research, 11,

- Van Knippenberg, D., & Sleebos, (2006). Organizational identification versus organizational commitment: self-definition, social exchange and job attitudes. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 27(5), 571-584.

- Vukomjanski, J., & Nikolic, M. (2013). Organisational culture and job satisfaction: The effects of company’s ownership structure. Journal of Engineering Management and Competitiveness, 3(2), 41-49.

- Weiss, D. J., Dawis, R. V, England, G. W, & Lofquist, L. H. (1967). Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire, 22, Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Industrial Relations Center.

- Wood, J. M., Wallace, J., Zeffane, R. M., Fromholtz, M., & Morrison, V. (2001). Organisational Behaviour: Global Perspective,

- Zafirovski, M (2005). Social exchange theory under scrutiny: A positive critique of its economic- behaviourist formulation. Electronic Journal of Sociology, 1-40.