Security in the worldview of Russians

Published: March 10, 2014

Latest article update: Dec. 20, 2022

Abstract

This article deals with the role of security in shaping an individual’s standpoints, opinions, attitudes, and unique world picture. It is argued that security/insecurity is a subjective notion of individuals about the absence/presence of threats to their existence. The results of a study of the security notions maintained by Russians are described. The data obtained give grounds to suggest that the following characteristics exist in the ordinary consciousness of Russians: security is perceived as a state associated with inactivity; security is seen as the basis of harmonious interpersonal relations; security is considered a kind of “ideal world” and is understood as powerful. A typology of Russians based on the specifics of these security notions is presented.

Keywords

Security, security factors, ordinary consciousness, world picture, typology

Introduction

In the Russian language the word security is formed by simply adding a prefix (bez, without) to opasnost’ (danger), which thus turns danger into an ideal state of reliability, safekeeping, and the absence of insecurity. However, this interpretation of the word security restricts the meaning of the concept. In English security and danger are derived from different stems and have different semantics. In this light it seems important not to reduce an understanding of security to protection against dangers exclusively but instead to deepen and widen the conceptual semantics of security.

Rothschild (1995) notes that over the last few centuries the concept of security has been interpreted in different ways and has been evolving, together with the transformation of Western society, from weakly perceived notions in which it acts as an inner sensation of a person to increased rationalism and definiteness. In the course of this evolution the concept of security has been verbalized, fixed, and used to denote a right of an individual and the condition of one’s individual freedom as set forth in legal regulations adopted in the days of bourgeois revolutions in Western Europe and the United States.

A constant state of flux can be seen in modern society: the rapid tempo of reforms, the development of means of mass communication, changes in social structures and people’s relationships. “Sociopsychological parameters of social interaction depend largely on the type of culture as well as on certain strategies of behavior associated with national, mental features” (Dontsov & Perelygina, 2011b, p. 232).

Radical changes in the world destroy an individual’s orientation toward social reality. People find themselves lost in a vortex of events, feel pressured by the surrounding world, and are unsure of their future and the safety of their lives. They face a discrepancy between old and new views, values, and traditions. Motivational factors and basic needs also change regularly. Kozyrev (2008, p. 34) states, “The traditional Russian method of negative mobilization, actualizing the image of the «enemy», is nearly the only way of consolidating society in the face of external threats and internal disorganization”.

“Security is a condition of a person according to which he/she can satisfy basic needs for self-preservation and [can have a] perception of being secure (psychologically) in society” (Dontsov, Zinchenko, & Zotova, 2013, p. 99).Security creates conditions for knowledge, exchange, and interaction within one’s sociopsychological space. A condition of danger enhances preservation and one’s detachment from one’s sociopsychological space; in these circumstances a protective function is manifested. Alack of security conditions leads to a defensive stance and generates resistance that can be outward or inward: outward when conventional norms are broken, when so-called discipline infringement and acts of “civil disobedience” take place; inward when there is a flight from social contacts, self-accusation, negative self-attitude, and auto-aggression. Such resistance complicates the system of interpersonal relations and devastates every participant in this process. A long period of emotional tension provokes a search for destructive ways out of a mentally traumatic situation. “It is the deprivation element that determines social behavior by its integral influence” (Dontsov & Zotova, 2013, p. 81).

The security/insecurity of reality facilitates the formation by every person of a specific set of beliefs, opinions, and attitudes — a unique picture of the world. Guided by personal views on security people live and envisage events, build up behavior patterns, evaluate the results of their actions, and modify their interpretations of the world. A constant need to act in a condition of uncertainty, including those in which there is a lack of time for decision making and a lack of information, results in risk becoming an essential signifying element in every person’s life.

Analysis of modern views on security shows that the problem of the essence of security and, correspondingly, of its definition still remains unresolved; an understanding of security that reveals the essence of the phenomenon is still being worked out.

The theoretical and methodological foundations of security were properly addressed by the scientific community in the last decade of the 20thcentury. The following lines of security research are of particular interest:

- The theory and practice of risk management as a basis for the provision of security (T.A. Balabanov, P.G. Grabovoy, I.S. Komin, A.A. Kudryavtsev)

- Social studies of security (U. Beck, E. Giddens, N. Luhmann, V.N. Kuznetsov, P. Sztompka, and others)

- Philosophical and methodological works that consider the problem of security asa whole (G.V. Bro, M.U. Zakharov, N.M. Pozhitnoy, V.S. Polikarpov, A.I. Subetto, and others)

- Security in the context of co-evolutionary and sustainable development (E.I. Glushenkova, V.I. Danilov-Danil’yan, S.I. Doroguntsov, A.V. Ij’ichev, V.V. Mantatov, L.V. Mantatova, N.N. Moiseev, U.V. Oleynikov, A.N. Pal’chuk, A.L. Romanovich, A.D. Ursul, and others).

Thus, scholars and practitioners in Russia have contributed greatly to the investigations of different aspects of security. However, some issues require further exploration in social psychology — namely, notions of security.

In the ordinary consciousness of the people of each nation views on security exist that are typical of their particular culture, history of development, and ethnically colored value system.

The Russian intellectual tradition paid strikingly little attention to security issues in spite of the state’s permanently being at war and experiencing several peasant rebellions and local riots. Security in Russia used to be a focus of the state, policymaking, and diplomacy.

Social and economic reforms of the late 1980s and the early 1990s substantially shifted the official “coordinate system” of social space. Today the majority of people have to alter their behavioral, practical, everyday views of the world. Some do it in order to survive; others, to enlarge their opportunities. With the change of perceptions, behavioral strategies providing group affiliation and support also are modified (Klimova, 2002). In addition, stereotypes and attitudes, myths and prejudices add to Russians’ chronic lack of security. In the popular mind a sense of danger is growing together with mutual hostility.

Modern times pose new challenges for a person as a member of society. The period during which a new world outlook is being shaped, old stereotypes are being destroyed, and old traditions are being replaced by new ones stirs interest in security issues and notions. New challenges and requirements generated by the modern conditions of human existence, along with emerging types of risk, cannot help influencing the nature of one’s perception and view of oneself (Soboleva, 2001). Dontsov and Perelygina (2011a) emphasize that the “security of communications depends mainly both on the level of coordination of the actions of participants in an interaction and on the degree of dedication and social support that encourage the psychological resistance of actors in a social interaction” (p. 30).

In the system of humanitarian thought this interest in security issues and notions has been a lasting one. Scientists have been trying to broaden their ideas of the essence of this phenomenon. However, there are still “blind spots,” and the problem of Russian views regarding security is one of them.

The theoretical corpus of knowledge collected over the history of civilization testifies to the fact that security is an extremely broad phenomenon. So far three basic aspects of the study of security have been marked out. One approach treats security as multidimensional; the second considers security as a multifaceted representation of the optimal condition and the actual condition of security; the third one considers security as an objective. The condition of security can be of a lesser or a greater extent, or it may not exist at all. The objective can be precisely realized or vague, half-conscious. The security idea can be either true — for instance, when it reflects the security condition in the right way — or distorted — for example, when it underestimates or exaggerates the real degree of danger or safety. In any case the idea takes a dominating position with regard to conditions and goals because one cannot estimate conditions without the notion, and any goal is set according to the estimates obtained.

It has been intrinsic to human beings to value a feeling of security. The world around us was and is still hostile: pitfalls beset us everywhere. That is why danger in ordinary consciousness has been shaped as a complex concept, as a certain composite image, as a mandatory element, as every person’s world picture.

A developing world picture of a subject is commonly seen as a dynamic set of individually significant content areas (K. Jaspers), which one possesses at a certain time and which define the internal logic of the construction of one’s behavior and life, one’s life creation (S.V. Lur’ie, R. Redfield, and others). It is an integrated, multilevel system of human notions of the world, of other people, of oneself and one’s activities, a system that “mediates and interprets through itself any external impact” (Smirnov, 1985, p. 142). Content structures of this phenomenal psychic construct can be adequately expressed by the words picture or image (A.N. Leontiev), as they emphasize its key aspects: diversity integrated into its components, constancy and subjective marking of these components, structural wholeness, and dynamics “as a potential possibility embedded in [its] composition” (Aksyonova, 2000, p. 3).

Aksyonova argues that the subjective world picture (individual or universal) that a person has is a specific “way to describe the world” (Aksyonova, 2000, p. 5).Although, according to Hirsh (1988), approximately 80% of background information has a universal character, it is centered on the subject’s “self,” and its basis traditionally consists of an individual history in the context of which all other events and acquired ideas are collected and interpreted. Choosing or creating this image one manifests oneself by structuring, noticing, identifying, placing, defining, or confirming certain concepts of the world order in one’s mind. For this reason, individual self-expression, subjective partiality, the buildup of oneself, the creation of human life cannot be separated from a way of describing the world. The different subsystems constituting a world picture participate in intricate dynamic relations of mutual conditioning: they are being folded, symbolized, shifted from the focus of consciousness to the periphery; they form temporary situation-charged models, frames, and so forth. Any world picture represents an ensemble of mutually interrelated, multimodel notions of the world and of the self. This world picture is maintained by the subject; it is confusing for an observer but is internally logical.

Therefore, one’s emotional state, attitude, and perception of the world are altered depending on the absence or presence of security at any given moment. The wider and more multifaceted one’s world picture is, the more necessary it is to design orientation tools; for this reason at every new turn of the picture’s enlargement a form of its representation (a special interface) already accumulated in its materials is especially crucial. Because of age, individual peculiarities, upbringing, education, line of work, abilities, and so on, the picture of “a secure world” can combine predominantly sensitive-spatial, spiritual-cultural, metaphysical, philosophical, ethical, physical, and other elements and can be introduced to each owner with a different degree of integrity. Consequently, the study into personal security should include all the above-mentioned factors.

The range of problems involving social and subject notions constitutes a relatively developed field of psychology. The data documented by a number of researchers characterize sets of different notions: moral (Y. H. Anishcenkova, V. I. Rublik), pertaining to world outlook (G.N. Malyuchenko, V.M. Smirnov), temporal and spatial (S.Y.Pankova), affected by gender roles (T.N. Arkantseva, O.B. Otvechalina), and professional (E.L. Kasyanik, I.V. Makarovskaya, G.S. Pomaz, E.A. Semyonova). Scientists’ interests also involve notions of success (Y.V.Artamoshina), subjective well-being and happiness (H.V.Vinichuk, S.V.Zhubarkin), freedom (V.I.Atagunov), AIDS and cancer (I.B.Bovina, E.V.Vlasova), festive events (S.V.Tichomirova), and communicative qualities (S.S Kostyrya). Similar studies have identified peculiarities of projections of the objective world in an individual’s consciousness, which define to a great degree a subject’s value priorities and life orientations.

It is intrinsic to human beings to feel secure or insecure as a response to alarming signals and sense perceptions, instinctive reactions of organism, and intuition; in other words, a sense of security (insecurity) involves the subjective views of individuals about whether there are any or no threats to their existence. These views help one to modify behavior patterns and to avoid danger. “The ‘social taboo’ situation as well as the situation of a subject’s encounter with a natural object perceived as potentially threatening can cause intensification of a pre-existing itch for action or provoke forbidden actions” (Zinchenko & Zotova, 2013, p. 111).

The restriction of possibilities for personal self-realization that arises from an absence of security conditions leads to specific personality changes that encourage one to work out a set of attitudes toward the surrounding world and one’s place in it based on one’s experiencing a break of meaningful ties and relationships and a feeling that one lacks protection.

Moreover, some researchers are convinced that inaccurate security notions could have a worldwide disastrous outcome. A Japanese expert, K. Mushakoji, in particular, arrived at the conclusion that “the core of a worldwide extreme situation that would make life in its present form highly problematic lies in the crisis of our idea of security and its definition” (Mushakoji, 1991, p. 5).

A subjective interpretation of this phenomenon is largely the result of a person’s attitude to it, and to a high degree it determines corresponding behavior (D.A. Leontiev, H.C. Pryazhnikov, V.I.Pyslar’, N.V.Rodionova, A.N.Slavskaya, G.C.Dickson, К.Р.Krishna, К.Schneider, N.Posse, N.D.Weinstein). This interpretation is not only the guideline for evaluating one’s own behavior, but, most important, it defines “standards” for such an assessment. In terms of reflexive status personal security is not so much a factual position of individuals as it is a reflection of their subjective views on security. An individual’s state of being secure is more likely to be determined by subjective psychological criteria than by an objective, factual position.

A highly productive method for exploring security is to study a person’s worldview in the framework of the psychosemantic approach (V.F. Petrenko, A.G. Shmelyov, and others).In psychosemantics a paradigm of constructivism is realized in which the world picture is interpreted not as a mirror reflection of reality but as one of the possibly “biased” cultural and historic models of the world created by a single or a collective subject. “In this sense psychosemantics upholds the position that implies the diversity of world models, the idea of the pluralism of truth, and, as a result, the idea of multiple lines of development of an individual, a community, a country, the whole of humankind” (Petrenko, 2010, p. 9). In the context of the psychosemantic approach, personality is defined as a holder of a unique world picture, as a “microcosm of individual meanings and connotations” (Petrenko, 2010, p. 9).Psychosemantic methods were further elaborated in the works of V.V. Stolin, M. Calvinjo on self-awareness, V.K. Manerov on the psychodiagnostics of personal speech, and L.A. Korostylyova on subjective life experience in the context of an individual’s self-realization.

Methodology

The aim of the research was to study the security notions of residents of Russia. The research consisted of two tasks:

- To analyze associations connected to the concept of security

- To create a typology of the behavior of Russians in regard to their perception and evaluation of security

The researchers used two methods:

- A survey identifying at least three associative links to the word security

- The “semantic differential” method with the D. Peabody / A.G. Shmelyov modification

Processing of the results was done through correlation (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient) and factor analysis via the “SPSS11.0” package. The processing also included group-data matrix formation by the summation of individual protocols. Factor analysis was carried out with the use of principal components and varimax rotation. To single out types of respondents, cluster analysis (Ward’s Distance Metric: Squared Euclidean) was applied.

The sample (650 respondents) was balanced according to gender and education level (48% males and 52% females, 53% with a diploma of higher education and 47% with a secondary level of education).

Analysis of the results

Notions of security

The most frequent associations with the word security were as follows:

“stability” (25.3% of the respondents) | “comfort” (14.4%) |

“calmness” (20.2%) | “pleasure” (13.7%) |

“defensibleness” (18.1%) | “trust” (12.3%) |

“harmony” (17.3%) | “confidence” (10.1%) |

“threat” (16.6%) | “friendliness” (9.4%) |

A supplementary examination of the associations formulated by the respondents gave the opportunity to identify groups of notions linked with security. The following associations are the key ones:

- Emotional states that can be designated as Inactivity and Passivity (stability, passivity, calmness, defensibleness, vivacity, inspiration, light-heartedness, relaxation, confidence, laziness) — 40% of all associations

- Openness as an attitude toward people (trust, harmony, friendliness, care, openness) — 16% of all associations

- Ideal World, which includes both values (beauty, peace, freedom, happiness, health) — 11% of all associations, and needs (self–preservation, protection, sex, reliability, food, warmth) — 12% of all associations

- Outward Defensibleness (safeguarding, FSS (Federal Security Service), contraception, protection, dogs, police, army, Ministry for Emergencies, armed forces, body armor) — 8%

- Threat (threat, hurricane, fear, risk) — 5%

These results allow us to suppose that in Russians’ everyday consciousness there exist the following views on security.

- Security is a condition linked to inactivity.

- Security is the basis for harmonious interpersonal relations of trust and friendliness.

- Security is a kind of “ideal world” with the nonstop satisfaction of needs and the realization of dominating values.

- Security is power that can protect one in case of danger.

Table 1. Results of the factor analysis of Russians’ security notions

Factor number | % of total variance | Factor content | Name |

1 | 20.8 | Openness .89, hilarity .88, friendliness .92 | Openness |

2 | 11.5 | Pleasure 0.90, laziness .86, inspiration .75 | Inactivity/ |

3 | 9.01 | Hurricane .72, modesty .58, contraception .42 | Protection |

4 | 8.76 | Protection .65, nonchalance .59, untouchability .58 | Nonaggression |

5 | 7.49 | Calmness .77, joy .62, balance .44 | “Security is harmony” |

6 | 5.15 | Peace .77, relaxation .61, friendliness .44 | “Security is calmness” |

7 | 5.0 | Threat .90, dog .65 | “Security is safeguarding” |

8 | 4.84 | Beauty .83, no thoughts of tomorrow .53 | “Security is pleasure” |

9 | 3.24 | Trust .91 | “Security is faith” |

10 | 3.18 | Self-preservation .72, friendliness .58. | “Security is communion” |

11 | 2.52 | Comfort .87, freedom .50 | “Security is democracy” |

12 | 2.16 | Harmony .97 | “Security is balance” |

13 | 2.05 | Stability .93 | “Security is constancy” |

14 | 2.32 | Defensibleness .96 | “Security is legitimacy” |

The average-value analysis of Russians’ security notions based on score average was later extended by factor analysis because it was also necessary to define not only dominant hierarchical ties between the associations presented and their distribution according to their level of significance (vertical slice) but also semantic, content-related ties classifying the associations collected into separate blocks and factors.

The factoring out of associations allowed us to denote the inner differentiation and semantic structure of the notion of security in the respondents’ consciousness.

Factor-analytic processing resulted in singling out 14factors constituting 63% of the total variance (Table 1). This number of factors testifies to the fact that this notion is cognitively complex and has semantic indeterminacy for the respondents.

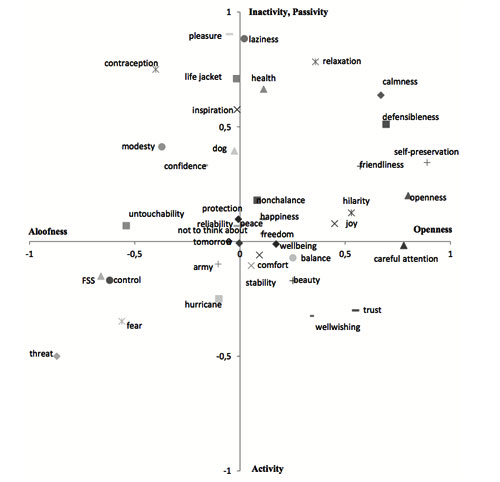

The semantic field of the respondents’ views on security is formed by combining the two leading factors: Openness, Inactivity/Passivity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Semantic field of Russians’ notions of security

Analysis of the semantic field shows that “relaxation” is situated in the same semantic zone as “nonchalance,” “joy,” “happiness,” “hilarity,” “self-preservation,” “freedom,” and “friendliness.” The union of the leading factors creates a “safe-world” zone, a community where the respondents feel secure and protected, not expecting any harm from the people around. As a result they experience positive emotions and find themselves carefree and relaxed.

It should be stressed that there are no state enforcement services — police, the FSS, army, etc. — in the security zone, which speaks to the fact that mass consciousness is forced to consider safety an individual’s challenge, which well-off people, for instance, can resolve by hiring bodyguards. However, among all the associations to the word security one cannot find words denoting some actions. There is no “work” or “service”; even the most frequent association is not “protection,” which supposes taking some measures for providing personal security, but “defensibleness,” a state provided by others.

Conversely, a “danger” zone formed by negative factors consists of such associations as “control,” “FSS,” “army,” “hurricane,” “fear,” “threat.” Ordinary consciousness does not see professional security agents as protectors but as a threat and reason for fear. “Current authorities remain a source of threat to citizens not in a political sense but in an economic one. If earlier they used to unite roles of an unprecedented liar and a trustee, now they have freed themselves from such duality: custodian care has become symbolic whereas untrustworthiness of promises and liabilities has considerably grown. . . . In response to it the concept “security” starts altering again most visibly when it concerns private life. It is increasingly limited to notorious ‘personal immunity’ — this time people need protection rather from the underworld than from the state” (Panarin, 1998, p. 14).

A typology of russians based on their security notions

The aim of our study of security notions was to assess the possibility of dividing the respondents into groups according to the correlation of estimates of the concepts under study. Six months later a second study was conducted in order to check the stability of the results. It showed that the characteristics found applied to a number of stable personality parameters (intergroup movement of the respondents constituted 10%).

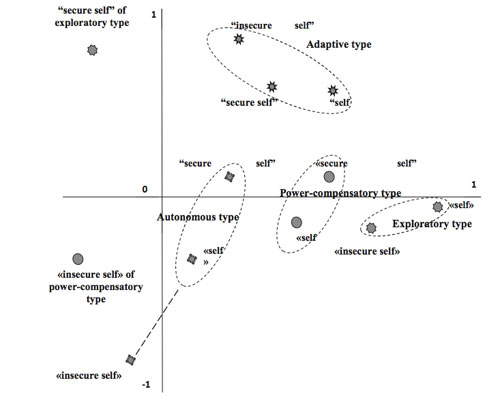

The first group is represented by those respondents with a high degree of similarity in assessing the images “secure self” and “self” (r=0.72, where р<0.01) with the opposite estimate of the image “insecure self.” The second group is characterized by the same high degree of similarity while evaluating all three images; that is, it demonstrates poor differentiation of features belonging to the images “secure self,” “insecure self,” and “self ” (r=0.912 and r=0.79, where р<0.01). The third group shows similar estimates of the images “secure self ” and “self ” (r=0.515,where р<0.01) according to some scales, while their assessments of the images “insecure self ” and “self ” are less similar (r=0.363, where р<0.05). The fourth group is distinguished by a high degree of similarity between the images “insecure self ” and “self ” (r=0.600, where р<0.01).

Taking into account the peculiarities of security perception in the four subgroups of respondents, it is possible to classify them into four types: power-compensatory (subgroup 1); adaptive (subgroup 2); autonomous (subgroup 3); and exploratory (subgroup 4) (Figure 2).

The power-compensatory type is characterized by defensive behavior, which allows these people to create and retain a positive self-image, positive self-esteem. They strive to “protect” themselves from real or seemingly “negative living conditions” (to preserve the stability of their inner emotional state by pursuing security).

The adaptive type is marked by a desire to cope with information overload at the expense of perceptive categorization. The result is that the diversity of influential information is classified and simplified; this process can either help achieve a clearer understanding of things under evaluation or provoke the loss of significant data (apperception blindness) in the interest of retaining stable high self-esteem, the reproduction of which is a key regulator of everyday social behavior.

Figure 2. Specifics of Russians’ perceptions of “self ” positions in different situations of security.

The autonomous type is characterized by self-perceiving and self-evaluating on the basis of interpretations of one’s own actions. Any situation is seen as potentially possible. This sense of free choice encourages people’s readiness to overcome all barriers to achieving goals; such people consider themselves active “doers.”

The exploratory type can be recognized by their craving for a novel physical and social environment, by their acute sensations, risk seeking, desire to escape from security, readiness to endure information indefiniteness, and striving for “self-testing,” which results in risky behavior and the pursuit of danger.

Conclusions

The study conducted demonstrates that security is a principal component affecting the social perception of personality. Security is a complex, well-structured formation that depends on individuals’ psychological perceptions of their defensibleness, steadiness, and the confidence that they do or do not experience in a concrete situation.

Security acts as a substantive line of social cognition, a factor of social cognition, and a sociopsychological format of social cognition.

Therefore, security is a psychological formation that depends on one’s personal perception of the specifics of subjective reality. The results of the research make it possible to speak about consistent patterns in placing the images of the “secure self,” “the insecure self,” and the “now self ” in a semantic field. Based on an analysis of the data on the semantic differential of each group of respondents, a semantic field illustrating a model of ordinary consciousness and including “secure” and “insecure” world images was completed. The location of objects in the semantic field corresponds to values embedded in images of a safe and dangerous world that are characteristic of power-compensatory, adaptive, autonomous, and exploratory types.

The research conducted allows us to interpret security as an intricate, contradictory phenomenon combining a striving for changes and a fear of them. New and set-in-advance states provide information charged by sociohistoric experience, stereotypes, and ideas of the “right” world.

This research has realized just one aspect of the study of security, a multidimensional phenomenon. Further research is required to confirm the preliminary conclusions reached in this work and to single out new aspects for analysis.

References

- Aksyonova, Y. A. (2000). Simvoly miroustroystva v soznanii detei [Symbols of world order in children’s consciousness]. Yekaterinburg: Delovaya Kniga.

- Dontsov, A. I., & Perelygina, E. B. (2011a). Problemy bezopasnosti kommunikativnykh strategii [Security problems of communicative strategies]. Vestnik MoskovskogoUniversiteta. Seriya 14. Psikhologia [Moscow University Psychology Bulletin], 4, 24–31.

- Dontsov, A. I., & Perelygina, E. B. (2011b). Security problems of communicative strategies. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 4, 316–323. doi: 10.11621/pir.2011.0020

- Dontsov, A. I., Zinchenko, Y. P., & Zotova, O. Y. (2013). Notions of security as a component of students’ attitudes towards money. Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences, 86, 98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.532

- Dontsov, A.I., & Zotova, O. Y. (2013). Reasons for migration decision making and migrants’ security notions. Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences, 86, 76–81. doi: 10.1016/j. sbspro.2013.08.528

- Hirsh, E. D. (1988). Cultural Literacy. What Every American Needs to Know. N.Y.: Vintage Books.

- Klimova, S. G. (2002). Lomka sotsial’nykh identichnostei, ili “my” i “oni,” vchera i sevodnya [The break in social identities, or “we” and “they,” yesterday and now]. Otechestvenniye zapisky [Home Proceedings], 3, 106–122.

- Kozyrev, G. I. (2008). Vrag i obraz vraga v obshchestvennykh i politicheskikh otnosheniyakh [“Enemy” and “enemy image” in social and political relations]. Sotsiologicheskiye Isslledovaniya [Sociological Research], 1, 31–39.

- Mushakoji, K. (1991). Politicheskaya i kulturnaya podoplyeka konfliktov i global’noe upravlenie [Political and cultural reasons for conflicts and global management]. Politicheskiye Issledovaniya [Political Research], 3, 3–26.

- Panarin, S. A. (1998). Bezopasnost’ i etnicheskaya migratsiya [Security and ethnic migration]. Pro et Contra, 4, 11–17.

- Petrenko, V. F. (2010). Osnovy psikhosemantiki[Basics of psychosemantics]. Moscow: Eksmo.

- Rothschild E. (1995). What is Security? Daedalus, 124, 53–98.

- Smirnov, S. D. (1985). Psikhologiya obraza:Problemi aktivnosti psikhicheskovo otrazheniya [Thepsychology of image: Problems of mental-reflection activity]. Moscow University Press.

- Soboleva, M. A. (2001). Psikhosemantika predstavleniya o drugom cheloveke [Psychosemantics of the perception of another person] (Unpublished candidate’s thesis). St. Petersburg University.

- Zinchenko, Y. P., & Zotova, O. Y. (2013). Social-psychological peculiarities of attitude to self-image in individuals’ striving for danger. Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences, 86, 110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.534