Utility of Concept Cartoons in Diagnosing and Overcoming Misconceptions Related to Photosynthesis

Published: June 10, 2007

Latest article update: Dec. 27, 2022

Abstract

In this study, the effectiveness of concept cartoons in diagnosing and overcoming students’ misconceptions related to photosynthesis subject was examined. Firstly, the literature has been thoroughly examined and misconceptions about photosynthesis subject have been listed and then grouped. Concept cartoons related to these groups have been prepared and were introduced to the students in order to identify their misconceptions. Similar misconceptions as in the literature have been found. Then, new concept cartoons addressing to elimination of these misconceptions have been prepared and were used in class discussions. The excerpts from these discussions and after-class student interviews show that concept cartoons may be an efficient tool not only to identify student misconceptions but also to overcome them. The compatibility of this method (utilization of concept cartoon-based teaching) with constructivist approach was also discussed.

Keywords

Misconceptions, Photosynthesis, Concept Cartoons

INTRODUCTION

Cartoons and Education

Upon examination of the place of cartoons in the teaching and learning related literature, various purposes behind using them are noticed: Developing reading skills (Demetrulias, 1982), strengthening vocabulary repertoire (Goldstein, 1986), increasing problem solving abilities (Jones, 1987), developing writing and thinking abilities (De Fren, 1988), enhancing motivation (Heintzman, 1989), resolving conflict (Naylor & McMurdo,1990), identifying students’ attitudes toward science (Lock, 1991) and eliciting their implicit scientific knowledge (Guttierrez & Ogbom, 1992) are among them. Having examined students’ conceptualization of basic science concepts, the researchers who use cartoons in the “concept cartoon” framework (Novick & Nussbaum, 1978; Watts & Zylbersztajn, 1981; Nussbaum, 1997) examine alternative conceptions in the pictorial form. When literature is examined, it is seen that cartoons are utilized in various forms and structures, and teaching and learning outcomes may be said to be quite successful.

Concept Cartoons

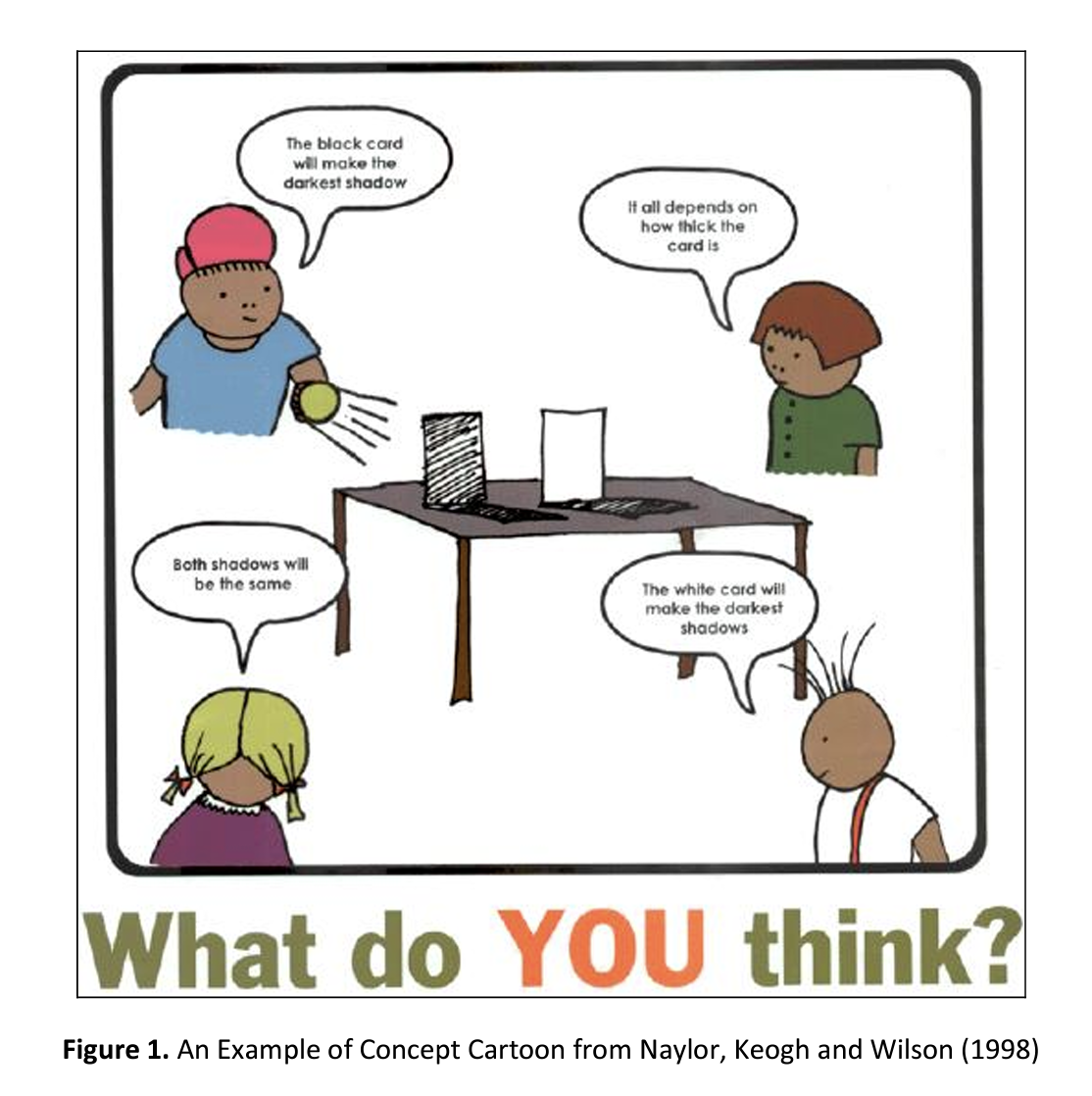

Concept cartoons were developed as a result of endeavour to enlighten the relationship between constructivist approach and epistemology & classroom applications (Keogh and Naylor, 1999). Excluding humour and satire attributions of common cartoons, concept cartoons combine visual elements with the texts written in the form of dialogues (Keogh and Naylor, 1999). Enriched with a specific science concept or subject, they are placed in the places where students have easy access. The portrayals of groups which are composed of 3 to 5 students and have different expressions or explanations are embedded. These student statements and dialogues, mostly in the form of dialogue boxes, include misconceptions and/or alternative conceptions (Figure 1). One of the most important characteristics of concept cartoons is the fact that amongst many statements raised by students in the cartoons exists —only- one scientifically acceptable explanation. Other statements -while scientifically incorrect- “are not ridiculously implausible and are often based on students’ experiences and/or intuitions” (Stephenson & Warwick, 2002, pp.136). The expressions and thoughts of interacting characters should be written as short as possible. As a result of the process outlined above, the sources of alternative concepts the students probably hold are —once identified- modeled in the cartoons so that they can be utilized in class activities targeted to eliminate them.

Concept Cartoons and Science Education

We have defined concept cartoons as depiction of dialogues in which 3 or more students are involved. Each of the characters in the concept cartoons are accompanied with dialogue boxes having different perspectives and statements. One of the statements in these dialogue boxes is the one which is accepted scientifically to be true; on the other hand, the rest are accepted to be not true —while the students may think otherwise. This situation is called “misconceptions” by educators and cognitive psychologists. In the literature they are also called as “preconceptions” (Hashweh, 1988/as cited in Bahar, 2003), “alternative framework” (Driwer & Easley, 1978/as cited in Bahar, 2003). In this study we preferred to use the terms “misconceptions” and “alternative conceptions” in order to name students’ problematic thought and inferences about a science concept or natural phenomena.

There are various ways of using concept cartoons in science courses. Kabapmar (2005), proposing that concept cartoons may be used as instructional material and teaching method in science courses, prepares concept cartoons related to matter and heat subject a) as an instructional material in the form of “poster” and “concept cartoon worksheet” strengthened by drill & practice questions b) as a teaching method; which are then successfully used in class discussions.

Keogh, Naylor and Wilson (1998) argue that concepts cartoons may be utilized as a method to increase society’s interest towards science besides being utilized as an assessment strategy. There are also researchers who claim that concept cartoons may be efficient tools in order to identify student misconceptions (Ingeу, Yildiz and Ünlü, 2006) and remedy them (Saka, et al, 2006). Concept cartoons, which apparently seem to be easy to prepare and design, need to carry following characteristics in order to have greater student success and motivation:

- Minimal amounts of text, so that they are accessible and inviting to learners (of any age) with limited literacy skills

- Scientific ideas are applied in everyday situations, so that learners are challenged to make connections between the scientific and the everyday

- the alternative ideas put forward are based on research that identifies common areas of misunderstanding, so that learners are likely to see many of the alternatives as credible

- the scientifically acceptable viewpoin will be included amongst the alternatives

- the alternatives put forward all appear to be of equal status, so that learners cannot work out which alternative is correct from the context. (Keogh, Naylor and Wilson, 1998).

Utilization of Concept Cartoons in Teaching

The researchers who examine the contribution of concept cartoons to teaching and learning process find that they a) help in eliciting student misconceptions in a short time b) provide participation of almost all students in class discussions, c) motivate and activate the students in order to advocate and support their arguments, and as a result d) eliminate their misconceptions (Keogh, Naylor & Wilson, 1998; Keogh & Naylor, 1999; Naylor, Keogh, DeBoo & Feasey, 2001; Stephenson & Warwick, 2002; as cited in Saka et al., 2006).

It is projected that concept cartoons will increase student motivation, focus their attention more on the courses, and provide constructivist learning environment where the students will participate in classroom discussions comfortably and enjoyably. According to constructivist approach, the environments where individuals socially interact are to be provided in order for meaningful and enduring learning. Especially in science and technology courses, the concept cartoons, targeting active enrollment of students, provide them social environment to express their ideas freely (Saka et al., 2006).

Dabell (2004) states the importance of social interaction and communication when concept cartoons are used cooperatively. Concept cartoons may also be used as a starting point to encourage students during class discussions and identify their prior knowledge (Bing and Tam, 2003).

As an alternative to class discussions, homogeneous and heterogeneous small group discussions are also presented as examples of how concept cartoons are used in class applications (Kabapmar, 2005). Kabapmar propose that the phases of concept cartoon based teaching as “introduction of cartoons”, “discussion about cartoons”, “investigation about ideas in the cartoons” and “re-interpretation of the ideas in the cartoons by taking the investigation findings into account”. The quality of in-class discussions, students’ opportunity to compare their ideas with the ones in the cartoons and the role of teacher during these processes are the factors that influence the success of concept cartoon-based teaching.

Naylor and Keogh (1999) argue that constructivist approach brings a need for new teaching and learning methods and exhibit concerns about teachers’ and students’ possible resistance towards these innovations. Contrary to their concerns, concept cartoon-based teaching method gave promising results: 85 prospective science teachers were enrolled in their 3- year long-term study. Opportunities for evaluating the use of concept cartoons were provided and student teachers were given chances to reflectively think about how concept cartoons might have been utilized in constructivist learning environment. Prospective teachers, in their study, found concept cartoons useful in identifying students’ prior knowledge, encouraging them in conducting investigations and implementation of a constructivism-rooted teaching and learning

Utilization of Concept Cartoons in Assessment

Keogh and Naylor (1997) argue that concept cartoons may be used as an efficient tool for identification of misconceptions by teachers and students themselves during the instruction and preinstruction. Kabapmar (2005) claims that concept cartoons may lessen negative effects of student anxiety about “giving incorrect answer” since it is not the student but the character in the cartoon who first raise the thought similar to his/her one. According to her, the student is not the one who expresses the erroneous idea but s/he is the one who only supports it; therefore, s/he will be able to participate in the activities more comfortably and express his/her ideas more freely.

The concept cartoons in the literature were mostly prepared on large cardboards where the characters in the cartoons express their ideas in the form of dialogues big enough to be seen form everywhere in the class (Stephenson & Warwick, 2002). The number of characters in them varies depending on the alternative conceptions the student may hold about the concept. Educators who would like to use concept cartoons may, therefore, utilize the literature about possible misconceptions the students may possess. While in the literature, concept cartoons are mostly prepared on posters, it has been suggested that they may also be prepared as “concept cartoon worksheets” (Kabapmar)

Misconceptions in Science Education

The literature of last decades shows that students possess different beliefs about scientific concepts than scientifically accepted ones. These different perceptions of concepts are mostly formed as a result of students’ daily life experiences. These conceptions, which are far away from being scientific, are called misconceptions (Bahar, 2003; Griffiths & Preston, 1992; Canpolat)

In the literature we can see that these conceptions are also referred as “alternative frameworks” (Driver &Erickson, 1983), “prior conceptions” (Anderson & Smith, 1987; Hashweh, 1988), “alternative conceptions” (Wandersee, Mintzes & Novak, 1994), “spontaneous knowledge” (Pines & West, 1986), and “children’s science” (Gilbert, Watt & Osborne, 1982)

Misconceptions are quite resistant to change (Fischer, 1985). Therefore, it is quite difficult to remedy them and to provide meaningful learning by using traditional teaching methods. For that reason, alternative teaching methods by means of what students’ prior knowledge are identified and their misconceptions are remedied are preferred. Concepts cartoons are amongst these alternative teaching methods, which highlight visual!ty.

Examination of the literature shows that students have a large number of misconceptions about photosynthesis (Bell, 1985; Wondersee, 1985; Anderson, Sheldon & Dub ay, 1990; Mason & Boscola; 2000; Ayas, Köse and Ta§, 2002; §ensoy et al., 2003; Tekkaya and Baler, 2003). These studies show that the students have misconceptions about definition and purpose of photosynthesis, nutrition of plants, chlorophyll, and the place of water.

The Purpose of the Study and Its Significance

The Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is

- to present the effectiveness of concept cartoons in diagnosing elementary students’ misconceptions in the subject of photosynthesis.

- to examine the role of concept cartoons in the elimination of identified misconceptions.

- in) to explore student views about concept cartoonbased teaching method.

The Significance of the Study

Literature survey shows that photosynthesis is a concept that elementary students have difficulties in comprehending and it is a concept about what they hold many misconceptions. Therefore, identifying and remedying these misconceptions have been aimed. Concept cartoons, being an efficient tool to overcome student misconceptions, and change public perception of science and attitudes of students, assumed to have positive role in remedying students’ misconceptions about photosynthesis concept. As a result, this study will provide contributions to literature in terms of providing instructional materials about photosynthesis subject and identifying and overcoming students’ misconceptions about photosynthesis.

METHOD

Sampling

This study has been conducted at an elementary school in Ankara, in the second semester of 2006-2007 school-year. The participants are 24 volunteer 8th grade students since the subject of photosynthesis is implemented in this grade level.

Implementation and Data Gathering

The activities, in the format of a regular science course, have been conducted under the responsibility of a science teacher during after-class hours. Literature has been thoroughly surveyed in order to list misconceptions about photosynthesis subject, which have then been used by the researchers in the design of concept cartoons by following steps outlined by Keogh, Naylor and Wilson (1998) we mentioned in the section 1.2.

The concept cartoons addressing to students’ misconceptions, then, have been presented to students and their ideas are questioned. In these one-to-one interviews, the students have mentioned about which ideas in the cartoons they are in favor of and detailed its reason. Especially the students who advocate alternative conceptions have been directed follow-up questions in order to probe their conceptual frameworks in more detail. Students’ misconceptions and explanations have been presented in the Findings part.

After the analysis of student pre-interviews, identified misconceptions have been listed (Table 2). In the second step of the study, new concept cartoons have been presented addressing to misconceptions listed in this table. These new concept cartoons have been presented to students by means of a projector in order better to provide opportunity for class discussion. All students, who have misconceptions or not, have participated in these discussions. This provided students opportunity to hear their friends’ arguments and question their own opinions.

The researchers, sitting at the back side of the class, passively observed the classroom activities and discussions and took notes about student-student, student-teacher dialogues. They have not involved in any classroom activities, and have not made any verbal interaction with students and teachers. The students, according to their teachers, were already familiar with discussion method. We think that this experience may have also influenced active participation of the students in class discussions.

After these classroom discussions, the students who have misconceptions (SWHM) have been interviewed about their pre-identified misconceptions and the classroom discussions they have involved in. The details of this interview have also been presented in the Findings part.

The data of this study stems from student interviews about the thoughts of the characters in the concepts cartoons during the pre-discussion period, researchers’ observation during class discussions and student interviews during the post-discussion period.

The students who have misconceptions are labeled as SWHMs (students who have misconceptions) and their ideas are presented in the Findings part. By means of this type of codification and classification, we found opportunity to compare student ideas before, during and after the discussion (Table 2). The data obtained from the interviews have been interpreted by presenting their relation to concept cartoons about photosynthesis.

Findings

Analysis of the data shows that elementary students in our sample have various misconceptions about photosynthesis. These misconceptions are similar to the ones that exist in the literature. The misconceptions that have been found in the literature and the ones that we obtained from our study are presented below.

Student Misconceptions about Photosynthesis in the Literature

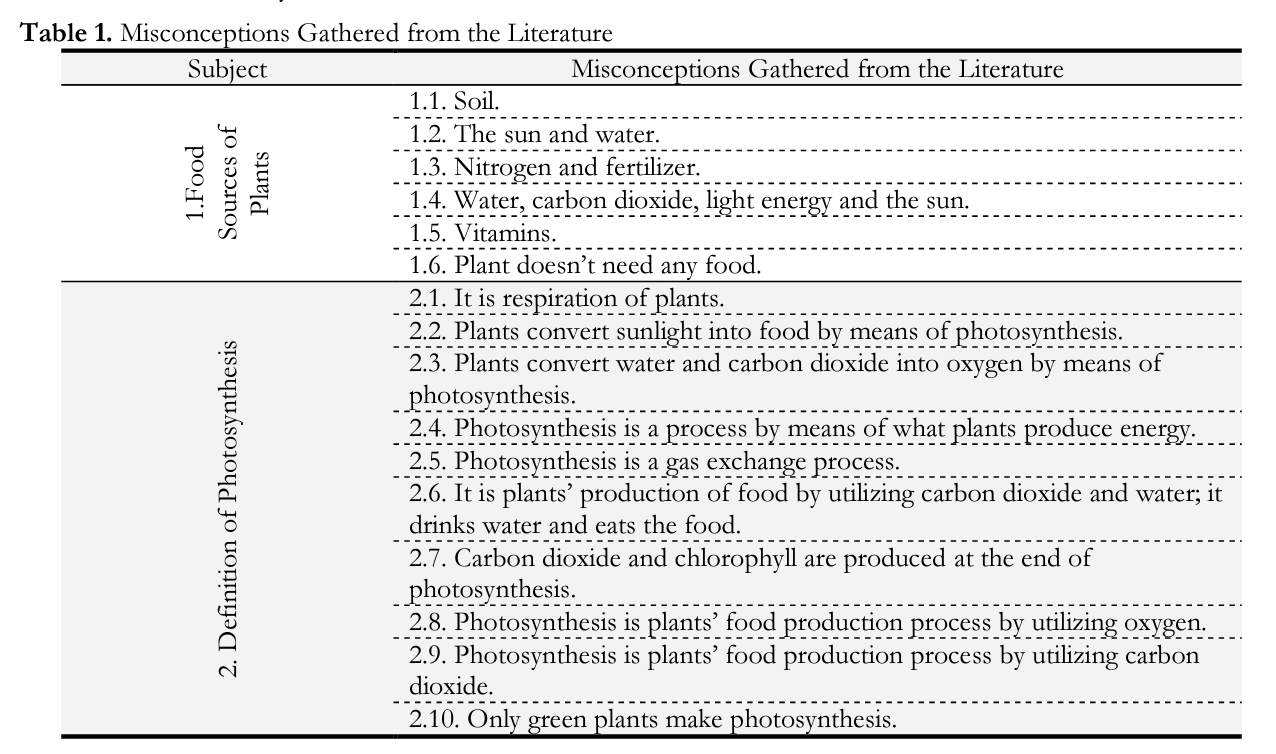

Literature has been surveyed before the conduction of the study. The misconceptions obtained from this survey have been classified into two groups as presented in the table 1.

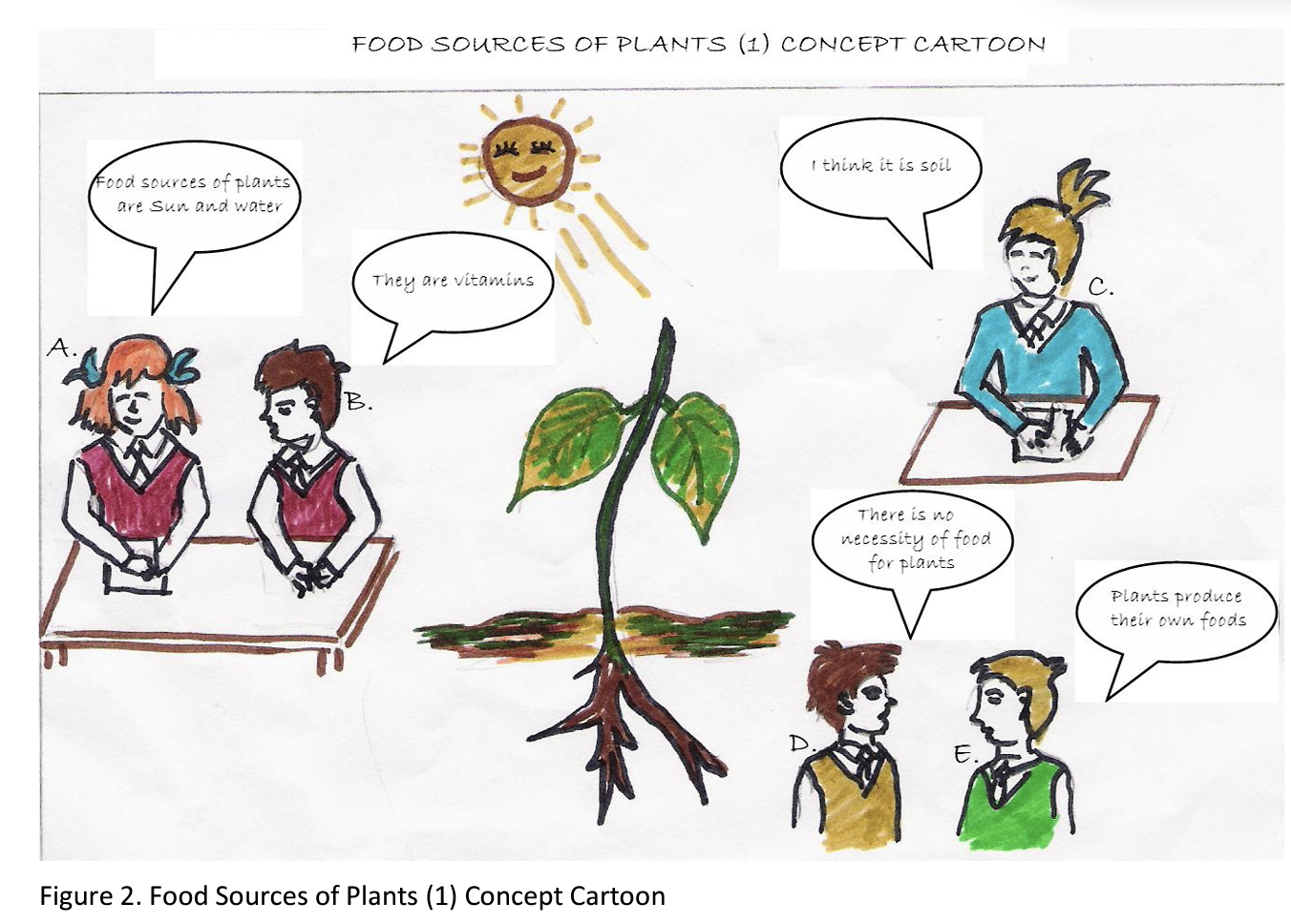

Interview Findings about Food Sources of Plants

In the excerpts below can be seen student ideas which have been obtained during one-to-one student interviews (pre-discussion period interviews) aided by the concept cartoons designed to address Food Sources of Plants. (R: Researcher; T: Teacher; SC: Student in the class; SWHM: Student who have misconception)

SWHM 1: I think A is right

R: Why:

SWHM 1: well... if the plants are waterless, its leaves wrinkle and then desiccate., my mom used to place the flowers in front of windows which face the sun and say that they need the sun. If they don’t get enough sunlight they will get sick and wither even if we water them...

SWHM 2: I think A is right...

R: Why?

SWHM 2: The leaves of trees get desiccate and fall in the winter since they don’t see the sun enough. The clouds hide the sun; the sun heats less. Therefore, if there is no Sun, then the plants can’t get energy..they stay dry until the summer. The flowers at our homes don’t get desiccated because there is light at nights and it is like the Sun.

SWHM 3: I think if there were no soil, then the plants would not get any food. If we take flowers apart from the plants, they will eventually die even if we place them into water.

SWHM 4: My mother added vitamins since the flower was foodless; I think plants take their food from the soil.

SWHM 5: I don’t think that plants need any food. Because they don’t move and their roots are tied to soil [implying that they don’t need food because they get the food from soil]. Soil is necessary for them. And they also die if we don’t water them.

SWHM 6: I think two persons are right here.. May I select two persons? If then, I think A and E are right, because the plants cannot live without sun, water and soil; all of them is necessary. I mean they die if there is no Sun energy, if we don’t water them and if we take them apart from the soil.

6 of the students who were interviewed have misconceptions as can be inferred from the statements above. It seems that the students who interpret their daily life experiences arrive at misconceptions that the plants get their food from environment as the animals do. SWHM 3 and SWHM 4 argue that the plants get their food from soil. These misconceptions prevent students from comprehending that the plants are livingbeings that produce their own food.

In this first step, it has been observed that usage of concept cartoons provided students comfortable environment to express them. One of the reasons, and we think the strongest one, of it is the student perception that they advocate the expressions of the characters in the cartoons, not their own ones. Another noticeable conclusion of this first step is the similarity between the misconceptions in the literature and the ones we found by means of concept cartoon-aided interviews.

Interview Findings about the Definition of Photosynthesis

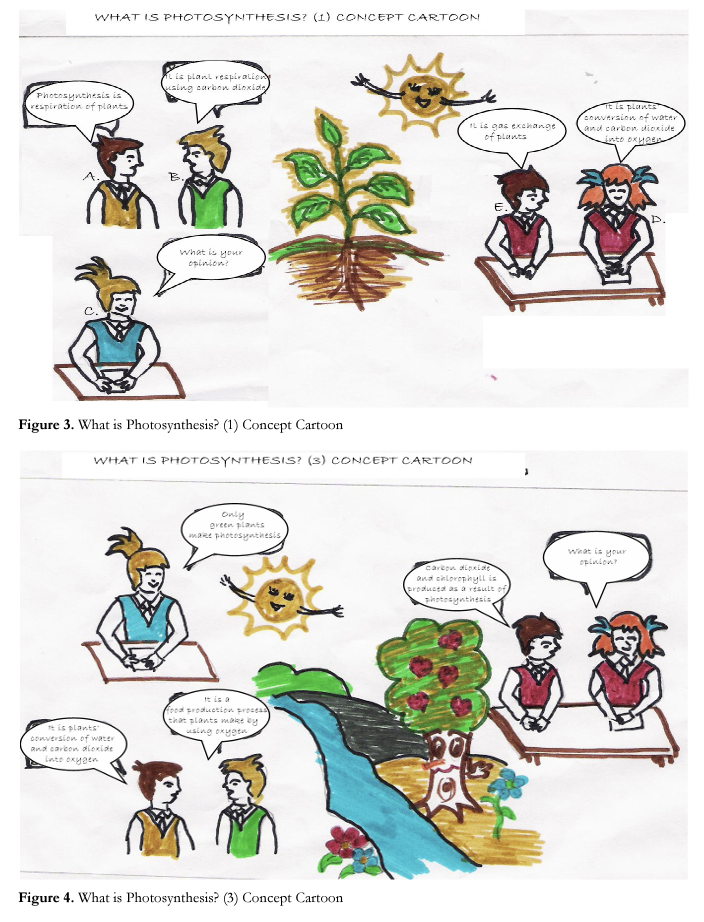

Since the misconceptions in Table 1 outnumber the characters in a recommended concept cartoon, we classified misconceptions about the definition of photosynthesis into two groups: “Respiration and Gas Exchange” and “Food and Products”

Misconceptions and Concept Cartoons about Respiration and Gas Exchange

These misconceptions are numbered as 2.1., 2.3., 2.5., 2.9. and 2.10. in the Table 1. These conceptions related to definition of photosynthesis imply that photosynthesis may be understood as a respiration and gas exchange. The Concept Cartoon labeled as “What is Photosynthesis” (1) has been designed by taking these misconceptions into account (Figure 3)

SWHM 1: E is right...

R: Why?...

SWHM 1: It is a gas exchange...during the day, when photosynthesis occurring, the plants take carbon dioxide., while at night —the opposite- they take oxygen and release carbon dioxide from their leaves.

SWHM 3: By means of photosynthesis, the plants convert water and carbon dioxide into oxygen... by means of that, green plants produce oxygen which is necessary for humans and animals,

SWHM 6: The plants inhale and exhale by means of photosynthesis. During the day they take carbon dioxide and release oxygen. And at night they use up oxygen.

SWHM 7: Photosynthesis is plants’ respiration by using carbon dioxide.

SWHM 8: It is plants’ process to convert carbon dioxide into oxygen. That means it is a kind of respiration. Oh, there should also be sunlight; I mean it happens during the day.

SWHM 9: It is exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen which is done by only green plants. Green plants take carbon dioxide and release oxygen...then we can breathe as well.

Some of the students who have been identified to have misconceptions during the interviews about Food Sources of Plants have also been identified to have misconceptions during this interview aided by concept cartoons about definition of photosynthesis: The students SWHM 1, SWHM 6 and SWHM 7 may be said to perceive the process as a gas exchange in the interviews about the definition of photosynthesis. The misconceptions similar to these students’ misconceptions (respiration and gas exchange) have also been stated by some students who had said that plants had synthesized their own foods themselves. Combining these apparently conflict, we may infer that some students have just memorized the formula of photosynthesis without understanding the fundamentals of it; and they confused the role of carbon dioxide, sun light, water and oxygen during the process of photosynthesis. The students SWHM 2 and SWHM 5 tried to define photosynthesis themselves and they possess misconception in this concept as well. Since we think that their statements are more about Food and Products, they have been mentioned in the following part.

Misconceptions and Concept Cartoons about Food and Products

These misconceptions are numbered as 2.2, 2.4., 2.6., 2.7. and 2.8 in Table 1. The Concept Cartoon labeled as “What is Photosynthesis” (3) has been designed by taking these misconceptions into account (Figure 4),

SWHM 2: I think the plants convert the sunlight... hmmm... the energy of sun into food by means of photosynthesis. Thus, green plants produce their foods to sustain their lives by using carbon dioxide in the air.

SWHM 5: Photosynthesis is a procedure by means of what plants produce energy. By means of sunlight, carbon dioxide is divided into its molecules.. I mean a reaction occurs and energy is released. That happens in the leaves.

SWHM 10: Photosynthesis is the production of oxygen by means of plants’ synthesis of water and carbon dioxide... that means A is right... but I think there is effect of sun as well... then the oxygen which is necessary for us is produced.

SWHM 11: It is plants’ production of carbon dioxide and chlorophyll... eer... chlorophyll already exists but by means of photosynthesis more of them are produced... then plants converts carbon dioxide into oxygen...and then give it out.

Some of the students who have been identified to have misconceptions during the interviews about Food Sources of Plants have also been identified to have misconceptions during this second interview about definition of photosynthesis aided by concept cartoons.

The students SWHM 2, SWHM 5 who have been identified to have misconceptions about food sources of plants and the students SWHM 10 and SWHM 11 may be said to comprehend that the process is about food or production of it. However, they confuse the relation between the reactants and products and state erroneous ideas and misconceptions about them.

Findings Obtained from In-Class Discussion

The science teacher, introducing the concept cartoons to students, addressed the questions like “which of the ideas do you support?”, “which one, do you think, is right”, “whose thought is correct?”. In order to encourage the students, the priority to talk during the discussions was given to the students who examined the cartoons more in detail. Researchers focused more on the behaviors and expressions of SWHMs and took more notes about them than the other students. Students, who were reluctant to express themselves and stated short sentences and sometimes a few sentences, started to express themselves freely and discussed enthusiastically as a result of teacher’s encouragement.

In the following section, we present some excerpts from the conversations between teachers, SWMHs and other students. Moreover, some behaviors of them during the discussions have been interpreted.

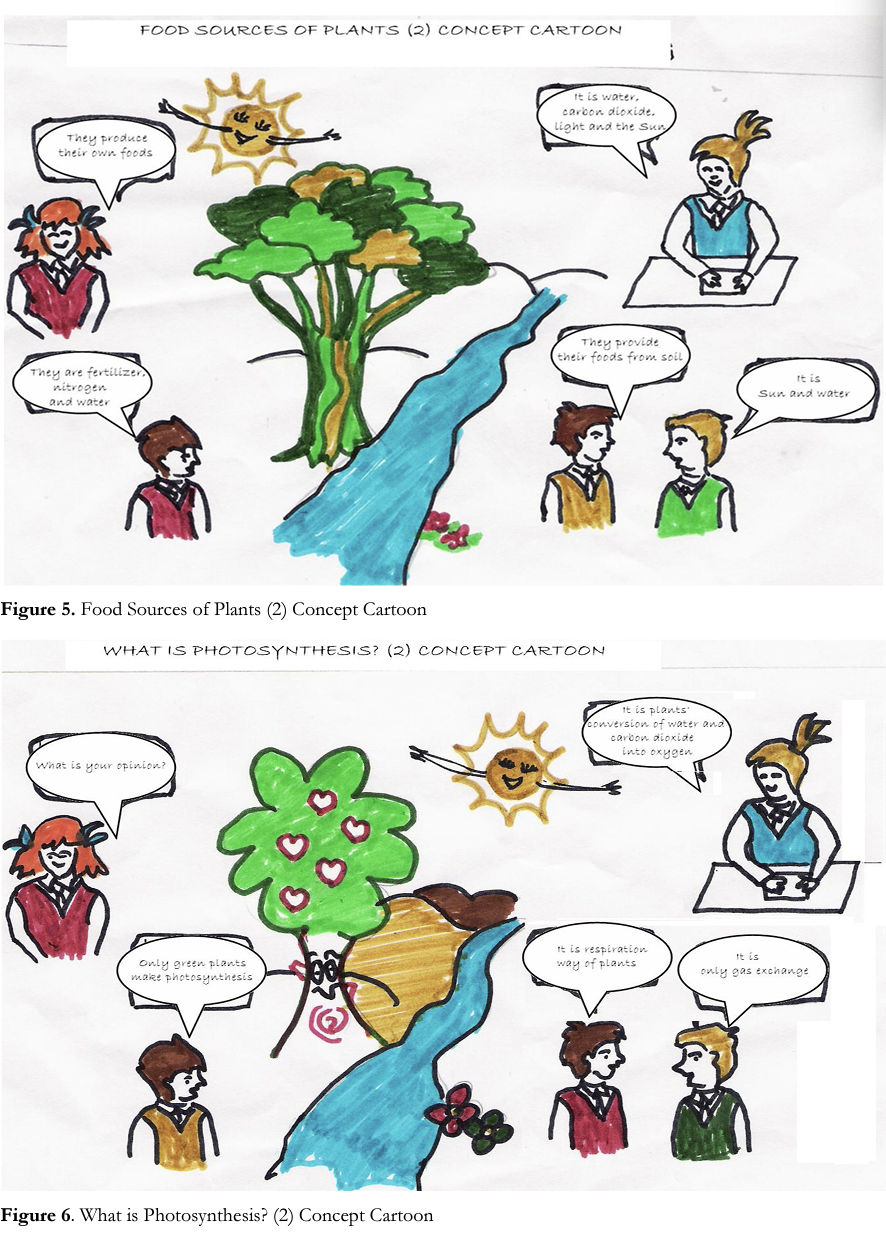

In-Class Discussion about Food Sources of Plants (2) Cartoon

After the projection of second concept cartoon about Food Sources of Plants on the wall, the students have contemplated -a while- about them and then the discussion has started.

T: You —all- see the picture on the wall., which one -do you think- is right? What do you think? What are the sources of plant foods do you think?

-after a while’s silence three students raise their hand [requesting permission to respond]

T: Yes, please, Mete.

SC (Mete): Well, I think plants produce their own foods..

T: Plants produce them?? How? (Pretending to be surprised)

SC (Mete): Of course. The plants produce their own foods by using sunlight, carbon dioxide and water.

SWHM 4: I think so as well.. The most important source of energy for plants is the sun. The plants provide their foods from sun, water and carbon dioxide.

SC (Orhan): (Interrupts him) but they produce it by using them.

SWHM 4: Yes but they cannot live without these three..and especially if there is no sun.

SWHM 3: The soil is very important for the plants as well. Thy cannot live without soil., that means they get some of their foods from the soil.

SC (Ah): Plants only gets minerals from the soil.

SWHM 4: I think SWHM 3 is right. I mean soil is very necessary for food..Due to lack of food, my mother added vitamins to her flowers’ soil..and it has become vivid. That means the plants gets their food from the soil.

SWHM 3: Yes, my uncle adds fertilizer to soil since he wants it to get richer. When it is added, he says, the soil is more productive.

SC (All): Yes but the plants take minerals from the soil, [they do] not [take] food. Then they use it to store their food.

SWHM 3 and 4: So, you say, the soil is not necessary? (both are excited a little)

SC (All): Noo, of course it is necessary but they don’t take food from the soil; they produce it.

In this second part of the study, in-class discussions about the characters in concept cartoons, some of the students have participated in the discussions while the others followed them by paying more attention. After the introduction of science teacher, the students started to express their ideas about the cartoons and the subject. All, Mete and Orhan were already identified as the students who didn’t have any misconceptions about the sources of plant foods. These students have taken the role of correcting and designing the discussion without being aware of it. While the students SWHM 3 and SWHM 4 have attended to in- class discussion, the other SWHMs preferred to listen to them. Cognitive conflict of both participating and following students has been targeted during this stage.

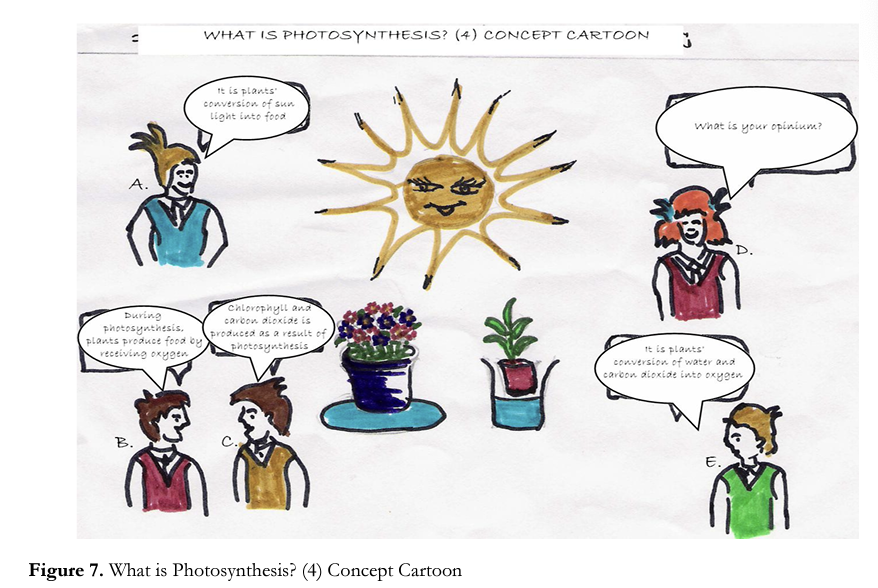

In-Class Discussion about the Concept Cartoons “What is Photosynthesis (2) and (4)

After a short introduction of the science teacher, the students have started to discuss the concept cartoons, with higher motivation this time due to their experience in the previous discussion. While the concept cartoon “What is Photosynthesis” was projected on the wall, it has been replaced with the concept cartoon “What is Photosynthesis (4) during ongoing discussion without giving correct definition of photosynthesis at each case. Some excerpts and interpretations about these discussions have also been presented in the paragraphs below, each are placed below the cartoons they are belong to.

The science teacher and the researchers realized that some students paid great attention to discussions but were reluctant to raise their voices. The teacher, therefore, tried to give these students priority in order to provide participation of them.

T: Yes, we were defining photosynthesis. Who would like to tell it?

SC (Aysje): I know we defined it but I cannot recall it exactly. But it was a chemical process..there were reactants and products...

SWHM 3: Yes.. Plants convert water and carbon dioxide into oxygen by means of photosynthesis. Thus, they respire and produce oxygen for us.

SC (Orhan): But I don’t think that they produce oxygen. T: What else, do you think, they produce SWHM 3?

-SWHM 3 thinks a while quietly

At this moment the researchers projectile the concept cartoon “what is photosynthesis (4)” on the wall. After reading the dialogue boxes and a while’s silence, the discussion commences.

SC (AH): They produce food, don’t they?

T: Are you sure?? Do you think so as well SWHM 3?

SWHM 3: (Pauses a while, examines the cartoon one more) yes, they may..

SWHM 2: Then, E and A must be right. I mean it is plants’ conversion of water and carbon dioxide into food by using sun light.

SC (AH): Of course. Sunlight is absorbed by leaves and then reacts with the carbon dioxide and water that exist there. And then by reaction, food is produced.

SC (Gonca): And, there was something called chlorophyll...

T: Chlorophyll??

SC (Gonca): Yes.. Chlorophyll on the leaves is quite important for photosynthesis as well.

T: Why do you think so?

SC (Gonca): Because they captures sunlight and... hmmm... absorb it.

T: So,, as a result, what do you think what photosynthesis is, guys?

T: Yes, please SWHM 7?

SWHM 7: Well, I used to know it as... hmmm... respiration of plants.

SWHM 5: I used to think that energy is produced as a result of photosynthesis. But it looks like it is the reverse. I mean plants take energy and produce food. That means I remembered it wrong.

T: So, what is it?

SC (Ali): It is the production of food by means of reactions of water and carbon dioxide activated by sunlight captured by plants on their leaves.

[After this short definition, the teacher ends the discussion and the activity.]

In this part of in-class discussions about the dialogues in the concept cartoons as well did some students actively participate while some students preferred to follow with only great attention. The teacher tried to encourage these timid students and gave them opportunity to talk. This endeavour has resulted in the participation of some of these students. Aysje expressed her ideas about the concept cartoon “What is Photosynthesis (2)”. While her response was not exactly correct, she raised the issues such as chemical reactions, reactants and products. The student SWHM 3, who got encouraged by her statements, expressed his ideas and mentioned about oxygen. After Orhan mentioned that it is not only oxygen what is produced during photosynthesis, the teacher directed the question to SWHM 3, asked what else had been produced. While SWHM 3 was thinking quietly, the researcher replaced the concept cartoon, thinking that the definition is related to Foods and Products.

Amongst the students who examine the concept cartoon “What is Photosynthesis (4)”, Ali, opens the discussion about Food Production. Teacher asks SWHM 3 whether he thinks the same. While the discussion goes on in this manner, Gonca has brought the concept of chlorophyll into discussion. At this moment, the students SWHM 7 and SWHM 5 stated that they realized that they had misconceptions about these concepts. Then, the teacher required the students to define photosynthesis in a more complete and correct way. After the short definition of Ali, the discussion has been closed.

The target of this phase was raising self-awareness and self-correction of students by means of active and passive participation of them during the discussions about the definition of photosynthesis. Examination of dialogue excerpts shows that we have approached to achieve this aim.

The Findings about the Interviews after the Activities

The Questions Addressed to the Students during the Interviews after the Activities

- Do you like the cartoons?

- What do you feel about implementation of this subject in this way? (Follow-up questions: Have you enjoyed it? Was it boring?)

- What are the food sources of plants?

- What is photosynthesis?

*5. Do you remember what you told me during the first interview I have done with you (Explanation: The interview about cartoons shown before in-class activity)

- Do you think that the character you have supported is correct?

5.b. When did you realize it?

* (5th question has only been asked to the students who were identified as SWHM)

22 of 24 students have commented positively about the cartoons. These students have stated that they enjoyed cartoons and argued that using them in the class made them more dynamic. The teacher also mentioned verbally that utilization of concept cartoons as a tool increased the participation of students. Only 2 students (SWHM2 and SWHM 6) mentioned that they didn’t like cartoons and said that they got bored when they examined them. They, moreover, stated that this method has let them make mistakes, and this had disturbed them.

The responses of SWHMs to the questions that has only been asked to them causes us to think that it is not incorrect to conclude that using concept cartoons as a means in and a method for science education is important and efficient for student self-awareness and self-correction. Some excerpts from their responses are as follows:

SWHM 1: I realized my mistake just after the fist interview. I thought it was correct but when I went home and examined the books related to photosynthesis...

R: That means you investigated for that?

SWHM 1: Yes..it turned out to be I remember it wrong. I thought that the plants had to get food like other living-beings. But it was wrong. The plants produce their foods themselves by using sunlight, water and carbon dioxide. Indeed, our teacher had mentioned about that; I don’t know why but it was stored in my mind differently.

SWHM 3: I was thinking that the plants did only respire by means of photosynthesis. Not the way we, humans, do of course; they takes carbon dioxide and release oxygen. This is indeed correct but I didn’t know that they produced food.

R: When did you realize it?

SWHM 3: When I mentioned about it, my friends oppposed it. I discussed it with Ali and Mete during the class. I realized at that moment that I didn’t learn this subject completely. Then I asked it to my science teacher, she gave me a book..the book was teaching with pictures..! examined it.

SWHM 4: Soil is extremely important for plants but they don’t take their foods from the soil. They stores the food produced during the photosynthesis .. photosynthesis made with the substances they received from the soil by means of water. Indeed, I used to think that the plants live by means of sun and the food they take from the soil..and of course, it wouldn’t happen without water.

R: So, when did you realize that you were wrong?

SWHM 4: During the second cartoon... when I read the word photosynthesis, I began to understand my wrong... when listening to my friends during discussions.. I realized at that time as well.

SWHM 5: When my friends were discussing about it, I realized that I knew wrong about that. Plants also need food in order to further their lives, not only moving-beings..I understood this.

SWHM 6: I understood the discussions went in the class but I got bored.

SWHM 7: I used to think that plants respire by means of photosynthesis but I have now learned that it is not the case. When the teacher let my friends discuss about it, I have better learned that photosynthesis is the production of food.

SWHM 8: When I listened to my friends during the first discussion in the class, I realized that I was not correct: The sun is not enough alone. They mentioned about carbon dioxide and oxygen. I knew about them but I was thinking that the most important one is the sun.

SWHM 10: I had said that the oxygen we respire was being produced by plants during photosynthesis. Indeed this is correct but I learned that this was not the only task of photosynthesis. The leaves synthesize glucose for plants during photosynthesis. During the reaction of photosynthesis, oxygen comes out on the side on products. I have investigated it from the books and internet. But I have better comprehended it when my friends discuss about it in the class.

It has been observed that during these afterdiscussion interviews, the students were more comfortable in expressing their ideas than they were in the pre-discussion interviews. When we examine their statements, it can be seen that some SWHMs felt a need to think and investigate about their responses since they doubted about their responses during the first interview. Some other SWHMs, on the other hand, have stated that they became aware of their wrong during the participation in and listening to in-class discussions.

During the after-class discussions, all students correctly responded to the questions about the food sources of plants and definition of photosynthesis. During these interviews, the students stated that plants produce their own food and they are classified as producers amongst all living-beings. While a small number of students expressed that they understood it, it seems that it does not go further then structural understanding and as a result their understanding is problematic. However, we can conclude that most of the students have overcome their misconceptions about this subject.

CONCLUSION, DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Discussion

A survey of literature shows that students have large number of misconceptions about photosynthesis (Bell, 1985; Wondersee, 1985; Anderson, Sheldon & Dub ay, 1990; Mason & Boscola; 2000; Ayas, Köse and Ta§, 2002; §ensoy et al., 2003; Tekkaya and Baler, 2003). Fischer (1985) states that misconceptions are quite resistant to change and therefore they are difficult to be overcome by traditional methods. This situation impedes meaningful learning of students. In this study, therefore, the usefulness of concept cartoons as an instructional tool and a teaching method (Kabapmar, 2005) in diagnosing and remedying misconceptions about photosynthesis has been examined.

Ingey, Yrldiz and Ünlü (2006) propose that concept cartoons are effective tools in eliciting students’ misconceptions and 8aka et al. (2006) state that they are influential in remedying these misconceptions. The findings of our study are quite compatible with the findings of literature and support them. The assertions of many researchers (Keogh, Naylor & Wilson, 1998; Keogh & Naylor, 1999; Naylor, Keogh, DeBoo & Feasey, 2001; Stephenson & Warwick, 2002; cited in 8aka et al., 2006) which have been supported during our study are: concept cartoons (1) help in elicitation of student misconceptions in a short time, (2) provide opportunity for students’ discussion about the causes of these misconceptions, (3) create an environment where all students participate during class discussions, activate them to support their ideas, and consequently (4) remedy their misconceptions. Both the findings of class discussions and student-interviews, and observations of researchers show that this study is compatible with the aims in the literature. Especially high number of active participation of students during in-class discussions, their comfortable way of expressing their ideas, and probing students’ misconceptions in a short time are amongst the most important results of this study. Moreover, according to interview and observation results, the discussions aided by concept cartoons are identified to be enjoyed by the students and enhanced their motivation. This findings are parallel to the ideas of Saka et al. (2006) who state that concept cartoons in science courses make student attention focus on the subject, enhance motivation, makes a visually-supported discussion environment where students enjoy the teaching/leaming and exchange their ideas and construct their knowledge.

Dabell (2004) mentions about the importance of social interaction and communication created when concept cartoons are utilized in a cooperative way. This is also compatible with our findings where in-class discussions and especially participation of both SWHMs and SC’s during all process provided enhancement of in- class interaction and communication. Similar to Naylor and Keogh (1999) study, this study has been useful in probing students’ ideas, encouraging them and utilizing constructivist approach during teaching.

Conclusion and Educational Implications

Comparison of findings of this study and misconceptions about photosynthesis in the literature shows that concept cartoons may be utilized in the identification and elimination of misconceptions. The table below presents comparative view of the misconceptions found in the literature and the misconceptions identified and eliminated by means of concept cartoons in this study.

Examination of the table above shows that the misconceptions found in this study are compatible with the misconceptions in the literature and the numbers of misconceptions which have been remedied are quite high. This shows that concept cartoons may be used for this aim. However, there are misconceptions which couldn’t be identified and which couldn’t be eliminated. Further studies should focus on concept cartoons about these misconceptions.

Another finding of this study is that it can be utilized in science education due to its compatibility to constructivist approach, its success in activating students, in identifying and eliminating misconceptions which are resistant to change. Therefore, more studies about concept cartoons are to be conducted addressing to elimination of misconceptions and their results are to be discussed. Since misconceptions are resistant to change, diagnosis and elimination of them is crucial. Individual differences of students are to be paid great attention in these studies. Then, it is possible to conduct more student-centered studies. Moreover, it may be quite beneficial to embed concept cartoons into textbooks after identification of student misconceptions for particular subjects.

Intelligence is a concept explaining all intellectual powers people have (Stoddard, 1956:5). “Intelligence is the power of adaptation to environment in new and surprising conditions, the power of abstraction and problem solving (Selyuk, 1999: 63). Binet defines intelligence as the capacity of reasoning, decision making and self-criticism (Toker et al., 1968:64). Thorndike defines intelligence as the ability to react positively in terms of the reality or phenomena (Toker et al., 1968:64).

Acknowledgement: On account of valuable contributions in drawing the cartoons, we thank to primary art teacher Hawa TASKIN BAYRAM

References

- Anderson, C.W., Sheldon, Т.Н. & DuBay, J. (1990), “The Effect of Instruction on College Nonmajors’ Conceptions of Photosynthesis and Respiration”, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 27(8), p.761-76

- Anderson, O.S., Smith, L.J., (1987), Peer Tutors in a College Reading Laboratory: A Model That Works, Reading Improvement, v24, n4, p.238-47

- Ayas, A., Köse, S., Ta§, E., (2002), Bilgisayar Destekli Ogretimin Kavram Yanilgilan Uzerine Etkisi: Fotosentez, Pamukkale Universitesi Egitim Fakültesi Dergisi, Yil 2003 (2) Sayi:14

- Bahar, M, (2003), Misconceptions in Biology Education and Conceptual Change Strategies, Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 3(1), p.55-64

- Bell, B., (1985), Students’ Ideas About Plant Nutrition: What are They?, Journal of Biological Education, vl9, p.213-218

- Bing, K.W., Tam, C.H., (2003), The Multi Use Of Cartoons In Enhancing Teaching and Training: Usage Of Cartoons that are Readily Available in Local Newspaper in Malaysia. Jumal Pengurusan dan Kepimpinan Pendidikan: Institut Aminuddin Baki

- Canpolat, N. (2006). Turkish Undergraduates Misconceptions of Evaporation,Evaporation Rate, and Vapour Pressure, Internatlonal Journal of Science Education, 28(15), 1757- 1770.

- Dabell, J., (2004), Concept Cartoons, Junior Education, July 2004, Scholastic

- De Fren, M., (1988), Using Cartoons to Develop Writing and Thinking Skills, Social Studies Journal, 79, 221-224

- Demetrulias, D.A.M., (1982), “Gags, Giggles, Guffaws: Using Cartoons in the Classroom” Journal of Reading, v26 nl p.66-68

- Driver, R., Easly, J., (1978), Pupils and Paradigms: A Review of Literature Related to Concept Development in Adolescent Science Students, Studies in Science Education, (5), p.61-84

- Driver, R, Erickson, G., (1983), Theories-in-Action: Some Theoritical and Emprical Isues in the Study of Students’ Conceptual Framework in Science, Studies in Science Education, 10, p.37-60

- Fisher, К. M., (1985), A Misconception in Biology: Aminoacids and Translation, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, v22, p.53-62

- Gilbert, J.K., Osborne, R.J., Fenshman, P.J., (1982), Children’s Science and Its Consequences for Teaching, Science Education, 66, 4, 623-633

- Gilbert, J.K, Watts, D.M., Osborne, R.J., (1982), Students’ Conceptions of Ideas in Mechanics, Physics Education, 17, p.62-66

- Goldstein, B., (1986), Looking at Cartoons and Comics in a New Way, Journal of Reading , 29 (7), p.657- 661.

- Griffiths, A.K, Preston, K.R., (1992), Grade-12 Students' Misconceptions Relating to Fundamental Characteristics of Atoms and Molecules, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, v29, n6, p.611-28 Guttierrez, R, Ogborn, J., (1992), A Causal Framework for Analysing Alternative Conceptions, International Journal of Science Education, 14, p.201-220.

- Hashweh, M., (1988), Descriptive Studies of Students' Conceptions in Science, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, v25, n2, p.121-34

- Heintzmann, W., (1989), Historical Cartoons: Opportunities to Motivate and Educate, Journal of the Middle States Council for Social Studies, 11, p.9-13.

- Ingey, §., Yildiz,. І., Ünlü, P., (2006), Kavram Karikattirlerinin Kavram Yamlgisi Tespitinde Kullanilmasi: Düzgün Dairesel Hareket, VII. Ldusal Fen Bilimleri ve Matematik Egitimi Kongresi, 6-8 Eylül 2006, ANKARA

- Jones, D., (1987), Problem Solving Through Cartoon Drawing, in R. Fisher (Ed.), Problem Solving in Primary Schools, Oxford: Basil Blackwel

- Kabapmar,E, (2005), Effectiveness of teaching via Concept Cartoons from the Point of View of Constructivist Approach (Yapilandirmaci Ogrenme Sürecine Katkilan Ayisindan Fen Derslerinde Kullanilabilecek Bir Ogretim Yöntemi Olarak Kavram Karikatürleri), Kuram ve LTygulamada Egitim Bilimleri (KLTYEB) / Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, v5 nl, p.101-146

- Keogh, B., Naylor, S., (1997), Starting Points for Science (Sandbach: Millgate House)

- Keogh, B., Naylor, S., (1999), Concept Cartoons, Teaching and Learning in Science: An Evaluation, International Journal of Science Education, v21, n4, p.431-46 '

- Keogh, B., Naylor, S., de Boo, M., Feasey, R, (1999), Formative Assessment: Using Concept Cartoons: Initial Teacher Training in the LT<, Paper presented at the 2nd Conference of the European Science Education Research Association Conference, Kiel, Germany. August 1999.

- Keogh, B., Naylor, S., Wilson, C., (1998), Concept Cartoons: A New Perspective on Physics Education, Physics Education, v33 n4 p219-24

- Lock, R, (1991), Creative Work in Biology -A Potpourri of Examples. Part 2: Drawing, Drama, Games and Models, School Science Review, v72, 11261 p.57-64

- Mason, L., ve Boscolo P., (2000), Writing and Conceptual Change. What changes?, Instructional Science, 2, p.199-226

- Naylor S., Downing, B., Keogh B., (2001), An empirical study of argumentation in primary science, using Concept Cartoons as the stimulus. Third International Conference of the European Science Education Research Association. Thessaloniki, Greece

- Naylor, S., Keogh, B., de Boo, M., Feasey, R, (2001), Formative Assessment Using Concept Cartoons: Initial Teacher Training in the LT<, in R. Duit (Ed.), Research in Science Education, Past, Present and Future, p.137-142, Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer

- Naylor, S., McMurdo, A., (1990), Supporting Science in Schools (Timperley: Breakthrough Educational Publications).

- Novick, S., Nussbaum, J., (1978), Junior High School Pupils' Understanding of the Particulate Nature of Matter: An Interview Study, Science Education, v62, n3, p.273-81

- Nussbaum, M., (1997), Cultivating Humanity: A Classical defence of Reform in Liberal Education. Cambridge, Mass

- Pines, A.L., West, L.H.T., (1986), Conceptual Lhiderstanding and Science Learning An Interpretation of Research within a Sources-of- Knowledge Framework, Science Education, v70 115 p583-604

- Saka, A., Akdeniz, A. R, Bayrak, R, Asilsoy, Ö., (2006), “Canlilarda Enerji Dönüijümü” Ünitesinde Kar§ila§ilan Yanilgilann Giderilmesinde Kavram Karikatürleriniii Etkisi, VII. LUusal Fen Bilimleri ve Matematik Egitimi Kongresi, 6-8 Eylül 2006, ANKARA

- Stephenson, P., Warwick, P., (2002), LIsing Concept Cartoons To Support Progression in Students' Lhiderstanding of Light, Physics Education, v37 n2 pl35 II ensoy, Ö., Aydogdu, M, Yildinm, Н.І., L^ak, M, Hanyer, A.H., (2003), llkögretim Ogrencileriniii (6., 7. ve 8. Similar), Fotosentez Konusundaki Yanlg Kavramlann Tespiti Ц/егіпе Bir Arajtirma, Milli Egitim Dergisi, yil: 33, sayi: 166

- Tekkaya, C., Balci, S., (2003), Ogrencilerin Fotosentez ve Bitkilerde Solunum Konulanndaki Kavram Yanilgilarmin Saptanmasi, Hacettepe Üniversitesi Egitim Fakültesi Dergisi 24 : s. 101-107

- Wandersee, J. H. (1985), Can the History of Science Help Science Educators Anticipate Students' Misconceptions?, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 23(7), p.581-597

- Wandersee, J.H., Mintzes, J.J., Novak, J.D., (1994), Research on alternative conceptions in science, in D.L. Gabel (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Science Teaching and Learning (pp. 177-210). New York: MacMillan.

- Watts, D. M., Zylbersztajn, A., (1981), A Survey of Some Children's Ideas about Force, Physics Education, vl6, n6, p360-65