A model to measure employee engagement

Published: Dec. 16, 2014

Latest article update: Dec. 6, 2022

Abstract

The objective of this article is to develop a model to measure employee engagement. In doing so, the article firstly develops a theoretical model by identifying employee engagement constructs from the literature. Secondly, identifying measuring criteria of these constructs from the literature, and thirdly, to validate the theoretical model to measure employee engagement in South Africa. The theoretical model consists of 11 employee engagement constructs, measured by a total of 94 measuring criteria. The empirical process of validation employed data collected from 260 respondents who study towards an MBA degree at two private business schools in KwaZulu-Natal. The validation process aimed to validate the variables that measure each of the constructs by determining statistically that the sample employed is adequate, use the Bartlett test to ensure the applicability of the data for multivariate statistical analysis; to validate the measuring criteria as relevant to employee engagement, and to determine the reliability of each of the employee engagement constructs in the model. All these objectives were met. This culminated in the final result, namely an adapted empirical model to measure employee engagement in SA. The model tested statistically to be a valid and reliable model. The research is of value to management in the private and public sector, academics and researchers

Keywords

Reliability, validity, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), employee engagement

Introduction

Employee engagement as managerial tool continues to gain momentum in modem management practices. However, before instilling any managerial decision-making on the positive influences that employee engagement can have in an organization, it is imperative to first determine by measuring the levels of engagement of employees within an organization.

Measuring employee engagement within an application setting within a structured measuring environment requires a validated and standardized measuring tool, or alternatively, a newly developed measuring tool that originates from the literature. This article deals with the measuring of employee engagement by developing a new conceptual model. The article develops the model on a strong literature basis, where after the criteria and constructs are validated statistically.

The application setting for the study is business managers in South Africa, and more specifically, managers in the process of post-graduate studies at two private business schools situated in KwaZulu- Natal (however, the respondents are not limited to one province because they are studying at study centers throughout South Africa).

1. Defining employee engagement

Employee engagement is gaining momentum and popularity, acquiring international attention as it has become an accepted belief that engaged employees feel a connection to their work which impacts positively on their performance. This is supported by Thayer (2008, p. 74) who agrees that the concept of employee engagement is rapidly gaining popularity, use, and importance in the workplace and that by identifying the factors that can increase employee engagement, employers can make strategic adjustments within their organizations to create a positive psychological climate for employees.

Despite the popularity of the term “employee engagement” in the workplace, a precise definition of the term remains elusive because of continued research and redefinition surrounding the topic. Describing employee engagement, however, is done by listing the definitions and views of a number of renowned authors such as Hughes and Rog (2008), Crabb’s research (2011) and Shuck and Reio (2013).

Hughes and Rog (2008, p. 749) state that employee engagement is a heightened emotional and intellectual connection that an employee has for his/her job, organization, manager, or co-workers that in turn influences him/her to apply additional discretionary effort to his/her work. Shuck and Reio (2013, p. 1) define employee engagement as the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral energy an employee directs toward positive organizational outcomes. They go on to operationally define employee engagement as a series of psychological states (cognitive, emotional and behavioral) ultimately representing an intention to act that encompasses motivation-like qualities.

Crabb’s research (2011, p. 27) defines employee engagement as a positive attitude held by the employee towards the organization and its values. His research states that an engaged employee is

aware of business context, and works with colleagues to improve performance within the job for the benefit of the organization. The organization must work to develop and nurture engagement, which requires a two-way relationship between employer and employee.

According to research conducted by Mone et al. (2011, p. 206) employee engagement is defined as an employees’ sense of purpose and focused energy that is evident to others through the display of personal initiative, adaptability, effort, and persistence directed toward the organization’s goals. In their research they describe employee engagement as defined by Gebauer and Lowman (2009 in Mone et al., 2011) as having a deep and broad connection with the company that results in the willingness to go above and beyond what is expected to help the company succeed.

Johnson (2011, p. 13) refers to a definition of employee engagement by Towers Perrin as the extra time, brainpower, and the energy that employees put toward their work that result in discretionary effort. They state that employee engagement requires a mutual contract between the organization and its employees, where organizations have a responsibility to train their employees and build a meaningful workplace.

The 2012 Global Workforce study presents a new and more robust definition of employee engagement and focus more on the concept of Sustainable Engagement designed for the 21s,-century workplace. In this regard, sustainable engagement describes the intensity of employees’ connection to their organization based on three core elements (Towerswatson, 2012):

- The extent of employees’ discretionary effort committed to achieving work goals (being engaged);

- An environment that supports productivity in multiple ways (being enabled); and

- A work experience that promotes well-being (feeling energized).

Drawing on the various definitions of employee engagement discussed above, it is apparent that an important thread runs through all the definitions described above, this being the extent of employee discretionary effort to his/her work.

2. Problem statement

Interest in this study revolved around the notable gap that exists regarding a validated model of employee engagement. Popular as the topic may seem, research regarding employee engagement thus far has revealed that there are models supporting the importance of employee engagement, however there remains a shortage of research regarding a practical and theoretical model to measure engagement.

The Corporate Leadership Council’s model of engagement as presented by the Corporate Executive Board (2004, p. 5) defines engagement as the extent to which employees commit to something or someone in their organization, how hard they work, and how long they stay as a result of that commitment and is an outcome-focused model of engagement.

A conceptual model of employee engagement, presented by Shuck et al. (2011, p. 429), reveals that three variables, namely job fit, affective commitment, and psychological climate, are suggested to influence the development of employee engagement.

The research surrounding employee engagement up to now proves informative but has focused mainly on how organizations engage their employees.

To summarize it can be concluded that there is little consideration of what can be done to measure employee engagement and therefore remains a notable gap in literature regarding what organizations can do to measure engagement. This research thus aims to present a validated theoretical model to measure employee engagement in South Africa.

3. Objectives

The aim of this study is to develop a model to measure employee engagement drawing on the commonalities of the various definitions of employee engagement by identifying and examining employee engagement drivers through literature, identifying the measuring criteria of the employee engagement drivers and to present a validated model of employee engagement in South Africa.

The primary objective of this article is to develop a validated and reliable model to measure employee engagement.

The secondary objectives are to:

- develop a theoretical model by identifying employee engagement constructs from the literature;

- identify the measuring criteria of these constructs are identified from the literature

- validate the variables that measure each of the employee engagement constructs;

- assess the sampling adequacy of each of the variables;

- test the applicability of the data for multivariate statistical analysis (such as an exploratory factor analysis);

- determine the importance of each of the employee engagement constructs;

- test the reliability of each of the business success influences in the model; and to

- present an adapted model that can be used to measure employee engagement.

4. Literature review

A total of 11 employee engagement constructs have been identified from the literature study. These constructs are discussed below.

Table 1. Employee engagement constructs

| Construct | Researchers |

1 | Cognitive drivers | Shuck & Reio (2013), Mone & London (2011), Gallup (2011), Brown & Leigh (1996 in Shuck & Reio, 2013, p. 3), Fredrickson (1998; 2001 as cited by Shuck & Reio, 2013, p. 4), Khan (2010 in Shuck & Reio, 2013, p. 4), Collins, (2014), TBS (2011) |

2 | Emotional engagement | Shuck & Reio (2013), Hughes & Rog (2008), Gallup (2011) |

3 | Behavioral engagement | Shuck & Reio (2013), Johnson (2011), Shuck et al. (2011), Parkes (2011), Vamce (2006), Shroeder- Saulnier (2014), Vance (2006) |

4 | Feeling valued and involved | Johnson (2011), Shucketal. (2011), Gallup (2011), Konrad (2006), Robinson etai. (2004) |

5 | Having an engaged leadership team | Johnson (2011), Mone & London (2009), Kanaka (2012), Gallup (2011), Brunone (2013), Hewitt (2013), Crim &Seijts (2006), Mone etai. (2011) |

6 | Trust and integrity | Hughes & Rog (2008), Mone & London (2009), Gallup (2011), Covey (2009), Mone et al. (2011), Schroeder- Saulnier (2010) |

7 | Nature of my job | Hughes & Rog (2008), Kanaka (2012), Gallup (2011), Custominsight (2013) |

8 | The connection between individual and company performance | Hughes & Rog (2008), Kanaka (2012), Mone & London (2009), Gallup (2011) |

9 | Career growth opportunities | Hughes & Rog (2008), Mone & London (2009), Kanaka (2012), Gallup (2011) |

10 | Stress free environment | Kanaka (2012), Aveta Business Institute (2014) |

11 | Change management | Kanaka (2012), (Dicke et al., 2007), Vance (2006) |

4.1. Cognitive drivers. The levels of cognitive engagement originate from an employee’s appraisal of whether their work is meaningful, safe (physically, emotionally, and psychologically), and if they have sufficient levels of resources to complete their work (Shuck & Reio, 2013, p. 4). In this regard, Shuck & Reio (2013, pp. 3-5) lists research (Brown & Leigh, 1996, Fredrickson, 1998; 2001 & Khan, 2010) that suggest that this psychological interpretation of work reflects:

- a level of engagement, or movement, toward their work;

- paralleling the broadening of resources as proposed by; and that

- those who believe their work matters embrace and engage it.

On the other hand, employees who experience negative work circumstances (such as a negative workplace climate or organizational culture) develop a downward spiral of emotions resulting in a narrowing of resources that end in feelings of loneliness, ostracism, and burnout (Shuck and Reio; 2013, p. 5). A negative work environment as highlighted by Murphey (2013) will make all workers feel irritable, anxious and defensive. This can lead to poor productivity, a lack of motivation and morale and poor communication.

To understand what is a negative work environment it is important to understand what is a positive work environment. A positive workplace environment is filled with employees who believe they have a purpose at their jobs, they are making a difference, adding to the growth of the company or simply being a valuable part of the team. A negative environment lacks this feeling - the employees will feel they are performing work that does not serve a purpose. Without a sense of purpose, the motivation to complete responsibilities with pride and enthusiasm is hard to come by. (Murphey 2013, p. 1 in Collins, 2014)

Shuck and Reio (2013, p. 5) reasons that cognitive engagement revolves around how employees appraise their workplace climate, as well as the tasks they are involved in. As an employee makes an appraisal, they determine levels of positive or negative affect, which in turn influences behavior. Their study indicates that cognitively engaged employees would answer positively to questions such as “the work I do makes a contribution to the organization”, “I feel safe at work”, no one will make firn of me here”, and “I have the resources to do my job at the level expected of me”.

In a study conducted by Shuck et al. (2011, p. 427) employee engagement is defined as ‘an individual employee’s cognitive, emotional and behavioral state directed toward desired organizational outcomes’. The study proposed that employees who worked in jobs where the demands of a job were congruent with interests and values (job fit) feel as if they emotionally identify with their place of work and would be more likely to be engaged.

Job fit is defined as the degree to which a person feels their personality and values fit with their current job. Researchers who study job fit suggest that good fit provides opportunities for employees to be involved in individually meaningful work that affects the development of work-related attitudes. Additionally, good fit provides the cognitive stimulus for employees to engage in behavior directed toward positive organizational outcomes. For example, an employee with high levels of job fit might agree that demands of his or her job allow them to work within a level of emotional and physical comfort and that his or her personal values match those of the job role, conceptually resulting in higher performance, discretionary effort and higher levels of job satisfaction (TBS, 2011).

Notwithstanding, employees who experience good fit derive a degree of meaningfulness from their work, resulting in employees who have the emotional and physical resources to complete then- work. Employees who experience job fit within their work roles are more likely to perform their jobs with enthusiasm and energy.

4.2. Emotional engagement. Emotional engagement as identified by Shuck and Reio (2013, p. 5) revolves around the broadening and investment of the emotional resources employees have within their influence. When employees are emotionally engaged with their work, they invest personal resources such as pride, trust, and knowledge. The investment of such resources may seem trivial at first glance; however, consider the work of prideful employees who fully trust their work environment. The positive emotions of pride and trust stem from appraisals made about the environment during the previous stage (such as cognitive engagement, this work is meaningful, it is safe for me here at work, and I have the resources to complete my tasks). Crabb (2011, p. 31) states that the driver ‘Managing emotions’ relates to intrapersonal intelligence: the ability to be self-aware, acknowledge and understand our own thoughts, feelings and emotions. He goes on to say that an individual must be able to fully focus on the tasks that they are undertaking, rather than be distracted by negative or irrelevant thoughts, if they are to develop the right mindset for engagement.

Accordingly, these feelings of positive emotion momentarily broaden an employee’s available resources and enhance critical and creative thinking processes often displayed during moments of engagement. During the emotional engagement process, feelings and beliefs an employee holds influence and direct outward energies toward task completion. Employees who are emotionally engaged in their work answer affirmatively to questions such as “I feel a strong sense of belonging and identity with my organization” and “I am proud to work here.” (Shuck and Reio, 2013, p. 5)

Hughes and Rog (2008, p. 749) conclude that emotional drivers such as one’s relationship with one’s manager and pride in one’s work had four times greater impact on discretionary work effort than did the rational drivers, such as pay and benefits. Ensuring these drivers are present in the organization has profound implications for HRM policies and practices with respect to anyone who is in a supervisory capacity.

As mentioned above, in a study conducted by Shuck et al. (2011, p. 427), it may follow that an employee who has job fit feels emotionally identified with the place of work and would be more likely to be engaged. This is referred to affective commitment.

Affective commitment was defined as a sense of belonging and emotional connection with one’s job, organization, or both (Shuck et al., 2011, p. 430). More than any other type of commitment, affective commitment emphasizes the emotional connection employees have with their work and closely parallels the emotive qualities of engagement, including such conditions as meaningfulness and safety, directly paralleling to seminal work by Kahn’s (1990) conditions of engagement. Such emotive qualities can stimulate employees to willingly engage in behavior directed toward desired organizational outcomes, emphasizing the emotional fulfillment employees experience as a result of being engaged. Emotional fulfillment is an important component of being engaged in work and in indicative of an engaged employee (Shuck et al., 2011, p. 430).

4.3. Behavioral engagement. Shuck and Reio (2013, p. 5) reason that behavioral engagement is the most overt form of the employee engagement process. It is often what we can see someone does. Understood as the physical manifestation of the cognitive and emotional engagement combination, behavioral engagement can be understood as increased levels of effort directed toward organizational goals. Resultantly, behavioral engagement can be described as the broadening of an employee’s available resources displayed overtly.

Related to this is the “intention to turnover” as identified as an organizational outcome associated with the degree of employee engagement from a study conducted by Shuck et al. (2011, p. 431). It is referred to as an employees’ intention to engage in a certain type of behavior, which is a powerful predictor of that employee’s future behavior.

From this context, employee’s effort in the context of engagement is linked to increased individual effort. While engagement occurs one employee at a time and is experienced uniquely through the lens of each employee. Employees who are behaviorally engaged answer positively to questions such as “ When I -work, I really push myself beyond -what is expected of me” and "/ -work harder than is expected to help my organization be successfur (Shuck & Reio; 2013, p. 5).

As noted by Johnson (2011, p. 14) a challenge is that engagement is derived based on how employees feel about their work experiences. Fundamentally, engagement is about whether an employee desires to put forth discretionary effort. Johnson continues and states that engaged employees exhibit the following clear behaviors:

- Belief in the organization - refers to ‘sharing the DNA’ where employees demonstrate an extremely strong belief in the purpose, values and work of the organization (Parkes, 2011, p. 5).

- Desire to improve their work - an engaged employee is willing to put forth discretionary effort in their work in the form of time, brainpower and energy, above and beyond what is considered adequate (Vamce, 2006).

- An understanding of the business strategy - an organization is aligned when all have a commonality of purpose, a shared vision, and an understanding of how their personal roles support the overall strategy (Shroeder-Saulnier, 2014).

- The ability to collaborate with and assist colleagues (Sorenson, 2013, p. 1). In addition, Harter (2013) states that: “If you're engaged, you know what’s expected of you at work, you feel connected to people you work with, and you want to be there” and “You feel a part of something significant, so you’re more likely to want to be part of a solution, to be part of a bigger tribe. All that has positive performance consequences for teams and organizations”.

- The willingness to demonstrate extra effort in their work. An employee’s willingness to engage in discretionary effort, defined as an employee’s willingness to go above minimal job responsibilities, indicates an intention to act that results in behavior. Effort has been linked to productivity and profit generation and is increasingly used as leverage for HRD interventions. Increased effort is widely believed to be a behavioral outcome of engagement (Shuck et al., 201 l,p. 431).

- The drive to continually enhance their skill set and knowledge base - through training you help new and current employees acquire the knowledge and skills they need to perform their jobs. Employees who enhance their skills through training are more likely to engage fully in their work, because they derive a satisfaction from mastering new tasks (Vance, 2006, p. 13).

In summary, it is concluded that engaged employees are those who are willing to put forth discretionary effort in order to ensure the organization is successful.

4.4. Feeling valued and involved. Konrad (2006, p. 1) suggests that high-involvement work practices can develop the positive beliefs and attitudes associated with employee engagement, and that these practices can generate the kinds of discretionary behaviors that lead to enhanced performance. High involvement work practices that provide employees with the power to make workplace decisions, training to build their knowledge and skills in order to make and implement decisions effectively, information about how their actions affect business unit performance, and rewards for their efforts to improve performance, can result in a win-win situation for employees and managers.

IES research suggests that if we accept that engagement, as many believe, is ‘one step up’ from commitment, it is clearly in the organizations interests to understand the drivers of engagement. The strongest driver of all identified in their research is a sense of feeling valued and involved (Robinson et al., 2004, p. 1).

This view is supported by Johnson (2011, p. 15) who states that this driver feeling valued and involved' is the strongest driver and organizations need to understand the voice of the employee and be aware of employees’ needs, issues, and values.

According to Johnson (2011, p. 15) this is the strongest driver. Organizations need to understand the voice of the employee and be aware of employees’ needs, issues, and values. Johnson (2011, p. 15) in support of Robinson et al. (2004, p. 1) identifies several key components, that contribute to feeling valued and involved, including involvement in decision making, ability to voice idea. Managers listen to these views and value employees’ contributions, opportunities employees have to develop their jobs, and the extent to which the organization demonstrates care for its employees’ health and well-being.

The line manager clearly has a very important role in fostering employees’ sense of involvement and value - an observation that is completely consistent with IES research (Robinson et al., 2004, p. 1).

4.5. Engaged leadership team. Effective leadership is Having leaders who can help cascade the vision and inspire others to exceptional performance is an equally important part of making engagement flourish in your team, your department, and your company (Brunone, 2013, p. 1).

Hewitt’s (2011) analysis of companies with strong financial results shows that one distinguishing feature is the quality of their senior management. In particular, we see that senior managers’ levels of engagement are high and their ability to engage others in the organization, particularly those in middle management, is strong. And it does not stop there: engaged managers are more likely to build engaged teams. In short, engagement starts at top, and without engaged senior leadership, companies will not be able to engage the hearts and minds of their employees.

With respect to leadership communication it is important to be frequent and forthright, answering the questions employees are asking. Even if the response is “We don’t know”, employees appreciate that their concerns are being heard. Apart from communication as an important element in building the perception of leader effectiveness there are other leadership behaviors that influence employee engagement. Leaders must show that they value employees. Employee-focused initiatives such as profit sharing and implementing work-life balance initiatives are important. Employee engagement is a direct reflection of how employees feel about then- relationship with the boss. Employees look at whether organizations and their leader walk the talk when they proclaim that, “Our employees are our most valuable asset” (Crim & Seijts, 2006, p. 1). This means that leaders:

- Come across as more connected with employees meaning that they:

- Effectively communicate the organization’s goals and objectives;

- Consistently demonstrate the organization’s values in all behaviors and actions;

- Appropriately balance employee interests with those of the organization; and

- Fill employees with excitement for the future of the organization.

- Are performance focused that entails:

- Effectively communicate the organization’s goals and objectives;

- Empower managers and employees and instill a culture of accountability; and

- Set aggressive goals at all levels of the organization.

- Are future and development oriented and focus to:

- Communicate the importance of spending time on feedback and provide performance coaching;

- Fill employees with excitement about the future of the organization;

- Effectively communicate the skills/capa-bilities employees must develop for future success; and

- Invest in long-term growth opportunities, even during difficult times.

Mone et al. (2011, p. 207) state that managers drive engagement when they provide ongoing feedback and recognition to direct and improve performance and have career-planning discussions with their employees. This supports the theory leadership behaviors identified by (Crim & Seijts, 2006, p. 1) but adds that the leaders additionally influence employee engagement.

While managers play a role in the day-to-day work experience of their direct reports, the importance of effective senior leadership on employee engagement cannot be underestimated. When senior leaders are themselves engaged, they are more likely to positively affect the engagement of other staff. When these senior leaders communicate frequently and honestly, clearly charting the course for the organization and letting employees know what is required of them to help make the business successful, employee engagement increases. And when leaders actively endorse initiatives that drive engagement, the effect is multiplied.

Employees also will stay longer and contribute more to organizations where they have good relationships and open dialogue with their immediate supervisors (Johnson, 2011, p. 5).

4.6. Trust and integrity. The first job of any leader is to inspire trust. Trust is confidence bom of two dimensions: character and competence. Character includes your integrity, motive, and intent with people (Covey, 2009, p. 1). Hughes and Rog (2006, p. 749) define trust and integrity as the extent to which the organization’s leadership is perceived to care about employees, listens and responds to their opinions, is trustworthy, and “walks the talk”. Mone et al. (2011) found that having a manager employees can trust is a primary driver of engagement.

According to Schroeder-Saulnier (2010, p. 3) building trust through effective communications is absolutely essential. Employees need to trust that their leaders have the capability to make the organization successful. To win that trust, leaders must show that they have a plan, articulate that plan clearly to employees, and demonstrate that that plan is being implemented effectively. Trust is a two-way street. Leaders must also show that they, in turn, trust employees to help drive organizational success. They must make employees valued partners in a common enterprise. Employees want not only to know what the bigger picture is, but also to feel that they are a part of that picture.

4.7. Nature of my job. This driver, “nature of my job” according to Hughes and Rog (2008, p. 749) is defined as the extent of employee participation and autonomy. Encouraging employee accountability is key thing. (Kanaka, 2012, p. 65). Advocating the thought of accountability ensures that people are trusted with a job, the responsibility that comes with the job and are expected to complete the job in stipulated time intervals.

Research from custom insight (Custominsight, 2013) indicates that the way to drive engagement to the highest levels, is by empowering employees and by making sure that all employees are held accountable for achieving results. Moreover, these areas are important for attracting, retaining, and motivating the most talented employees. People who value empowerment and accountability will be discouraged in companies that do not promote and support these things. By contrast, poor performers might enjoy the safe haven of a company that does not demand accountability. These are employees who might have high levels of “satisfaction”, but they are likely to be adding little or no value, and even worse, discouraging the talented people around them.

Kanaka (2012, p. 65) goes on to say that encouraging employee participation by encouraging employees to participate in decision making and other organizational tasks is an important facet every organization needs to build. Employee participation ensures a high degree of connectivity to the organization and this connectivity is employee engagement.

4.8. Connection between individual and company performance. The engagement driver “Connection between individual and company performance” is the extent to which employees understand the company’s objectives, current levels of performance, and how best to contribute to them. (Hughes & Rog, 2008, p. 749). Goal setting, of course, is a critical component of performance management and research from Mone and London (2009), who suggest that when managers and employees set goals collaboratively, employees become more engaged.

Kanaka (2012, p. 65) states that top management needs to allow free flow of information, such as industry updates, sectoral updates, quality issues, and compliances, and employee development updates to ensure that employee engagement is a driver of success.

Gallup’s research (2011, p. 3) shows that many great work places have defined the right outcomes; they set goals for their work groups or work with them to set their own goals. They do not just define the job but define success on the job.

Gallup’s (2011, pp. 3-4) research also indicates that effective workplaces provide constant clarification of the overall mission of the organization, as well as the ways in which each individual team member contributes to the achievement of the mission. As human beings we like to feel as though we belong. Individual achievement is great, but we are likely to stay committed longer if we feel we are part of something bigger than ourselves.

Research by Crabb (2011, p. 32) refers to how well the individual’s values align to the work that they do and the values and the culture of the organization. This is referred to as “Aligning Purpose”.

It may be concluded that where employee’s values are aligned to the organization’s values, individual and organizational benefits are achieved that will ultimately lead to enhanced business performance, employee commitment and a competitive advantage for the organization.

4.9. Career growth opportunities. Career Growth Opportunities refer to the extent to which employees have opportunities for career growth and promotion or have a clearly defined career path (Hughes & Rog, 2008, p. 749). In keeping with this definition, Mone and London (2009) also found that a director predictor of employee engagement is the extent to which employees are satisfied with their opportunities for career progression and promotion suggesting that employees will feel more engaged if managers provide challenging and meaningful work with opportunities for career advancement. Their research also found that when managers provide sufficient opportunities for training and support regarding career development efforts, they help foster employee development and drive employee engagement.

Gallup (2011, p. 14) also indicates that great workplaces are those in which work groups are provided with educational opportunities that address their development which may include formal classes or simply finding new experiences for them to take on. This research also defines “opportunities” as training classes and seminars for some and for others this might mean promotions and increased responsibilities whilst for others this might mean working on special projects and assignments.

4.10. Stress-free environment. A stress free environment as identified by Kanaka (2012, p. 65) means that employees put their best efforts (see section 4.3) they can innovate and be creative ensuring optimum output. Most people have found out that when they work in a firn and relaxing atmosphere, they can be more relaxed which means they can be more successful. They can share their personal ideas and experiences and in a healthy working environment, it should be encouraged. All employees should feel valued and appreciated. You can start fun team-building experiences to get things started. Commitment and involvement are also very important factors that contribute to the success factors of businesses and engagement within the workplace. Lots of research studies have proved that people will stay with a company longer if they feel involved and needed. No one wants to work in a stressful and rude environment. Everyone’s opinions should be listened to and considered by others. This will lead to a decreased rate of employee turnover, which is definitely a goal for any business (Aveta Business Institute, 2014).

Everyone expects a stress free environment at workplace and tends to leave only when there are constant disputes. No one likes to carry tensions back home. An engaged employee does not get time to participate in unproductive tasks instead finishes his assignments on time and benefits the organization.

4.11. Change management. As stated in a white paper on Employee engagement and change management (Dicke et al., 2007, p. 50) “The greater an employee’s engagement, the more likely he or she is to ‘go the extra mile’ and deliver excellent on-the- job performance.” Therefore, if employees are engaged during a change management initiative they are likely to have increased “buy-in” and better performance thus, supporting business success. The Paper goes on to state that employee engagement is listed as a primary function to the success of properly implementing a change management initiative and due to employee engagement’s close relationship to organizational commitment, understanding organizational commitment’s relationship to change management may provide some valuable insight.

Vance (2006, p. 1) indicates that employees who are engaged in their work and committed to then- organizations give companies crucial competitive advantages - including higher productivity and lower employee turnover. Thus, it is not surprising that organizations of all sizes and types have invested substantially in policies and practices that foster engagement and commitment in their workforces.

Dramatic changes in the global economy over the past 25 years have had significant implications for commitment and reciprocity between employers and employees - and thus for employee engagement. For example, increasing global competition, scarce and costly resources, high labor costs, consumer demands for ever-higher quality and investor pressures for greater returns on equity have prompted organizations to restructure themselves. At some companies, restructuring means reductions in staff and in layers of management.

This then relates to the white paper (Dicke et al., 2007, p. 50) which stated that if employees are engaged during a change management initiative they are likely to have increased “buy-in” and better performance thus, supporting business success.”

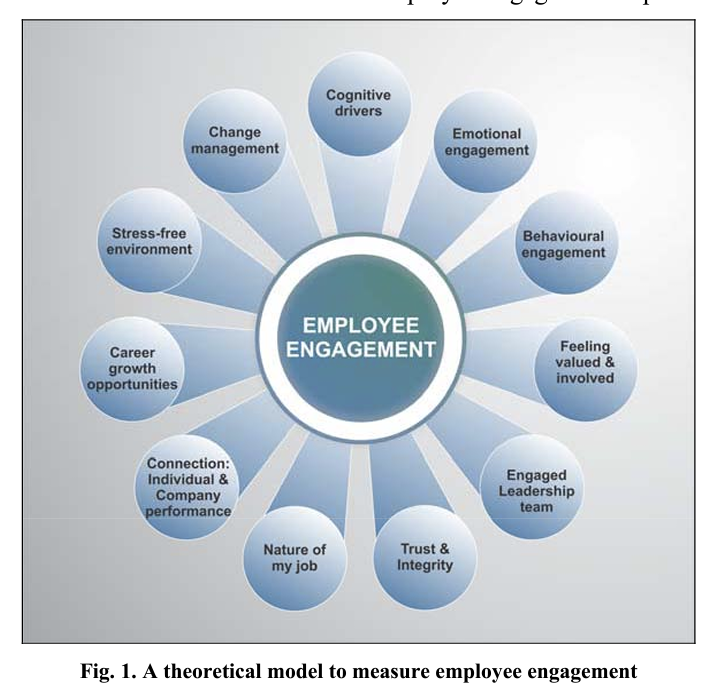

4.12. Theoretical model of employee engagement.

Based on the theoretical study and the identified constructs (as per Table 1) the theoretical model of employee engagement is presented in Figure 1.

5. Research methodology

5.1. Sampling procedure. The sample for this study was drawn from two fully accredited private business schools in KwaZulu-Natal and consists of employees or managers in the databases of these institutions and was restricted to 300 respondents. More specifically, the population consists of part- time students enrolled on a Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree or post-graduate business courses. The students are in full time employment. The rationale behind the selection of this sample is the high exposure of the respondent at a managerial level. Since MBA students may be viewed as the future leaders of the economy of our country their perceptions may be deemed very influential and informed due to their strong work experience and educational background.

5.2. Questionnaire development. A questionnaire were developed from the literature study and selected employees to indicate the importance of the 11 employee engagement constructs by answering 94 measuring criteria in relation to MI and business success. The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale to indicate the perceptions of the respondents’ employee engagement. Although the 11 constructs depict specific components of employee engagement, the synergetic effect when they are interpreted together, provides a coherent picture.

5.3. Data collection. The data collected for this study was through a survey which according to Shajahan (2009, p. 45) is the method of collecting information by asking a set of formulated questions in a predetermined sequence in a structured questionnaire to a sample of individuals drawn so as to be representative of a defined population.

A total of ZOO questionnaires were administered independently by the researcher to respondents for completion at the beginning of MBA workshops at Business Schools in KwaZulu-Natal. In order to ensure a high response rate, respondents were requested to complete the questionnaire at the beginning of the workshops where the researcher herself explained the importance and relevance of the study before waiting for questionnaires to be completed. A total of 260 questionnaires were completed and 18 questionnaires were incomplete resulting in a non-response of 22 questionnaires. This resulted in a total response rate of 86.6%.

5.4. Data analysis. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Incorporated (SPSS) Version 22 was used to analyze the data statistically. Similar research by Chummun (2012) successfully employed the following statistical procedures and decision criteria:

- Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Due to its exploratory nature, factor loadings of 0.4 and higher were considered to validate the items that measure each of the Mi’s business success influences (Field, 2007, p. 668) (Objective 3).

- The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was utilized to ensure that the sample used is adequate. Field (2007, p. 735) suggests that a KMO value of 0.6 should be the minimum acceptable value if exploratory factor analysis is considered (Matlab, 2010 in Chummun, 2012). These values are regarded to be mediocre, while more favorable values are between 0.7 and 0.8. Values between 0.8 and 0.9 are very favorable while ultimately, values above 0.9 are superb) (Objective 4).

- Bartlett’s test of sphericity was used to determine if the data are suitable to employ multivariate statistical analysis. This study follows advice by Field (2007, p. 724) and sets a maximum value of 0.005. Values below 0.005 signify that the data are indeed suitable for multivariate statistical analysis, in this case exploratory factor analysis (Objective 5).

- The variance explained by the factor analysis serves as indicator to determine the importance of each of the constructs to measure employee engagement (Objective 6). Field (2007) indicated that a variance of 60% and higher is regarded to be a good fit to the data. This study aims to achieve a good fit to the data, thus aiming to achieve 60% of variance per factor.

- The reliability of the employee engagement constructs is measured with the Cronbach alpha coefficient. Satisfactory reliability coefficients exceed 0.70 (Field 2007, p. 668). However, a secondary lower reliability coefficient was set at 0.58 because, according to Cortina (1993) in Field (2007, p. 668) confirmed in his research that when ratio and interval scales are used (such as the Likert scale used in this questionnaire) it does warrant a lower reliability coefficient (Objective 7).

5.5. Statistical validation. Each employee engagement construct is validated by calculating the KMO values, Bartlett’s tests of shericity, the variance explained by the specific construct in the factor analysis and the reliability of the specific construct. In addition, measuring criteria with factor loadings below 0.40 are omitted from the analysis while strong dual loading criteria are also omitted because of their dualistic nature (Fields, 2013). This method also determined if all the measuring criteria loads as one factor, meaning that the criteria measure the specific construct as one construct. In cases where more than one factors is identified, the sub-factors are identified and labelled as individual sub-factors of the specific employee engagement construct (Fields, 2013).

6. Results

The results pertaining to each of the employee engagement constructs are discussed below. The statistical results are summarized in Table 2.

6.1. Cognitive drivers. Only one factor was identified by the factor analysis. The analysis further showed that Question 3 (No one will make fun of me) does not contribute to measuring the construct because it has a low factor loading (Below 0.40). As a result, this question was omitted from the analysis. All the other questions loaded onto the factor, signifying their validity in measuring this factor. The KMO and Bartlett test returned favorable values while the variance explained is satisfactory at 64.2%. The factor has a satisfactory reliability coefficient of 0.80.

Table 2. KMO, Bartlett’s test, reliability and variance explained

Construct | Sub-construct | KMO | Bartlett | Cronbach alpha | Var. expl. |

Cognitive drivers | *** | 0.794 | 0.000 | 0.838 | 64.2% |

Emotional engagement | *** | 0.926 | 0.000 | 0.944 | 67.1% |

Behavioral engagement | Employee perceptions Employer perceptions | 0.900 | 0.000 | 0.910 0.373 | 44.4% 20.7% |

Feeling valued and involved | *** | 0.857 | 0.000 | 0.880 | 63.6% |

Having an engaged leadership team | *** | 0.951 | 0.000 | 0.966 | 71.1% |

Trust and Integrity | *** | 0.937 | 0.000 | 0.953 | 76.1% |

Nature of my job | Employment enablers Managerial influences | 0.845 | 0.000 | 0.846 0.823 | 34.5% 34.4% |

Connection between individual and company performance | *** | 0.878 | 0.000 | 0.926 | 66.3% |

Career growth opportunities | *** | 0.936 | 0.000 | 0.949 | 71.4% |

Stress-free environment | *** | 0.814 | 0.000 | 0.944 | 81.2% |

Change management | *** | 0.880 | 0.000 | 0.960 | 71.3% |

Note: * Unreliable (a < 0.70); *** No sub-factors identified.

6.2. Emotional engagement. The analysis of the construct dealing with emotional engagement showed that two statements could be omitted from the analysis since they both had low factor loadings (below 0.40). These questions were 11 (I take pride in my work) and 14 (I have the best friend at work). All the remaining questions loaded onto the factor, signifying their validity in measuring this factor. The KMO and Bartlett test showed very satisfactory values, and the factor explained a high 67% of the variance. In addition, the factor is deemed very reliable with an alpha coefficient of 0.944.

6.3. Behavioral engagement. The construct behavioral engagement consists of two sub-factors. The analysis revealed that none of the questions could be omitted from the analysis. The two subconstructs are Employee perceptions (explain 44.4% of the variance) and Employer perceptions (explaining 20.7% of the variance). However, it is noteworthy that Employer perceptions is not a reliable factor (a = 0.373). The KMO and Bartlett test returned very acceptable values. None of the questions were discarded because they all loaded onto the two sub-factors, signifying their validity in measuring these factors.

6.4. Feeling valued and involved. All items for the construct Feeling valued and involved loaded under one construct, which explained 63% of the overall variance. The KMO test returned an excellent value above 0.8 thereby indicating the sample is adequate. The Bartlett test supported the selection of factor analysis as analytical tool. This factor is regarded to be reliable with an alpha coefficient of 0.880. The analysis shows that one factor is prevalent, and that all the questions are valid in measuring this factor.

6.5. Engaged leadership team. The factor analysis revealed a single factor labeled Engaged leadership team. The KMO and Bartlett tests returned satisfactory values whilst it is worth noting the factor is deemed to be reliable with an alpha coefficient of 0.880. This factor explains variance of 63.6%. All the questions loaded onto the factor, signifying their validity in measuring this factor.

6.6. Trust and integrity. Only one factor was identified by the factor analysis. The factor is labeled Trust and integrity. Favorable values were returned from the KMO and Bartlett tests, indicating the sample was adequate and data was suitable to be employed in multivariate statistical analysis. The factor explained a high variance of 76.1%. In addition, the factor also returned a high Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.937, signifying high reliability. All the questions loaded onto the factor, signifying their validity in measuring this factor.

6.7. Nature of my job. Similar to the construct Behavioral engagement, the construct Nature of my job consists of two sub-factors namely Employment enablers and Managerial influences. The sub-factor Employment enablers explain 34.5% of the variance and the sub-factor Managerial influences explain 34.4% of the variance, signifying that they are both of equal importance to explain the construct Nature of my job. Both sub-constructs are also deemed reliable with Cronbach alpha coefficients of 0.846 and 0.823 for Employment enablers and Managerial influences, Both the KMO and Bartlett tests returned acceptable values. All the questions loaded onto either one of the factors, signifying their validity in measuring these factors.

6.8. Connection between individual and company performance. One factor was extracted for the construct Connection between individual and company performance. The variance explained is 66.3%, and the factor has a high reliability coefficient of 0.926. The KMO test returned an excellent value of 0.878 while the Bartlett test revealed the data is indeed suitable for multivariate statistical analysis. All the questions loaded onto the factor, signifying their validity in measuring this factor.

6.9. Carer growth opportunities. All the questions loaded onto the construct Career growth opportunities, signifying their validity in measuring this factor. The factor explained a variance of 71.4%, indicating a good fit to the data (Field, 2007). The KMO test revealed an excellent value of 0.936 indicating superb sample adequacy, while the Bartlett test was significant indicating data was is suitable to perform a factor analysis. The reliability of the factor is excellent with a coefficient of 0.949.

6.10. Stress-free environment. The construct Stress- free environment revealed only one factor. All the questions loaded onto the factor, signifying their validity in measuring this factor. The favorable KMO value of 0.814 indicated an adequate sample while the Bartlett test was also suitably below the required 0.005. The factor explains a variance of 81.2% which is regarded to be a very good fit to the data (Field, 2007). This factor is deemed very reliable with an alpha coefficient of 0.960.

6.11. Change management. The construct Change management explained a variance of 71.3%. It also displays a very high reliability with an alpha coefficient of 0.960. Both the KMO and Bartlett tests revealed favorable results, and all the questions loaded onto the factor. Resultantly, these questions are deemed valid in measuring this factor.

6.12. Discarded measuring criteria. The statistical process to validate the theoretical model identified a total of three questions in the questionnaire that could be omitted from the analysis. These questions did not load onto a specific factor and had low factor loadings (below the required 0.40 factor loading set in this study). These non-relevant criteria are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Deleted measuring criteria (questions) in questionnaire

No. | Measuring Criteria |

3 | No one will make fun of me |

11 | I take pride in my work |

14 | I have a best friend at work |

7. Validated model of employee engagement

Figure 2 shows the validated model to measure employee engagement. The statistical analysis to validate the theoretical model shows that the original theoretical model (see Figure 1) contains more than just 11 constructs to measure employee engagement. It also contains sub-constructs that pertain to some of the constructs. These constructs and sub-constructs are shown in Figure 2. The reliability of the constructs and sub-constructs were also determined. Some of sub-actors did not yielded unsatisfactory Cronbach Alpha coefficients, meaning that they are not reliable. In this regard Du Plessis (2010) points out that these sub-constructs with lower reliability coefficients are less likely to present themselves in a repetitive study. Only one sub-construct (Employer perceptions; Cronbach Alpha = 0.373) falls into the low reliability category should therefore be interpreted bearing this constraint in mind (see Figure 2 in Appendix).

Conclusions

The following conclusions are made from this study:

- The factors returned high cumulative variances in excess of 60% which is regarded to be good fit of the data (Chummun, 2012; Shukia, 2004).

- The reliability of the data employed in this measuring instrument is high (exceeding 0.80 with ease) for all the factors. Only one subfactor (Employer perceptions) has low reliability (0.373). This sets the scene to continue with the validation of the questionnaire.

- Both the Bartlett test of Sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy returned high values signifying that the sample was adequate and that the data were suitable to perform factor analyses.

- The questionnaire used is a valid research tool and suitable to be used to measure employee engagement in South Africa.

Summary

The primary objective of this study was to develop a theoretical model and to validate this model statistically to measure employee engagement amongst managers in South Africa (see Figure 2). The study set eight secondary objectives to achieve the primary objective. All of them were reached. This means that the model also resulted in a validated questionnaire to measure employee engagement. The questionnaire was tested and ensured that it is valid for use. The study can, therefore, continue to measure the employee engagement of the managers and thereafter make recommendations to positively influence employee engagement as managerial tool in business success.

References

- Aveta Business Institute (2014). Six Sigma certification. Accessed at: sixsigmaonline.org. Date of access: 14 June 2014.

- Brunone, C. (2013). Leadership Development vs. Employee Engagement. Accessed at: http://www.blessingwhite.com/content/articles/enews/June2013.asp?pid=2. Date of access: 10 May 2013.

- Chummun, B.Z. (2012). Evaluating business success in the Microinsurance industry of South Africa. (Thesis - PhD) Potchefstroom: North-West University).

- Collins, M. (2014). Recruitment & HR Services Group. Accessed at: collinsmnicholas.ie/blog/?p=660. Date of access: 10 May 2013

- Covey, S.M.R. (2009). How the Best leaders Build Trust. Chicago: Linkage’s Eleventh Annual Best of Organization Development Summit. Accessed at: http://www.leadershipnow.com/CoveyOnTrust.html. Date of access: 17 June 2014.

- Crabb, S. (2011). The use of coaching principles to foster employee engagement, The Coaching Psychologist, 7 (l),pp. 27-34.

- Crim, D. & Seijts, G. (2006). What engages employees the most or, the ten Cs of employee engagement, Ivey Business Journal, Available at: http://iveybusinessjournal.com/topics/the-workplace/what-engages-employeesthe-most-or-the-ten-cs-of-employee-engagement. Date of access: 17 June 2014.

- Custominsight (2013). What Drives the Most Engaged Employees? Accessed at: http://www.custominsight.com/employee-engagement-survey/research-employee-engagement.asp, date of access: 14 June 2014.

- Dicke, C., Holwerda, J. & Kontakos, A.M. (2007). Employee Engagement. What do we really know? What do we need to know to take Action? Paris: CAHRS. Available at: http://www.uq.edu.au/vietnampdss/docs/July2011/ EmployeeEngagementFinal.pdf. Date of access: 17 June 2014.

- Du Plessis, J.L. (2010). NWUStatistical Consultation Services, Potchefstroom, North-West University.

- Field, A. (2007). Discovering statistics using SPSS, 3rd ed., London, Sage.

- Fields, Z. (2013). A conceptual framework to measure creativity at tertiary educational level. (Thesis - PhD) Potchefstroom: North-West University).

- Gallup (2011). Employee Engagement: What’s your employee ratio? Washington, Gallup.

- Harter, J. (2013). Chief scientist of workplace management and wellbeing, Washington, Gallup.

- Hewitt, A.O.N. (2011). The multiplier effect: Insights into how senior leaders drive employee engagement higher. Accessed at: http://www.aon.com/attachments/thought-leadership/Aon-Hewitt-White-paper_Engagement.pdf

- Hughes, J.C. & Rog, E. (2008). Talent Management: A strategy for improving employee recruitment, retention and engagement within hospitality organisations, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20 (7), pp. 743-757.

- Johnson, M. (2011). Workforce Deviance and the Business Case for Employee Engagement, Journal for Quality & Participation, 34 (2), pp. 11-16.

- Kanaka, M.L.G. (2012). Employee Engagement: A corporate boon, 10 ways for effective engagement, Advances in Management, 5 (2), pp. 64-65.

- Konrad, A.M. (2006). Engaging employees through high-involvement work practices, Ivey Business Journal, Accessed at: http://iveybusinessjournal.com/topics/the-workplace/engaging-employees-through-high-involvementwork-practices. Date of access: 17 June 2014.

- Mone, E., Eisinger, C., Guggenheim, K., Price, B. & Stine, C. (2011). Performance Management at the Wheel: Driving Employee Engagement in Organisations, Journal of Business and Psychology, 26 (2), pp. 205-212.

- Parkes, L. (2011). Employee engagement. Igniting Passion through purpose, participation and progress. (In: California State University. Accessed at: http://www.fullerton.edu/cice/Documents/2013CEReport.pdf. Date of Access: 1 Sep 2014).

- Robinson, D., Perryman, S. & Hayday, S. (2004). The drivers of employee engagement, London: Institute for employment studies. Accessed at: http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/pubs/summary.php7idM08. Date of access: 17 June 2014.

- Shroeder-Saulnier, D. (2010). Employee engagement: Drive organisational effectiveness by building trust. Right Management: A manpower company. Accessed at: http://www.right.com/ thought-leadership/e-newsletter/drive- organizational-effectiveness-by-building-trust.pdf. Date of access: 17 June 2014.

- Shuck, B. & Reio, G. (2013). Employee Engagement and well-being: A moderation model and implications for practice, Journal of Leadership and Organisational Studies, 21 (1), pp. 43-58.

- Shuck, B., Reio, G. & Rocco, S. (2011). Employee engagement: an examination of antecedent and outcome variables, Human Resource Development International, 14 (4), pp. 427-445.

- Shukia, P. (2004). T-Test and Factor analysis, University of Brighton. Accessed at: http://www.pauravshukla.com/marketing/research-methods/t-test-factor-analysis.pdf. Date of access: 20 April 2011.

- Sorenson, S. (2013). Dont Pamper employees-engage them. Accessed at: http://business-journal.gallup.com/content/163316/don-pamper-employees-engage.aspx. Date of access: 17 June 2014

- TBS (2011). 2011 Public service employee survey: Focus on employee engagement. Accessed at: http://www.tbssct.gc.ca/pses-saff/2011/engage-mobil-eng.asp Date of access: 10 June 2013.

- Thayer, S.E. (2008). Psychological climate and its relationship to employee engagement and organisational citizenship behaviours. Accessed at: http://www.academia.edu/6709919/Employee_Engagement_and_Organizational_Effectiveness_The_Role_of_Organizational_Citizenship_Behavior.

- The Corporate Executive Board (2004). Driving performance and retention through employee engagement, New York: The Corporate Leadership Council.

- Towerswatson (2012). Global Workforce Study: Engagement at risk: driving strong performance in a volatile global environment. Accessed at: http://www.towerswatson.com/Insights/IC-Types/Survey-Research-Results/ 2012/07/2012-Towers-Watson-Global-Workforce-Study Date of access: 10 May 2013.

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat See TBS.

- Vance, R.J. (2006). Employee Engagement and Commitment. New York: SHRM Foundation. Accessed at: http://www.vancerenz.com/researchimplementation/uploads/1006employeeengagementonlinereport.pdf. Date of access: 12 June 2014.