The impact of key audit matter (KAM) disclosure in audit reports on stakeholders’ reactions: a literature review

Published: Oct. 4, 2019

Latest article update: Dec. 12, 2022

Abstract

This article presents a literature review of 49 empirical studies on key audit matter (KAM) disclosure in audit reports. The study involves a structured literature review on KAM disclosure based on the reactions of stakeholders. The limitations of former studies and useful recommendations for research are stressed. Five major streams of empirical research that analyze the impact of KAM disclosure on stakeholders’ reactions are focused: (1) shareholders (e.g. investors’ perceptions of auditors’ responsibility and litigation, value relevance and investors’ decisions); (2) debtholders (e.g. loan contracting terms); (3) external auditors (e.g. audit processes and audit fees); (4) boards of directors (e.g. earnings management); and (5) other stakeholders (e.g. informational value for suppliers and customers). The authors stress that most of the included studies use experimental or archival data and analyze the impact of KAM disclosure on investor reactions in a US-American setting. As the international standard setters assume a positive impact of KAM on stakeholder reactions, mixed empirical results are found. Although there are some indications of decreased earnings management behavior, most studies find no significant changes in auditor behavior. Furthermore, there are many insignificant results with regard to shareholders’ reaction in line with our stakeholder and behavioral agency framework. The literature review is especially useful for management decisions, because firm reputation may be positively or negatively influenced by KAM regulations

Keywords

Earnings Management, critical audit matters, audit quality, stakeholder agency theory, key audit matters

INTRODUCTION

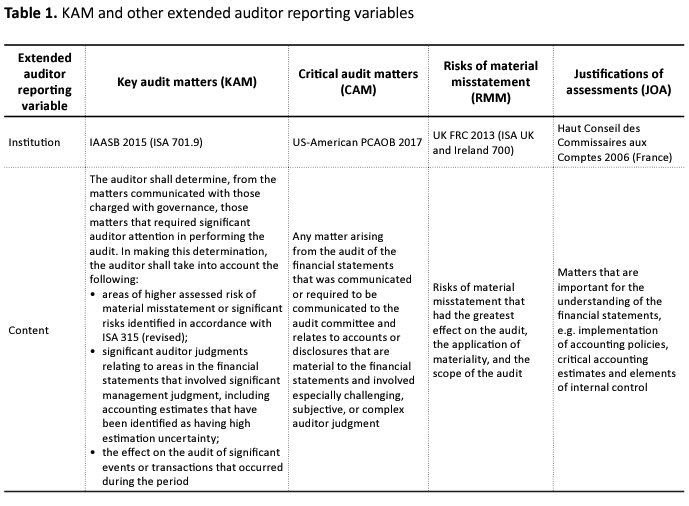

After the 2008-2009 financial crisis, stakeholders widely criticized public interest entities’ (PTEs’) financial reporting and external auditors’ reporting. Longer and more complex annual and audit reports are associated with a high risk of information overload and impaired usefulness for decision-making regarding the capital market (Bedard et al., 2016; Gimbar et al., 2016). In particular, private investors and other kinds of unsophisticated stakeholder groups find it difficult to extract relevant information for their financial analyses. Information asymmetries and conflicts of interest among the board of directors, auditors, share- and debtholders and other stakeholders lead to an expectation gap (Bedard et al., 2016; Gold et al., 2012). In reaction to the huge concern among stakeholders, many regulators introduced extended auditor reporting (see Table 1) for PIEs in recent years. Reduced information asymmetry, increased financial reporting and audit quality and increased value relevance of audit reports are the main goals of audit reporting regulations. In France, justifications of assessments (JOA) have been required since 2003 (Haut Conseil des Commissaires aux Comptes, 2006). Moreover, the UK Financial Reporting Council (FRC) implemented new disclosure rules regarding the significant risks of material misstatement (RMM) in the audit reports of companies with premium listings of equity shares on the main market of the London Stock Exchange (LSE) since the fiscal year beginning on 1 October 2012 (FRC, 2013). In 2015, the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB), as the international audit standard-setter, implemented key audit matters (KAM) for business years after December 14, 2016 (IAASB, 2015). Finally in 2017, the US-American Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) introduced the disclosure of critical audit matters (CAM) (PCAOB, 2017). Table 1 presents the four main types of extended auditor reporting. Considering the notable interdependency between the four items, the low amount of JOA and RMM studies, the recent change from RMM and JOA to KAM in the UK and France and the many researchers who use the term KAM, we favor KAM in our literature review. If there are specific differences between CAM/KAM, RMM and JOA in our research results, we will explain them in detail. Otherwise we will only use the term KAM in our analysis.

In comparison to recent literature reviews on extended auditor reporting (e.g. Gimbar et al., 2016; Bedard et al., 2016), we chose a different review strategy and identified five major streams of empirical research that analyze the impact of KAM disclosure on stakeholders’ reactions. Most of the 49 empirical studies concentrate on the influence of KAM on (1) shareholders (e.g. investors’ perceptions of auditor responsibility and litigation, value relevance and investors’ decisions) and found mixed results. The same applies for (2) debtholders as another relevant stakeholder group, but very few studies have been conducted on it so far. KAM disclosure should also have an impact on (3) external auditors’ behavior (e.g. audit processes and audit fees). But most of the empirical research does not find any significant results. While KAM disclosures in the audit report mainly addressed external stakeholders, another stream of research analyses the impact of KAM disclosure on (4) the board of directors. Most of the included studies find а negative impact on earnings management as assumed. Finally, some studies also include (5) other stakeholders, typically based on stakeholders’ broad comments on regulations, and state an increased informational value of KAM disclosure.

Our structured literature review contains useful recommendations for future research and is also relevant for regulators and practice. Based on the five streams of research, we identify whether the goals of the regulators have been achieved. We also determine how different stakeholders are integrated into recent research activities. After providing a foundation on stakeholder and behavioral agency theory, we highlight the main results of empirical KAM research on different stakeholder groups, explain the studies’ key limitations and give useful recommendations for future research. Finally, we provide a summary of the main results. The results of our literature review are especially relevant for management strategies (e.g. earnings management, management reporting) as extended auditor reporting can mainly influence stakeholder reaction and thus firm reputation.

1. AGENCY THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

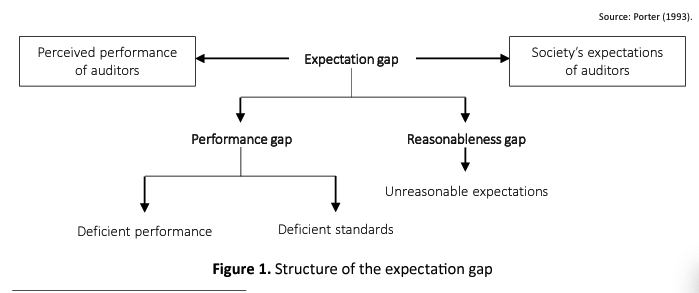

According to stakeholder agency theory, an external auditor acts as an agent for shareholders and other stakeholders (Hill & Jones, 1992; Ross, 1973; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Chow, 1982). External audits are intended to increase stakeholders’ trust in financial statements. The auditor serves as a gatekeeper or public watchdog for the stakeholders (Kraakman, 1986). Publication of the audit report with KAM disclosures should ensure appropriate audit quality1 and financial reporting quality2 in line with stakeholders’ interests (Ittonen, 2012). Empirical audit research has proved that audit reports can significantly influence capital market reactions (Bedard et al., 2016; Gimbar et al., 2016). As audit quality cannot be observed by stakeholders, the audit report is a key information tool. However, the informational value of the audit report and related market reactions are mainly affected by the expectation gap phenomenon due to agency conflicts (Liggio, 1974). The expectation gap represents the difference between stakeholders’ assumptions concerning the purpose and range of the audit and the real audit. According to the famous approach proposed by Porter (1993), the expectation gap can be divided into a performance gap and a reasonableness gap (see Figure 1).

Prior research states that financial statement users often expect an absolute and not a reasonable level of external audits, and a guarantee of the absence of fraud or financial distress (Gold et al., 2012), resulting in the reasonableness gap. This gap occurs when stakeholders lack knowledge about the audit risk model of the external auditor. Audit risk can be separated into inherent risk, control risk and detection risk. Audit risk is the risk of submitting an unqualified audit opinion with substantial errors in the financial reporting. Inherent risks (e.g. business risk) and control risks (e.g. an insufficient internal control system) cannot be influenced by the external auditor himself; he can only influence detection risk, as he may choose between different kinds of audit proof. A key goal of external audits is to lower audit risk to an appropriate level (5% on average) with reference to materiality and efficiency. KAM disclosure can lower the reasonableness gap as the stakeholders can be better informed about the range and limits of external audits (Veite, 2018). The performance gap, the second part of expectation gap, can be linked to deficient performance and standards (Porter, 1993; see Figure 1). International regulations on KAM disclosure indicate that prior auditor reporting standards were not decision-useful for stakeholders as they did not get firm-specific information about the audit process and the outcome (Bedard et al., 2016). Furthermore, as external auditors are also economic agents, a lower degree of auditor reporting can lead to decreased performance and quality incentives. Thus, KAM disclosure may decrease all main sources of the expectation gap in line with regulators’ assumptions (FRC, 2013; IAASB, 2015; PCAOB, 2017).

Empirical research on the expectation gap can be separated into three major streams (Gold et al., 2012). One stream focuses on the existence of the expectation gap in several countries. The second stream analyzes the influence of stakeholders’ sophistication (i.e. level of experience and knowledge) regarding financial reporting and auditing on the expectation gap. In contrast to professional investors, private investors and other stakeholders with lower knowledge are more dependent on audit reports (Porter, 1993). The third research stream relates to the impact of differences in wording in the audit report on the expectation gap. Prior research stresses that a precise and transparent audit report can decrease the expectation gap and increase stakeholders’ trust (Gold et al., 2012). KAM disclosures include firm-specific information about an audit of financial statement (Bedard et al., 2016; Gimbar et al., 2016). They portray an individual picture of the main critical accounting topics or items in a company (Veite, 2018). According to stakeholder agency theory, KAM disclosures contribute to lowering information asymmetry and conflicts of interest between management and stakeholders and decreasing the expectation gap (Fuller, 2015). Stakeholder agency theory assumes heterogeneous interests between stakeholders and expects homogeneous interests within a stakeholder group. Furthermore, it accepts the rational behavior of the principal(s) and the agent(s), and the risk-neutrality of the agents. As we will discuss in the next chapter, archival research is the dominant research method used to analyze the macro-economic impacts of KAM disclosure on stakeholders’ reactions (e.g. Almulla & Bradbury, 2018).

In contrast to stakeholder agency theory, KAM disclosures can lead to adverse or no stakeholder reactions, in line with behavioral agency theory (Wiseman & Gomez-Mejia, 1998; Pepper & Gore, 2015). Behavioral agents are characterized by temporal discounting, preferences related to uncertainty, fairness expectations and loss aversion (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). Accepting behavioral aspects allows the principal(s) to have different levels of risk aversion and thus allows heterogeneity within a stakeholder group. Risk- averse principals are likely to evaluate KAM disclosures more negatively in comparison with other stakeholders (Veite, 2018), because they may be concerned about the reported management discretions regarding these accounting topics or items (Sirois et al., 2018). Recognition of irrational behavior and heterogeneity within a stakeholder group is very useful in experimental research (e.g. Klueber et al., 2018). Analysis of micro-economic and individual personal factors (e.g. degree of sophistication of investors) can be easily conducted by experiments, which we will describe in the next section. Adopting a special part of behavior theory, some researchers consider moral licensing and motivated reasoning to be cognitive bias problems (Asbahr & Ruhnke, 2018; Ratzinger-Sakel & Theis, 2017). According to these approaches, auditors feel more morally licensed to accept material misstatements by the client after the introduction of KAM disclosure. Thus, KAM disclosure is not an accountability mechanism, but a tool or license for unconsciously justifying an auditor’s decision to waive an adjustment (Asbahr & Ruhnke, 2018). In summary, KAM disclosure may be linked with increased, decreased or no impact on accounting quality, audit quality and stakeholder reactions based on stakeholder agency and behavioral agency theory.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW OF EMPIRICAL RESEARCH ON KAM

2.1. Sample selection, research framework and methods

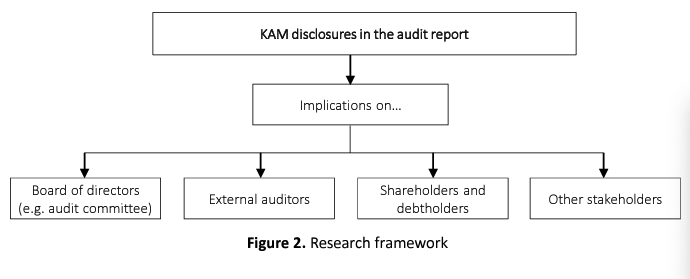

As the development of empirical KAM research is relatively new, there have been no explicit literature reviews to date. Bedard et al. (2016) conducted a literature review on US reform activities concerning auditor reporting (e.g. going concern opinions, audit partner signatures, CAM), and KAM disclosure is only one topic that is covered. Furthermore, Gimbar et al. (2016) presented the results of selected experimental studies concerning CAM’s influence on auditor litigation. Our structured literature review contributes to the present body of literature, because it focuses on KAM disclosures without any limitations regarding research methods or region, stresses the limitations of former studies and gives useful recommendations for research and practice. We rely on a stakeholder agency and behavioral agency framework and present the impact of KAM disclosure on (1) shareholders, (2) debtholders, (3) external auditors, (4) the board of directors, and (5) other stakeholders (see Figure 2).

To select our studies, we used several international databases (e.g. Web of Science, Google Scholar, Social Science Research Network (SSRN), EBSCO, ScienceDirect) and specific terms (e.g. “key audit matters”, “critical audit matters”) in combination with “audit reporting”, “audit quality”, or comparable terms. Restriction to a specific timeframe was not useful in light of the discipline’s newness. Some literature reviews on well-established research topics are limited to published or accepted journal articles to ensure appropriate quality and homogeneity of the included studies. However, for KAM, this strategy would lead to a rather low amount of studies. In line with the literature review conducted by Bedard et al. (2016), working papers and dissertations are included in our sample. Our structured analysis of research on KAM was conducted by considering all types of research methods, including experimental studies, archival studies and qualitative analyses (e.g. interviews, surveys, content analysis). Since KAM was recently regulated in many countries, the possibilities for archival research are still limited. Therefore, it is not surprising that research focuses on experimental studies (Kachelmeier et al., 2017). With one exception (Veite, 2018), only the consequences of KAM disclosures have been considered. Possible determinants of KAM or country-specific effects have not been analyzed. We only include English working papers, dissertations or journal articles in view of the international reach. KAM, CAM, RMM and JOA are included in our sample. If there are any significant differences with regard to the extended auditor reporting variables, we will emphasize them. Otherwise, in order to increase readability of our literature review, we only use the term KAM.

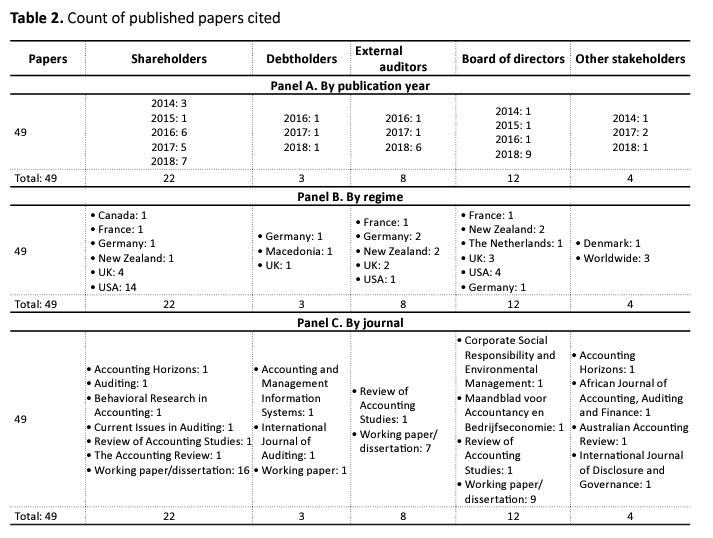

Table 2 provides an overview of the number of included contributions per stakeholder and their year of publication, the regions examined and the journals in which the contributions were published or the working papers. All studies were published or prepared within the last years (2014-2018), with a clear increase in the number of studies published in 2018. Most empirical research on KAM focuses on investors’ reactions in a US-American setting and adopt an experimental design. In addition, most research was published as working paper. In view of the latest regulation initiatives regarding KAM and the long review duration in top international journals, this is not surprising. We also identify more research activity in 2018 concerning the implications of KAM on the board of directors (e.g. management reporting, audit committee) and external auditors. Accounting and auditing journals are the primary publication strategies.

2.2. Shareholders

2.2.1. Results

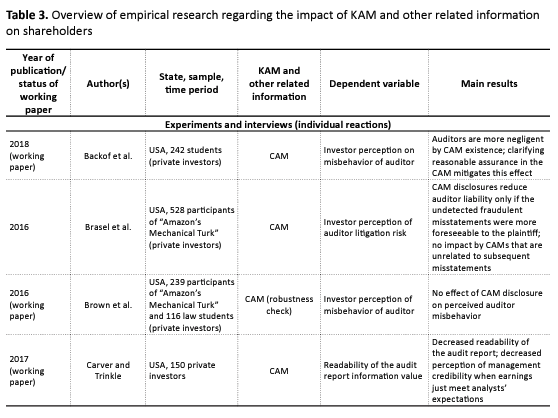

As a first research stream, eight US-American experiments analyze the impact of KAM disclosures on investors’ perceptions of auditor responsibility and litigation (Backof et al., 2018; Brasel et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2016; Doxey, 2014; Gimbar et al., 2016; Kachelmeier et al., 2017; Vinson et al., 2018; A. Wright & S. Wright, 2014; see Table 3). There is some evidence that KAM disclosures increase investors’ perception of auditors’ negligence (Backof et al., 2018; Vinson et al., 2018), responsibility (Kachelmeier et al., 2017), independence and credibility (Doxey, 2014) and liability (Gimbar et al., 2016). But KAM information can also decrease auditors’ responsibility in cases of a future bankruptcy (A. Wright & S. Wright, 2014). There are also insignificant results with regard to auditor litigation (Brasel et al., 2016) and misbehavior (Brown et al., 2016).

As a second research strength, seven experiments analyze the impact of KAM on value relevance and investor decisions (Christensen et al., 2014; Dennis et al., 2016; Kipp, 2017; Köhler et al., 2016; Pelzer, 2016; Rapley et al., 2018; Sirois et al., 2018) and six archival studies (Almulla & Bradbury, 2018; Bedard et al., 2018; Gutierrez et al., 2018; Lennox et al., 2017; Reid et al., 2015; Smith, 2017; see Table 3). The experimental studies indicate that specific KAM disclosure behavior can influence specific investors: a separate KAM paragraph in comparison to management’s footnotes (Christensen et al., 2014), a graphic illustration of KAMs (Dennis et al., 2016), detailed information about related audit procedures (Kipp, 2017), restrictions on professional investors (Köhler et al.,2016), on risk-seeking investors (Pelzer, 2016) and on one or two KAMs (Sirois et al., 2018). Rapley et al. (2018) found reduced investment intentions. The heterogeneity of investors’ preferences aligns with the behavioral agency framework.

In contrast to these results, the results of the archival studies are more heterogeneous. On the one hand, KAM is stated to be value relevant for investors (based on abnormal rents or trade volume; Almulla & Bradbury, 2018; Reid et al., 2015; Smith, 2017). On the other hand, some researchers found insignificant results (Bedard et al., 2018; Gutierrez et al., 2018; Lennox et al., 2017). Carver and Trinkle (2017), Smith (2017) also analyzed the impact of KAM on audit report readability and found mixed results (increased readability: Smith, 2017; decreased readability: Carver & Trinkle, 2017)

In sum, we argue that recent experimental and archival research on the influence of KAM disclosure on investors’ perceptions is rather heterogeneous. This result is in line with our stakeholder and behavioral agency framework. On the one hand, KAM disclosure may lead to an increased expectation gap, as risk-averse shareholders that perceive an increased audit risk may leave the company. They may blame external auditors for the increase in firm risks and don’t trust them with regard to irrational behavior. On the other hand, KAM disclosure can lead to a lower expectation gap as shareholders are better informed about the scope of external audits and, at minimum, risk-neutral or risk-seeking shareholders honor information transparency with capital engagement.

2.2.2. Limitations and research recommendations

Empirical research on behavioral auditing can be still classified as a niche (Simnett & Trotman, 2018), but experimental research on KAM disclosure has been well established recently. The international dominance of archival studies on empirical audit research with other topics is not useful for studying KAM disclosures. Our theoretical framework indicates that the individual characteristics of investors are very important for explaining the impact of KAM disclosures on value relevance. The assumption of a risk-neutral homogeneous shareholder group in line with classical agency theory is not realistic and thus has to be questioned. Thus, research that combines experimental and archival research design is necessary. The dominance of the US-American capital market in current research is problematic because of its lack of transferability to other regimes. KAM regulations have been implemented not only in the USA, but in many other countries. Other settings, such as the EU, should be included in future research. For experiments, reliance on students and “Amazon’s Mechanical Turk” participants is a very popular research strategy to measure private investors’ behavior. However, due to the limited validity of this research, future researchers should directly question different investors (Köhler et al., 2016; Pelzer, 2016). As the current research mainly concentrates on private investors, inclusion of more professional investors and explanation of the main differences between private and professional investors is necessary (Köhler et al., 2016). It is important to note that a variety of К AM-related accounting topics have been examined in experimental settings (e.g. goodwill impairment), which lowers the comparability of the results. Countryspecific effects of the equity market and socio-economic environment (e.g. shareholder rights, legal enforcement) should be included in future cross-country archival studies.

Furthermore, we encourage researchers to conduct interviews and surveys with investors or perform case studies with investors in a specific company to gain more insight into investment decisions after KAM disclosure. Linguistic analyses of KAM disclosure are most useful to analyze decision usefulness for investors. As many researchers criticize the limited transparency and readability of audit reports published in recent years (Carver & Trinkle, 2017), more research on KAM readability and external auditors’ tone management is needed.

2.3. Debtholders

2.3.1. Results

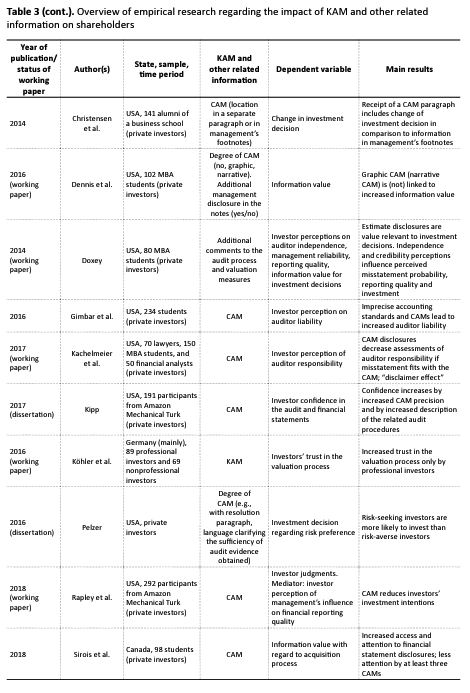

In contrast to shareholders, we identify only three studies on debtholders (Boolaky & Quick, 2016; Porump et al., 2018; Trpeska et al., 2017), which have mixed results (see Table 4). While Trpeska et al. (2017) confirmed the informational value of KAM disclosure with an online survey of corporate loan officers, Boolaky and Quick (2016) did not find that bank directors’ perceptions change as a result of KAM disclosures. Additionally, based on an archival study, Porump et al. (2018) found that an increased amount of RMM is connected with less favorable loan contracting terms.

2.3.2. Limitations and research recommendations

Recent empirical KAM research on debtholders reactions is not valid and of low quantity unlike research on investors. As debtholders are key corporate stakeholders, especially in small and medium-sized entities, we encourage researchers to include this stakeholder group in future designs. Interestingly, no experimental research has been conducted so far. This research gap should be decreased in light of the heterogeneous preferences of debtholders and their unclear reaction to KAM disclosures. In line with the behavior of shareholders, individual risk preferences may lead to increased or decreased loan contracting conditions for a company. It is most useful to analyze the link between KAM disclosure and debtholders’ reactions using archival data. In line with our recommendations regarding investors’ reactions, future research should conduct cross-country studies on the impact of KAM disclosure on debtholders’ reactions.

2.4. External auditors

2.4.1. Results

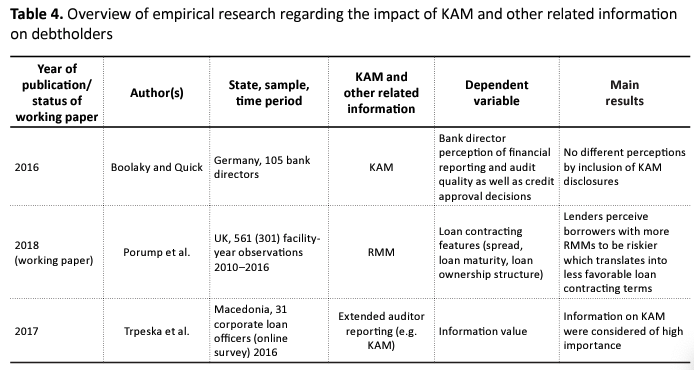

We identify three experiments (Asbahr & Ruhnke, 2018; Pelzer, 2016; Ratzinger-Sakel & Theis, 2017) and five archival studies (Almulla & Bradbury, 2018; Bedard et al., 2018; Gutierrez et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Reid et al., 2018) that examine the impact of KAM disclosure on external auditors’ behavior (see Table 5). In most cases, KAM disclosure did not change auditors’ behavior concerning their professional judgment of the reasonableness of a biased accounting estimate (Asbahr & Ruhnke, 2018), the value of information (Pelzer, 2016), audit fees (Bedard et al., 2018; Gutierrez et al., 2018; Reid et al.,) and audit report lag (Bedard et al., 2018). Only Ratzinger-Sakel and Theis (2017), Almulla and Bradbury (2018) and Li et al. (2018) found significant auditor reactions to KAM disclosure as audit fees increase (Almulla & Bradbury, 2018; Li et al., 2018) and auditors exhibit less skeptical judgment (Ratzinger-Sakel & Theis, 2017). In contrast to other stakeholders, a variety of different regimes (Germany, the USA, New Zealand, France, the UK) were included in this stream of research.

2.4.2. Limitations and research recommendations

Interestingly, the surveys and experiments directly address external auditors. However, with the exception of Asbahr and Ruhnke’s (2018) study, the number of participants in these studies is rather low. Therefore, the validity of the studies is limited. Pelzer (2016) mentioned the risks of misinterpretation and use of boilerplate information when discussing KAM. Thus, we encourage future researchers to survey external auditors to determine how they actively contribute to better transparency and readability of KAM disclosures, as regulators have criticized the lack of transparency of audit reports. As accounting topics, which lead to KAM disclosures, are often very complex for external stakeholders, the tone of explanations in the audit report may have a major impact on the expectation gap. Future archival research should analyze audit-related determinants (e.g. Big Four audits, industry specialists, (non) audit fees, audit report lag) on KAM readability. Most recent archival studies used audit fees as a proxy for audit quality (Almulla & Bradbury, 2018; Bedard et al., 2018; Gutierrez et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Reid et al., 2018). We are aware that the audit fee proxy has limited validity, because it can reflect both audit independence and audit efficiency. Non audit fees, auditor tenure and audit partner signature can be more useful for analyzing auditor independence. As many countries have recently implemented KAM disclosure rules, learning effects of external auditors will have a major impact on auditor reporting. To do so, time series analyses are recommended. As we will describe in the next section, cooperation between audit committees and external auditors should be included in future research. Also, research should analyze whether the audit committee has a complementary or substitutional relationship with the external auditor, which may lead to increased or decreased audit fees.

2.5. Board of directors

2.5.1. Results

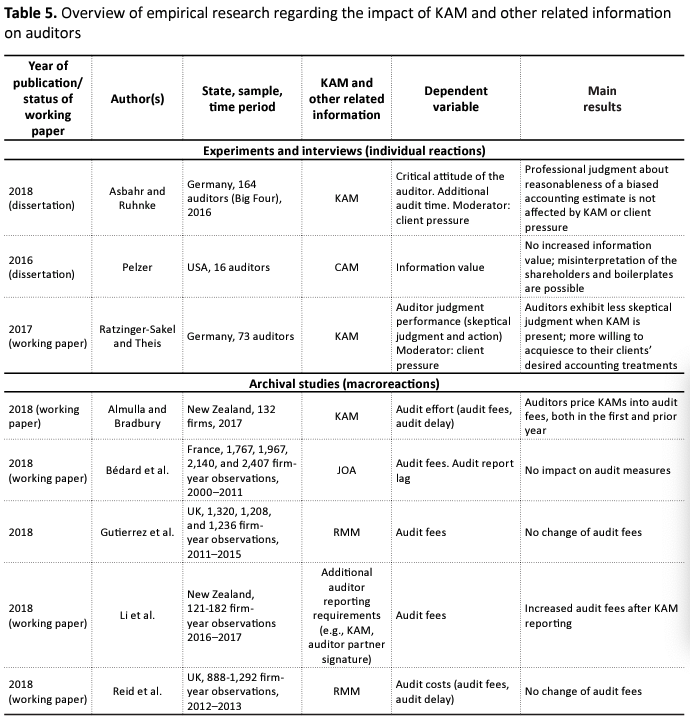

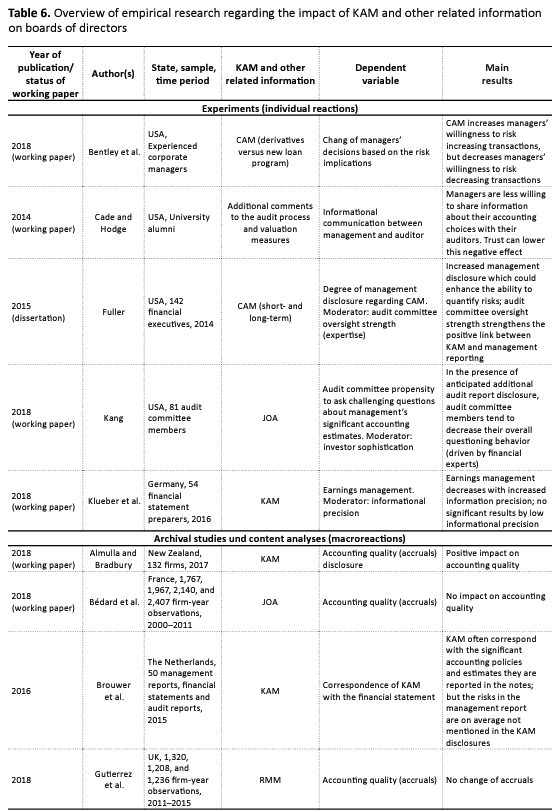

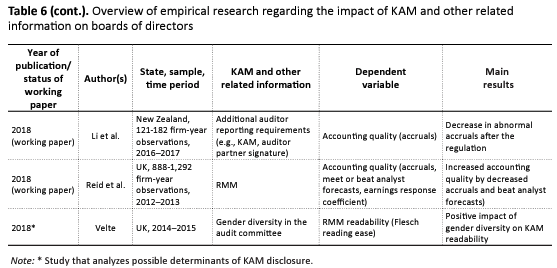

Not only share- and debtholders and external auditors, but also a major impact of KAM disclosure on board of directors is expected in empirical research. Thus, KAM disclosure are linked with management decisions, e.g. earnings management or management reporting. According to our stakeholder agency-theoretical framework, extended auditor reporting should lead to decreased information asymmetries and conflicts of interests between management, external auditor and capital market. We identify five experiments (Bentley et al., 2018; Cade & Hodge, 2014; Fuller, 2015; Kang, 2018; Klueber et al., 2018) and six archival studies (Almulla & Bradbury, 2018; Bedard et al., 2018; Brouwer et al., 2016; Gutierrez et al., 2018, Li et al., 2018; Reid et al., 2018) that examine the impact of KAM on the board of directors (see Table 6).

Most studies explore the impact of KAM disclosure on earnings management (Klueber et al., 2018; Almulla & Bradbury, 2018; Bedard et al., 2018; Gutierrez et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Reid et al., 2018). While there is evidence of a positive link between KAM and accounting quality (Klueber et al., 2018; Almulla & Bradbury, 2018; Li et al., 2018; Reid et al., 2018), some insignificant results were also found (Bedard et al., 2018; Gutierrrez et al., 2018).

KAM disclosure may influence not only earnings management, but also management reporting and management decisions (Bentley et al., 2018; Cade & Hodge, 2014; Brouwer et al., 2016). Based on a content analysis, Brouwer et al. (2016) stated that KAM often corresponds with accounting policies and estimates in the notes. However, risks related to the management reports are not mentioned in KAM disclosures. Mixed results are also found by Bentley et al. (2018): managers are willing to increase (decrease) risk increasing (decreasing) transactions. According to Cade and Hodge (2014), managers share less information with their auditor about their accounting choices after the KAM regulations.

Three studies examined the role of the audit committee as a monitoring institution (Fuller, 2015; Kang, 2018; Veite, 2018). While Kang (2018) stated that the audit committee decreases their overall questioning behavior regarding management when KAM is disclosed, Fuller (2015) found that the strength of the audit committee’s oversight moderates the positive association between KAM disclosure and management reporting. Veite (2018) is the only author in our sample that analyzed the impact of audit committee composition (gender diversity) on RMM readability and stated a positive link.

2.5.2. Limitations and research recommendations

With one exception (Klueber et al., 2018), the experiments were performed only in a US-American setting. We already stated that the empirical results are not transferable to other regimes. From an international perspective, one- and two-tier systems of corporate governance are very different in terms of composition and to KAM disclosure. In addition, the US-American one-tier system (e.g. by Bentley et al., 2018) is not comparable to the German two-tier system (Klueber et al., 2018). This is mainly important in relation to the role of audit committees in one-tier and two-tier systems. Audit committees in one-tier systems tend to have increased information access, but can have decreased independence in comparison to committees in two-tier systems. For this reason, research on two-tier systems is recommended.

Few earnings management studies based on experiments have been conducted to date (Klueber et al., 2018). We identify a research gap with regard to empirical qualitative research (surveys, interviews, case studies) on the impact of KAM disclosure on the reactions of boards of directors. Both management and audit committees should be addressed in future research to gain more information about the cooperation process between the audit committee and external auditor and the correspondence between management reporting (e.g. in the notes or management report) and the KAM disclosure of the external auditor. It is also relevant to analyze the impact of audit committee composition (e.g. members with financial expertise or industry expertise) on KAM disclosure, as the audit committee and external auditor must discuss the audit focal points, which can be relevant for the external auditor’s choice of KAM to disclose in the audit report (Veite, 2018).

Most earnings management studies, based on archival data, use accruals measures. In line with many critics of such measures in former literature (Gaynor et al., 2016), we stress the limited validity of accruals. To increase the sensitivity of archival research, future researchers should include other accounting quality variables, such as restatements, meeting or beating analysts’ earnings forecasts and accounting conservatism. Accruals measures only pertain to book-related accounting policies. During recent years, archival research on other accounting, auditing or corporate governance issues has integrated real earnings management (Gaynor et al., 2016). This kind of extension can be very useful in empirical KAM research, too. As earnings management is dependent on country effects (e.g. code versus case law, the strength of legal enforcement), we encourage researchers to conduct cross-country studies in the future.

2.6. Other stakeholders

2.6.1. Results

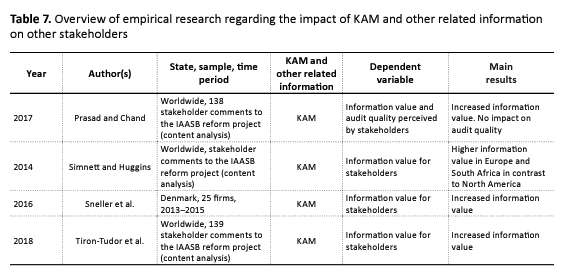

Similar to the results of debtholders, we know very little about the impact of KAM disclosure on other stakeholders (e.g. customers, suppliers, employees, the state). In our sample, four studies address a broad range of stakeholders (Prasad & Chand, 2017; Simnett & Huggins, 2014; Sneller et al., 2017; Tiron-Tudor et al., 2018) without any explicit theoretical framework (see Table 7). Prasad and Chand (2017), Simnett and Huggins (2014) and Tiron- Tudor et al. (2018) used stakeholders’ comments on the IAASB reform project in content analyses and found an increased informational value for stakeholders. A content analysis of annual and audit reports performed by Sneller et al. (2017) also had the same results. Additionally, no impact on audit quality was found by Prasad and Chand (2017).

2.6.2. Limitations and research recommendations

Not only the amount of studies on the impact of KAM disclosures on other stakeholders, but also the focus on qualitative research (content analyses) lowers their relevance. Future researchers should conduct interviews, surveys and case studies on other stakeholders’ perceptions of KAM (e.g. customers’ awareness, suppliers’ attraction, employee relationships). Furthermore, empirical quantitative research on other stakeholders should be both experimental and archival nature. The variety of regulations on KAM disclosure implemented in recent years are not limited to share- and debtholders, external auditors, and boards of directors. Thus, increasing trust of other stakeholders is an important goal for future research. PIEs are confronted with increased regulations concerning not only financial accounting, auditing and corporate governance, but also non-financial reporting (e.g. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reporting or integrated reporting). As non-financial reporting and CSR assurance can be classified as key topics in research, regulation and practice, the interdependencies between KAM disclosure, integrated reporting and non-financial issues should be addressed from a broader stakeholder perspective in future research.

SUMMARY

Capital market trust in financial reporting and external audit quality has decreased after the financial crisis of 2008-2009. Information overload in annual reports and audit reports is linked with decreased decision usefulness for shareholders and other stakeholders. As a result, auditor reporting (e.g. KAM disclosures) have been extended by various institutions (e.g. FRC, 2013; IAASB, 2015; PCAOB, 2017). Regulators assume KAM disclosures are linked with lower information asymmetry and expectation gap and thus increase financial reporting and audit quality.

In contrast to former literature reviews on extended auditor reporting (Gimbar et al., 2016; Bedard et al., 2016), we rely on 49 empirical studies on KAM disclosure and conduct a stakeholder-oriented structured literature review. We identified five major streams of empirical research that analyze the impact of KAM disclosure on stakeholders’ reactions: those focusing on (1) shareholders (e.g. investors’ perceptions of auditors’ responsibility and litigation, value relevance and investors’ decisions); (2) debtholders (e.g. loan contracting terms); (3) external auditors (e.g. audit processes and audit fees); (4) boards of directors (e.g. earnings management); and (5) other stakeholders (e.g. informational value for suppliers and customers). Most of the included studies use experimental or archival data and analyze the impact of KAM disclosure on investor reactions in a US-American setting. However, the intended goal of KAM regulations is still controversial, as evidenced by the mixed empirical results. Although there are some indications of decreased earnings management behavior, most studies find no significant changes in auditor behavior. Furthermore, there are many insignificant results with regard to shareholders’ reaction in line with our stakeholder and behavioral agency framework. In order to increase the validity of empirical KAM research, we recommend a variety of research topics for the five streams of research. In particular, cross-country studies are needed due to the international regulation of KAM during recent years. Interestingly, behavioral research on auditing has been established within the field of empirical KAM research, but not related to other audit topics. We see a major need to include a mixture of research methods to explain the impact of KAM disclosure on stakeholders’ reactions. As stakeholders’ preferences are heterogeneous and many stakeholder groups have limited knowledge and experience with KAM disclosure, external auditors should provide a transparent and readable audit report without any boilerplate information. Otherwise, KAM regulations result in opposite stakeholder reactions (e.g. increased expectation gap and decreased stakeholder trust in financial accounting and external audits). Thus, our results are not only relevant for future research but also for regulators and practice. Future developments in KAM regulation (e.g. increased precision of audit reporting standards, possible extension of companies) have to be critically discussed in light of the limited evidence regarding increased accounting and audit quality. The results of our literature review are especially relevant for the board of directors and top management decisions. Recent empirical research on KAM disclosure indicates that KAM disclosure may have an impact on earnings management and management reporting behavior (e.g. risk reporting). Furthermore, the audit committee as a monitoring institution of the board of directors is linked to auditor cooperation and KAM disclosure. KAM disclosure and external audit in total should be classified as a major challenge to increase stakeholder trust after the financial crisis. Thus, management should be aware of the price competition and supplier concentration on the audit market. Perceived audit quality may be low if the audit committee does not grant enough resources and fees for the external auditors.

REFERENCES

- Almulla, M., & Bradbury, M. E. (2018). Auditor, Client, and Investor Consequences of the Enhanced Auditor’s Report (Working Paper).

- Antle, R. (1982). The Auditor as an Economic Agent. Journal of Accounting Research, 20(2), 503-527.

- Asbahr, K., & Ruhnke, K. (2018). Real Effects of Reporting Key Audit Matters on Auditors‘ Judgment of Accounting Estimates (Working Paper).

- Backof, A. G., Bowlin, K., & Goodson, B. M. (2018). The Importance of Clarification of Auditors’ Responsibilities Under the New Audit Reporting Standards (Working Paper).

- Bédard, J., Coram, P., Esphahbodi, R., & Mock, T. J. (2016). Does Recent Academic Research Support Changes to Audit Reporting Standards? Accounting Horizons, 30, 255-275.

- Bédard, J., Gonthier-Besacier, N., & Schatt, A. (2014). Costs and Benefits of Reporting Key Audit Matters in the Audit Report: The French Experience (Working Paper).

- Bédard, J., Gonthier-Besacier, N., & Schatt, A. (2018). Consequences of Expanded Audit Reports: Evidence from the Justifications of Assessments in France (Working Paper).

- Bentley, J. W., Lambert, T. A., & Wang, E. Y. (2018). The Effect of Increased Audit Disclosure on Managerial Decision Making: Evidence from Disclosing Critical Audit Matters (Working Paper).

- Boolaky, P. K., & Quick, R. (2016). Bank Directors’ Perceptions of Expanded Auditor’s Reports. International Journal of Auditing, 20(2), 158-174.

- Brasel, K., Doxey, M., Grenier, J., & Reffett, A. (2016). Risk Disclosure Preceding Negative Outcomes. The Accounting Review, 91(5), 1345-1362.

- Brouwer, A., Eimers, P., & Langendijk, H. (2016). The relationship between key audit matters in the new auditor’s report and the risks reported in the management report and the estimates and judgments in the notes to the financial statements. Maandblad voor Accountancy en Bedrijfseconomie (MAB), 90, 580-613.

- Brown, T., Majors, T., & Peecher, M. (2016). The Impact of a Higher Intent Standard on Auditors’ Legal Exposure and the Moderating Role of Jurors’ Legal Knowledge (Working Paper).

- Cade, N., & Hodge, F. (2014). The effect of expanding the audit report on managers’ communication openness (Working Paper).

- Carver, B. T., & Trinkle, B. S. (2017). Nonprofessional Investors’ Reactions to the PCAOB’s Proposed Changes in the Standard Audit Report (Working Paper).

- Chow, C. (1982). The demand for external auditing. The Accounting Review, 57(2), 272-291.

- Christensen, B., Glover, S., Steven, M., & Wolfe, C. (2014). Do critical audit matter paragraphs in the audit report change nonprofessional investors’ decision to invest? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 33(4), 71-93.

- Church, B. K., Davis, S. M., & McCracken, S. A. (2008). The Auditor’s Reporting Model: A Literature Overview and Research Synthesis. Accounting Horizons, 22(1), 69-90.

- DeAngelo, L. (1981). Size and Audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183-199.

- Dechow, P. M., Ge, W. & Schrand, C. (2010). Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxoxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2-3), 344-401.

- DeFond, M., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2-3), 275-326.

- Dennis, S. A., Griffin, J. B., & Johnstone, K. M. (2016). The Value Relevance of Managers’ and Auditors’ Disclosures about Material Measurement Uncertainty (Working Paper).

- Doxey, M. M. (2014). The Effects of Auditor Disclosures Regarding Management Estimates on Financial Statement Users’ Perceptions and Investments (Working Paper).

- Eilifsen, A., Knechel, W., & Wallage, P. (2001). Application of the Business Risk Audit Model. A Field Study. Accounting Horizons, 15(3), 193-207.

- Elliott, W. B., Fanning, K., & Peecher, M. E. (2016). Do Investors Value Financial Reporting Quality Beyond Estimated Fundamental Value? And, Can Better Audit Reports Unlock This Value? (Working Paper).

- Ferguson, A. (2005). A Review of Australian Audit Pricing Literature. Accounting Research Journal, 18(2), 54-62.

- FRC (2013). Consultation Paper: Revision to ISA (UK and Ireland) 700. Requiring the auditor’s report to address risks of material misstatement, materiality, and a summary of the audit scope.

- Fuller, S. (2015). The Effect of Auditor Reporting Choice and Audit Committee Oversight Strength on Management Financial Disclosure Decisions (Dissertation). Georgia State University.

- Gaynor, L. M., Kelton, A. S., Mercer, M., & Yohn, T. L. (2016). Understanding the Relation between Financial Reporting Quality and Audit Quality. Auditing, 35(4), 1-22.

- Gimbar, C., Hansen, B., & Ozlanski, M. (2016). Early Evidence on the Effects of Critical Audit Matter on Auditor Liability. Current Issues in Auditing, 10(1), A24-A33.

- Gold, A., Gronewold, U., & Pott, C. (2012). The ISA 700 Auditor’s Report and the Audit Expectation Gap. Do Explanations Matter? International Journal of Auditing, 16(3), 286-307.

- Gros, M., & Worret, D. (2014). The challenge of measuring audit quality: some evidence. International Journal of Critical Accounting, 6(4), 345-374.

- Gutierrez, E., Minutti-Meza, M., Tatum, K. W., & Vulcheva, M. (2018). Consequences of adopting an expanded auditor’s report in the United Kingdom. Review of Accounting Studies, 23(4), 1543-1587.

- Haut Conseil des Commissaires aux Comptes (2006). NEP-705 Justification des appréciations. Normes d’Exercice professionnel des Commissaires aux Comptes.

- IAASB (2015). The new auditor’s report: Greater transparency into the financial statement audit. New York.

- Ittonen, K. (2012). Market reactions to qualified audit reports: Research approaches. Accounting Research Journal, 25(1), 8-24.

- Jensen, M., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm. Managerial Behaviour, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360.

- Kachelmeier, S., Schmidt, J., & Valentine, K. (2017). The Disclaimer Effect of Disclosing Critical Audit Matters in the Auditor’s Report (Working Paper).

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-292.

- Kang, Y. J. (2018). Are Audit Committees More Challenging Given a Sophisticated Investor Base? Does the Answer Change Given Anticipation of Additional Mandatory Audit Report Disclosure (Working Paper).

- Kipp, P. (2017). The Effect of Expanded Audit Report Disclosures on Users’ Confidence in the Audit and the Financial Statements (Dissertation). University of South Florida.

- Klueber, J., Gold, A., & Pott, C. (2018). Do Key Audit Matters Impact Financial Reporting Behavior? (Working Paper).

- Koehler, A. G., Ratzinger-Sakel, N. V. S., & Theis, J. C. (2016). The Effects of Key Audit Matters on the Auditor’s Report’s Communicative Value (Working Paper).

- Koh, H. C., & Woo, E.-S. (1998). The expectation gap in auditing. Managerial Auditing Journal, 13(3), 147-154.

- Kraakman, R. (1986). Gatekeepers. The anatomy of a third-party enforcement strategy. Journal of Law, Economics and Organizations, 2(1), 53-104.

- Larcker, D. F., & Rusticus, T. O. (2010). On the use of instrumental variables in accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 49(3), 186-205.

- Lennox, C., Schmidt, J., & Thompson, A. (2017). Are the Expanded Model of Audit Reporting Informative to Investors? (Working Paper).

- Li, H. A., Hay, D., & Lau, D. (2018). Assessing the Impact of the New Auditor’s Report (Working Paper).

- Liggio, S. (1974). The Expectation Gap. The Accountant’s Legal Waterloo? Journal of Contemporary Business, 3, 27-44.

- Light, R., & Smith, P. (1971). Accumulating Evidence: Procedures for Resolving Contradictions among Different Research Studies. Harvard Educational Review, 41(4), 429-471.

- Mock, T. J., Bédard, J., Coram, P. J., Davis, S. M., Espahbodi, R., & Warne, R. C. (2013). The Audit Reporting Model: Current Research Synthesis and Implications. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 32(1), 323-351.

- PCAOB (2017). The auditor’s report on an audit of financial statements when the auditor expresses an unqualified opinion and related amendments to PCAOB standards (PCAOB release No. 2017-001). New York.

- Pelzer, J. R. E. (2016). Understanding Barriers to Critical Audit Matter Effectiveness: A Qualitative and Experimental Approach (Dissertation). Floria State University.

- Pepper, A., & Gore, J. (2015). Behavioral Agency Theory New Foundations for Theorizing About Executive Compensation. Journal of Management, 41(4), 1045-1068.

- Porter, B. (1993). An Empirical Study of the Audit Expectation-Performance Gap. Accounting and Business Research, 24, 49-68.

- Porump, V.-A., Karaibrahimoglu, Y. Z., Lobo, G. J., Hooghiemstra, R., & de Waard, D. (2018). Is More Always Better? Disclosures in the Expanded Audit Report and Their Impact on Loan Contracting (Working Paper).

- Prasad, P., & Chand, P. (2017). The Changing Face of the Auditor’s Report: Implications for Suppliers and Users of Financial Statements. Australian Accounting Review, 27, 348-367.

- Rapley, E. T., Robertson, J. C., & Smith, J. L. (2018). The Effects of Disclosing Critical Audit Matters and Auditor Tenure on Investors’ Judgments (Working Paper).

- Ratzinger-Sakel, N. V. S., & Theis, J. (2017). Does considering key audit matters affect auditor judgment performance? (Working Paper).

- Reid, L. C., Carcello, J. V., Li, C., & Neal, T. L. (2015). Are Auditor and Audit Committee Report Changes Useful to Investors? Evidence from the United Kingdom (Working Paper).

- Reid, L. C., Carcello, J. V., Li, C., & Neal, T. L. (2018). Impact of Auditor Report Changes on Financial Reporting Quality and Audit Costs: Evidence from the United Kingdom (Working Paper).

- Ross, S. (1973). The Economic Theory of Agency: The Principal’s Problem. American Economic Review, 63, 134-139.

- Simnett, R., & Huggins, A. (2014). Enhancing the Auditor’s Report: To What Extent is There Support for the IAASB’s Proposed Changes? Accounting Horizons, 28(4), 719-747.

- Simnett, R., & Trotman, K. T. (2018). Twenty-five Year Overview of Experimental Auditing Research: Trends and Links to Audit Quality. Behavioral Research in Accounting (online first).

- Sirois, L., Bédard, J., & Bera, P. (2018). The Informational Value of Key Audit Matters in the Auditor’s Report: Evidence from an Eye-tracking Study. Accounting Horizons, 32(2), 141-162.

- Smith, K. W. (2017). Tell Me More: A Content Analysis of Expanded Auditor Reporting in the United Kingdom (Working Paper).

- Sneller, L., Bode, R., & Klerx, A. (2017). Do IT matters matter? IT-related key audit matters in Dutch annual reports. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 14(2), 139-151.

- Tiron-Tudor, A., Cordos, G. S., & Fulöp, M. T. (2018). Stakeholders’ perception about strengthening the audit report. African Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 6(1), 43-69.

- Trpeska, M., Atanasovski, A., & Bozinovska, Z. (2017). The relevance of financial information and contents of the new audit report for lending decisions of commercial banks. Accounting and Management Information Systems, 16(4), 455-471.

- Velte, P. (2018). Does gender diversity in the audit committee influence key audit matters’ readability in the audit report? UK evidence. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(5), 748-755.

- Vinson, J. M., Robertson, J. C., & Cockrell, R. C. (2018). The Effects of Critical Audit Matter Removal and Duration on Jurors’s Assessment of Auditor Negligence (Working Paper).

- Watts, R., & Zimmerman, J. (1983). Agency Problems, Auditing, and the Theory of the Firm: Some Evidence. Journal of Law & Economics, 26, 613-633.

- Wiseman, R. M., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (1998). A Behavioral Agency Model of Managerial Risk Taking. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 133-153.

- Wright, A. M., & Wright, S. (2014). Modification of the Audit Report: Mitigating Investor Attribution by Disclosing the Auditor’s Judgment Process. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 26, 35-50.