Perceived benefits of balanced scorecard implementation: some preliminary evidence

Published: Sept. 18, 2014

Latest article update: Dec. 8, 2022

Abstract

Since its introduction more than 20 years ago the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) has garnered the interest of both academics and practitioners. In the ‘official’ practitioner-oriented literature the BSC’s main proponents Kaplan and Norton have touted the concept’s potential performance enhancing effects. Academics have been more skeptical, and have not found a clear-cut relationship between the use of the BSC and organizational performance. It appears that some uses of the BSC may increase performance, while other types of BSC use might decrease it. Still, research has shown that the concept is widely used in practice, more than 20 years after its introduction. The longevity of the BSC indicates that organizations are satisfied with the concept and find at least aspects of it useful and beneficial. The extant literature, however, gives limited insight into the aspects of the BSC that managers appreciate. This leads to the following research question: What aspects of the BSC are perceived as beneficial by consultants and managers? Using data from qualitative interviews with BSC consultants and users, this paper explores the perceived benefits associated with the implementation of the BSC. The data show the perceived benefits are related to the concept’s fit with the local institutional context in Scandinavia, e.g. in terms of balancing shareholder and stakeholder demands. In addition, consultants and managers highlight social and behavioral changes as a result of BSC implementation

Keywords

Benefits, balanced scorecard, implementation, management concepts

Introduction

The balanced scorecard. The Balanced Scorecard (BSC) has since its introduction more than 20 years ago as a multi-dimensional performance measurement system (Kaplan & Norton, 1992) garnered much interest not only in academic circles (Banchieri, Planas, & Rebull, 2011; Hoque, 2014; Lueg & e Silva, 2013; Perkins, Grey & Remmers, 2014) but also in practice as a management tool (Rigby & Bilodeau, 2009, 2011, 2013). In the ‘official’ practitioner-oriented BSC literature the concept’s main proponents Kaplan and Norton have touted the concept’s performance enhancing potential (e.g. Kaplan & Norton, 2004, 2006; Kaplan & Norton, 2008). In contrast, academics have been more skeptical of the concept’s merits, and have pointed out that the concept can have dysfunctional effects and in some instances may hinder innovation and learning (e.g. Antonsen, 2014; Norreklit, 2003; Norreklit, Norreklit, Mitchell & Bjomenak, 2012; Voelpel, Leibold & Eckhoff, 2006). Researchers have also not found a clear-cut relationship between the use of the BSC and organizational performance. Instead, it appears that effects of the BSC depend to a large part on how the concept is interpreted and used. BSC use which complements the organization’s strategy may increase organizational performance, while other types of BSC use may decrease the organization’s performance (e.g. Braam & Nijssen, 2004; Davis & Albright, 2004; De Geuser, Mooraj, & Oyon, 2009).

Motivation. The aim of this paper is to investigate the perceived benefits of BSC implementation and usage. There have been numerous debates on the usefulness of the BSC, and some academics have been skeptical of the concept’s merits. However, the fact that the BSC is widely adopted, implemented and used in practice (e.g. Al Sawalqa, Holloway & Alam, 2011; Maisel, 2001; Nielsen & Sorensen, 2004; Rigby & Bilodeau, 2013; Silk, 1998; Speckbacher, Bischof & Pfeiffer, 2003; Stemsrudhagen, 2004) is an indication that the concept is useful and may have potential benefits. The extant literature, however, gives limited insight into the aspects of the BSC that managers appreciate. This leads to the following research question: What aspects of the BSC are perceived as beneficial by consultants and managers? Following suggestions by Al Sawalqa et al. (2011, p. 206) the above research question is addressed by drawing on data from a qualitative study in which 61 BSC consultants and users were interviewed.

Contribution. The paper adds to the BSC literature by providing some insight into the perceived benefits associated with implementation of the BSC. To some extent BSC researchers have a tendency to focus on negative stories and failures (Hoque, 2014). Hoque (2014, p. 49) points out that ‘‘there is a dearth of positive stories in the research literature about the application of the balanced scorecard in organizations ”. Hence, this paper can provide some preliminary insights into what organizations find beneficial about the BSC. In this regard, it should be pointed out that we discuss the perceived problems associated with BSC implementation in a related paper (Madsen & Stenheim, 2014). Our two papers should be read in connection with each other as the implementation of the BSC may have both positive and negative consequences. In addition, we believe this paper also has practical implications for managers in organizations that are currently working with or considering adopting and implementing the BSC. Knowing more about potential benefits (and problems) could assist managers in making informed decisions about whether or not to adopt and implement the BSC.

Structure. The paper proceeds in the following way. Section 1 briefly reviews the literature which deals with benefits and problems related to the BSC. Section 2 outlines the research methodology. Then sections 3 and 4 report on the interviews with consultants and users of the BSC, respectively. The final part of the paper summarizes the main findings and contributions, discusses limitations and directions for future work in the area.

1. Benefits and problems associated with the implementation of the BSC

1.1. Extant research on BSC implementation. Several recent literature reviews have shown that the academic literature about the BSC has grown considerably over the last 10 to 15 years, and has branched out in different directions (Banchieri et al., 2011; Hoque, 2014; Lueg & e Silva, 2013; Perkins et al., 2014). Although some studies have looked at the implementation, design and use of the BSC (e.g. Brudan, 2005; Lawrie & Cobbold, 2004; Speck-bacher et al., 2003), there is little systematic research that has looked specifically on the benefits of BSC implementation. Instead, much of the academic research has been critical of the BSC and has mostly focused on negative stories and failures (Hoque, 2014).

Survey research such as Bain & Company’s longitudinal survey of management tools (Rigby & Bilodeau, 2009, 2011, 2013) has shown that the concept is widely used in practice and that managers are generally satisfied with their use of the BSC. Since the concept has been around for more than two decades, this is in many ways a testament to its durability (cf. Hoque, 2014). It is also an indication that users perceive the concept as useful and that for most organizations the benefits outweigh the costs (e.g. in terms of time and resources). However, we know little about what aspects of the BSC that organizations appreciate and find useful.

1.2. The interpretive space of the BSC. When discussing the benefits and problems associated with the implementation of the BSC, it is important to keep in mind that the BSC is not a ‘stable entity’ which means the same thing to different actors operating in different organizations or contexts (Braam, 2012; Braam, Benders & Heusinkveld, 2007; Braam, Heusinkveld, Benders & Aubel, 2002; Braam & Nijssen, 2004; Dechow, 2012; Norreklit, 2003; Soderberg, Kalagnanam, Sheehan & Vaidya- nathan, 2011). The BSC exists in many forms and versions in different books and articles. This is also the case when it is implemented as a practice in different organizations. Why is this so? Many researchers have pointed out that the BSC possesses ‘interpretive space’ and is to a large extent theoretical and abstract (Aidemark, 2001; Ax & Bjomenak, 2005; Braam, 2012; Braam et al., 2007; Braam & Nijssen, 2004; Hansen & Mouritsen, 2005; Madsen, 2012; Modell, 2009). This means that the concept can be interpreted and understood in different ways. As a result, the BSC can, for instance, be implemented as a ‘performance measurement system’ or as a ‘strategic management system’ (Brudan, 2005; Lawrie & Cobbold, 2004; Perkins et al., 2014; Speckbacher et al., 2003).

1.3. Problems associated with BSC implement- tation. Many studies have shown that organizations may run into different types of problems in the BSC implementation process (Antonsen, 2014; Kasurinen, 2002; Madsen & Stenheim, 2014; Modell, 2012; Norreklit, Jacobsen & Mitchell, 2008; Wickrama- singhe, Gooneratne & Jayakody, 2007). The problems that organizations face range from conceptual and technical issues to social and political issues (Madsen & Stenheim, 2014). Conceptual issues are related to understanding and interpreting the concept, while technical issues may arise when developing a technical infrastructure to support the BSC. Social and political issues are also common, as the implementation of the BSC may trigger many types of behavioral responses from individuals and groups in the organization, e.g. resistance and a lack of participation (Madsen & Stenheim, 2014).

1.4. Benefits associated with BSC implementation. As noted in the introduction, the jury is still out on whether the BSC increases organizational performance. Researchers have not found a clear-cut relationship between the use of the BSC and organizational performance (Braam & Nijssen, 2004; Davis & Albright, 2004; De Geuser et al., 2009). An important finding from these studies is that certain uses of the BSC can increase organizational performance since they complement and assist in the implementation of an organization’s strategy (Braam & Nijssen, 2004; De Geuser et al., 2009). Other forms of BSC usage, such as use as a performance measurement system completely decoupled from the organization’s strategy, might decrease performance (Braam & Nijssen, 2004).

In another study, Lucianetti (2010) found that the main benefit of the BSC lies in the use of strategy maps, which are central components of Kaplan and Norton’s more recent books about the BSC. A possible explanation for why strategy maps have a performance enhancing effect could be that organizations that go through the process of developing strategy maps obtain insights into their business operations and how they create value, something that organizations which use the BSC predominantly as a ‘measurement system’ may not. This suggests that the BSC may deliver the most beneficial effects when it is used for ‘strategizing’, e.g. discussing and developing strategies in praxis (cf. Jarzabkowski, Balogun & Seidl, 2007; Whittington, 2003).

2. Methods and data

2.1. Research approach. Our research was conducted using a largely qualitative and interpretive approach. This type of research approach was deemed suitable for answering the study’s research question, which is explorative in nature. In addition, other researchers have suggested that a qualitative approach could be useful to gain insight into perceived benefits of BSC implementation (Al Sawalqa et al., 2011).

2.2. Data collection. The data used in this research paper were gathered as part of a larger research project on the BSC in Scandinavia (Madsen, 2011). A total of 61 semi-structured interviews with consultants and users of the BSC were conducted. A detailed break-down by informant type and country can be found in the table below.

Table 1. Break-down of informants by country and type

| Consultants | User organizations | Total |

Sweden | 7 | 5 | 12 |

Norway | 10 | 21 | 31 |

Denmark | 5 | 13 | 18 |

Total | 22 | 39 | 61 |

We utilized what can be characterized as a theoretical sample (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), meaning that the goal was to get theoretical variation. For instance, informants were recruited from both global and national consultancies, with varying service offerings and specializations, and from different types of user organizations. The informants were primarily identified using internet searches (e.g. Google), and by examining BSC-related websites, books, articles and conference material. Some informants were recruited via so-called ‘snowball sampling’ (Atkinson & Flint, 2001) where one informant refers the researcher to the next informant.

As can be seen from the table above, most of the informants were Norwegians, and the sample can therefore be said to be somewhat skewed towards Norwegian informants. For example, the total number of informants from Sweden is relatively low given that it is the largest country of the three. In addition, it was easier to recruit informants in Norway due to factors such as local university brand name, no language barriers and geographical considerations.

The length of the interviews was between 30 and 90 minutes, and covered several main topics including the adoption of the concept, the interpretation and implementation of the concept, and general experiences from using the concept. The interviews were fully transcribed and analyzed using an ‘issue- focused’ approach (Weiss, 1994), which allowed for comparing and contrasting across different informants and themes.

2.3. Potential issues. The interview data were gathered over the course of a nine-month period in 2004 and 2005, which was several years after height of the BSCs popularity and ‘hype’ in Scandinavia around the turn of the century (Ax & Bjornenak, 2005; Madsen, 2011). Most of the informants had several years of experience with the BSC, and were well past the initial adoption stage. As Malmi (2001) has pointed out, organizations which have recently adopted the BSC may still be in the ‘honeymoon’ stage where they may have difficulties in objectively evaluating the benefits of the newly adopted concept. In such cases the benefits may be overstated and difficulties downplayed. As a whole, it was relatively easy to get the informants to talk about what they perceived to be the benefits of the BSC. This is not surprising as several researchers have noted that getting organization to ‘open up’ about positive experiences is easier than have them talk about problems and negative experiences which may put them in a bad light (cf. Francis & Holloway, 2007, p. 177; Hoque, 2014, p. 49).

Our approach is explorative in nature, and has several limitations. For instance, the exposure to each organization was limited since only one interview was conducted within each organization. Typically the informant was a BSC project leader or manager. Hence, it is not possible to know whether these perceived problems were the actual problems experienced by the rest of the organization. We will come back to these issues towards the end of the paper.

3. Consultants’ perceptions of the benefits of BSC implementation

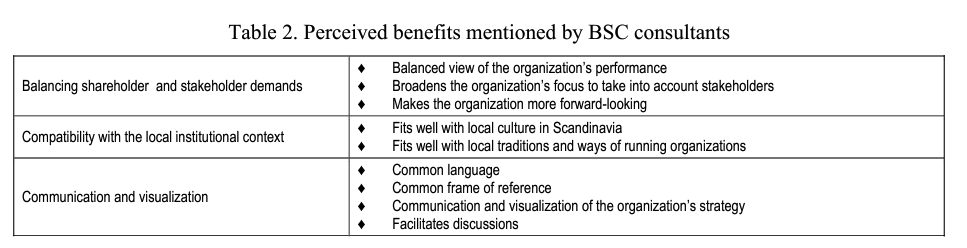

Table 1 shows the most important benefits mentioned by consultants. The perceived benefits are categorized in three topics: (1) balancing of shareholder and stakeholder demands, (2) compatibility with the Scandinavian culture, and (3) communication and visualization.

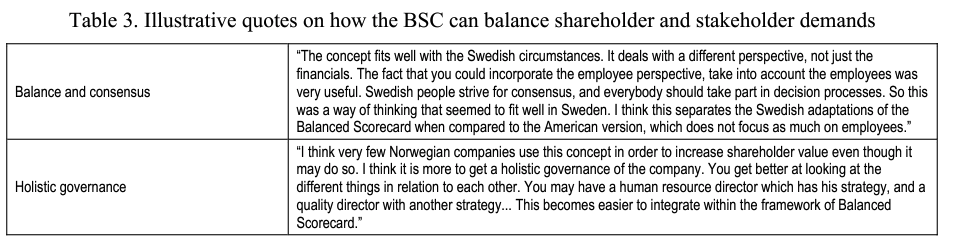

3.1. Balancing shareholder and stakeholder demands. One of the main issues mentioned by the consultants was that the BSC can be used to balance the demands of shareholders with the demands of other stakeholders. Several consultants pointed out that the BSC in Scandinavia is not necessarily used only to focus on shareholders. It provides a balanced view of the organization’s performance, and broadens a manager’s focus to take into account other issues than just financial aspects. As one consultant pointed out, the BSC gives managers a balanced view of their organization, which was not always the case pre-BSC. Informants pointed out that this type of stakeholder thinking is beneficial since organizations are dependent on all of its stakeholders and not just its owners.

The data show that the ‘balance’ is not only related to balancing the different perspectives or balancing financial and non-financial indicators. Instead, balance also entails balancing the demands of shareholders and other stakeholders, such as employees and unions. This can be seen in light of the stakeholder-oriented business culture in Scandinavia (Johanson, 2013; Näsi, 1995) and the consensus-oriented management style in Scandinavia (Grenness, 2003; Jonsson, 1996).

Finally, the BSC concept has in many ways shifted the thinking away from a sole focus on financial information to also take into account other non- financial indicators of performance, which makes organizations’ more forward-looking.

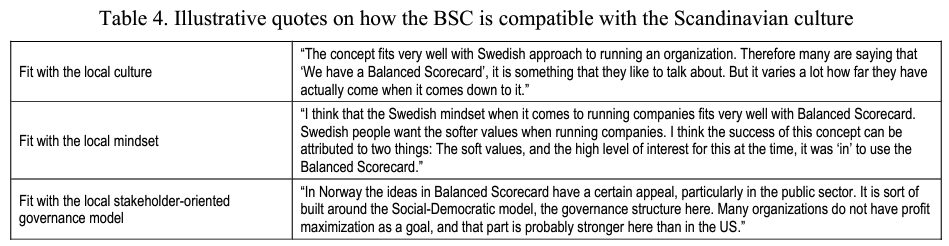

3.2. Compatibility with the Scandinavian culture. The second issue is related to the BSC concept’s compatibility with the Scandinavian institutional context. A common statement in the interviews was that the concept fits well with the local circumstances. Some consultants also mentioned that the notion of ‘balance’ makes the concept compatible with the business culture since it takes into account ‘softer values’ such as a focus on employees and other stakeholders. In addition, the fact that within the BSC concept there is room for other considerations than just ‘hard’ financial measures makes the concept fit the local mentality. More generally, most viewed it as a ‘good governance model’ for running an organization.

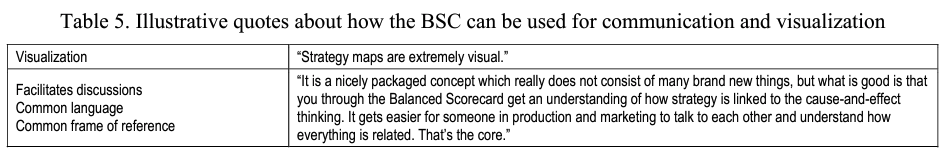

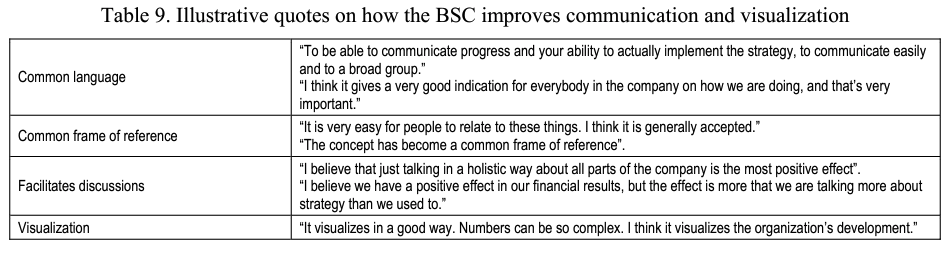

3.3. Communication and visualization. The third communication and visualization. The consultants main theme is related to how the BSC can be used for frequently mentioned how the concept can be useful in relation to communicating and visualizing the strategy in the organization. This is not surprising given how these aspects of the concepts are highlighted by the concept’s proponents in the normative literature (e.g. Kaplan & Norton, 2001; Kaplan & Norton, 2004, 2006). The consultants argued that the concept often makes it easier to communicate the strategy to the organization, something that was not always the case prior to the BSC. The BSC also provides a ‘common language’ and frame of reference, and can be a facilitator of useful discussions in the organization. In this regard, some consultants highlighted that the concept can facilitate useful discussions about strategies.

4. User organizations’ perceptions of benefits associated with BSC implementation

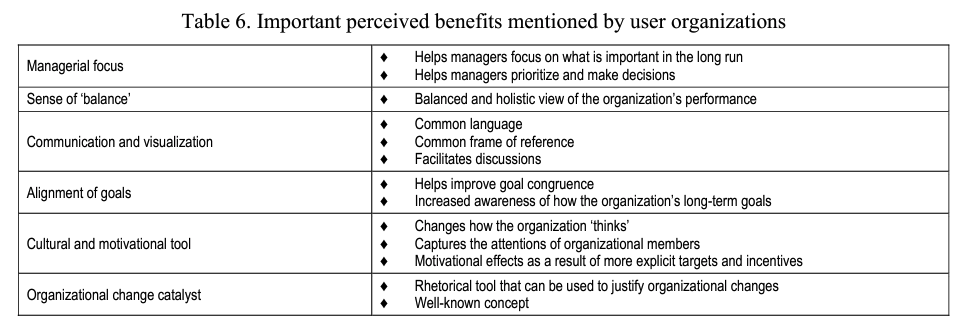

Table 6 shows the most important benefits mentioned by the user organizations. Six main issues emerged from the analysis of the interviews: (1) managerial ‘focus’ (2) the ‘balance’ provided by the BSC, (3) communication and visualization (4) alignment of goals, (5) cultural and motivational tool, and lastly (6) organizational change.

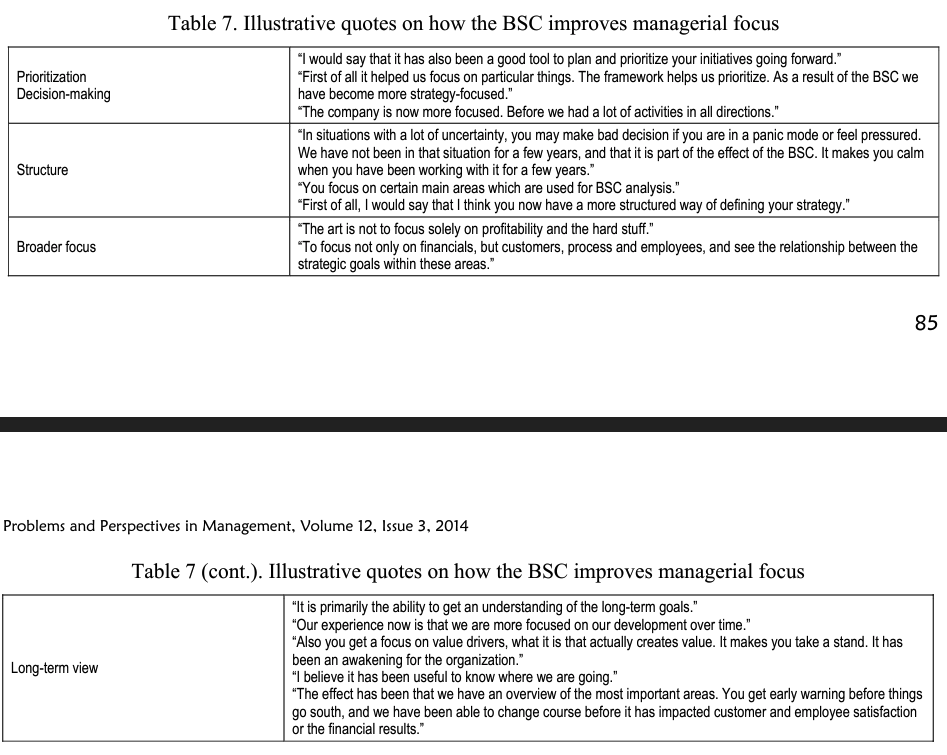

4.1. Managerial ‘focus’. The first theme is related to managerial focus. Several informants argued that the concept helps them focus on what is ‘important’. In other words, the concept assists managers and other organizational members in prioritizing and making decisions.

In addition, the BSC provides managers with some structure which may assist them in decision-making, particularly in situations with lots of uncertainty. As one informant pointed out, this helps him ‘keep calm’. Others pointed out that the four perspectives or ‘main areas’ in the BSC give managers a structure which is helpful in analysis. Some also mentioned that the concept provides a broader focus than just the financials and the ‘hard stuff. Finally, it provides managers with a long-term view, and makes them focus on value drivers, i.e. organizational capabilities and customer metrics indicate future performance. Some pointed out that the BSC helps them balance the short-term and the long-term considerations and goals. For instance, one can get ‘early warnings’ by keeping an eye on developments in non-financial indicators such as customer satisfaction.

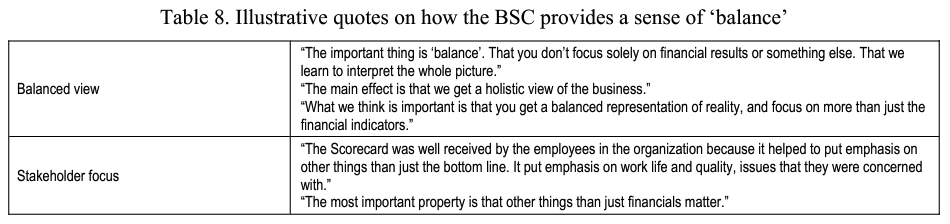

4.2. Sense of ‘balance’. The second theme is related to the sense of ‘balance’ that the BSC provides managers. A typical statement among the users was that the BSC gives the organization more ‘balance’ than they had prior to adoption and implementation. The more balanced view has helped to reduce the over-emphasis on financial measures. Many informants mentioned that their organizations traditionally had been dominated by financial indicators, and that the BSC with its emphasis on non-financial indicators helps shift the focus towards a more ‘holistic’ and balanced view of the organization’s performance.

Although it was mentioned less frequently than by the consultants, some managers also appreciated that the BSC helps them balance shareholder and stakeholder demands.

4.3. Communication and visualization. The third theme is related to communication and visualization. Some informants appreciated that the concept helps them to improve communication. For example, the BSC gives them a ‘common language’ and a frame of reference which can be useful to facilitate discussions.

Other informants pointed out that the BSC has certain visual aspects which are useful. For example, it was mentioned that BSC software packages with blinking lights (green, yellow and red) can provide managers with reassurance that they are on the right track. These benefits can partly be characterized as psychological in nature.

4.4. Goal alignment. The fourth theme is related to the goal alignment. Several informants mentioned that the concept helps to make sure that everyone in the organization works toward the same goals, i.e. what is referred to as goal congruence or ‘alignment’ in the BSC literature (cf. e.g. Kaplan & Norton, 2006).

Other informants pointed out that the BSC gives organizational members greater awareness of longterm goals. For example, employees see things differently than before, and have an improved understanding of how their activities affect the organization’s long-term goals.

Table 10. Illustrative quotes on how the BSC improves goal alignment

Improved goal congruence | “My impression is that the employees are more focused on the goals of this company... But 1 think that people now are more focused on what the goals are. So the system is a good tool for us in ensuring that everybody is pulling in the right direction”. “If you don’t have a scorecard, strategy could be something that only concerns the people on the top of the organization. So it becomes very difficult for people further down in the organization to relate to it. How they influence and contribute to the organization’s goals. The benefit of the BSC is that you break it all down.” |

Awareness of long-term goals | “Organizational members are now more aware of things like the pricing of products, and see this in a broader perspective than before, and how it influences the bank’s results. So the awareness has increased. 1 believe this opinion is shared by others as well.” “Now the employees concern themselves more with the company’s well-being that they did previously. It has without a doubt made us more like one firm." |

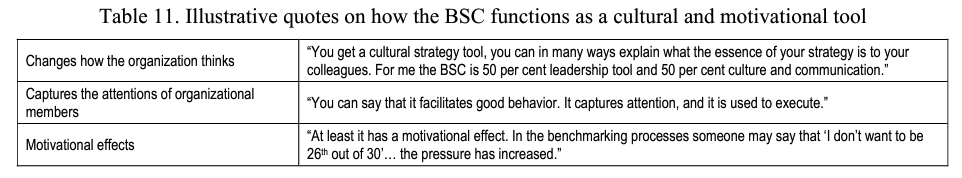

4.5. Cultural and motivational tool. The fifth theme is related to how the BSC can be used as a cultural and motivational tool. For example, some pointed out that the BSC can be cultural tools that can change how the organization ‘thinks’. Some informants claimed the main benefit of the concept is that it is a ‘cultural tool’ that can change how the organization operates and ‘thinks’, by explicitly focusing on the things that lead to better performance in the long run.

A related effect is that the BSC captures the attention of organizational members, which can be useful in goal-setting and for motivating employees. Others highlighted that the BSC can have certain motivational effects. Some informants emphasized how the concept can be a ‘motivational tool’. For example, the BSC can be used to set more explicit targets than before, and various types of incentives to encourage the right kind of behavior. This has traditionally been more difficult in the Scandinavian business culture, which generally is less accepting of objective measurement and individual rewards than is the case in Anglo-Saxon countries.

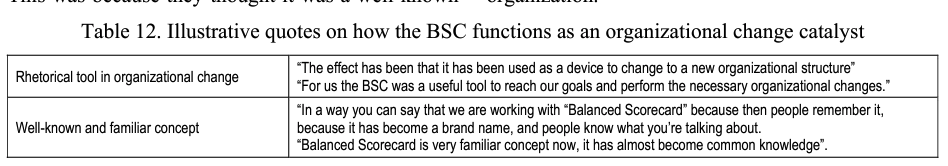

4.6. Organizational change catalyst. The final theme was related to how the BSC can be used as a catalyst in organizational change processes. Some users mentioned that using the BSC label can be a rhetorical tool in organizational change programs. This was because they thought it was a well-known and familiar concept. Since many people now have heard of the concept due to its popularity it can be useful to use the BSC label to argue that certain organizational changes are needed. In some cases, this can reduce resistance from the rest of the organization.

Discussion and conclusion

Main findings and contributions. The interviews showed that the both consultants and users of the concept perceive that the concept is useful. Many commented that the concept is what they consider to be ‘good practice’. The consultants highlighted that the BSC can be used to balance shareholder and stakeholder demands, the concept’s compatibility with local culture and business practices in Scandinavia, and how the BSC can be used to communicate and visualize. The user organizations highlighted that the concept helps them with managerial ‘focus’, gives them a sense of ‘balance’, helps with communication and visualization, aligns goals, is a cultural and motivational tool, and that the BSC label can be used to drive organizational change processes.

Both consultants and users mostly highlighted benefits related to social and organizational processes, and not the ‘technical’ aspects of the concept. Based on the interview data it seems that many of the benefits are related to more indirect organizational and behavioral effects.

We argue that the findings, although tentative and preliminary in nature, add to the BSC literature by providing new insights into the perceived benefits of the BSC. As we pointed out in the introduction, there is little extant research applications documenting positive experiences with implementation and applications of the BSC (Hoque, 2014, p. 49). These issues should be investigated more in-depth in future studies. Below we outline some possible approaches which could be followed in future research.

Limitations. Due to the paper’s explorative nature, it has several limitations. First of all, the benefits could be overstated by over-enthusiastic users. For example, the so-called ‘honeymoon period’ effect where new adopters are still ‘in love’ with their new management concept could play a role (cf. Mahni, 2001). However, we think this problem was reduced due to the fact that most of the informants had worked with BSC for a number of years and had acquired some ‘distance’ to the concept.

Another source of bias is that informants may report what they think the researcher wants to hear (Cook, Campbell & Day, 1979). Moreover, a BSC ‘champion’ or project manager is unlikely to admit that the implementation of their projects has fallen short of expectations and failed to deliver. This person could have a personal interest in painting a glossy portrait, and not put their organization in a bad light. There are several possible explanations for this type of behavior, e.g. to look good internally in the organization, but also to portray competence vis-ä-vis external parties. After all, some project leaders may ‘lose face’ if the new concept fails.

In the interviews the informants were asked to recollect past events. These recollections could be subject to different types of distortions and biases. For instance, ex-post rationalization (see e.g. Elster, 1989) could play a role as informants may justify the use of the concept by highlighting the benefits and downplaying negative experiences.

It should also be pointed out that the research design utilized has limitations. We were not able to study the relationship between different interpretations and expected perceived benefits. An organization using a well-fitted and customized version of the BSC, i.e. one which is complementing the organization’s strategy, is likely to be more successful (Braam & Nijssen, 2004; Davis & Albright, 2004; De Geuser et al., 2009).

It is likely that such organizations will experience different and more benefits as a result of their BSC usage. For example, as reported by Lucianetti (2010) the use of strategy maps may bring about many positive effects. This means that organizations that interpret the BSC narrowly as just a ‘performance measurement system’ (Lawrie & Cobbold, 2004; Speckbacher et al., 2003) may potentially experience fewer benefits.

Future research. The findings in this explorative paper could be investigated in more detail in future studies. In this paper we have focused on informants’ perceptions, which may not be reflective of the actual benefits. Future studies should study in more depth the link between perceived benefits and more objective measures of benefits.

For example, one way forward would be to utilize a more advanced research design which is better suited to deal with the complexity and interpretive space of management concepts. How do different interpretations and designs of BSCs influence the benefits that are experienced by users? Does the use of the more ‘advanced’ parts of the BSC concept such as strategy maps lead to more positive implementation experiences (cf. Lucianetti, 2010)?

Examples of more advanced research approaches would be in-depth case studies of organizations using the BSC, drawing on different types of microdata (see e.g. Madsen & Stenheim, 2013). For example, interviews with multiple informants at different levels of the organization could give insight into whether the perceptions of benefits are shared by the whole organization. It could also reduce the aforementioned potential problems with biases and selective perceptions on the part of a sole key informant, which is usually the ‘champion’ of the BSC concept in the organization.

Longitudinal studies would also be helpful, in order to better understand how different types of benefits are experienced at different stages of the implementation process. For example, it may be that it takes time for the positive effects of BSC implementation to surface. After all, in many organizations the implementation of a more ambitious version of the BSC could take several years (cf. e.g. Madsen & Stenheim, 2014).

Another possibility is to design multiple case studies. This would make it possible to compare and contrast the benefits (and problems) associated with the implementation of the BSC in different organizations. It would be useful to study in more detail what successful BSC implementers are doing, and find out why they are able to capitalize on the concept and extract beneficial effects. This could provide valuable practical insights to other organizations that are struggling with the implementation of the BSC (cf. Hoque, 2014).

As mentioned previously, there is still a lack of academic studies reporting on positive experiences with the BSC (Hoque, 2014, p. 49). Hence, there is great potential for future studies to provide more insight into what exactly it is that works for organizations in relation to the implementation of the BSC. Such research would be valuable not only for studying the implementation of management concepts such as the BSC in organizational praxis, but could also give practical pointers to organizations trying to extract benefits from the use of the BSC.

References

- Aidemark, L.G. (2001). The Meaning of Balanced Scorecards in the Health Care Organization, Financial Accountability & Management, 17 (1), pp. 23-40.

- Al Sawalqa, F., Holloway, D. & Alam, M. (2011). Balanced Scorecard implementation in Jordan: An initial analysis, International Journal of Electronic Business Management, 9 (3), pp. 196-210.

- Antonsen, Y. (2014). The downside of the Balanced Scorecard: A case study from Norway, Scandinavian Journal of Management, 30 (1), pp. 40-50.

- Atkinson, R. & Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies, Social Research Update, 33 (1), pp. 1-4.

- Ax, C. & Bjomenak, T. (2005). Bundling and diffusion of management accounting innovations - the case of the balanced scorecard in Sweden, Management Accounting Research, 16, pp. 1-20.

- Banchieri, L.C., Planas, F.C. & Rebull, M.V.S. (2011). What has been said, and what remains to be said, about the balanced scorecard? Proceedings of Rijeka Faculty of Economics, Journal of Economics and Business, 29 (1), pp. 155-192.

- Braam, G. (2012). Balanced Scorecard’s Interpretative Variability and Organizational Change. In C.-H. Quah & O.L. Dar (eds.), Business Dynamics in the 21st Century, InTech.

- Braam, G., Benders, J. & Heusinkveld, S. (2007). The balanced scorecard in the Netherlands: An analysis of its evolution using print-media indicators, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 20 (6), pp. 866-879.

- Braam, G., Heusinkveld, S., Benders, J. & Aubel, A. (2002). The reception pattern of the balanced scorecard: Accounting for interpretative viability, SOM-Theme G: Cross-contextual comparison of institutions and organisations, Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Nijmegen School of Management, University of Nijmegen.

- Braam, G. & Nijssen, E. (2004). Performance effects of using the Balanced Scorecard: a note on the Dutch experience, Long Range Planning, 37, pp. 335-349.

- Brudan, A. (2005). Balanced Scorecard typology and organisational impact, KM Online Journal of Knowledge Management, 2 (1).

- Cook, T.D., Campbell, D.T. & Day, A. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design & analysis issues for field settings, Boston, Houghton Mifflin.

- Davis, S. & Albright, T. (2004). An investigation of the effect of Balanced Scorecard implementation on financial performanc e, Management Accounting Research, 15 (2), pp. 135-153.

- De Geuser, F., Mooraj, S. & Oyon, D. (2009). Does the Balanced Scorecard Add Value? Empirical Evidence on its Effect on Performance, European Accounting Review, 18 (1), pp. 93-122.

- Dechow, N. (2012). The Balanced Scorecard-Subjects, Concept and Objects - A Commentary, Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 8 (4), pp. 511-527.

- Elster, J. (1989). Nuts and bolts for the social science, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Francis, G. & Holloway, J. (2007). What have we learned? Themes from the literature on best-practice benchmarking, International Journal of Management Reviews, 9 (3),pp. 171-189.

- Grenness, T. (2003). Scandinavian Managers on Scandinavian Management, International Journal of Value-Based Management, 16, pp. 9-21.

- Hansen, A. & Mouritsen, J. (2005). Strategies and Organizational Problems: Constructing Corporate Value and Coherences in Balanced Scorecard Processes, In C. S. Chapman (ed.), Controlling Strategy: Management, Accounting and Performance Measurement, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 125-150.

- Hoque, Z. (2014). 20 years of studies on the Balanced Scorecard: Trends, accomplishments, gaps and opportunities for future research, The British Accounting Review, 46 (1), pp. 33-59.

- Jarzabkowski, P., Balogun, J. & Seidl, D. (2007). Strategizing: The challenges of a practice perspective, Human Relations, 60 (1), pp. 5-27.

- Johanson, D. (2013). Beyond Budgeting from the American and Norwegian perspectives: the embeddedness of management models in corporate governance systems, In K. Kaarboe, P. Gooderham & H. Norreklit (eds.), Managing in Dynamic Business Environments: Between Control and Autonomy, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 69-91.

- Jönsson, S. (1996). Perspectives of Scandinavian Management, Göteborg, Bokforlaget BAS.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D P. (1992). The balanced scorecard - Measures that drive performance, Harvard Business Review, (January-February), pp. 71-79.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, DP. (2001). The strategy-focused organization; How balanced scorecard companies thrive in the new business environment, Boston, MA, Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D P. (2004). Strategy Maps: Converting intangible assets into tangible outcomes, Boston, MA, Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D P. (2006). Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Synergies, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, DP. (2008). Execution Premium: Linking Strategy to Operations for Competitive Advantage, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kasurinen, T. (2002). Exploring management accounting change: The case of balanced scorecard implementation, Management Accounting Research, (September), pp. 323-343.

- Lawrie, G. & Cobbold, I. (2004). Third-generation balanced scorecard: evolution of an effective strategic control tool, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 53 (7), pp. 611-623.

- Lucianetti, L. (2010). The impact of the strategy maps on balanced scorecard performance, International Journal of Business Performance Management, 12 (1), pp. 21-36.

- Lueg, R. & e Silva, A.L.C. (2013). When one size does not fit all: a literature review on the modifications of the balanced scorecard, Problems and Perspectives in Management, 11 (3), pp. 86-94.

- Madsen, D.0. (2011). The impact of the balanced scorecard in the Scandinavian countries: a comparative study of three national management fashion markets, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Norwegian School of Economics, Department of Strategy and Management, Bergen, Norway.

- Madsen, D.0. (2012). The Balanced Scorecard i Norge: En Studie av konseptets utviklingsforlop fra 1992 til 2011, Praktisk okonomi ogfmans, 4, pp. 55-66.

- Madsen, D.0. & Stenheim, T. (2013). Doing research on ‘management fashions’: methodological challenges and opportunities, Problems and Perspectives in Management, 11 (4), pp. 68-76.

- Madsen, D.0. & Stenheim, T. (2014). Perceived problems associated with the implementation of the balanced scorecard: evidence from Scandinavia, Problems and Perspectives in Management, 12 (1).

- Maisei, L.S. (2001). Performance Measurement practices Survey, New York, NY, American Institute of Public Accountants.

- Malmi, T. (2001). Balanced scorecards in Finnish companies: A research note, Management Accounting Research, 12, pp. 207-220.

- Modell, S. (2009). Bundling management control innovations: A field study of organisational experimenting with total quality management and the balanced scorecard, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 22, pp. 59-90.

- Modell, S. (2012). The Politics of the Balanced Scorecard, Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 8 (4), pp. 475-489.

- Nielsen, S. & Sorensen, R. (2004). Motives, diffusion and utilisation of the balanced scorecard in Denmark, International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, 1, pp. 103-124.

- Näsi, J. (1995). A Scandinavian Approach to Stakeholder Thinking: An Analysis of Its Theoretical and Practical Uses, 1964—1980, Understanding stakeholder thinking, Helsinki, Finland: LSR-Julkaisut Oy, pp. 97-115.

- Norreklit, H. (2003). The balanced scorecard: What is the score? A rhetorical analysis of the balanced scorecard, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28 (6), pp. 591-619.

- Norreklit, H., Jacobsen, M. & Mitchell, F. (2008). Pitfalls in using the balanced scorecard, Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 19, pp. 65-68.

- Norreklit, H., Norreklit, L., Mitchell, F. & Bjomenak, T. (2012). The rise of the balanced scorecard! Relevance regained? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 8 (4), pp. 490-510.

- Perkins, M., Grey, A. & Remmers, H. (2014). What do we really mean by “Balanced Scorecard?” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 63 (2), pp. 148-169.

- Rigby, D. & Bilodeau, B. (2009). Management Tools & Trends 2009, London, Bain & Company

- Rigby, D. & Bilodeau, B. (2011). Management Tools & Trends 2011, London, Bain & Company.

- Rigby, D. & Bilodeau, B. (2013). Management Tools & Trends 2013, London, Bain & Company.

- Silk, S. (1998). Automating the balanced scorecard, Management Accounting, May, pp. 38-40, pp. 42-44.

- Soderberg, M, Kalagnanam, S., Sheehan, N.T. & Vaidyanathan, G. (2011). When is a balanced scorecard a balanced scorecard? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 60 (7), pp. 688-708.

- Speckbacher, G., Bischof, J. & Pfeiffer, T. (2003). A descriptive analysis of the implementation of balanced scorecards in German-speaking countries, Management Accounting Research, December, pp. 361-388.

- Stemsrudhagen, J.I. (2004). The structure of balanced scorecards: empirical evidence from Norwegian manufacturing industry, In M.J. Epstein & J. Manzoni (eds.), Studies in Managerial and Financial Accounting: Performance Measurement and Managerial Control: Superior Organizational Performance, Oxford, Elsevier, pp. 303-321.

- Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques, SAGE Publications.

- Voelpel, S.C., Leibold, M. & Eckhoff, R.A. (2006). The tyranny of the Balanced Scorecard in the innovation economy, Journal of Intellectual Capital, 7 (1), pp. 43-60.

- Weiss, R.S. (1994). Learning from strangers: The art and method of qualitative interview studies, New York, Free Press.

- Whittington, R. (2003). The work of strategizing and organizing: for a practice perspective, Strategic organization, l,pp. 117-126.

- Wickramasinghe, D., Gooneratne, T. & Jayakody, J. (2007). Interest lost: the rise and fall of a balanced scorecard project in Sri Lanka, Advances in Public Interest Accounting, 13, pp. 237-271.