When one size does not fit all: a literature review on the modifications of the balanced scorecard

Published: Sept. 24, 2013

Latest article update: Dec. 8, 2022

Abstract

Robert Kaplan and David Norton emphasize that the four perspectives of their standard balanced scorecard (BSC) need to be adapted to the organizational context. Yet, we lack a coherent body of knowledge on these adaptations. 20 years after the implementation of the BSC, a literature review is warranted to investigate if and how the original BSC has been modified in practice. The authors conduct a systematic literature review of leading academic journals from 1992 to 2012 to identify and analyze the extant empirical evidence on the BSC. The authors find 117 empirical studies on the BSC, of which 27 deal with BSC-modifications. First, the authors conclude that the BSC-perspectives have been modified to match different industries, organizational levels, or functions (e.g., the public sector, information systems, supply chain management, corporate social responsibility, or incentive systems). Second, the authors use an established BSC classification, and argue that the BSC has also been modified in terms of its sophistication. This paper can only identify few examples where the BSC has become an incentive-relevant management system as imagined by Kaplan and Norton; many organizations stop at the level of a measurement system. On the one hand, this article demonstrates the versatility of the BSC and its perspectives as claimed by Kaplan and Norton. On the other hand, the lack of sophisticated implementations shed a critical light on the relevance of the BSC in practice

Keywords

Environment, Corporate social responsibility, public sector, literature review, balanced scorecard, organizational design, performance measurement system, supply chain management, information systems, implementation, performance evaluation, incentives

Introduction

Over the last 20 years, the balanced scorecard (BSC) has become one of the most popular management practices among both public and private organizations (Kaplan, 2012; Kaplan and Norton, 1992). It is a management system that aims at aligning an organization’s strategy with its planning and control systems. In order to achieve that, it derives its objectives, targets, key performance indicators (KPIs), and even action plans directly from an organization’s strategy map. The KPIs of the BSC differ from traditional performance measurement systems (PMSs) as they combine financial and non-financial, as well as leading and lagging KPIs. The original model of the BSC prescribed four perspectives (financial, customer, internal processes, learning and growth) for which appropriate KPIs had to be defined (Kaplan and Norton, 1992). Later, Kaplan & Norton (1996, p. 34) corrected this, stating that these perspectives should only be used as a template and needed to be adjusted to organizational context.

However, there is no consistent body of knowledge that could help to understand if and how these BSC- modifications have been achieved in practice. These insights would be of high relevance as the naive implementation of generic, decontextualized management practices is detrimental to organizational performance (Chenhall, 2003; Lueg and Nprreklit, 2013. 2012). To address this gap, we address the research question: How has the balanced scorecard been modified in organizational practice?

To answer this question, we conduct a systematic literature review of empirical evidence on the BSC, that has been published in leading academic and practitioner journals from the implementation of the BSC in 1992 to 2012. In total, we identify 117 empirical studies on the BSC, of which 27 deal with BSC-modifications.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 1 introduces our theoretical framework. Section 2 explains our methodology and literature search. Section 3 analyzes the relevant articles. We discuss the limitations and contributions of our findings in the final section.

1. Theoretical concepts

We focus on BSC-modifications in two main areas: changes in BSC-perspectives and changes in BSC- sophisfieafion.

1.1. BSC perspective. In the beginning, Kaplan & Norton (1992) introduced the four BSC-perspectives as a general recommendation for implementation: the financial perspective covers how success is measured by shareholders. The customer perspective determines how the organization creates value for its customers. Internal business processes explains at which processes the organization must excel in order

to satisfy its customers and shareholders. The learning and growth perspective addresses the capabilities and information systems necessary to improve processes and customer relationships. Later, Kaplan & Norton (1996, p. 34) began emphasizing the need to adjust the BSC to organizational context:

“The four perspectives of the BSC have been found to be robust across a wide variety of companies and industries. But the four perspectives should be considered a template, not a strait jacket. No mathematical theorem exists that four perspectives are both necessary and sufficient. ”

Kaplan and Norton have then provided some anecdotal evidence how the BSC could be modified. First, they suggest adding or exchanging perspec-tives. Second, they suggest changing the importance of the perspectives, e.g., assigning less importance to the financial perspective in education or public services (Atkinson et al., 2011). Over the years, Kaplan and Norton (2001, 2004,2006,2008) have also made more suggestions of how the BSC can be better applied, e.g., for the corporate headquarter, or compensation purposes.

Despite its popularity, many critics have raised concerns against the BSC. Among the most prominent, Nprreklit (2000) challenges the mechanistic assumptions of the BSC, which assert that cause-and-effect relationships can be determined exante by top-down management. Later, she also shows that the BSC’s perspectives are outdated versions of the much older ‘Profit Impact of Market Strategy’ study (Lueg and Nprreklit, 2012). Moreover, Nprreklit (2003) deconstructs the rhetoric of the BSC’s authors, claiming that the popularity of the BSC is based in persuasive rhetoric rather than in solid academic argumentation. As a seminal empirical work, Inner & Larcker (2003) document a case where a by-the-book-implemented BSC is abandoned by an organization due to subjectivity of top management evaluators, and insensitivity for middle managers’ values. In a literature review, Zimmerman (2001, p. 424) similarly criticizes the BSC’s assumption that employees will alter their personal motivations only because of a new management control system:

“[...] the balanced scorecard [...] assume[s] that agents will enthusiastically adopt the new approach because it promises to maximize firm value. [...] This “Field of Dreams” (if you build it, they will come) approach ignores employee self-interest. ”

1.2. BSC types. Other researchers classify BSC- modifications not by (the weight of) BSC- perspectives, but by the sophistication of the BSC- implementation (e.g., Mahni, 2001). Speckbacher et al. (2003) conduct an empirical study and uncover that BSCs differ most distinctly in their scope. Based on their data from German-speaking countries, they suggest another classification of BSC-modifications:

- BSC type 1: The organization groups strategic (non)-financial measures or objectives according to a number of perspectives.

- BSC type 2: A BSC type 1 that describes the organization’s strategy with sequential cause- and-effect logic (still a measurement system).

- BSC type 3: A BSC type 2 that additionally contains targets and action plans that are linked to managers’ incentives (management system).

According to Kaplan & Norton (1996, p. 34), only the BSC type 3 is a full BSC that affects organizational performance. Our literature review will also accommodate for this sort of BSC-modifications as a benchmark for the definition of section 1.1.

2. Methodology

We conducted our literature review in four steps. First, we conducted our surveys in the databases ABI Inform, EBSCO, and ScienceDirect instead of limiting ourselves to a pre-selected set of journals. A search for ‘balance scorecard’ in the timeframe 1992 to 2012 resulted in 1,031 hits. Second, we kept only the 315 empirical articles to understand practices in the field. Third, we selected only those articles that were published in academic or practitioner journals of the highest quality, i.e., a minimum two star rating from the Association of Business Schools (Harvey et al., 2010). We also went through these articles’ bibliographies to uncover further relevant sources. This left us with 117 high qualify, empirical papers on the BSC. In a fourth step, we scanned abstracts, key-words, and titles of these articles, as we only aimed at the topic of BSC-modifications. We also included articles where the names of the perspectives were changed, even if we found out later that the content remained the same. This way, we did not omit any relevant literature. We ended up with a dataset of 27 articles, which we will review in the following section.

3. Analysis of the empirical literature

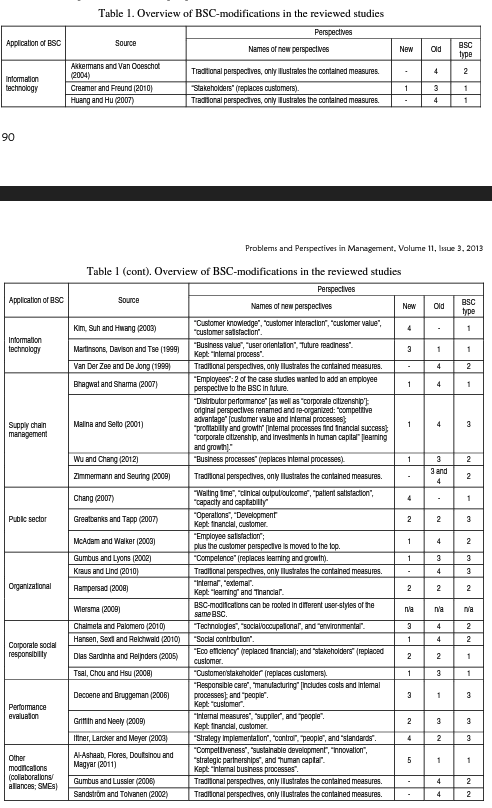

This review structures the literature for the reader by a framework. We followed established approaches in the management literature to draft such a framework (Katsikeas et al., 2000; Lueg, 2008; Lueg and Schäffer, 2010). We first studied the conceptual literature and established preliminary categories that should cover the most important fields of interest on BSC modifications. In a second step, we read all the sources we identified as relevant for this review. While reading the sources, we analyzed them for patterns that could help us to improve the preliminary framework of our analysis. Based on this, we adjusted our preliminary categories. We agreed on seven distinctive categories that should help the reader to get a good overview (ГГ, supply chain management, public sector, organizational levels, corporate social responsibility, performance eva-luation and other modifications). We provide a systematic overview of the articles’ characteristics at the end of this section.

3.1. Information technology. The difficulties of implementing information technologies (IT) and assessing their performance have been acknowledged by scholars (Lueg and Lu, 2012, 2013; Martinsons et al., 1999). Therefore, finding means to overcome these issues and to improve the management of IT systems has been a research focus. The BSC appears to be an effective tool to align and integrate ГГ and business strategies.

Huang and Hu (2007) show how to align IT capabilities and activities with business objectives and business requirements using the BSC. They illustrate measures to adjust the traditional perspctives.

Van Der Zee and De Jong (1999) demonstrate how the BSC helps managers and IT engineers to develop a common language. The authors even suggest that BSC can advance beyond a strategic management system and help to align organizational values and different cultures across departments.

Martinsons et al. (1999) follow the development of a BSC for information systems (IS) that measures and evaluates the following perspectives: business value, user orientation, internal process, and future readiness. Based on case study evidence, they suggest that the IS BSC could be used as a “[...] foundation for a strategic IS management system.”

Kim, Suh and Hwang (2003) provide an example of such an application by investigating an implementation of Customer Relationship Management (CRM). In that case, the BSC could be used to replace the traditional financial measuring systems as well as all traditional BSC-perspectives in an iterative process. The new system used the (mostly) non- financial perspectives of customer knowledge, customer interaction, customer value, and customer satisfaction. These were deemed more relevant than purely financial ones in the CRM setting.

Alternatively, IT tools can also optimize the components of the BSC in terms of precision or accessibility. Creamer and Freund (2010) showcase the adaptation of a BSC through machine learning methods. These helped defining the structure of a board-BSC for corporate governance purposes. One outcome was that the traditional customer perspective was replaced by the new perspective of stakeholders. According to Creamer and Freund (2010, p. 384), the improved BSC was:

“...able to forecast corporate performance, select the most important variables, establish relationships among these variables, define a target for each variable to optimize corporate performance, and build a board strategy map and a board BSC”.

This allowed managers to focus on the most important strategic issues and to delegate target setting to a semiautomated planning system.

Likewise, Akkermans and Van Oorschot (2004) show empirically that system dynamics (SD) modeling and simulation methods can effectively address problems with the quality of BSC-measures during the development process of the BSC.

Due to the limited scope of these IT-BSCs, we could not identify any BSC types 3.

3.2. Supply chain management The case study of Malina and Selto (2001) describes a BSC that focuses on the distribution channels of the US company. Managers merged the original 4 perspectives into 3 to suit the specific context in the following way: (1) competitive advantage related to customer value and internal processes; (2) profitability and growth depicted internal processes find financial success; (3) corporate citizenship was added and put together with investments in human capital, which both related to the learning and growth perspective. A completely new perspective was (4) distributor performance. While the authors found the BSC to be effective to align operations with strategy, they also noted tension between top and middle managers on the evaluation, control and communication mechanisms that came with the BSC. As to SCM-BSCs, this is the only BSC type 3 we could identify.

Bhagwat and Sharma (2007) follow the implementation of a BSC in an SME in India. While the BSC was focused on SCM and kept the original 4 perspectives, the value of the article lies in the elaborate suggestion of specific, SCM-related metrics for the BSC. This framework could be used as a strategic SCM evaluation tool to monitor and guide projects and general performance improvement efforts.

Zimmermann and Seuring (2009) conduct two case studies in the chemical and automotive industry where producers and retailers developed joint BSCs along their supply chains. Their article provides detailed insights into the strategy maps, perspectives, as well as a detailed account of the characteristics of used KPIs of these two BSCs. Their first case is also an example where the crucial learning and development perspective has been eliminated from the BSC, a step against which Kaplan and Norton (1996) generally warn. As it turned out, the companies dropped their plans to implement BSC types 2 due to the high maintenance costs.

Wu and Chang (2012) use survey data from 127 organizations to map the diffusion process of the BSC in SCM. Their study suggests that the four generic perspectives are widespread, but several organizations have modified the BSC’s measures and perspectives. Specifically, Wu and Chang (2012) propose that in SCM, the more externally focused perspective business process should replace internal processes in the SCM context.

3.3. Public sector. Kaplan (1999) acknowledges the difficulties to measure performance in the public sector. Due to the non-financial nature of many of its objectives, he suggests the BSC as a PMS. However, public organizations seem to struggle more than private ones in implementing the BSC.

Chang (2007) documents how the BSC was applied by the UK National Healthcare System to assess the performance of hospitals and to inform the public about this. The four original perspectives of the BSC were replaced by national targets related to waiting time, clinical output/outcome, patient satisfaction and capacity and capability. The main focus of the performance measures was on waiting time, and the importance of feedback from the patient was overlooked. As the choice of most BSC-measures was subject to political power, this led to a misleading rating system. Furthermore, the case demonstrated that the desire of politicians for shortterm and easily understandable measures might have hindered a more rigorous, long-term public sector reform.

Greatbanks and Tapp (2007) provide an example on how the BSC helped to improve service quality at the Customer Service Agency (CSA) in New Zealand. Each scorecard was built up from the strategic, financial, operational, customer and development measures with respect to each department and for each concerned employee. However, we alert that the BSC was only implemented at a sub-division level, which limits conclusions on the strategic alignment. Yet, the BSC was used to establish an incentive system for employees; for this reason, we classify this BSC as the only BSC type 3 in the public sector context.

McAdam and Walker (2003) investigate a BSC in local UK government. The authors provide a framework for implementing and managing strategy at all levels of public management and to link objectives, initiatives and measures to an organization’s strategy. In the case study, the perspective of employee satisfaction was added, and the importance of the customer perspective was prioritized. The overall results were mixed, but mainly positive in relation to the three main objectives of the public sector (Kaplan, 1999): create value, minimize costs and develop ongoing support and commitment from its funding authority.

3.4. Organizational levels: corporate and personal BSCs. In the beginnings of the BSC, Kaplan and Norton (1992; 1993a; 1993b) only related the BSC to the level of strategic business units (SBUs). They first mentioned the corporate BSC (CBSC) in 1996 (Kaplan and Norton, 1996), but did not develop its conceptual foundations until recently (Kaplan and Norton, 2008). Their main claim is that the CBSC orchestrates the SBUs and exploits their synergies.

Kraus and Lind (2010) investigate 8 of the largest Swedish organizations. They conclude that the CBSC had little impact on the effectiveness of corporate control since was mostly financially oriented.

Gumbus and Lyons (2002) explain how Philips Electronics overcame this limitation by implementing several SBU-BSCs connected by the corporate strategy. This BSC had three levels (strategy, operations, business unit), and the extension to a fourth level was planned (employee). Three traditional perspectives were kept. Only learning and growth was replaced by competence, as it also comprised the notion of leadership. Since this is the only BSC that links results to compensation, it is the only BSC type 3 in this field.

There are also two investigations of the BSC at the level of the actor. Wiersma (2009) finds the way 224 individual managers across 19 Dutch organizations use the BSC (decision-making/rationalizing, coordination, self-monitoring) depends on the context (evaluation style, competing controls, receptiveness to new information). This indicates that even if an organization has 1 BSC, its notion differs with every user. Rampersad (2008) develops a personal BSC to increase an actor’s efforts for the organization. It still incorporates the financial and learning perspectives. He adds an internal perspective (relating to the actors health and mental state) as well as an external perspective (relations to other actors).

3.5. Corporate social responsibility. When incorporating social and environmental performance measures, the BSC can address organizational sustainability (Lueg et al., 2013a; Songini and Pis- toni, 2012).

As an example, Dias-Sardinha and Reijnders (2005) document how large Portuguese organizations address social and environmental performance. 2 out of the 4 perspectives of the BSC were changed to adapt to serve this purpose: the financial perspective was replaced by eco efficiency (compliance and pollution management), and the customer perspective by stakeholders. The authors reported several problems with the BSC implantation, such as the dearth of relative performance measures, the eclectic nature of non-financial indicators, as well as the predominance of financials in industrial organizations.

Tsai, Chou and Hsu (2008) demonstrate how to use a sustainability BSC to evaluate socially responsible investments. For that, they suggest replacing the customer perspective with a broader stakeholder/ customer perspective.

Chahneta and Palomero (2010) investigate the use of the BSC for sustainability in 16 organizations. Besides adjusting the traditional 4 perspectives, they suggest adding 3 new perspectives: technologies, social/occupational, and environmental.

Hansen et al. (2010) follow the implementation of a community focused BSC by Merck in Thailand. They report that a fifth perspective was added to the 4 traditional ones (social contribution).

We criticize that none of the studies can explain how the organizations have linked their CSR- intentions to the results from the BSC, e.g., by using incentive systems. Therefore, we cannot classify any of these CSR-BSCs as a BSC type 3.

3.6. Performance evaluation. Kaplan and Norton (1996, p. 34) see the link from the BSC to incentive systems as the final step to a fully implemented BSC, which corresponds to the understanding of researchers that classify the BSC by sophistication (Lueg, 2010; Malmi, 2001; Speckbacher et al., 2003). Since all of the BSCs in this section consider performance evaluation, they are all BSC types 3.

Inner et al. (2003) investigate the use of a BSC for compensation in financial services. They find that the traditional perspectives of the BSC were not sufficient for this: only the perspectives financial and customer were kept, and the four new perspectives on strategy implementation, customer, control, people, and standards were added. The authors report that the BSC was finally discarded in favor of a revenuebased incentive system due to problems of the BSC with overreliance of lagging, financial measures, as well as dysfunctional subjectivity of superiors in evaluations.

Also Decoene and Bruggeman (2006) are critical. They document a BSC-modification of a Danish plastics manufacturer that keeps the customer perspective and adds the following perspectives: responsible care; manufacturing [includes costs and internal processes]; and people. They conclude that the top-down compensation plan lacked strategic alignment. Hence, it did motivate actors to increase organizational performance.

Griffith and Neely (2009) use a quasi-experiment to investigate incentives and branch performance in the UK. The included BSC perspectives are the traditional perspectives financial and customer, the newly added are internal measures, people and supplier. The authors conclude that the success of BSC- incentives varied across branches, mostly depending on the experience the middle managers had to respond to the new incentives.

3.7. Other modifications: collaborations, alliances, and SMEs. The BSC was further modified for diverse other purposes. Sandstrom and Toivanen (2002) demonstrate how the BSC replaces schedules and budgets for engineers in the product development and design of a manufacturer. The merit of the paper lies in showing different measures for the traditional 4 perspectives. Al-Ashaab et al. (2011) conduct two case studies and illustrate how the BSC can also be used in collaborative, inter-organizational settings. Only the internal business processes perspective was kept for that. The newly added perspectives included competitiveness, sustainable development, innovation, strategic partnerships, and human capital. Gumbus and Lussier (2006) use three case studies to illustrate how the BSC and its traditional four perspectives can be adjusted to small- and mediumsized organizations. Due to the limited scope of these IT-BSCs, we could not identify any BSC types 3. Table 1 summarizes our analysis.

4.Discussion

4.1. Contributions. This article addresses the question how the Balanced Scorecard has been modified in organizational practice. We find that organizations modify the BSC in two main ways: (1) by adapting the perspectives and the pertinent objectives and KPIs to their specific needs (Kaplan and Norton, 1996), and (2) by choosing the BSC type (sophistication) that fits its purpose(Speckbacher et al., 2003). Our findings make several contributions to the extant literature.

First, we can somehow confirm the claim of Kaplan and Norton (1996) that the BSC is versatile and can be used across different industries, functions or hierarchies. The empirical evidence suggests that it is not always necessary to invent new perspectives - that might lead to information overload or lack of focus - to adjust a BSC to a new context. Rather, a contextbound selection of objectives and KPIs can already lead to an appropriate modification. Yet, we alert practitioners that the implementations in some fields were constantly subject to severe problems, e.g., in the public sector, or for incentive systems.

Second, we find that the empirical evidence across the many identified fields does not offer a clear pattern of modifications. Neither were all modifycations successful. Therefore, we cannot offer advice to practice on the ideal modifications. Nevertheless, this literature review offers a compre-hensive overview of the state of the art of BSC-modifications and can thereby help researchers and practitioners to quickly identify the most relevant studies.

Third, we follow Nprreklit et al. (2012) and challenge the notion of Kaplan (2012) that the BSC is highly relevant in practice: out of the 27 reviewed articles, only 6 (22%) report that the BSC has been fully implemented as a type 3 (Speckbacher et al., 2003). This is relatively low compared to the high rates of implementations of similar systems, such as Valuebased Management (Burkert and Lueg, 2013). If so many organizations have a BSC type 1 or 2 - that Kaplan and Norton (1996, p. 217) describe as nonperformance enhancing - then something else must drive organizational performance, and the BSC is only a placebo. Since its implementation is, however, time-consuming and expensive, managers should be very clear about its purpose before adopting and modifying it.

4.2. Limitations. A main limitation of this review is that we limited ourselves to high quality academic and practitioner journals. We may have possibly overlooked valuable studies from books or conference presentations. Another limitation of this article is that the analysis of the modifications was limited to the changes in the types and in the perspectives of the BSC. For instance, the review could have been structured by the different ways that actors use the same type of BSCs.

4.3. Future research. Future research topics could expand on our contributions. First, analytical and conceptual researchers could attempt to suggest a general pattern of BSC-modifications that empirical researchers could use as a benchmark. Second, future studies should generally incorporate success measures of the BSC-modifications that are comparable across studies in order to see how ‘relevant’ the popular BSC actually is for organizations in the field. Third, researchers could take a closer look at the often neglected learning and growth perspective, that accounts for intangible assets (cf. Lueg et al., 2013b).

Conclusion

To conclude, this article aimed at reviewing the empirical literature on BSC-modifications. We could show that the BSC is very versatile and has been applied across many industries, functions and hierarchies (IT, SCM, public sector, organizational levels, CSR, perfor-mance evaluations, alliances, or SMEs). Yet, the performance effects of these modifications remain open issues.

References

- Akkermans, H.A., K.E. Van Oorschot (2004). Relevance assumed: a case study of Balanced Scorecard development using system dynamics, Journal of the Operational Research Society, 56, pp. 931-941.

- Al-Ashaab, A., M. Flores, A. Doultsinou, A. Magyar (2011). A Balanced scorecard for measuring the impact of industry-university collaboration, Production Planning & Control, 22, pp. 554-570.

- Atkinson, A.A., R.S. Kaplan, E.M. Matsumura, S.M. Young (2011). Management Accounting, International Edition, 6th ed. Pearson, New Jersey, NJ.

- Bhagwat, R., M.K. Sharma (2007). Performance measurement of supply chain management: a balanced scorecard approach, Computers & Industrial Engineering, 53, pp. 43-62.

- Burkert, M., R. Lueg (2013). Differences in the sophistication of Value-based Management - The role of top executives, Management Accounting Research, 24, pp. 3-22.

- Chalmeta, R., S. Palomero (2010). Methodological proposal for business sustainability management by means of the Balanced Scorecard, Journal of the Operational Research Society, 62, pp. 1344-1356.

- Chang, L.-C. (2007). The NHS performance assessment framework as a Balanced Scorecard approach: limitations and implications, International Journal of Public Sector Management, 20, pp. 101-117.

- Chenhall, R.H. (2003). Management control systems design within its organizational context: findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28, pp. 127-168.

- Creamer, G., Freund Y. (2010). Learning a board Balanced Scorecard to improve corporate performance, Decision Support Systems, 49, pp. 365-385.

- Decoene, V., Bruggeman W. (2006). Strategic alignment and middle-level managers’ motivation in a Balanced Scorecard setting, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26, pp. 429-448.

- Dias-Sardinha, I., Reijnders L. (2005). Evaluating environmental and social performance of large Portuguese companies: a Balanced Scorecard approach, Business Strategy and the Environment, 14, pp. 73-91.

- Greatbanks, R., Tapp D. (2007). The impact of Balanced Scorecards in a public sector environment: empirical evidence from Dunedin City Council, New Zealand, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 27, pp. 846-873.

- Griffith, R., Neely A. (2009). Performance pay and managerial experience in multitask teams: evidence from within a firm, Journal of Labor Economics, 27, pp. 49-82.

- Gumbus, A., Lussier R.N. (2006). Entrepreneurs use a Balanced Scorecard to translate strategy into performance measures, Journal of Small Business Management, 44, pp. 407-425.

- Gumbus, A., Lyons B. (2002). The Balanced Scorecard at Philips Electronics, Strategic Finance, 84, pp. 45-49.

- Hansen, E.G., M. Sextl, R. Reichwald (2010). Managing strategic alliances through a community-enabled balanced scorecard: the case of Merck Ltd, Thailand, Business Strategy and the Environment, 19, pp. 387-399.

- Harvey, C., A. Kelly, H. Morris, M. Rowlinson (2010). Academic Journal Quality Guide, The Association of Business Schools, London.

- Huang, C.D., Q. Hu (2007). Achieving ГГ-business strategic alignment via enterprise-wide implementation of Balanced Scorecards, Information Systems Management, 24, pp. 173-184.

- Ittner, C.D., D.F. Larcker, M.W. Meyer (2003). Subjectivity and the weighting of performance measures: evidence from a Balanced Scorecard, The Accounting Review, 78, pp. 725-758.

- Kaplan, R.S. (1999). The Balanced Scorecard for Public Sector Organisations, Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Kaplan, R.S. (2012). The Balanced Scorecard: comments on Balanced Scorecard commentaries, Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 8, pp. 539-545.

- Kaplan, R.S., D.P. Norton (1992). The Balanced Scorecard - Measures that drive performance, Harvard Business Review, 70, pp. 71-79.

- Kaplan, R.S., D.P. Norton (1993a). Implementing the Balanced Scorecard at FMC corporation: An interview with Larry D. Brady, Harvard Business Review, 71, pp. 143-147.

- Kaplan, R.S., D.P. Norton (1993b). Putting the Balanced Scorecard to work, The Performance Measurement, Management and Appraisal Sourcebook, 66-79.

- Kaplan, R.S., D.P. Norton (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

- Kaplan, R.S., D.P. Norton (2001). The Strategy-Focussed Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

- Kaplan, R.S., D.P. Norton (2004). Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets Into Tangible Outcomes, Harvard Business Press, Boston, MA.

- Kaplan, R.S., D.P. Norton (2006). Alignment: Using the Balanced Scorecard to Create Corporate Synergies, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

- Kaplan, R.S., D.P. Norton (2008). The Execution Premium: Linking Strategy to Operations for Competitive Advantage, Harvard Business Press, Boston, MA.

- Katsikeas, C.S., L.C. Leonidou, N.A. Morgan (2000). Firm-level export performance assessment: review, evaluation, and development, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28, pp. 493-511.

- Kim, J., E. Suh, H. Hwang (2003). A model for evaluating the effectiveness of CRM using the Balanced Scorecard, Journal of interactive Marketing, 17, pp. 5-19.

- Kraus, K., J. Lind (2010). The impact of the corporate Balanced Scorecard on corporate control - A research note, Management Accounting Research, 21, pp. 265-277.

- Lueg, R. (2008). Value-based Management: Empirical Evidence on its Determinants and Performance Effects, WHU Otto Beisheim School of Management, Vallendar.

- Lueg, R. (2010). Shareholder Value und Value Based Management - Wie steuern die HDAX-Konzeme? Zeitschrift für Controlling, 22, pp. 337-344.

- Lueg, R., S.N. Clemmensen, M.M. Pedersen (2013). The role of corporate sustainability in a low-cost business model - A case study in the Scandinavian fashion industry, Business Strategy and the Environment (forthcoming)..

- Lueg, R., S. Lu (2012). Improving efficiency in budgeting - An interventionist approach to spreadsheet accuracy testing, Problems and Perspectives in Management, 10, pp. 32-41.

- Lueg, R., S. Lu (2013). How to improve efficiency in budgeting - The case of business intelligence in SMEs, European Journal of Management, (forthcoming).

- Lueg, R., Nedergaard, L., Svendgaard, S. (2013b). The use of intellectual capital as a competitive tool: a Danish case study, International Journal of Management, 30, No. 2, pp. 217-231.

- Lueg, R., H. Nprreklit (2012). Performance measurement systems - Beyond generic strategic actions // In: Mitchell, F., Nprreklit, H., Jakobsen, M. (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Cost Management. Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 342-359.

- Lueg, R., U. Schäffer (2010). Assessing empirical research on value-based management: guidelines for improved hypothesis testing, Journal für Betriebswirtschaft, 60, pp. 1-47.

- Malina, M.A., F.H. Selto (2001). Communicating and controlling strategy: an empirical study of the effectiveness of the Balanced Scorecard, Journal of Management Accounting Research, 13, pp. 47-90.

- Malmi, T. (2001). Balanced Scorecards in Finnish companies: a research note, Management Accounting Research, 12, pp. 207-220.

- Martinsons, M., R. Davison, D. Tse (1999). The balanced scorecard: a foundation for the strategic management of information systems, Decision Support Systems, 25, pp. 71-88.

- McAdam, R., T. Walker (2003). An inquiry into Balanced Scorecards within best value implementation in UK local government, Public Administration, 81, pp. 873-892.

- Nprreklit, H. (2000). The balance on the Balanced Scorecard: a critical analysis of some of its assumptions, Management Accounting Research, 11, pp. 65-88.

- N0rreklit, H. (2003). The Balanced Scorecard: what is the score? A rhetorical analysis of the Balanced Scorecard, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28, pp. 591-619.

- Nprreklit, H., L. Nprreklit, F. Mitchell, T. Bjpmenak (2012). The rise of the Balanced Scorecard - Relevance regained? Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 8, pp. 490-510.

- Rampersad, H.K. (2008). The way to a highly engaged and happy workforce based on the Personal Balanced Scorecard, Total Quality Management, 19, pp. 11-27.

- Sandstrom, J., J. Toivanen (2002). The problem of managing product development engineers: can the Balanced Scorecard be an answer? International Journal of Production Economics, 78, pp. 79-90.

- Songini, L., A. Pistoni (2012). Accounting, auditing and control for sustainability, Management Accounting Research, 23, pp. 202-204.

- Speckbacher, G., J. Bischof, T. Pfeiffer (2003). A descriptive analysis on the implementation of Balanced Scorecards in German-speaking countries, Management Accounting Research, 14, pp. 361-388.

- Tsai, W., W. Chou, W. Hsu (2008). The sustainability Balanced Scorecard as a framework for selecting socially responsible investment: an effective MCDM model, Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60, pp. 1396-1410.

- Van Der Zee, J., B. De Jong (1999). Alignment is not enough: integrating business and information technology management with the balanced business scorecard, Journal of Management Information Systems, 16, pp. 137-156.

- Wiersma, E. (2009). For which purposes do managers use Balanced Scorecards? An empirical study, Management Accounting Research, 20, pp. 239-251.

- Wu, I.-L., C.-H. Chang (2012). Using the Balanced Scorecard in assessing the performance of e-SCM diffusion: a multi-stage perspective, Decision Support Systems.

- Zimmerman, J.L. (2001). Conjectures regarding empirical managerial accounting research, Journal of Accounting & Economics, 32, pp. 411-427.

- Zimmermann, K., S. Seuring (2009). Two case studies on developing, implementing and evaluating a Balanced Scorecard in distribution channel dyads, International Journal of Logistics: Research and Applications, 12, pp. 63-81.