Does board composition have an impact on CSR reporting?

Published: June 7, 2017

Latest article update: Dec. 10, 2022

Abstract

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting plays a key role in management control, particularly in light of the increased demand for non-financial reporting after the f inancial crisis of 2008–2009. This literature review evaluates 47 empirical studies that concentrate on the influence of several board composition variables on the quantity and quality of CSR reporting. The author briefly introduces the research framework that underpins current empirical studies in this field. This is followed by a discussion of the main variables of board composition: (1) committees (audit and CSR committees), (2) board independence, (3) board expertise, (4) CEO duality, (5) board diversity (gender and foreign diversity), (6) board activity, and (7) board size. The author, then, summarizes the key findings, discusses the limitations of the existing research and offers useful recommendations for researchers, firm practice and regulators

Keywords

Corporate social responsibility, board of directors, board composition, corporate governance, board expertise, board diversity, committees, CSR reporting, board independence

INTRODUCTION

Society’s increasing awareness of environmental, social and governance issues has contributed to a transformation in the way business is conducted (Kolk and van Tulder, 2010; Seuring and Mueller, 2008), particularly in terms of external reporting systems. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a modern management concept has been rapidly increasing by public interest entities (PIEs). As the term “CSR” is heterogeneously used in research literature, our interpretation of CSR deals with the triple bottom line concept and the business case model, indicating that economic, environmental and social aspects are equal within stakeholder management (Carroll, 1999). CSR within a company indicates that companies are responsible not only for maximizing profits, but also for recognizing the needs of their relevant stakeholders such as employees, customers, etc. Successful CSR management should lead to voluntary CSR reporting as a complement to classical financial accounting (e.g., financial statements, group/management reports). CSR disclosures may be included in the annual report or be separated to a “stand-alone” CSR report (Rao and Tilt, 2016). A CSR report covers environmental, social and governance (ESC) issues in line with widely recognized CSR reporting standards, e.g., the guidelines of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). CSR reporting is a key information tool of PIEs to increase stakeholder relations, especially about the firms’ ESG performance (Murphy and McGrath, 2013). In the end, if CSR management has been conducted successfully and is included in CSR reporting, a positive impact on CSR performance may be the consequence. On the one hand, the usefulness of CSR reports has led stakeholders to demand even greater decision usefulness of CSR reporting (Moneva et al., 2006; Ramus and Montiel, 2005). On the other hand, literature states that information overload and greenwashing as current practice lower the validity of CSR reporting (Mahoney et al., 2013). This has resulted in an increased significance of CSR reporting in business practices while also making this topic a focal point of recent empirical CSR research. Empirical studies examining the factors of influence that affect CSR reporting and the potential implications have primarily been conducted on the board system (Dienes et al., 2016; Malik, 2015). Given the lack of mandatory CSR reporting in most legal systems, management has extensive freedom of discretion and flexibility when it comes to how these companies portray themselves in their CSR reports. This means that each individual company can influence their CSR reports and (selectively) manipulate its informational value to suit its information policy (Darus et al., 2014).

After the financial crisis of 2008-2009, (international standard-setters (e.g., the European Commission) initiated several reform measures to strengthen the quality of board composition (e.g., board diversity), on the one hand, and CSR reporting, on the other hand. The adoption of the Directive 2014/95/EU in the European member states has great implications for board diversity and CSR reporting (Federation of European Accountants, 2015; Johansen, 2016; Monciardini, 2016), as specific PIEs must prepare a non-financial declaration and a diversity report as part of the corporate governance statement. The relationship between board composition and CSR reporting is also a growing topic of empirical research from an international perspective (Jain and Jamali, 2016; Malik, 2015). Prior empirical research has focused on the link between board composition variables such as internal corporate governance and measures of CSR reporting and, over the last few years, a growing number of studies have been carried out that have incorporated a statistical examination of the impact of specific board composition variables (e.g., gender diversity) on the quality and quantity of CSR reports (Sharif and Rashid, 2014). But the results of these studies are characterized by a high level of heterogeneity.

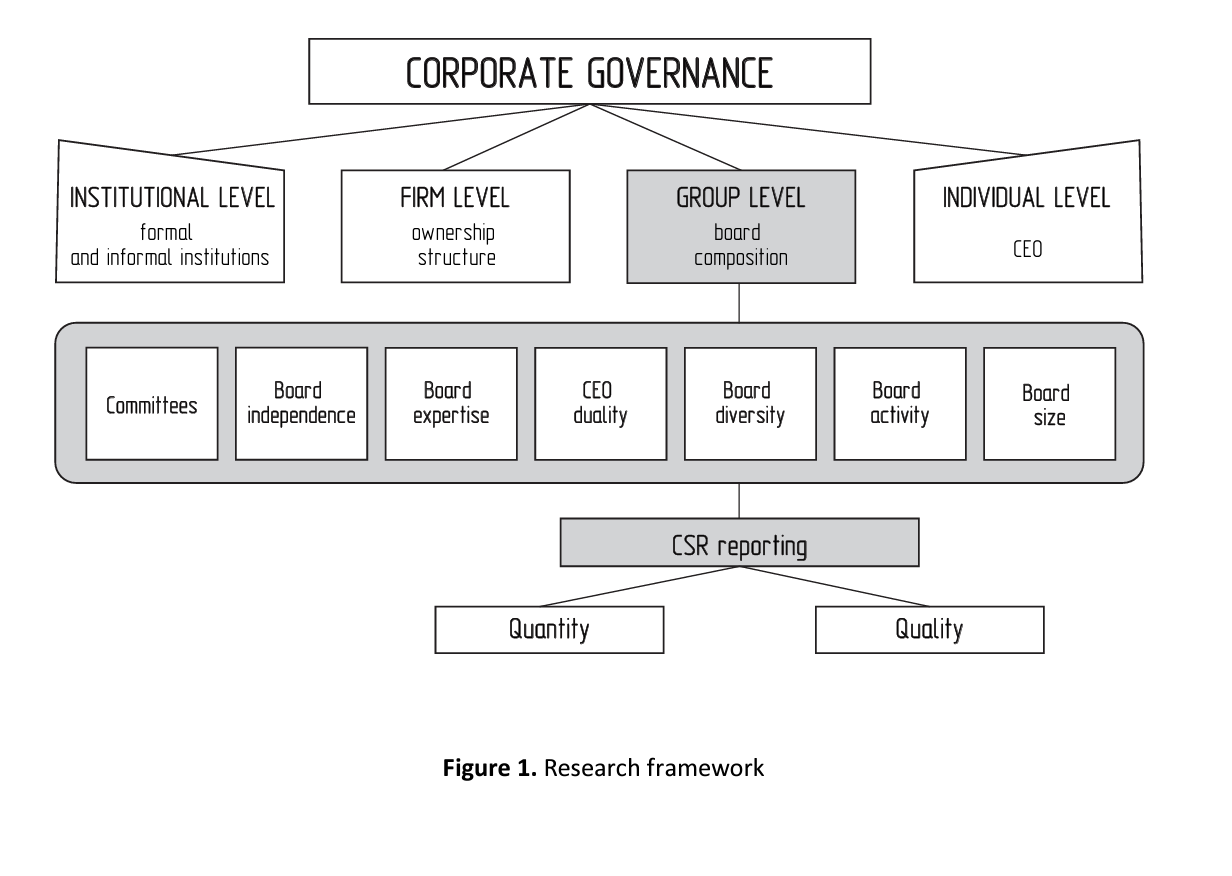

In this literature review of empirical-quantitative studies, we concentrate on board composition as a key aspect of internal corporate governance and note that external corporate governance (e.g., shareholder concentration) can also be important in influencing the quantity and quality of CSR reporting. According to the underlying research framework of our literature review, CSR reporting may be mainly influenced by the following variables of board composition: (1) committees (audit and CSR), (2) board independence, (3) board expertise, (4) CEO duality, (5) board diversity (gender and internationality), (6) board size, and (7) board activity.

The objective of this analysis is to evaluate the existing empirical studies on the impact of board composition on CSR reporting. We see a major benefit of linking the two topics board composition and CSR reporting in one literature review in view of the following aspects. Current empirical research, regulatory and practical literature states that there is an interaction between board composition variables and CSR reporting measures that can be expressed by the term “sustainable corporate governance” (Paetzmann, 2016). Successful stakeholder management, in turn, depends on efficient board composition and decision-useful CSR reporting and, ultimately, can lead to stakeholder trust. As researchers, regulators and companies are more and more aware of this relationship, there is little knowledge about the current state of empirical research on that topic. Insofar, our literature review contributes to the present literature, as we analyze, for the first time, which board composition variables are mainly used in international research and which variables are statistically related to CSR reporting measures.

Our literature review is based on the methodology of vote counting of significances (Light and Smith, 1971). A quantitative literature analysis in the form of vote counting focuses on the significant findings and their respective signs, but ignores the specific coefficient values. The underlying primary studies are assigned the expressions significant positive (+) and significant negative (-). In comparison to former narrative literature reviews that are related to broader corporate governance determinants or CSR output variables, our methodology can lead to a clear result in which board composition variables are significantly linked with CSR reporting. We are aware of the limitations of vote counting. The methodology of a quantitative meta-analysis, which gets more and more attractive in recent empirical corporate governance and CSR research, is not useful in this situation because of the heterogeneous board composition variables in our sample. Furthermore, the amount of studies that relates to one specific composition attribute is too low for a meta-analysis yet.

Our literature review makes several contributions to the present literature, because it synthesizes a number of major new insights from the existing literature and offers a new and rich discussion of future avenues of research. Our review is aimed at researchers, regulators, and practitioners alike. It provides starting points for future research activities in terms of investigating the link between board composition and CSR reporting variables. We portray which board composition variables are commonly used in empirical research, explain the restrictions of these items and recommend additional variables that should be reflected. The findings also provide an important impetus for the analysis and development of recent CSR and corporate governance regulations. As already stated, several board composition variables, especially board diversity, are currently regulated as a useful instrument in order to strengthen CSR reporting (see Directive 2014/95/EU). Our review will contribute to this regulatory discussion by showing possible outcomes of this reform measure. Finally, we would like to motivate corporate practice to recognize the interactions of board composition and CSR reporting activities as key elements of stakeholder relations.

This review is structured as follows. First, the research framework is presented from a theoretical and empirical perspective, followed by an appraisal of the studies’ empirical findings. In so doing, we first present the methodology followed by a detailed analysis of empirical studies that relate to CSR reporting quantity and quality. Finally, the review considers the limitations of existing empirical research and makes useful recommendations for future research, stressing some practical and regulatory implications.

1. BOARD COMPOSITION AND CSR REPORTING FRAMEWORK

For the purposes of this literature review, a research framework is useful to contextualize the main strengths of the existing research (see Figure 1 in Appendix). We develop a research framework before providing a summary of empirical studies. The intention of our research framework is to accumulate and integrate heterogeneous board composition variables linked with CSR reporting in order to support researchers, regulators and practitioners in this field. Researchers, regulators and practitioners should become aware of the main determinants of CSR reporting in current empirical research. Insofar, the implementation of a research framework may help researchers by identifying research gaps, helping practitioners to increase CSR reporting and regulators in current reform activities on these topics. With this in mind, the link between board composition and CSR reporting is given emphasis throughout, even though such an explicit research framework does not exist in the literature so far. We have relied on a broad research structure suggested by Jain and Jamali (2016). An analysis of multilevel corporate governance mechanisms implies that there are institutional-level, firm-level, group-level, and individual-level corporate governance mechanisms. In this review, we concentrate on the group level of corporate governance mechanisms and the following variables of board composition: (1) committees (esp., audit and CSR), (2) board independence, (3) board expertise, (4) CEO duality, (5) board diversity (esp., gender and foreign), (6) board size, and (7) board activity.

2. REVIEW OF RESEARCH ON BOARD COMPOSITION AND CSR REPORTING

2.1. Methods

The empirical studies included in this literature review were chosen by comparing international databases (Web of Science, Google Scholar, SSRN, EBSCO, ScienceDirect) along with several other libraries. To this end, a targeted search was conducted for the keywords “corporate (social) responsibility reporting”, “corporate (social) responsibility disclosure”, “CSR reporting”, “CSR disclosures”, “sustainability disclosure”, as well as “sustainability reporting”, “environmental reporting”, and “social reporting”. In parallel, the search was either broadened by the addition of the broader term “corporate governance” or narrowed by the addition of specific variables (e.g., gender diversity). In the further course of our literature review, contributions were examined for the suitability of their study design. We did not limit our selection to a specific country. A temporal limitation was not useful given our limited number of studies; we focused only on archival studies as the dominant research method in this field. For reasons of quality assurance, only the contributions published in international (English) journals with double-blind review were included. As of the end of January 2017, 64 studies corresponding to the selection criteria mentioned above were identified. Due to definitional differences, this set of studies was narrowed further. The present literature review is based on the definition of CSR reporting as a voluntary report, as part of the annual report or a stand-alone report that covers environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues in line with widely recognized CSR reporting standards, e.g., the guidelines of the GRI. Insofar, only studies that analyze CSR reports with these main ESG issues and not parts of it (e.g., Carbon Disclosures) are included. As we restricted our literature review to archival studies, only public interest entities (PIEs), e.g., capital market oriented companies and/or financial institutions) are included. While some literature reviews and empirical studies match CSR reporting and CSR performance together, we decided to have a clear separation. CSR performance is usually measured by certain overall rankings (e.g., by the KLD database, Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters). In our framework, CSR reporting represents one indicator that influences CSR performance. Insofar, the two terms CSR reporting and CSR performance should not be used as synonyms. We excluded those studies that concentrate on CSR performance as the dependent variable, because our aim was to analyze the impact of board composition on CSR reporting. Furthermore, we do not include empirical studies on the link between board composition on integrated reporting because of the different concept. Integrated reporting, according to the framework of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC, 2013), represents the principle-based integrated thinking approach (Eccles and Krzus, 2015; Mio, 2016; Rowbottom and Locke, 2016; Simnett and Huggins, 2015). In contrast to this, CSR reporting according to the famous GRI guidelines is casuistic following the triple bottom line concept and indicates a clear stakeholder approach. After missing studies in view of our research topic, we present a final sample of 47 empirical studies. With regard to CSR reporting measures, quantity and quality are separated in our literature review. CSR reporting quantity represents the easiest way of modelling as just counting the words, sentences or pages of the CSR disclosures or checking the existence of certain CSR items. The authors perform a criteria-based content analysis of CSR reports by means of a scoring mechanism (disclosure index). In view of the huge discussion of information overload and greenwashing of CSR reporting, the validity of CSR reporting quantity as dependent variable is restricted, but dominant in current empirical research. The minority of the included studies methodically focus on CSR reporting quality, as they rely on external disclosure quality ratings or perform a 5- or 7-point Likert scale with regard to CSR disclosure principles.

The following overview of current research on board composition and CSR reporting variables allows one to systematically map and analyze the current international body of research within our framework. A quantitative literature analysis in the form of vote counting (Light and Smith, 1971) helps to focus on the most significant findings and their respective indicators, but ignores the specific coefficient values. The underlying primary studies have been assigned the expressions significantly positive (+), negative (-), and no impact (+/-). In comparison to other narrative literature reviews on broader topics (e.g., total corporate governance or CSR), we clearly stress the link between board composition and CSR reporting. Vote counting is a very common method in corporate governance and CSR research, but not conducted in this research topic yet. We are aware of the fact that vote counting is a limited method for synthesizing evidence from multiple evaluations, which involves comparing the number of significances. Vote counting does not take into account the quality of the studies, the size of the samples, or the size of the effect. These limitations are decreased by a quantitative meta-analysis. Our board composition variables are too heterogeneous to conduct a meta-analysis. A meta-analysis for one board variable is also not possible in view of the restricted amount of studies.

Our review makes several contributions to earlier work, because it synthesizes a number of major new insights from the literature and offers a rich discussion of future avenues of research. In contrast to former reviews on related topics (Dienes et al., 2016; Jain and Jamali, 2016; Rao and Tilt, 2016a; Malik, 2015; Elsakit and Worthington, 2014; Hahn and Kühnen, 2013; Fifka, 2012; Guan and Noronha, 2011), we provide a clear structure for empirical research, concentrate on board composition and CSR reporting, and present the main results of the empirical research according to a vote counting methodology. Guan and Noronha (2011) only analyzed Chinese research studies without any focus on corporate governance issues and other countries. Filka's review (2012) was organized by countries or regions without a clear focus on board composition. In their review, Hahn and Kühnen (2013) stressed that governance issues at the levels of company and country are key research gaps in empirical CSR reporting research, but did not analyze the relevant studies in detail. The review by Elsakit and Worthington (2014) lacked a sound theoretical foundation and a research framework. The authors only presented selective studies on corporate governance issues, namely, multiple directorships, board independence, and foreign diversity. Malik (2015) took a broader view of CSR activities, but CSR reporting was only part of his analysis. We already explained that it is not useful to match CSR performance and CSR reporting studies in one literature review as Malik (2015) does because of the different concepts. Malik (2015) only gave an overview of selective research studies on boards and ownership structure. The more recent review by Dienes et al. (2016) analyzed the “drivers” of sustainability reporting. The authors classified the relevant board composition variables in their review as “corporate governance structure” together with other determinants (firm size, profitability, capital structure, media visibility, ownership structure, firm age). This method of organization was not entirely useful, because board composition is only one part of corporate governance to bear in mind. The review by Rao and Tilt (2016a) also adopted a much broader view on CSR, so that both board composition and CSR reporting were only two among other elements in their review. They also integrated studies that analyzed voluntary disclosure, which meant that other kinds of stakeholder communication were mentioned as well. So far, Jain and Jamali (2016) have presented the best research structure for broad multilevel corporate governance mechanisms, and we rely on this for our own analysis. Their study took a broader look at every corporate governance mechanism, as well as a matching of CSR performance and CSR reporting. In contrast to the aforementioned literature reviews on broader analysis concepts, we are interested in the link between board composition (no other corporate governance topics) and CSR reporting (no other CSR topics) in view of the current political, practical and research discussion.

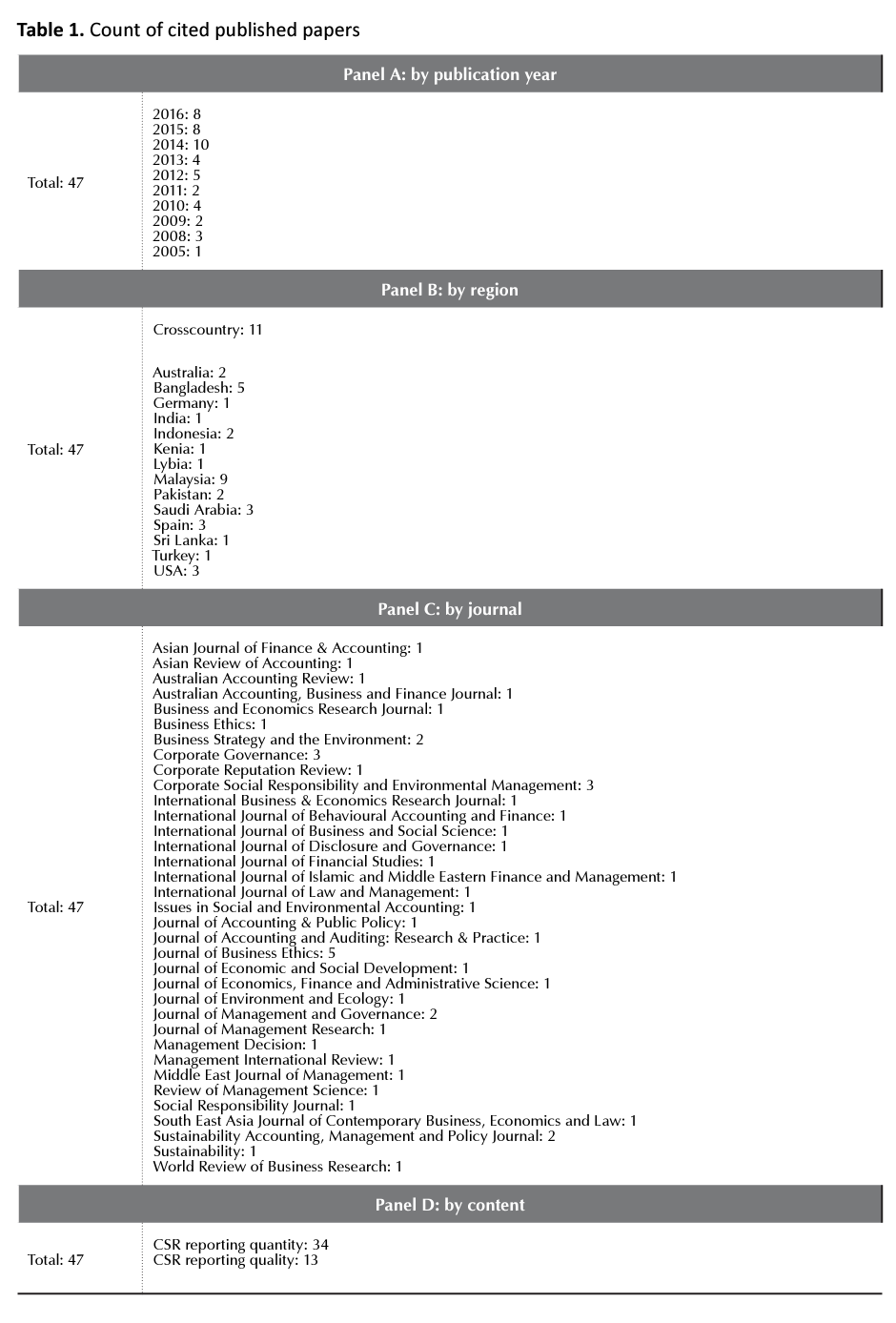

Table 1 (see Appendix) provides an overview of the number of included contributions per line of research, the year of publication, the regions examined, the journals in which the contributions were published, and the content. The studies were all published or prepared within the last 11 years (2005-2016) with a clear increase in recent years. In contrast to much of the empirical corporate governance research, very few studies analyzed the US-American and the European market. Developing countries are very attractive for sample selection (e.g., Bangladesh, Malaysia, Pakistan). Cross-country studies were not common. Many of the research findings were published in accounting journals, corporate governance and ethics journals. A commonly used medium for this type of research is the Journal of Business Ethics, in which six studies were published, whereas three publications were found in Corporate Governance. Most of the studies (34) concentrate on CSR reporting quantity because of the easy measurement.

2.2. Quantity of CSR reporting

The majority of research analyzed uses measures of CSR reporting quantity, e.g., counting the words or sentences, or checklists with a simple unweighted coding of zero (no disclosure of a special item) and one (disclosure of a special item). This strategy is dominant because of the easy practice and the limitation of bias problems and subjectivity. Many studies rely on Haniffa and Cooke (2005) as one of the first empirical studies wordwide that recognizes the link between board composition and CSR reporting (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Muttakin et al., 2016; Rao and Tilt, 2016; Benomran et al., 2015; Sundarasen et al., 2016; Kilic et al., 2015; Majjed et al., 2015; Muttakin and Subramaniam, 2015; Sharif and Rashid, 2014; Ali and Atan, 2013; Khan et al., 2013; Said et al., 2009). Furthermore, other CSR disclosure quantity measures with regard to CSR reporting guidelines or external ratings (ISO 26000: Habbash, 2016; GRI: Handajani et al., 2014; Faisal et al., 2013; Prado- Lorenzo et al., 2012; Michelon, 2011; KPMG: Fernandez-Feijoo et al., 2014), individual scores without a focus on a special framework (Bukair and Rahman, 2015; Das et al., 2015; Michelon and Parbonetti, 2012; added by an external validation (Rouf, 2011; Khan, 2010; Li et al., 2010; Siregar and Bachtiar, 2010; Barako and Brown, 2008; Lim et al., 2008; Haniffa and Cooke, 2005) or just word counting without a content analysis (Darus et al., 2015; Janggu et al., 2014) can be found. Finally, also the existence of a CSR reporting as a dummy variable is included (Shamil et al., 2014; Herda et al., 2013; Dilling, 2010; Kent and Monem, 2008).

The most included board composition variables are existence of an audit committee (Khan et al., 2013; Rouf, 2011; Said et al., 2009), existence of a CSR committee (Michelon and Parbonetti, 2012; Michelon, 2011; Kent and Monem, 2008), existence of a CSR or corporate governance committee (Dilling, 2010), board independence (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Habbash, 2016; Rao and Tilt, 2016; Benomran et al., 2015; Sundarasen et al., 2015; Bukair and Rahman, 2015; Darus et al., 2015; Das et al., 2015; Kilic et al., 2015; Majjed et al., 2015; Muttakin and Subramaniam, 2015; Handajani et al., 2014; Janggu et al., 2014; Shamil et al., 2014; Sharif and Rashid, 2014; Ali and Atan, 2013; Herda et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2013; Faisal et al., 2012; Michelon and Parbonetti, 2012; Prado- Lorenzo et al., 2012; Rouf, 2011; Khan, 2010; Li et al., 2010; Said et al., 2009; Barako and Brown, 2008; Kent and Monem, 2008; Lim et al., 2008; Haniffa and Cooke, 2005), CSR expertise of the board (Michelon and Parbonetti, 2012), the combination of fully independent board members and at least one financial expert (Habbash, 2016), CEO duality model (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Habbash, 2016; Benomran et al., 2015; Sundarasen et al., 2016; Bukair and Rahman, 2015; Das et al., 2015; Muttakin and Subramaniam, 2015; Shamil et al., 2014; Ali and Atan, 2013; Khan et al., 2013; Michelon and Parbonetti, 2012; Li et al., 2012; Said et al., 2009; Kent and Monem, 2008; Lim et al., 2008), CEO power as a complement of duality, ownership, tenure and family members (Muttakin et al., 2016), gender diversity (Rao and Tilt, 2016; Sundarasen et al., 2016; Darus et al., 2015; Kilic et al., 2015; Majjed et al., 2015; Fernandez-Feijoo et al., 2014; Handajani et al., 2014; Shamil et al., 2014; Khan, 2010; Barako and Brown, 2008), foreign diversity (Majjed et al., 2015; Janggu et al., 2014; Sharif and Rashid, 2014; Khan, 2010; Barako and Brown, 2008; Haniffa and Cooke, 2005), board activity (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Dilling, 2010; Kent and Monem, 2008; related to the audit committee: Habbash, 2016) and board size (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Benomran et al., 2015; Bukair and Rahman, 2015; Darus et al., 2015; Das et al., 2015; Kilic et al., 2015; Majjed et al., 2015; Handajani et al., 2014; Janggu et al., 2014; Shamil et al., 2014; Ali and Atan, 2013; Michelon and Parbonetti, 2012; Dilling, 2010; Siregar and Bachtiar, 2010; Said et al., 2009; Kent and Monem, 2008).

Recent research has dealt less and less with audit committees owing to increasing regulation (e.g., in the EU or in the USA). From an international perspective, this regulation has led to limited flexibility in the discrete establishment of an audit committee - especially in developed countries. At the same time, this has also led to growing research interest in this area in developing countries (e.g., Bangladesh, Malaysia). Therefore, a positive impact on the implementation of audit committees and CSR reporting quantity was found by Khan et al. (2013) (Bangladesh), Rouf (2011) (Bangladesh) and Said et al. (2009) (Malaysia). Rouf (2011) is the only study in this context with a check of their disclosure score by external experts. With regard to the voluntary implementation of CSR committees, Michelon (2011) found a positive impact on CSR reporting in a multinational study of mainly US and European companies. Kent and Monem (2008) stated a positive relationship between CSR committees and the existence of CSR reporting in an Australian setting. As CSR committees can incentive the board of directors to a higher extent with regard to CSR reporting, this composition variable seems to be relevant.

In contrast to this, the empirical results of board independence are mixed for developed (USA, Spain) and developing countries (e.g., Malysia, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, BRIC countries, Kenya). In the banking industry in Bangladesh, Turkey, Pakistan and Kenia, Das et al. (2015), Khan (2010), Kilic et al. (2015), Sharif and Rashid (2014) and Barako and Brown (2008) stated a positive relationship between board independence and CSR reporting. Also, outside the financial industry in India, Malaysia and Bangladesh and the BRIC countries, Muttakin and Subramaniam (2015), Ali and Atan (2013), Lim et al. (2008), Khan et al. (2013), Rouf (2011) and Li et al. (2010) found that board independence increases CSR reporting quantity. In contrast to this, Sundarasen et al. (2016) and Haniffa and Cooke (2005) found a negative relationship for Malaysian companies. The results are also mixed for developed countries. According to Herda et al. (2013), board independence contributes to the implementation of a CSR reporting in 500 US companies. Prado-Lorenzo et al. (2012) focused on GRI based-CSR reporting and came to the reverse link for Spanish companies.

In contrast to the huge research interest to board independence, board expertise is not very common in recent board composition and CSR reporting research. One possible reason for this research gap might be the hard examination of the CVs of the board members and the coding. However, expertise, e.g., CSR and/or financial expertise, seems to be most relevant to realize an adequate CSR reporting strategy. In our included studies, only Michelon and Parbonetti (2012) came to the result that CSR expertise on the board is positively related to CSR reporting for 114 (US and Europe companies).

As already mentioned, CEO duality is a very common board composition variable and also dominant in practice. However, it remains unclear whether CEO duality is linked with CSR reporting, as better firm knowledge contrasts higher conflict of interests. Insofar, it is not surprising that significant results in the included studies are rare. Interestingly, only negative impacts of CEO duality on CSR reporting are stated (Muttakin and Subramaniam (2015); Shamil et al. (2014) for Sri Lanka; Li et al. (2010) for the BRIC countries and Lim et al. (2008) for Malaysia).

In view of the huge discussion of gender diversity from an international perspective, current empirical research recognizes this diversity variable and only secondarily other dimensions (e.g., foreign diversity). In line with other output factors of gender diversity research (e.g., CSR performance), the results are heterogeneous. For the banking industry in Turkey and Kenya, Kilic et al. (2015) and Barako and Brown (2008) found a positive impact of gender diversity on CSR reporting. For other industries in Australia and Malaysia, Rao and Tilt (2016) and Sundarasen et al. (2016) also stated a positive relationship. The same results were shown by Fernandez-Feijoo et al. (2014) for mainly US, European and Australian companies. However, Handajani et al. (2014) and Shamil et al. (2014) found a negative significance in Indonesia and Sri Lanka. With regard to foreign diversity, Khan (2010) found a positive impact on CSR reporting in Bangladesh.

Measuring the frequency of board or committee meetings as a proxy for board activity is a common practice in empirical research with an unclear relationship to CSR reporting. As stated before, the board might influence the amount of meetings without being more effective. Insofar, it is not surprising that only one study (Kent and Monem, 2008) for the Australian market came to the conclusion that the meeting frequency of the audit committee relates to the existence of a CSR report. In line with board activity, also, board size is a very common board composition variable with unclear

impact on CSR reporting from a theoretical perspective as indicated. However, the significant results are homogenous in the included studies for developing countries. Excluding the financial industry, a positive relationship is found by Alotaibi and Hussainey (2016) (Saudi Arabia), Benomran et al. (2015) (Lybia), Darus et al. (2015), Janggu et al. (2014) and Ali and Atan (2013) in Malaysia, Majjed et al. (2015) (Pakistan), Handajani et al. (2014) and Siregar and Bachtiar (2010) (Indonesia) and Shamil et al. (2014) (Sri Lanka).

2.4. Quality of CSR reporting

Empirical research on CSR reporting quality is not very common in view of the increased resources of analysis and the bias problem. As there is a lack of objective quality measures for CSR reporting, a variety of methods was used in former studies. Some researchers rely on external ratings to increase the reliability of the measures. The analysis of Dienes and Veite (2016) was based on the German “IÖW (!!!Author decrypt)/future score” with the weighted characteristics of social, ecological, society, mang agement and general requirements. Fernandez- Gago et al. (2016) also chose an independent quality score (“Observatorio Score”), which rates the compliance with UN norms. Giannaraakis et al. (2014) used the Bloomberg disclosure score, which rates the environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosures of PIEs.

Other quality scores are related to individual quality ratings of CSR reports with reference to several guidelines, e.g., the IFRS framework qualitative characteristics (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016), national and international corporate governance standards, e.g., OECD principles or Basel II (Abduh and AlAgeely, 2015), the KPMG international survey (Fernandez-Feijoo et al., 2014) or individual scores without any clear reliance on one standard or guideline (e.g., Janggu et al., 2014). To increase the reliability of their quality measures, only Htay et al. (2012) conducted an additional questionnaire to various experts. With regard to the increased resources, this strategy is an exception in former research studies.

The most relevant board composition variables are existence of a CSR committee (Amran et al., 2014), board independence (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Fernandez-Gago et al., 2016 with firm performance as a moderator variable; Abduh and AlAgeely, 2015; Amran et al., 2014; Janggu et al., 2014; Jizi et al., 2014; Frias-Aceituno et al., 2013; Htay et al., 2012; Prado-Lorenzo et al., 2009),financial, legal or other expertise of the board members (Dienes and Veite, 2016; Jizi et al., 2014), CEO duality model (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Abduh and AlAgeely, 2015; Giannaraakis et al., 2014; Jizi et al., 2014), former managers on the supervisory board as a substitute for the CEO duality model in the two-tier system (Dienes and Veite, 2016), gender diversity (Dienes and Veite, 2016; Amran et al., 2014; Fernandez-Feijoo et al., 2014; Giannaraakis et al., 2014; Frias-Aceituno et al., 2013; Fernandez- Feijoo et al., 2012), foreign diversity (Janggu et al., 2014; Frias-Aceituno et al., 2013), board activity (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Dienes and Veite, 2016; Jizi et al., 2014; Frias-Aceituno et al., 2013) and board size (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016; Dienes and Veite, 2016; Abduh and AlAgeely, 2015; Amran et al., 2014; Janggu et al., 2014; Jizi et al., 2014; Frias-Aceituno et al., 2013; Htay et al., 2012), audit committee and compensation committee size (Alotaibi and Hussainey, 2016).

Amran et al. (2014) is the only included study that found a positive link between the implementation of CSR committees and CSR reporting quality in a multinational sample from the Asia-Pacific region. Their quality measure was linked to a weighted score of several items, e.g., the adoption of CSR reporting guidelines. Board independence was found to have a positive link to CSR reporting quality in the Islamic financial institutions sector in a multinational sample (Abduh and AlAgeely, 2015). The same results were stated by Jizi et al. (2014) for a US sample of banks and by Htay et al. (2012) for Malaysian banks. Jizi et al. (2014) relied on the Haniffa and Cooke (2005) structure, but used a weighted quality score, whereas Htay et al. (2012) deducted an individual score. In contrast to these positive results restricted to the banking industry, Alotaibi and Hussainey (2016) state a negative link between independence and CSR reporting quality in Saudi Arabia outside the banking sector, measured by the compliance with IFRS framework characteristics. A negative relationship was also found by Prado-Lorenzo et al. (2009) for Spanish companies. In their study, the weighted CSR reporting quality score was measured by the existence of triple bottom line disclosures, GRI adoption and compliance with GRI by management. Fernandez-Gago et al. (2016) also came to the conclusion in a Spanish setting that board independence is related to better GSR reporting quality (based on the Observatio Score) and that firm performance (Return on Assets) moderates this relationship.

With regard to the CEO duality model, Jizi et al. (2014) found a positive impact on a weighted quality score GSR reporting as a modification of the Haniffa and Cooke (2005) structure by US banks. The analysis by Dienes and Veite (2016) is the only study with a clear focus on the German two-tier system and the supervisory board composition. Based on an external GSR reporting quality score (“IÖW (!!!Author decrypt)/future score”), the authors state that gender diversity in the supervisory board increases GSR reporting. Fernandez-Feijoo et al. (2012) analyzed 250 companies in 22 countries and deducted an individual quality score with selected criteria as publication of a standalone report or CSR strategy disclosures. Gender diversity in the board of directors was positively related to CSR reporting. In a multinational study by Frias-Aceituno et al. (2013), only gender diversity and not foreign diversity contributes to better CSR reporting quality. Finally, the results on board size as a board composition variable are mixed. According to Abduh and AlAgeely (2015), board size is negatively related to CSR reporting in the Islamic banking industry. In a Saudi Arabian setting outside the banking sector, Alotaibi and Hussainey (2016) also found a positive impact of board size on CSR reporting. The same result was stated by Janggu et al. (2014) for 100 Malaysian companies, by Jizi et al. (2014) for listed commercial US banks and by Frias-Aceituno et al. (2013) in a multinational setting.

3. LIMITATIONSAND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

Ever since the early studies on board composition by Halme and Huse (1997) and Haniffa and Cooke (2005), the topic of whether and how board composition variables affect CSR reporting has gained more and more momentum in empirical-quantitative corporate governance and CSR reporting research. In addition to heterogeneity of the results of the analysis of the board composition variables, also, the CSR reporting measures are not comparable. In this context, we would like to stress the main limitations of the included studies. First, multi-period observations, comparisons of an international sample of companies, and multivariate regression and sensitivity analyses were not available in every case so that a valid measurement of the influence factors was not always possible. Only 11 of the 47 included studies chose a multinational sample in order to control for country-specific effects (e.g., case law versus code law, culture, and strength of the enforcement regime). The results of single-period analyses are restricted, for example, owing to legally driven changes in reporting behaviors over time that are only visible through a multi-period observation. No study directly focuses on possible impacts of the financial crisis of 2008-2009 on CSR reporting. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses or endogenous tests were not included in many studies. In this context, we have to mention that also a reverse relationship between CSR reporting and board composition may be possible. The quantity and quality variables used in the studies were also limited to content analyses of the CSR reports with an individual scoring metric. The respective content criteria and the scoring models, thus, have a degree of subjectivity, which potentially reduces the validity of the results. A weighting of the content criteria through a previous survey of CSR representatives can only partially reduce this limitation owing to a subjective selection of the representative groups. The comparability of the studies is likewise restricted, because, in addition to general analyses of board models and systems, corporate governance is subject to country-specific arrangements. Lastly, the studies under consideration focused on the one-tier system (with one exception for the German two-tier system by Dienes and Veite, 2016). As the one-tier system is not comparable to board composition effects in the two-tier system (management board and supervisory board), the transformation of the results of the included studies to other regimes (e.g., European member states) is not possible.

After explaining the limitations, we would like to give useful recommendations for researchers, practitioners and regulators. Critical reflection of methodological limitations offers a starting point for future improvements in study designs. If a reasonable number of studies exists, we suggest performing quantitative meta-analyses of selected board composition variables in the future. Meta-analyses get more and more attractive in current accounting and corporate governance research. A meta-analysis that focuses on the link between board composition and CSR reporting is not useful yet in view of the huge heterogeneity of the board composition variables and the CSR reporting measures (quantity and quality). We propose future meta-analyses on the link between board independence or gender diversity on CSR reporting quantity if they represent a satisfying amount of studies with regard to the international discussion.

Although the current literature review relies on board composition as group level corporate governance (see Figure 1 in Appendix), we stress that there are further variables of corporate governance (institutional, firm, and individual levels) that have interdependencies with group-level variables. As a result, these effects should be measured by means of interaction and/or moderation terms in future statistical models. The board composition variables that were taken into account in previous studies have interdependencies as well and should be specified. With respect to gender diversity, it remains open to question whether the presence of women in boards has an impact on CSR reporting. Thus, it remains to be analyzed to what extent female presence has a positive influence on the quality of reporting. The critical mass theory (Konrad et al., 2008) indicates that a critical mass of women in boards is necessary to change board attitude towards CSR reporting. Surprisingly, up to now, management compensation and the structure thereof has not been analyzed along these lines.

In the line with these recommendations, future research should also include other board composition variables that might have an impact on CSR reporting. The first useful variable to include in future CSR reporting research is board tenure diversity (Rao and Tilt, 2016b). Handajani et al. (2014) found that boards with longer tenure tend to be related with lower CSR reporting quality, suggesting that long-term relationships with other board members and management decrease their monitoring activities, which can become detrimental to CSR. Rao and Tilt (2016b) state that also short-term relationships may contribute to a limited awareness of CSR reporting, because the specific board member has only little firm-specific knowledge. Insofar, the authors recommend to include board tenure diversity as the mix of both long and short tenured directors as a suitable board composition variable and assume a positive impact on CSR reporting (Rao and Tilt, 2016b). Another variable which is not well recognized in current research on CSR reporting is the existence of multiple directorships. According to Elsakit and Worthington (2014), the participation of the chairman of the board in discussions regarding CSR reporting in different companies is expected to have a positive impact on CSR reporting. This relationship is justified by an increased knowledge and awareness of CSR reporting (Rao and Tilt, 2016b). Finally, as board diversity represents one of the main board composition variables in current empirical research, board outcome is the result of collective discussion so that an overall diversity variable is useful to analyze the combined effect of diversity on CSR reporting (Rao and Tilt, 2016b). The so called “Blau index” (Blau, 1977) has reached a key relevance in empirical diversity research, but not in CSR reporting research (Rao and Tilt, 2016b). As decisions in diverse boards are more robust, the authors also assume a positive relationship between overall diversity and CSR reporting.

Another interesting variable to include in further research designs is age diversity. Handajani et al. (2014) stressed that board age in Indonesia is linked to CSR reporting quantity in line with the GRI guidelines. As many national corporate governance codes have a clear recommendation on the age limit of board members, there should be more research on that topic in future board composition designs.

Moving beyond the current focus on empirical quantitative studies, we suggest undertaking qualitative empirical studies on the impact of board composition on CSR reporting quality. Interviews, surveys, case studies, and experiments involving representatives of corporate boards of directors should be performed to determine the boards self-assessments regarding their respective CSR reporting processes and to identify opportunities for improvement. Up to now, there is rather low empirical evidence about the communication process within the different board members and its committees with regard to the development and modification of CSR reporting. Recent empirical qualitative research shows a low information exchange between the accounting and the marketing department within the company, the latter of which is often responsible for the CSR reporting (Schaltegger and Zvezdov, 2015). Future research should address the decision of the board of directors to merge financial accounting, as well as CSR reporting into an integrated reporting (Veite and Stawinoga, 2017).

Our literature reviews state that multinational studies are not very common. There is a need for further research, because a key aspect is the impact of different cultures in different countries on board composition and CSR reporting practice as a mediator, with special reference to the risk of litigation (Morros, 2016). It is extremely important how different environments may contribute to the management incentives to adopt CSR reporting and increase their quality awareness. Culture is also relevant in view of the different ranges of stakeholder pressure on CSR reporting practice. However, the four culture aspects referring to the famous model by Hofstede should be extended in future research. Our literature reviews indicate that most of the studies and their related significances contribute to developing countries and only differ between banking industry and other industries. We encourage future researchers to focus on European member states with regard to the huge regulations on board composition and CSR reporting since the financial crisis of 2008-2009. In this context, the impact of the one-tier and two-tier system, which represent the different EU member states, should be analyzed. In addition to this, it seems to be important to analyze the different branches of non-financial industries to a greater extent (e.g., pharmacy, automobiles) as the contents of CSR reporting might differ.

Furthermore, no empirical study has analyzed the impact of board composition variables on integrated reporting from a national or multinational perspective. Integrated reporting and CSR reporting and their interactions should be studied in future research designs. Empirical research on integrated reporting is most necessary but not easy to realize in view of these aspects. This is connected with a heterogeneous quality level of integrated reporting and integrated thinking from an international perspective.

In line with our research contributions, our literature review also has main regulatory implications. In contrast to the US capital market, the European legislator and also other regimes (e.g., South Africa) have finalized several reform initiatives on board composition and CSR reporting since the financial crisis of 2008-2009. The intention of the regulators is to increase the motives for a broader stakeholder management that should result in a decision-useful CSR reporting. It is an important challenge and remains unclear to date if these regulations will positively contribute to board effectiveness and CSR reporting so far.

The related implementation and transaction costs and the market implications of a “good” CSR reporting for PIEs are rather a “black box”. A sustainable and ethical management behavior won’t be generally generated by stricter regulations on board composition and CSR reporting. The great discussion of green washing of CSR reporting and boilerplate information indicates that the board of directors must implement a sustainable vision and philosophy as a top down approach in accordance with the total employees and a consistent stakeholder dialogue. But in the end, every management of PIEs will focus on the financial performance so that the great challenge lies in the connection between financial and non-financial indicators (integrated thinking) as proposed in the voluntary integrated reporting model.

Finally, we would like to point out some practical implications. In general, the included studies in our literature review found rather low quality scores from an international perspective in their descriptive statistics. Insofar, there are many possibilities for improvements for CSR reporting activities from a practical view. Management should not only be aware of the CSR reporting costs, but also of the positive link to firm reputation and stakeholder trust, which could lead to better CSR and financial performance in the long

run. However, involvement in CSR practices may not generally be transformed into CSR reporting (Majeed et al., 2015). Insofar, firms without CSR reporting can be active in CSR management and may plan to introduce a CSR report in future. Even though some studies indicate that PIEs have higher CSR disclosure scores, also, small and medium sized entities are aware of CSR, especially family firms. Also, our results are not restricted to a special branch of industry. But it is important to have a clear research strand on financial institutions (e.g., Kilic et al., 2014) and stress that the traditional banking systems with its focus on financial reporting and financial key performance indicators must be extended by non financial value drivers.

CONCLUSION

As a supplement to financial accounting, CSR reporting according to the triple bottom line provides economic, environmental, as well as social information on corporations to various stakeholders on a voluntary basis. As CSR reporting is closely linked to internal corporate governance and management control, the present literature review analyzes the impact of the main board composition variables on CSR reporting quantity and quality: board committees (esp., audit and CSR committees), board independence, board expertise, CEO duality, board diversity (esp., gender and foreign), board activity, and board size.

We provided a stakeholder (agency) theoretical framework in which the central significance of board composition on CSR reporting, as well as the research framework employed in the respective studies are highlighted. We, then, provided a detailed literature analysis of the results of existing empirical research on the impact of board composition on CSR reporting. Following this, we outlined the data generation and research methods used in these studies (1) along with a separate evaluation of CSR reporting quantity (2) and CSR reporting quality (3). The results of the 47 studies indicate that the majority of the included studies rely on CSR reporting quantity and focus on developing countries. With regard to the analysis of branches of industries, there is a remarkable concentration on the banking industry in some research designs. We, then, explained current research limitations and offered recommendations to researchers, practice and regulators about future aspects in board composition and CSR reporting. While CEO duality, board activity and board size are commonly used as board composition variables, their explanatory power is limited in view of the diverse theoretical impact on CSR reporting. We found that board independence and gender diversity are also often used as proxies for board effectiveness, but other related factors, e.g., board expertise or foreign diversity are very rare. We encourage future researchers to include more board composition variables, e.g., multiple directorships, board tenure, in line with the empirical corporate governance research in other topics. To increase the validity of research in this area, additional qualitative research designs, e.g., surveys, interviews or case studies of the board, will be useful. We also criticize the diverse CSR reporting measures in view of their lack of comparability and the restricted objectivity, especially by measuring CSR reporting quality and propose a detailed stakeholder dialogue before establishing a weighted disclosure score.

Remarkably, the existing research primarily focuses on board systems in developing countries in the Asian region. Furthermore, the banking industry is focused in some research designs. In view of the huge regulatory measures within the EU in the context of board composition and CSR reporting (e.g., EU CSR Directive), future research should analyze their relationship in a multinational sample of EU member states with one-tier and two-tier systems with a separation of different branches of industries. Furthermore, on the basis of an international comparison, the US and European corporate governance system (insider versus outsider model) should be analyzed to a greater amount.

Finally, the growing importance of integrated reporting for PIEs questions the further development of CSR reporting. Some companies have even started to replace their “traditional” CSR report and imple-

ment an integrated report. The interpretation of integrated reporting by the IIRC is an additional reporting instrument that complements the CSR report as a compromized report that includes the material information of the financial and CSR report. Insofar, integrated reporting can have a huge impact on CSR reporting as well. This could positively affect the scope and quality of empirical content analyses of all forms of reporting in the future, as the quantification of non-financial items are crucial for stakeholder management. In this context, we are aware of the fact that UK was one of the drivers of integrated reporting within the EU and future studies on the impact of the “Brexit” resolution should be kept in mind. The applicability of recent research results on CSR reporting to integrated reporting had to be neglected owing to the divergent frameworks of CSR reporting and integrated reporting. Nevertheless, it must be assumed that recent research designs tailored to studying board composition and CSR reporting will be used for integrated reporting in the coming years.

REFERENCES

- Abduh, M., and AlAgeely, A. M. (2015). The Impact of corporate governance on CSR disclosure in Islamic banks: empirical evidence from GCC countries. Middle East Journal of Management, 2, 283-295.

- Ali, M .A. M., and Atan, R. (2013). The Relationship between Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure. A case of High Malaysian Sustainability Companies and Global Sustainability Companies. South East Asia Journal of Contemporary Business, Economics and Law, 3, 39-48.

- Alotaibi, K. O., and Hussainey, K. (2016). Determinants of CSR disclosure quantity and quality: Evidence from non- financial listed firms in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance (online first).

- Amran, A., Lee, S. R, and Devi, S. (2014). The Influence of Governance Structure and Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility Toward Sustainability Reporting Quality. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23, 217-235.

- Barako, D. G., and Brown, A. M. (2008). Corporate Social Reporting and board representation: evidence from the Kenyan banking sector. Journal of Management and Governance, 12, 309-324.

- Benomran, N., Haat, M. H. C., Hashim, H. B., and Mohamad, N. R. B. (2015). Influence of Corporate Governance on the Extent of Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Reporting. Journal of Environment and Ecology, 6, 48-68.

- Blau, R M. (1977). Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure. Free Press, New York.

- Bukair, A. A., and Rahman, A. A. The Effect of the Board of Directors’ Characteristics on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure by Islamic Banks. Journal of Management Research, 7, 506-519.

- Byron, K., and Post, C. Women on Boards of Directors and Corporate Social Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24, 428-442.

- Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate Social Responsibility. Business and Society, 38, 268-295.

- Darus, E, Sawani, Y„ Zain, M. M., and Janggu, T. (2014). Impediments to CSR assurance in an emerging economy. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29, 253-267.

- Darus, E, Isa, N. H. M, Yusoff, H., and Arshad, R. (2015). Corporate Governance and Business Capabilities: Strategic Factors for Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Journal of Accounting and Auditing: Research & Practice, 1-9.

- Das, S., Dixon, R., and Michael, A. (2015). Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: A Longitudinal Study of Listed Banking Companies in Bangladesh. World Review of Business Research, 5, 130-154.

- Dienes, D., and Veite, P. (2016). The Impact of Supervisory Board Composition on CSR Reporting. Evidence from the German Two-Tier System. Sustainability, 8(63), 1-20.

- Dienes, D., Sassen, R., and Fischer, F. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 7, 154-189.

- Dilling, P. (2010). Sustainability Reporting in a global context: what are the characteristics of corporations that provide high quality sustainability reports. International Business 8c Economics Research Journal, 9, 19-30.

- Eccles, R. G., and Krzus, M. P. (2015). The Integrated Reporting Movement - Meaning, Momentum Motives, and Materiality. Wiley: Hoboken.

- Elsakit, О. M., and Worthington, A. C. (2014). The Impact of Corporate Characteristics and Corporate Governance on Corporate Social and Environmental Disclosure: A Literature Review. International Journal of Business and Management, 9, 1-15.

- Faisal, E, Tower, G., and Rusmin, R. (2012). Legitimising corporate sustainability reporting throughout the world. Australian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 6, 19-34.

- Federation of European Accountants. (2002). FEE Discussion Paper Providing Assurance on Sustainability Reports. Retrieved from http://www.fee.be/images/publica- tions/sustainability/DP_Provid- ing_Assurance_on_Sustainabil-ity_Reportsl632005451020.pdf

- Federation of European Accountants. (2015). EU Directive on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information - The role of practitioners in providing assurance - position paper. Retrieved from http://www.accountancyeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/1512_EU_Directive_on_NFI.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2017).

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B., Romero, S., and Ruiz, S. (2012). Does Board Gender Composition affect Corporate Scoial Responsibility Reporting? International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3, 31-38.

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B., Romero, S., and Ruiz-Blanco, S. (2014). Women on Boards. Do they affect Sustainability Reporting? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 21, 351-364.

- Fernandez-Gago, R., Cabeza- Garcia, L., and Nieto, M. (2016). Corporate social responsibility, board of directors, and firm performance: an analysis of their relationships. Review of Management Science, 10, 85-104.

- Fifka, M. (2012). The development and state of research on social and environmental reporting in global comparison. Journal für Betriebswirtschaft, 62, 45-84.

- Frias-Aceituno, J. V., Rodriguez- Ariza, L., and Garcia-Sanchez,

- M. (2013a). The Role of the Board in the Dissemination of Integrated Corporate Social Reporting. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 20, 219-233.

- Giannarakis, G., Konteos, G., and Sariannidis, N. (2014). Financial, governance and environmental determinants of corporate social responsible disclosure. Management Decision, 52, 1928- 1951.

- GRI. (2013). G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. Reporting Principles and Standard Disclosures, Amsterdam. Retrieved from https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/GRIG4-Part1-Reporting-Principles-and-Standard-Disclosures.pdf

- Guan, J., and Noronha, C. (2011). Corporate social responsibility reporting research in the Chinese academia: a critical review. Social Responsibility Journal, 9, 33-55.

- Habbash, M. (2016). Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Journal of Economic and Social Development, 3, 87-103.

- Hahn, R., and Kühnen, M. (2013). Determinants of sustainability reporting: a review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 59, 5-21.

- Halme, M., and Huse, M. (1997). The Influence of Corporate Governance, Industry and Country Factors on Environmental Reporting. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13, 137-157.

- Handajani, D. C., Subroto, B., Sutrisno, T, and Sarawati, E. (2014). Does board diversity matter on corporate social disclosure? Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5, 8-16.

- Haniffa, R. M., and Cooke, T. E. (2005). The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24, 391-430.

- Herda, D. N., Taylor, M. E., and Winterbotham, G. (2013). The Effect of Board Independence on the Sustainability Reporting Practices of Large U.S. Firms. Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting 6, 25-44.

- Htay, S. N. N„ Rashid, H. M. A., Adnan, M. A., and Meera, A.K.M. (2012). Impact of Corporate Governance on Social and Environmental Information Disclosure of Malaysian Listed Banks: Panel Data Analysis. Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting 4, 1-24.

- Jain, T, and Jamali, D. (2016). Looking Inside the Black Box: The Effect of Corporate Governance on Corporate Social Responsibility. Corporate governance: an international review, 24, 253-273.

- Janggu, T, Darus, E, Zain, M. M., and Sawani, Y. (2014). Does Good Corporate Governance Lead to Better Sustainability Reporting? An Analysis Using Structural Equation Modeling. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 145, 138-145.

- Jizi, M. I., Salama, A., Dixon, R., and Sträfling, R. (2014). Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Resonsibility Disclosure: Evidence from the US Banking Sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 601-615.

- Johansen, T. R. (2016). EU Regulation of Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 36, 1-9.

- Kent, P., and Monem, R. (2008). What Drives TBL Reporting: Good governance or threat to legitimacy? Australian Accounting Review, 47, 297-309.

- Khan, A., Muttakin, M. B., and Siddiqui, J. (2013). Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures: Evidence from Emerging Economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 114, 207-223.

- Khan, H. U. Z. (2010). The effect of corporate governance elements on corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting. International Journal of Law and Management, 52, 82-109.

- Kilic, M., Kuzey, C., and Uyar, A. (2015). The impact of ownership and board structure on Corporate

Social Responsibility (LSR) reporting in the Turkish banking industry. Corporate Governance, 15, 357-374. - Kolk, A., and van Tulder, R. (2010). International Business, Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development. International Business Review, 19, 119-125.

- Konrad, A. M., Kramer, V, and Erkut, S. (2008). Critical mass: the impact of three or more women on corporate boards. Organizational Dynamics, 37, 145-164.

- Li, S., Fetscherin, M., Alon, I., Lattemann, C., and Yeh, K. (2010). Corporate Social Responsibility in Emerging Markets. The Importance of the Governance Environment. Management International Review, 50, 635-654.

- Light, R., and Smith, P. (1971). Accumulating Evidence: Procedures for Resolving Contradictions among Different Research Studies. Harvard Educational Review, 41, 429-471.

- Lim, Y. Z., Talha, M., Mohammed, J., and Sallehhuddin, A. (2008). Corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance in Malaysia. International Journal of Behavioral Accounting and Finance, 1, 67-89.

- Mahoney, L. S., Thorne, L., Cecil, L., and LaGore, W. (2013). A research note on standalone corporate social responsibility reports: Signaling or greenwashing? Critical perspectives on Accounting 24, 350-359.

- Majeed, S., Aziz, T, and Saleem, S. (2015). The Effect of Corporate Governance Elements on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure: An Empirical Evidence from Listed Companies at KSE Pakistan. International Journal of Financial Studies, 3, 530-556.

- Malik, M. (2015). Value- Enhancing Capabilities of CSR: A Brief Review of Contemporary Literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 127, 419-438.

- McConnell, J. J., and Servaes, H. (1990). Additional evidence on equity ownership and corporate value. Journal of Financial Economics, 27, 595-612.

- Michelon, G. (2011). Sustainability Disclosure and Reputation: A Comparative Study. Corporate Reputation Review, 14, 79-96.

- Michelon, G., and Parbonetti, A. (2012). The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. Journal of Management and Governance, 16, 477-509.

- Mio, C. (2016). Integrated Reporting: The IIRC Framework. In Mio, C. (Ed.), Integrated Reporting - A New Accounting Disclosure (pp. 1-18). Palgrave Macmillan: London.

- Monciardini, D. (2016). The ‘Coalition of the Unlikely’ Driving the EU Regulatory Process of Non-Financial Reporting. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 36, 76-89.

- Moneva, J. M., Archel, P., and Correa, C. (2006). GRI and the camouflaging of corporate unstainability. Accounting Forum, 30, 121-137.

- Murphy, D., and McGrath, D. (2013). ESG reporting - class actions, deterrence, and avoidance. Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal, 4, 216-235.

- Muttakin, M. B., and Subraamaniam, N. (2015). Firm ownership and board characteristics. Do they matter for corporate social responsibility disclosure of Indian companies? Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal, 6, 138-165.

- Muttakin, M. B., Khan, A., and Mihret, D. G. (2016). The Effect of Board Capital and CEO Power on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures. Journal of Business Ethics (online first).

- Paetzmann, K. (2016). Sustainable Corporate Governance. Zum Sustainability Reporting de lege ferenda. Zeitschrift für Corporate Governance, 6, 279-283.

- Post, C., and Byron, K. (2015). Women on boards and firm financial performance. A metaanalysis. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 1546-1571.

- Prado-Lorenzo, J.-M., Gallego- Alvarez, I., and Garcia-Sanchez, I. M. (2009). Stakeholder Engagement and Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: the Ownership Structure Effect. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16, 94-107.

- Prado-Lorenzo, J. M., Garcia- Sanchez, I. M., and Gallego- Alvarez, I. (2012). Effects of Activist Shareholding on Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting Practices. An Empirical Study in Spain. Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, 17, 7-16.

- Ramus, C. A., and Montiel, I. (2005). When Are Corporate Environmental Policies a Form of Greenwashing? Business Society, 44, 377-414.

- Rao, K., and Tilt, C. (2016a). Board composition and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Diversity, Gender, Strategy and Decision Making. Journal of Business Ethics (online first).

- Rao, K., and Tilt, C. (2016b). Board diversity and CSR reporting: an Australian study. Meditari Accountancy Research, 24, 182-210.

- Rouf, M. A. (2011). The Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: A study of Listed companies in Bangladesh. Business and Economics Research Journal, 2, 19-32.

- Rowbottom, N., and Locke, N. (2016). The Emergence of <IR>. Accounting and Business Research, 46, 83-115.

- Said, R., Zainuddin, Y. FL, and Naron, N. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Social Responsiblity Journal, 5, 212-226.

- Schaltegger, S., and Zvezdov, D. (2015). Gatekeepers of sustainability information: exploring the roles of accountants. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 11, 333- 361.

- Sethi, S. P., Martell, T. F., and Demir, M. (2015). Enhancing the Role and Effectiveness of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports: The Missing Element of Content Verification and Integrity Assurance. Journal of Business Ethics (online first).

- Seuring, S., and Mueller, M. (2008). Core issues in sustainable supply chain management - A Delphi study. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17, 455-466.

- Shamil, M. M„ Shaikh, J. M„ Ho, Р.-L., and Krishnan, A. (2014). The influence of board characteristics on sustainability reporting. Empirical evidence from Sri Lankan firms. Asian Review of Accounting 22, 78-97.

- Sharif, M., and Rashid, K. (2014). Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting: an empirical evidence from commercial banks (CB) in Pakistan. Quality & Quantity, 48, 2501-2521.

- Simnett, R., and Huggins, A. L. (2015). Integrated reporting and assurance: where can research add value? Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal, 6, 29-53.

- Siregar, S. V, and Bachtiar, Y. (2010). Corporate social reporting: empirical evidence from Indonesia Stock Exchange. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 3, 241-252.

- Sundarasen, S. D. D., Je-Yen, T., and Rajangam, N. (2016). Board composition and corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Corporate Governance, 16, 35-53.

- Veite, P., and Stawinoga, M. Integrated reporting: The current state of empirical research, limitations and future research implications. Journal of Management Control (online first).

- Wood, W., Polek, D., and Aiken, C. (1985). Sex differences in group task performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 63-71.

- Zorio, A., Garcia-Benau, M. A., Sierra, L. (2013). Sustainability development and the quality of assurance reports. Empirical evidence. Business Strategy and the Environment, 22, 484-500.

APPENDIX