Climate of Concern - A Search for Effective Strategies for Teaching Children about Global Warming

Published: April 10, 2009

Latest article update: Dec. 30, 2022

Abstract

Recent research suggests that the issue of global warming is one of great concern for Australian children. This point to the need for effective teaching about this issue. Children should be properly informed about actions that help reduce carbon emissions as this may give them a sense of empowerment and go some way to alleviating concerns. This study followed the development in the knowledge of global warming of 29 primary school students in year 6 (the final year of primary) from two regional Australian schools over one school term. A hands-on science unit dealing specifically with global warming was prepared and taught over a period of eight weeks. A mixed methods approach was adopted and data was gathered through pre- and post-testing, through post intervention interviews. The findings of the study indicated that after the unit, students had a clearer understanding of the science of climate change, with the largest improvement in student knowledge occurring where the students had engaged in hands on activities or had effective visual aids. The data also indicated that an increase in knowledge was accompanied by an increase in levels concern in some cases. However, there was also an overall increase in students’ belief about their ability to make a positive impact in relation to global warming and climate change.

Keywords

Climate change, effect size, Global Warming, environmental knowledge, teaching intervention, primary school students

Introduction and Literature Review

In 2006 the children’s current affairs television show ‘Behind the News’ surveyed school aged children from across Australia, to identify issues that worry children. In equal first place, along with the death of a friend or family member, the survey participants listed the environment (MacMullin, 2007). It is possible that this could be attributed at least in part, to the heightened public awareness and media coverage of issues such as global warming, climate change and drought. Whatever its cause, the environment and the threats posed to it appear to be on children’s minds. According to Kefford (2006) there is danger that too much exposure to such daunting issues as global warming may lead to feelings of helplessness and therefore be a demotivation to act for change. However, there is also the risk that constant contact with this important issue may produce children who are desensitized to it (Nicholson-Cole, 2005).

Ideally, children should be informed about the areas of personal, national and historic concern and yet feel empowered to make positive contributions. Schools should be able to play a vital role by teaching about the environment and environmental issues but also in encouraging children to be advocates for their environment and actively participate in positive action towards the environment. However, according the literature (e.g. Jensen & Schnack, 1997), a clear understanding of environmental issues is a pre-requisite for taking positive action.

To date there has been limited research on primary age students’ knowledge and understanding of global warming and how this might be improved. This study was undertaken to explore the prior knowledge and understanding that final year primary students had about the issue of global warming and whether a teaching intervention specifically addressing that issue could improve this.

Previous studies of environmental knowledge and attitudes undertaken with students in Australia have largely been conducted at the secondary level. In a two-year study of secondary students in Melbourne and Brisbane carried out by Connell et al (1999), participants identified issues such as air and water pollution and urbanisation as their main areas of concern with little specific reference to global warming. This may have been because at that time global warming lacked the type of media profile it has recently attracted. However, a study conducted by Fisher (1998) which explicitly questioned students about the issue of the Greenhouse Effect, found reasonably high levels of knowledge in the 11 to 17 year olds he interviewed. This study, which compared the understandings of Australian children with their peers in the United Kingdom, found that most students were able to identify carbon dioxide as a gas that contributed to the Greenhouse Effect but not the other gases such as methane. Australian students were also able to make the connection between the felling of trees and the Greenhouse Effect. Despite this, Fisher found large gaps in the understandings held by the participants, especially when asked to explain the phenomenon in scientific terms.

A more recent study on knowledge about global warming undertaken in Australia by Skamp, Boyes and Stanisstreet (2007) did include upper primary students. This study examined students’ knowledge and understanding of global warming and the Greenhouse effect, but also attempted to determine students’ willingness to act in ways that might reduce this. Many of the younger students, in particular 11 and 12 year olds, identified improving the water quality of the ocean, reducing street litter and the use of pesticides as steps to be taken to help reduce global warming. The apparent confusion between general environmental issues and global warming suggests that children hold many misconceptions about global warming and climate change.

The research project reported in this paper was designed to provide more in sight into these misconceptions and to trial and evaluate a teaching intervention to address these. The specific research questions for this project where:

- What alternatives or misconceptions do primary students have about global warm ing prior to intervention?

- Can a teaching intervention based upon a constructivist view of learning and critical theory improve primary students’ understanding of global warming?

- Will such an approach provide insight into students’ attitudes in regards to global warming?

Theoretical Considerations

The theoretical context of this research is underpinned by social constructivism that claims that the learning process is built through interaction with a variety of information sources (McInerney & McInerney, 2002). A child’s knowledge of global warming may be built over time with input from family, the media, teachers, school curriculum, and personal experiences and so on. This research set out to understand the meanings children had constructed on the issue global warming, to identify possible misconceptions and to attempt to improve their knowledge base and correct these misconceptions. However, the study was not limited to simply documenting knowledge levels but also to attempting to identify connections between this knowledge and the attitudes held by the subjects.

Context of the Study and Participants

This research was conducted in a regional centre in rural New South Wales, Australia, where great importance is placed upon primary production within the local economy. Most of the climatic issues faced by rural communities are common to urban areas, such as decreasing rainfall and increasing average temperatures. However, recent severe droughts have meant much reduced agricultural productivity and have had a negative effect on the micro-economy of rural areas. This has resulted in significant financial hardship for farmers and those in related industries (Department of the Environment and Heritage, 2005).

In total 29, class 6 (final year) primary students from a two regional primary schools took part in this study. Of these 22 were male and seven female. This was not a true reflection of the make up but was determined by the parental consent received. A total 11 of these participants (8 males and 3 females) were purposefully chosen for the second phase of the research, involving semi-structured interviews. Final year primary students were deliberately selected for this research as the content of the teaching unit that formed the intervention in this study was cognitively sophisticated. Consequently final year students were considered best placed to understand it.

Methodology

This study employed both qualitative and quantitative methods within a mixed methods research design comprising two phases. Phase 1 involved a pre-test, a teaching intervention and a post-test. To this end a 25 item, true/false knowledge based survey instrument was developed and administration to 29 final year primary school students. The survey was developed by the first author and drew to some extent on previous surveys produced by Summers et al (2001) and Boyes and Stanisstreet (1993). A pilot study was conducted to validate the content of the survey and item analysis was carried out to remove items that did not discriminate effectively. The survey instrument, which also contained two attitudinal items, (see Appendix A) acted as both the pre and post-test for the intervention.

The second phase of the study involved interviewing a number of the participants from phase 1 using semi structured interviews. The sample of students involved in this phase consisted of 8 boys and 3 girls. These students were selected for a number of reasons. Some were selected because they had shown substantial improvement in their survey scores after the teaching intervention. Others were selected because they showed little or no improvement and some were randomly selected.

The interview protocol probed students’ knowledge and understanding of issues related to global wanning in order to get greater insight into the survey findings. This also allowed for the triangulation of data from phase 1. Some additional questions about the teaching intervention, environmental attitudes and behaviour were also asked during this phase.

Data analysis

The data from the pre and post administration of the survey were entered into a spreadsheet and graphs were produced showing the frequency of correct responses pre and post intervention. SPSS was used to test for statistical significance between pre and post responses and EXCEL to test for effect size. The two ‘attitude’ questions at the end of the survey were compared in a similar fashion.

Phase 2 interviews were electronically recorded, using a digital recorder, and fully transcribed. Each transcript was then analyzed for the knowledge and understanding of global warming exhibited by the participant, their views about the teaching intervention and well as their attitudes to this particular issue.

The Intervention

Rather than utilise an existing environmental education program, it was decided that a unit would be written specifically for the purpose of this research project. The unit was written to provide students with global warming related learning experiences that would allow them to address issues that arose from the findings of the first administration of the survey. As this unit was taught to students in NSW, the NSW syllabi outcomes from the Key Learning Areas of Human Society and Its Environment and Science and Technology formed general guidelines for the intended outcomes of this unit. Those outcomes included:

- Demonstrates an understanding of the interconnectedness between Australia and global environments and how individuals and groups can act in an ecologically responsible manner.

- Explains how various beliefs and practices influence the ways in which people interact with, change and value their environment.

- Identifies, describes and evaluates the interactions between living things and their effects on the environment.

The scope and sequence of the unit is outlined in Appendix В and an example of a lesson plan is presented in Appendix C. Because energy is a conceptually difficult topic, some revision was undertaken before the unit began in which the issue of energy was addressed from a number of perspectives. This involved amongst other things, identifying energy sources (both renewable and non-renewable), and discussing the energy consumption of various appliances by examining their wattage ratings.

The teaching strategies employed in this unit aligned closely with the NSW Department of Education and Training Quality Teaching Model. This model was designed to enhance the overall quality of the pedagogy in NSW schools and to assist teachers to be reflective practitioners. It consists of three dimensions which aim to foster “high levels of intellectual quality... [promote] a quality learning environment...and make explicit to students the significance of their work” (NSWDET, 2003).

Findings and Discussion

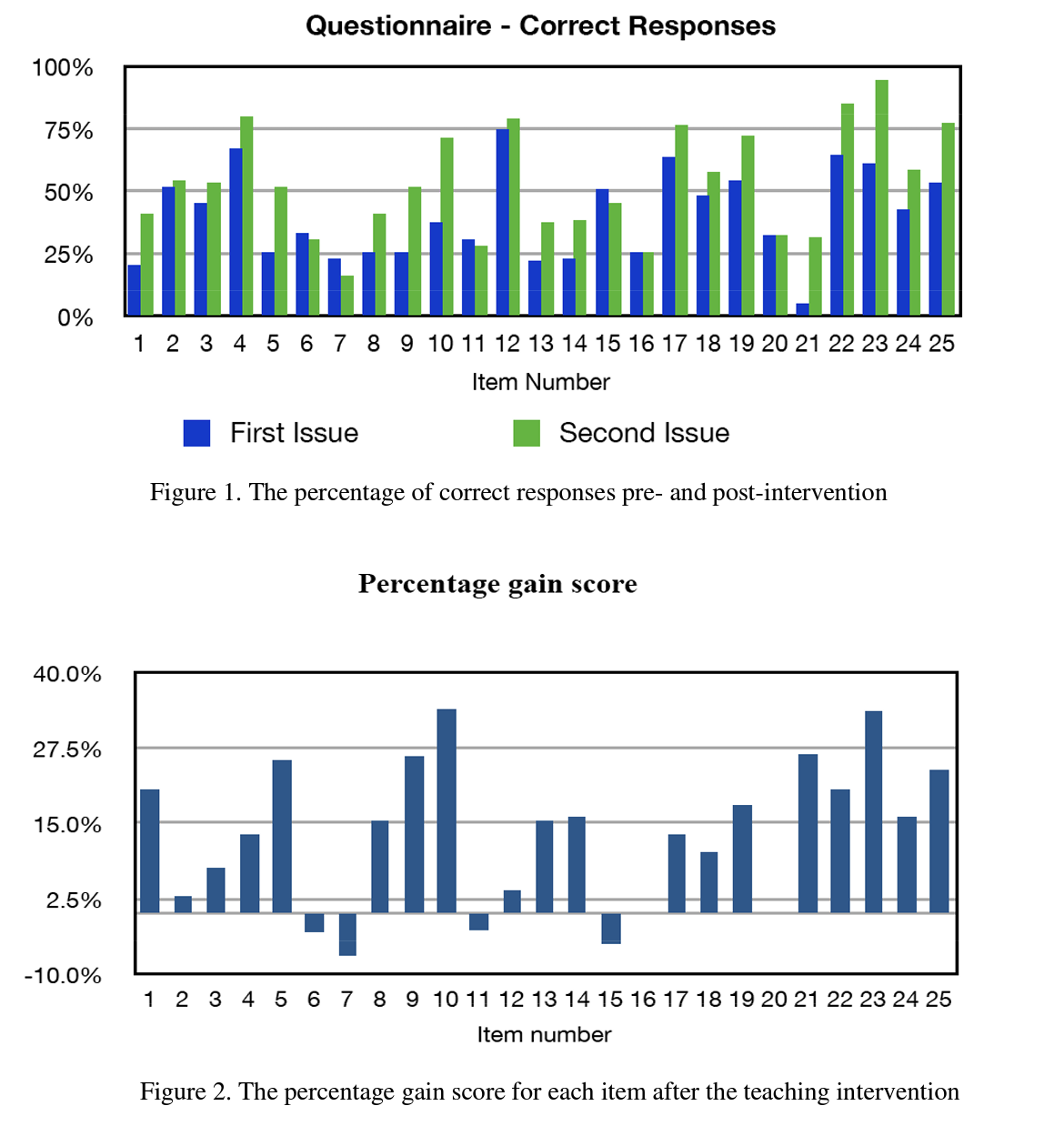

The survey designed for this unit was issued twice, once prior to the teaching intervention and once immediately after. The pre and post results for the 29 students on each item are presented in Figures 1 and 2 below. Figure 1 shows the percentage of correct responses pre- and postintervention and Figure 2 presents the percentage gain score for each item.

Of the 25 items, an increase in correct responses can be seen in 19, a small decrease in four and no change in two. Overall, 5 items showed a statistically significant increase in the correct response on the post-test (p<0.5). Effect size was also calculated, as given the relatively small sample, it offered a more meaningful measure of change. According to Coe (2002), effect size is particularly valuable for quantifying the effectiveness of a specific intervention. When assessing effect size, 0.3 indicates normal development that would have occurred even without the intervention. Ten items in this data had an effect size of 0.4 or greater, indicating improvement. The Effect Size for all of the items is presented in Table 1.

Some of the increases in correct responses were quite large, increasing by a factor of 20% or more. For example, item 10 asked students to identify as true or false the statement, “If we didn’t have the Greenhouse Effect, there wouldn’t be any people or animals on Earth.” In the first administration of the survey 37.5% of students correctly answered “True”. Post teaching intervention 71.5% of students were able to identify that this was indeed true, an increase of 34%, with an effect size of 0.71 indicating a very large improvement. Thus it appeared the unit had been largely successful in helping students distinguish between the natural Greenhouse Effect and the enhanced Greenhouse Effect. Furthermore, item 23 (“Buying locally produced food is better for our environment than buying food produced overseas”) provided a similar increase from 61.5% correct in issue one to 95% correct in issue two (with an effect size of 0.71).

The topic of transportation of food and the energy implications of this when viewed from an environmental perspective was a particular focus of the intervention, and this appeared to have been successful in increasing awareness of this issue. Such an improvement is important as it can impact on environmental behaviour. Once students are aware of the environmental issues relating to the transportation of products they are better placed to make informed choices in favour of the environment (Boyes & Stanisstreet, 1993).

Item 21 (As the ice in places like the Arctic melts, sea levels will rise) displayed an effect size of 0.78. The improvement post intervention may reflect an aspect of learning that appears to have been particularly effective for the participants. Several experiments relating to sea level rise were conducted and discussed in depth and these hands on activities appear to have been effective in improving the students’ understanding of this issue. One of these activities involved placing a large cube of ice in a container of water. The initial water level was marked and the ice allowed to melt, then the final water level recorded. This replicated the Arctic ice in the oceans.

Item 5 also showed a substantial effect size of 0.65. This item (There is a link between air conditioners and global warming) formed the basis for several class discussions about home

Table 1 The Effect Size for all of the Items in the Survey - Post-Intervention energy consumption and the increasing access to and affordability of domestic air conditioning products.

Item Number | Effect Size | Item Number | Effect Size |

1 | 0.44 | 14 | 0.43 |

2 | 0.14 | 15 | -0.07 |

3 | 0.13 | 16 | 0 |

4 | 0.32 | 17 | 0.22 |

5 | 0.65 | 18 | 0.2 |

6 | -0.07 | 19 | 0.43 |

7 | -0.17 | 20 | 0 |

8 | 0.44 | 21 | 0.78 |

9 | 0.22 | 22 | 0.41 |

10 | 0.71 | 23 | 0.91 |

11 | -0.07 | 24 | 0.34 |

12 | 0.08 | 25 | 0.68 |

13 | 0.37 |

|

|

There were, however, also some items that showed a decrease in the correct responses after the intervention. For example, item 6 which indicted a 3% drop, item 7 dropped by 7% and item 11 by 2.5% but these changes are not considered to be statistically significant. However, item 15 was notable, as it showed a reduction of 10% in correct answers post instruction, with an effect size of -0.71. This topic (The Greenhouse Effect can be seen from space) was not the focus of any specific activity and as such received only a small mention in class discussions. It is possible that students simply guessed at this item during both the first and second survey with more guessing incorrectly in the second. However, it is also possible that the teaching itself inadvertently reinforced or increased this misconception. There is certainly evidence from the science education literature that misconceptions can be introduced or reinforced through teaching, albeit inadvertently (see Osborne and Cosgrove, 1983).

Two items (16 and 20) produced the same results in the pre and post survey, and therefore showed no gain. Both items based upon some commonly held misconceptions. Item 16 (Removing lead from petrol reduces the effects of global warming) and item 20 (Skin cancer can be caused by global warming) continued to cause some confusion, even after the intervention. These ‘misconception items’ showed similar results to those found by Boyes and Stanisstreet (1993) and Summers et al (2001) indicating that they are highly resistant to change. However, overall, it appeared that the teaching intervention did improve the understanding of global warming held by the students in this study.

Interview findings

The interview data provided further insight into a number of misconceptions that students held about the global warming and the Greenhouse Effect. The survey indicated a tendency by some children to group several separate environmental issues as one, under the issue of global warming. For example, when questioned about the role that clean rivers play in global warming, only 31% of students in the pre test were able to correctly identify that these were two separate issues. This item was one of the three to register a decrease in correct responses in the post-test. When specifically questioned about the impact that cleaning up rivers might have upon reducing global warming, some children were able to correctly explain that these issues were not linked, whilst others continued to hold misconceptions. The following responses show these two views (the names of students have been changed):

Interviewer: If we had a way of making sure these was no rubbish in any rivers, is that going to help reduce global warming

Amy: I don’t think so. It’s just about keeping our environment clean so we have animals.

This contrasted with:

Interviewer: Thinking about rivers now. If we could have a way of keeping the rubbish out of rivers so they had no rubbish floating in them, is that going to help reduce global warming?

Douglas: Yes

Interviewer: How would that work?

Douglas: It will keep the animals in the river alive from choking on [the rubbish] and the rivers, most rivers lead into the oceans ... and if there was no animals in the seas then things get out of control.

Douglas appeared to have an understanding of the impact of pollution on biodiversity in the rivers and oceans, but he incorrectly attempted to find a link between this issue and global warming. Similarly, when the children were asked to explain what causes the hole in the ozone layer, some children could provide accurate information:

Interviewer: Can you tell me what causes the hole in the ozone layer?

Hannah: CFC’s.

Interviewer: Do you know where we find those?

Hannah: Cans - aerosol cans.

Other students were partly correct:

Jason: Like, petrol fumes coming out of cars and chemicals and all sorts of things. Like hairsprays and things like that.

Douglas: The CFC’s and they make a hole and sunlight comes in which warms everything up.

Douglas’ s comment about the cause of the hole in the ozone layer was correct but he then confused the ozone issue with that of the Greenhouse Effect. When questioned about the ozone layer in the survey, (“Holes in the Earth’s ozone layer are caused by global warming”), two-thirds of the children were stating that this was ‘True’, even after the intervention. As previously discussed, this confusion between the global warming and the hole in the ozone layer, is one of the most commonly held misconceptions by many individuals, not only children. Furthermore, it appeared that teaching primary children the difference between these concepts had little impact, possibly because, the notion of a hole in the ozone layer letting in the heat that increases global warming is intuitively very appealing to young children.

Another area that caused some confusion was the topic of domestic energy consumption. In the survey students were asked to identify as correct or incorrect the statement that “The most electricity used in the house is used by the lights.” It should be noted here that it is possible for this to actually be true, but it would be extremely unusual, as in Australia, generally the largest domestic consumption of electricity in most houses due to heating and cooling appliances particularly air conditioners although large televisions and refrigerators also contribute. In the pre-test, 33% of students responded correctly, a figure that remained post-test. The interviews revealed further insight into why there was confusion about this issue.

Ben: I reckon it would be the TV ‘cause some people don’t turn it off or

unplug it - they just leave it on. It’s still in and using electricity.

Amy: It’s mostly used by the fridge ‘cause it’s on all the time and the lights

are only on at night.

Interviewer: If I said to you ‘the most electricity used in a house is from the lights,’ do you think I’d be wrong or right?

Jason: I think you’d be right.

The fact that lights are so obvious to children in their homes while high-energy consumers such as hot water systems are much less so, might explain the tendency of some children to identify lighting as a major consumer.

Additionally, the survey included statements such as “Using nuclear power causes global warming”, “Chemicals used for cleaning are major contributors to global warming” and “Pollution from cars is the biggest contributor to global warming.” Even after specific teaching related to these and other misconceptions, although there was an improvement, it was relatively small. This suggested that like many misconceptions held by children these were highly resistant to change even in the face of persuasive teaching (Boyes & Stanisstreet, 1993; Kou- laidis & Christidou, 1999; Rye, Rubba & Wiesenmayer, 1997).

However, in some areas there was a very significant increase in students’ understanding of key concepts related to global warming after the teaching intervention and this was supported by the interview data. For example, when asked if there was no Greenhouse Effect would there still be humans and other animals on earth, some responses included:

David: No, because we need some Greenhouse gases to live, to keep warm.

William: No, ‘cause the Greenhouse Effect actually warms up the planet and if we don’t have it there wouldn’t be any warmth.

In the post-test, 71.5% of students correctly identified that people and other animals need the Greenhouse Effect and 58% agreed that the Greenhouse Effect was a partly natural occurrence. Both of these items displayed improvements in correct answers by 34% and 10% respectively, indicating that teaching about the natural Greenhouse Effect had been effective, perhaps because this concept had been given particular attention during the teaching intervention.

Student views about the intervention unit

It was important to determine what aspects of the teaching intervention students had found most effective, so the interviews included some specific questions about the pedagogy. In general the students found the hands-on activities to be the most enjoyable and informative. For example, when Jason was asked to identify an aspect of the teaching unit that helped him to learn something new he replied:

Jason: I liked the ... and I learned a bit more from the one where people made the little houses and put them in the light. (Jason is referring to an experiment that illustrated the effectiveness of orientation and insulation in energy efficient building design.)

When he was asked to identify a part of the unit that improved his understanding, Tom referred to the activity designed to teach about the issue of rising sea levels:

Tom: Yeah, about the ice cube in the water.

Interviewer: So did that experiment help to improve your understanding about sea levels?

Tom: Yeah.

Gary also made reference to this experiment:

Interviewer: So, thinking back to the unit last term, were there some things that you didn’t know or didn’t understand before the unit that you understand better now?

Gary: A lot of things.

Interviewer: Like what? Can you give me an example?

Gary: Well, the Artic. I never knew that. I never knew about the North Pole.

I thought it was actually on land ... [and] I never knew they had so many types of electricity (ways to generate it).

Interviewer: OK. So you remember the day we looked at all the different ways of making electricity and also the experiment about sea levels helped you to understand that one?

Gary: Yep.

Ben could also link a specific activity to a learning experience:

Ben: I now understand the difference between the ozone layer and the Greenhouse gas layer.

Interviewer: Ok, so can you think of an activity that really helped you to understand that better?

Ben: I think it was the activity when you showed us the pictures of the globe and you showed us how the ozone layer worked and how the Greenhouse gas layer worked.

It appeared that certain activities had an impact on the children’s understanding of particular concepts. Certainly their responses suggest that providing carefully selected concrete, hands-on learning experiences related to global warming may well improve understanding of this concept.

Personal influence and concern levels

The survey and interviews also attempted to determine students’ environmental attitudes and behaviours and what might engender change in these areas. It is important to acknowledge that children of 11 or 12 years old are unlikely to have the same options for their environmental behaviours as adults do, and whilst they may have an influence over some family spending choices and habits such as recycling, their influence is likely to be limited and highly dependent upon the beliefs of their family. Furthermore, as Devine-Wright et al (2004) suggest, the attitudes children hold about environmental issues are likely to be heavily dependent upon their family background.

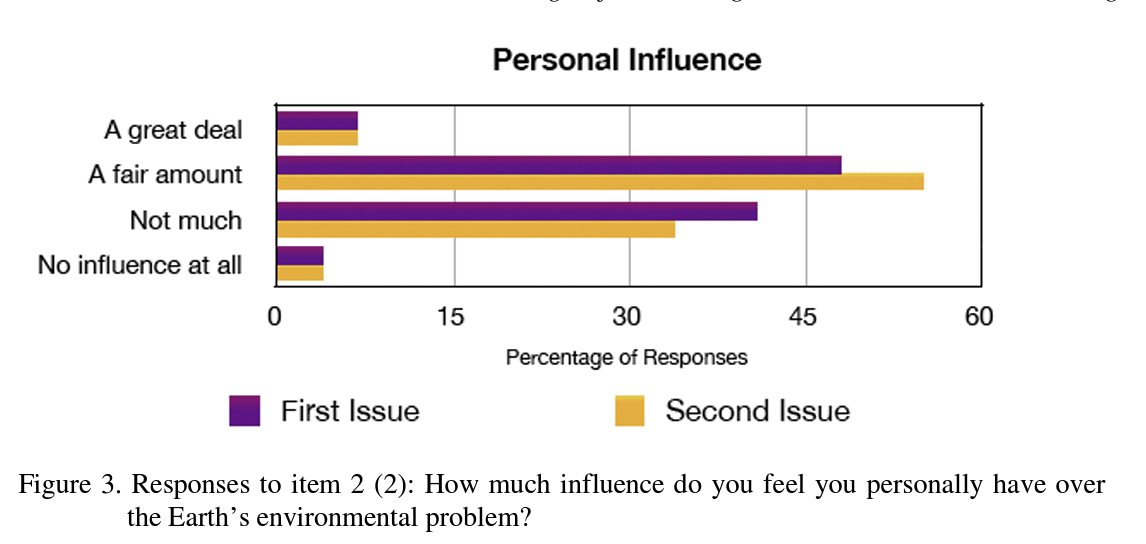

The issue of a child’s beliefs about their level of personal influence on the environment was addressed in the survey in item 2 (2): How much influence do you feel you personally have over the Earth’s environmental problem? Figure 3 provides data from the first and second responses.

The responses to this item showed limited change overall. However, some students did move from ‘not much’ to ‘a fair amount’.

Ben is an example of one such student who indicated an improved sense of empowerment, changing from ‘not much’ to ‘a fair amount’. When questioned about this change in the interview he explained:

Cause you taught me that I can have a bit of influence over some people, like my parents. Ben went on to say that his family was now changing some of their environmental behaviours, at his suggestion.

Some children who indicated an increased belief in their influence levels were able support their claim by listing actions they could take. Amy pointed out that she could:

Not use electricity that much and turn the lights off when you’re not using them and buy refrigerators that don’t use much electricity ... and don’t take long showers.

Hannah said:

Turn off the lights. Buy products with low energy use. I can turn off my things at the power point. We’re thinking about getting solar power now. Make sure I have a full load in the washing machine.

However, as Stern (2000) points out, an environmentally friendly attitude does not necessarily translate into environmentally friendly behaviour. Although children could identify actions they could take, there was no way of verifying if the actions were actually taken.

The issue of concern about global warming indicated an increase the second administration of the survey with 73% of students indicating that their concern levels were either ‘concerned’ or ‘very concerned’ compared to 47% in the first administration (see Figure 4). These figures are similar to the findings of Skamp, Boyes and Stanisstreet (2007) who reported that in their once-off survey, 58% of their participants indicated that they were either ‘quite worried’ or ‘very worried’.

When questioned about concern levels in the interview some children made a direct link between an increased level of concern and increased knowledge of the issue. William’s concern levels increased from ‘concerned’ to ‘very concerned’, an increase he explained by saying:

You just explained a whole lot more (about) how the earth warms up and all that stuff.

However, rather than letting his increased concern turn to feelings of helplessness, William added a comment which indicates his hopes for the future of this issue:

I also think you can stop and reduce the Greenhouse Effect a person makes...

Yasmin’s concern levels were identical to William’s, increasing in the second administration of the survey. When asked to explain this increase she responded:

Because when we visited that house (an ecofriendly house) you told me lots of the things about global warming and stuff so then I was a bit more concerned about it.

Interviewer: So you think that knowing more about it made you a bit more concerned?

Yeah.

In an attempt to address heightened concerns and provide the students with a sense of action competence, one specific teaching strategy employed. This involved concluding each of the eight lessons taught during the unit on a positive note. The students created a class poster that listed steps that they could take to help the environment. Each week a new step was discussed and added to the poster at the end of the lesson (Figure 5). However, the findings of this study confirm that informing students about environmental issues while also attempting to allay their concerns is a very challenging problem for teachers and other environmental educators.

Conclusions

Although the quantitative results form the pre and post-test comparison did not show a dramatic improvement in knowledge, they were pleasing given the short period over which the teaching intervention took place and the level of complexity of some of the concepts associated with global warming. This suggests that there is a place for teaching this subject explicitly towards the end of primary schooling. It would be interesting to see if a longer intervention resulted in greater improvement in knowledge. Improving knowledge about environmental issues and problems is important, particularly at an early age, because as Boyes and Stanis- street (1993) it allows individuals to make more informed decisions about things that impact upon the environment such as energy consumption.

The quantitative research revealed a number of misconceptions that proved very difficult to change. For example over one-third of respondents believed that the Greenhouse Effect was visible from space and nearly two-thirds of the cohort continued to attempt to make a link between polluted rivers and the Greenhouse Effect. This is perhaps not surprising as the literature on science education cites many examples of how once established, misconceptions are highly resistant even in the face of quite persuasive teaching (see e.g. Hewson, 1981). These authors point out that even when the existing conception is addressed and new information systematically introduced, the learner may still chose to remain with their initial conception. With highly resistant misconceptions, a period longer than one school term and more targeted activities may be required to produce conceptual or partial conceptual change.

However, there were some misconceptions that appeared to be effectively addressed by the teaching intervention. There was a strong improvement on the issue of the cause of rising

sea levels, with children being able to identify which activities contributed to the problem and which did not. Students were also able to identify that the Greenhouse Effect was partly natural and essential to life on earth. This was perhaps because the teaching activities designed to address these were particularly effective. The evidence provided by the qualitative data tended to support this as most of the children interviewed could not only answer these questions correctly but could justify their answer.

The qualitative data gathered from the interviews highlighted the tendency for some children to group all environmental issues as one, thus confusing aspects such as air and water pollution with global warming. This is similar to findings from other researchers such as Fortner (2001) and Summers et al (2001) that found that children often had difficulty discriminating between the causes and effects of various environmental issues.

One of the most informative aspects of the data was when the students were able to identify an element of the unit that helped them to a better understanding of global warming. Almost all participants nominated an aspect that involved a class experiment or a visual aid. The benefit of hands-on experiences in environmental education is nothing new, but this study reinforced it further.

This study was also concerned with the ‘worry factor’ that children identified and it appeared that while more children felt they could have a positive influence over global warming by the conclusion of the study, participants also stated that increased awareness had resulted in increased concern. However, this need not be viewed as a negative. Increased concern, when tempered with good knowledge levels and a belief that change is possible, may lead to high levels of motivation. Jensen and Schnack (1997) argue that even before teaching intervention children may already be worried, so explicit teaching about this issue may actually bring these concerns out into the open where they can be dealt with constructively. Furthermore, teaching environmental education with an action component as recommended by Jensen (2002), can help give students a sense of empowerment and reduce feelings of paralysis, but this often requires a supportive school community, a suitable project and sufficient time for students to see the results of their work. Similarly, attitude is likely to be highly influenced by factors such as peers, media and family. Any change in attitude or behaviour was self-reported and unsubstantiated and as such, must remain an indication only. However, it can be argued that an increased understanding about the issue of global warming can allow children to make more informed choices, especially within the ever growing field of ‘green consumerism’. Even at the age of 11 or 12, children are consumers and as Strong (1998) discovered, they hold considerable influence over what their parents purchase. It is possible that the knowledge gained during this study may allow children to participate constructively in decisions that may affect their families’ ecological footprint.

References

- Boyes, E., & Stanisstreet, M. (1993). The “Greenhouse Effect”: Children’s perceptions of causes, consequences and cures. International Journal of Science Education, 75(5), 531-552.

- Connell, S., Fieri, J., Lee, J., Sykes, H., & Yenken, D. (1999). If it doesn't directly affect you, you don't think about it: A qualitative study of young people's environmental attitudes in two Australian cities. Environmental Education Research, 5(1), 95-113.

- Coe, R. (2002). It's the effect size, stupid: What effect size is and why it is important. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Educational Research Association, University of Exeter, England, 12-14 September.

- Department of Environment and Heritage. (2005). Educating for a Sustainable Future: A National Environmental Education Statement for Australian Schools. Carlton South: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Devine-Wright, P., Devine-Wright, H., & Fleming, P. (2004). Situational influences upon children’s beliefs about global warming and energy. Environmental Education Research, 70(4), 493-506.

- Fisher, B. (1998). Australia student's appreciation of the greenhouse effect and the ozone hole. Australian Science Teachers Journal, 44(3), 46-55.

- Fortner, R. (2001). Climate change in school: Where does it fit and how ready are we? Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 9(2), 82-98.

- Hewson, P. (1981). A conceptual change approach to learning science. International Journal of Science Education, 3(4), 383-396.

- Jensen, B., & Schnack, К. (1997). The action competence approach in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 3(2), 163-178.

- Jensen, B. (2002). Knowledge, action and pro-environmental behaviour. Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 325-334.

- Kefford, R. F. (2006). Medical heat for climate change. The Medical Journal of Australia, 784(11), 582.

- Koulaidis, V., & Christidou, V. (1999). Models of students’ thinking concerning the greenhouse effect and teaching implications. Science Education, 83(5), 559-576.

- MacMullin, C. (2007). Children say what they worry about: Behind the news survey report. Retrieved December 12,2007, from http ://www. ens.gu. edu.au/ ciree/LSE/MOD8 .HIM

- McInerney, D., & McInerney, V. (2002). Educational psychology: Constructing learning. Frenchs Forest: Prentice Hall.

- Nicholson-Cole, S. A. (2005). Representing climate change futures: a critique on the use of images for visual communication. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 29(3), 255-273.

- Osborne, R., & Cosgrove M. (1983). Children’s conceptions of the changes of state of water. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 20(9), 825-838.

- Rye, J. A., Rubba, P. A., & Wiesenmayer, R. L. (1997). An investigation of middle school students’ alternative conceptions of global warming. International Journal of Science Education, 79(5), 527-551.

- Skamp, K., Boyes, E., & Stanisstreet, M. (2007, July). Global warming: Do students become more willing to be environmentally friendly as they get older? Paper presented at the Australasian Science Education Research Association Conference, Perth.

- Stem, P. (2000). Towards a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407-424.

- Strong, C. (1998). The impact of environmental education on children’s knowledge and awareness of environmental concerns. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 76(6), 349-355.

- Summers, M., Kruger, C., Childs, A., & Mant, J. (2001). Understanding the science of environmental issues: development of a subject knowledge guide for primary teacher education. International Journal of Science Education, 23(1), 33-53.